Maurizio Cattelan: Hi Maurizio. We haven’t been in contact since Christmas. Do you still collect objects? It seems like your house is a sort of total work of art, a house-studio-museum filled with objects. How do you choose the things you collect? Do you come across them by chance or do you have criteria that urge you to keep certain pieces rather than others?

Maurizio Mercuri: Like Linus’s blanket, objects give a sense of security, they reassure me. Transitional objects give comfort; they are three-dimensional ideas, an extension of intelligence.

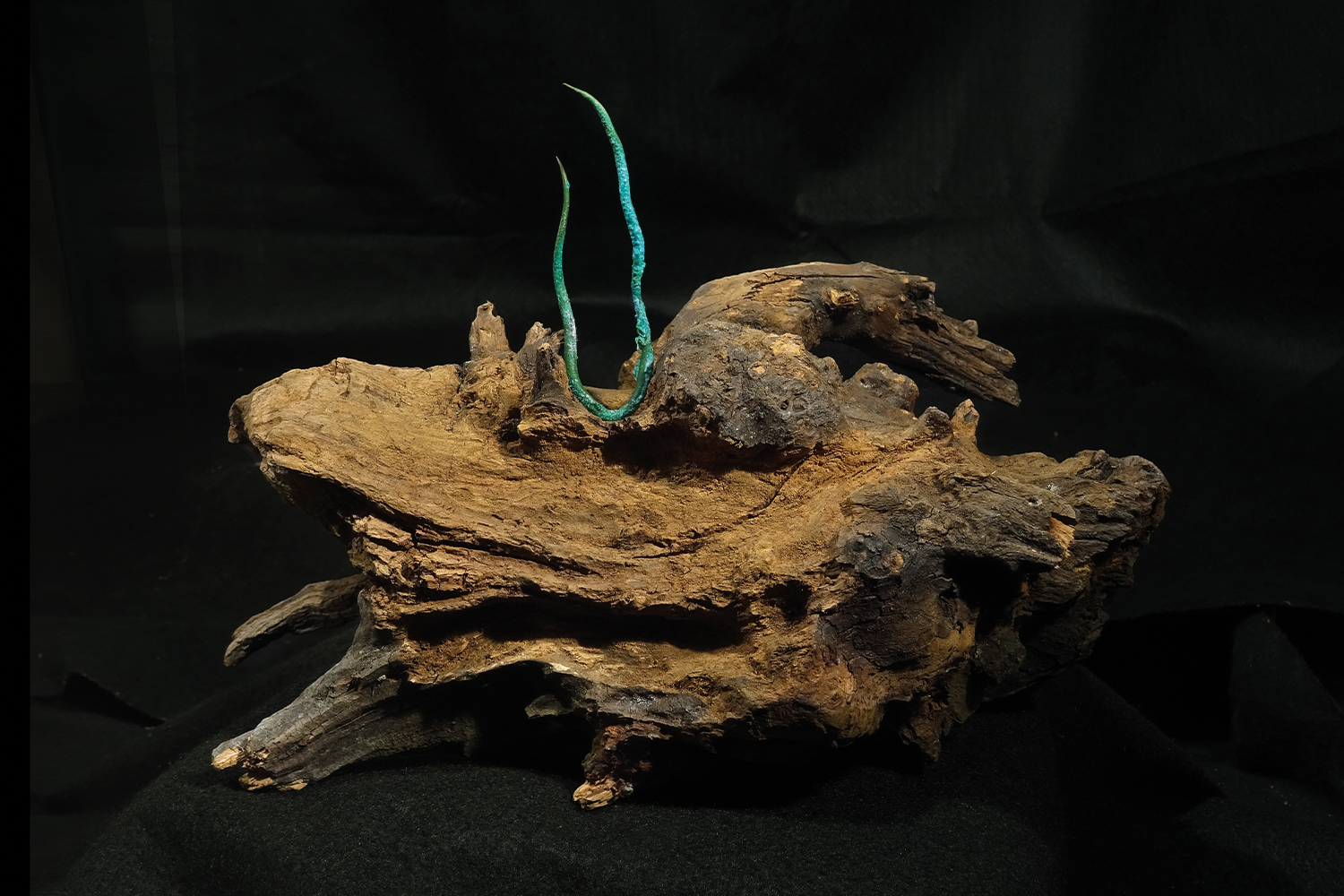

I began collecting natural things, then I added obsolete technological items, various instruments. Sometimes I’m fascinated by kitsch.

Once I didn’t have a camera, so I started collecting pieces that would give me the feeling of owning an image or a memory.

When the stacks of objects reach a critical mass, I find things that I no longer knew I had.

If you look at Jean-François Millet’s painting The Gleaners, you understand that what we always collect is ourselves.

MC: In your opinion, what is the difference between collecting and turning an object into a work of art?

MM: For me, collecting represents the creation of a stock where I can go and get what I need. I like the idea of cataloging.

When I look at a meadow I want to know the names of all the different species of grasses, and when I look at the night sky, I want to know the names of all the stars. I am interested in structure and taxonomy, and my work starts from this approach: “culture and society” is exactly that.

As for turning bits of reality into works of art, there are different ways to do it, such as changing a context: in Palermo, for Manifesta 12, I put a person on a diet for the duration of the exhibition.

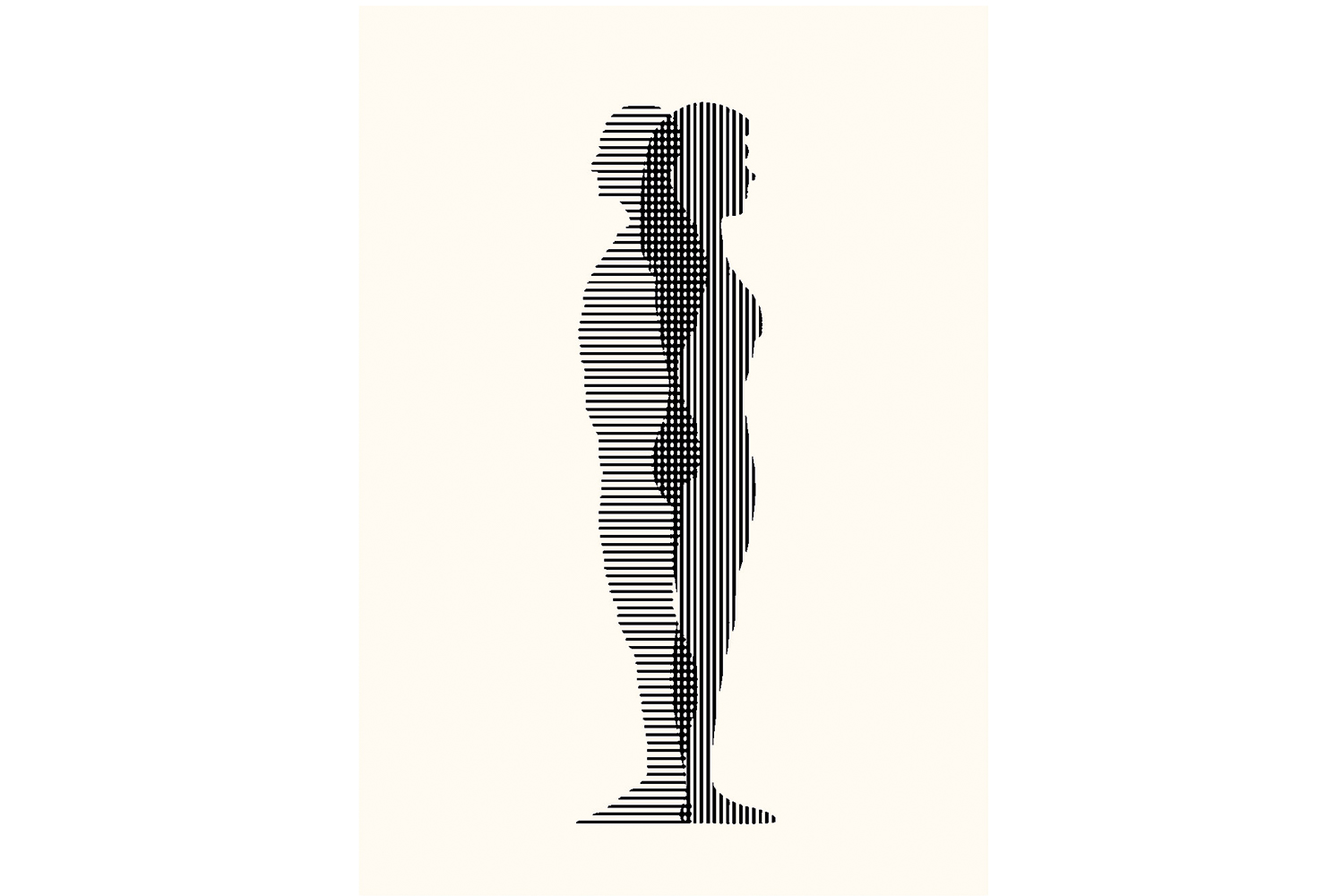

MC: Keeping your distance, moving around the fringes, staying in the shadows, hiding, not seeing… These are behaviors that are often apparent in your works or in the images you use in them. Do you like to disappear too? How do these attitudes relate to your daily reality?

MM: In fact, I am just like that, and it’s my works that travel around instead of me. I prefer to move discreetly and stay on the edge, sometimes hiding, so I have a better view of what’s happening and can keep a certain distance without being conditioned by it.

MC: You currently live in San Donato in the Marche region, a hamlet in the municipality of Fabriano, in Central Italy. This is a radical and unusual choice for an artist: is this a philosophy of life, a necessity, or simply the result of chance?

MM: “Home is where the heart is,” said Pliny the Elder. I spent ten or so years traveling and now I am metabolizing what I saw and felt. Every day is a surprise: “No day without a line drawn.”

MC: I also heard that you have a breathtaking view. Is this aspect important to you?

MM: When the air is clear, I can see the Sibylline Mountains, and for me it’s already a great day.

On the subject of the horizon, I had a dream: the sea level had risen to flood the valley at the foot of my hill, and this made me happy because I had the sea nearby.

MC: How would you define the relationship between the remoteness of where you live and work and the city? Do you feel there is some kind of magnetic opposition between the two?

MM: I like to work remotely. It’s like doing magic. I love the idea of connecting with what’s going on in another place when just a few moments before I was hoeing the garden. In this way, my time and rhythms are not compromised.

Those who work with me receive things that come from a place that is almost exotic. Don’t forget that the internet has shortened the distance between the center and the periphery.

I am interested in the psychological aspect of the city: one of my works consists of two cars side by side, one filled with curricula vitae, while in the other you can hear an audio track playing sounds of coughs.

MC: In an interview, you said that beneath beds and cars there is the abyss. What’s beneath your bed?

MM: Friends who greet me.

MC: Do you still build electronic devices and gadgets? For you, what is technology? A means to access the world or a tool to keep away from it?

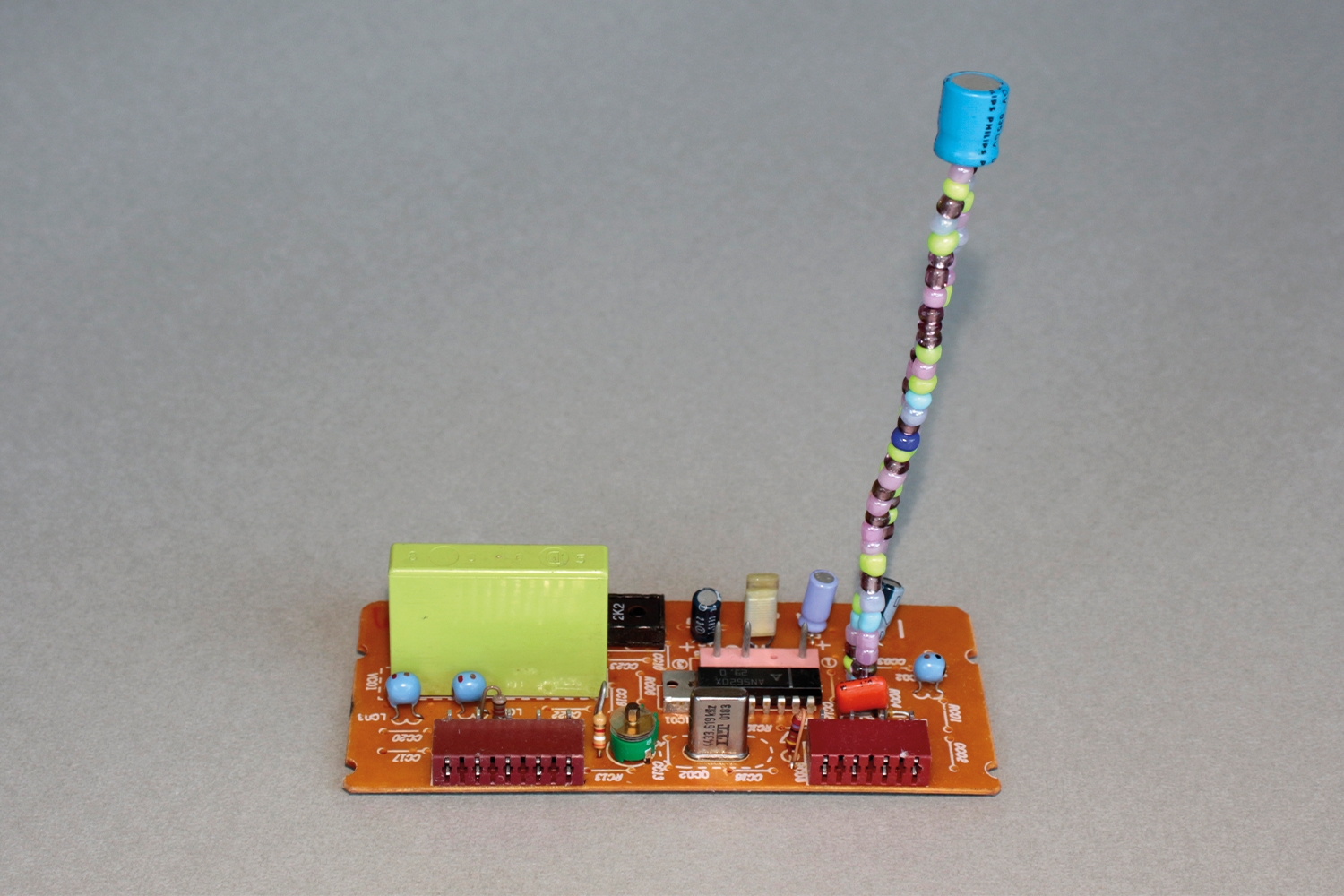

MM: I would say both: a way to access the world and a parallel reality where I can isolate myself, a dimension in which I feel like when I was a child and I used to play with construction toys.

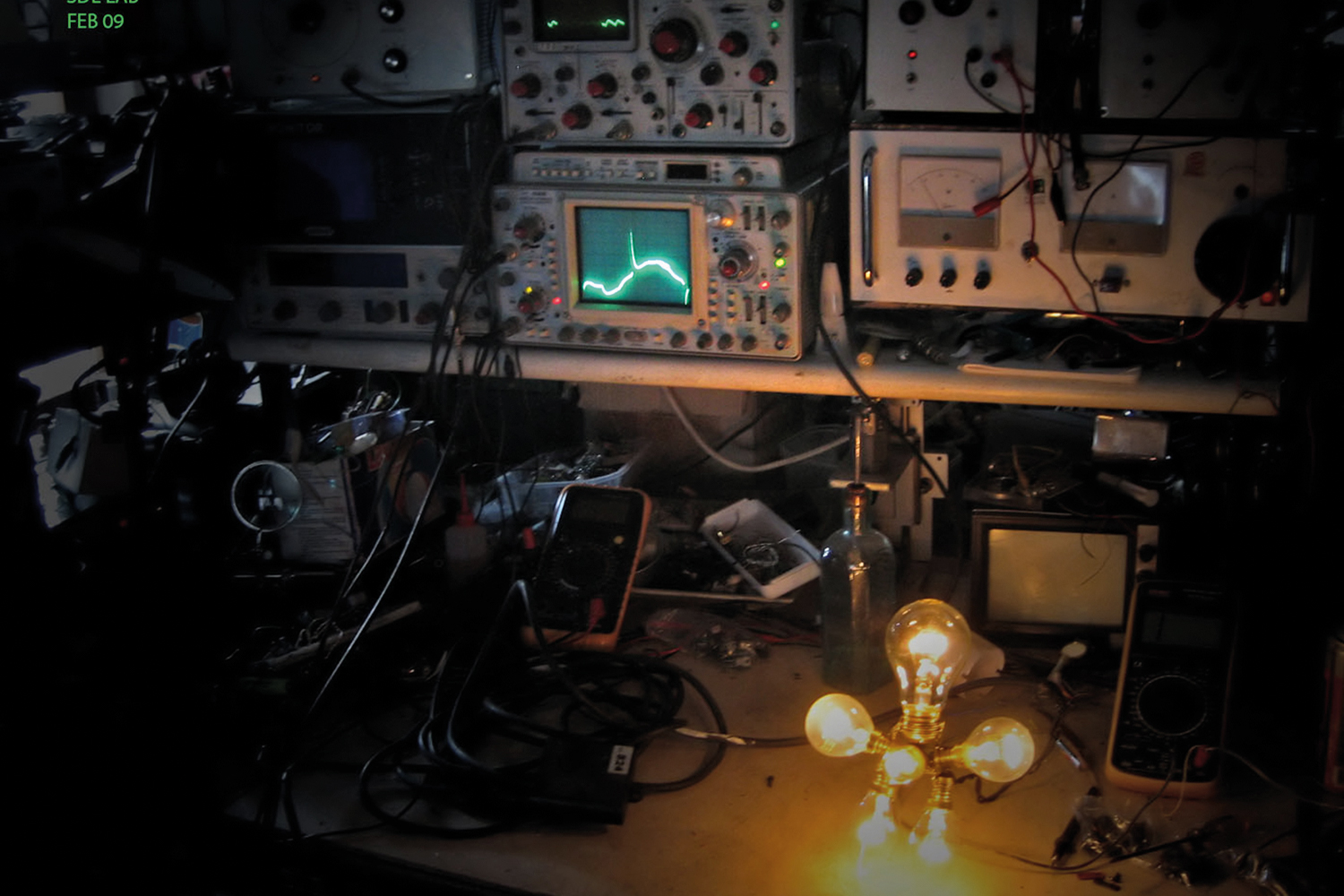

I am particularly interested in the aging process of technology: obsolete devices have a history and a reference imagery. All this drives my inspiration to develop devices that operate lights or mechanisms able to move video cameras.

But I also love pure electronics, circuits that generate spectra and waveforms without any practical application.

MC: How does this fascination with technology exist alongside a lifestyle that embraces the nature on your doorstep?

MM: A biologist friend of mine told me that nature is a technology that is millions of years old.

MC: What do you mean by “reverse engineering”?

MM: It means taking something to pieces so you can understand how it is made.

But for me it is as if there was a secret inside it, something to figure out, an unknown alphabet that needs to be interpreted.

Once again, this goes back to my childhood, when I took apart toys I received as presents.

MC: Technologies have irreparably altered the rhythms of nature. Why do you think it is still important to take an approach that harmonizes with the natural world?

MM: The first technology that altered our rhythms from those of nature is Stonehenge, a solar calendar.

Our rhythms have evolved profoundly since ancient times, whereas the rhythms of nature have only recently changed as a result of the Industrial Revolution.

Returning to man’s rhythms, we have always felt a need to regulate time. During the Ming dynasty, Matteo Ricci, who like me was from the Marche, gained prestige at the Chinese emperor’s court after displaying a mechanical clock. With the evolution of technology, from Stonehenge to electronics, the way we relate to nature and the passage of time kept on changing.

MC: Last year at the Guggenheim in New York, Rem Koolhaas presented the project “Countryside, The Future,” which urged a return to life in the countryside. You’ve been doing it for years. Do you feel you’re ahead of the times? Or was Koolhaas copying you?

MM: I live in the countryside but I take computers apart. After all, the phenomenon of electricity is both natural and artificial. The word electricity comes from electron, a Greek word that means amber, a natural resin.

But, going back to Koolhaas, it is the architecture of Wright’s Guggenheim that creates a contact with nature.

MC: A few years ago, in an interview you said: “The redemption of an object is the artist’s responsibility, not only as a generator of meaning, but above all as a holder of power.” How does the artist become a holder of power?

MM: I say a lot of things, but also their opposite.

MC: The title of a work is often the key to a possible meaning. With I Lost Time what are you referring to?

MM: The titles of my works are not didactic. They are detached from any meaning: they lead to other paths, which in turn lead to more paths, that finally get lost.

MC: Do you have any suggestions for young artists today?

MM: Be mentally erratic.

MC: Do you think the meaning of a work of art has changed?

MM: The meaning of art is based on the relationship with its surroundings, and the context is constantly evolving. Let me explain with an extreme example: the imprint of a painted hand on a rock could have had a meaning for the primitive man that today we can only try to imagine.

MC: They say that in life there are trains that pass only once: in your career as an artist, do you think that sometimes letting supposed “opportunities” pass by is actually a way to “take that train”?

MM: More than with travelers, I feel in tune with trees, like the banana tree I portrayed myself with.

If you do have to travel, steer clear of crowded trains.