“The Uncanny Valley” is Flash Art’s new digital column offering a window on the developing field of artificial intelligence and its relationship to contemporary art.

The Internet has been envisioned as a technology with a radical form of agency, endowed with the capacity to make kids smarter (or dumber), to make social life more playful and fluid (or more sexually corrupt and deceitful), and to create an ideal “information society” where everyone is radically equal.1

Although social networking services (SNSs) purport to offer individuals more freedom and easier access to knowledge, they have produced a new apparatus of control over our identities and personalities. Their insertion between lines of communication has marketized self-esteem in a new, intuitive, and highly insidious fashion. Aaron Ben-Ze’ev has stressed the misguided perception that people can express themselves more freely online as anonymous, less liable, and less vulnerable agents.2 In reality, users crave the dopamine surge that accompanies notifications — texts, likes, and responses of all kinds. Adam Greenfield advises that “it changes us materially, rewiring neurotransmitter pathways, lighting up the rewards circuits of our brain, and enhancing the odds that we will trigger the whole cycle over again when the dopamine surge subsides in a few seconds.”3 The collapse of the old digital dualism that separated digital and physical realities has rendered users malleable according to a neoliberal logic of customer segmentation. John Cheney-Lippold identifies this as the logic of “algorithmic identity”:

[It is] an identity formation that works through mathematical algorithms to infer categories of identity on otherwise anonymous beings. It uses statistical commonality models to determine one’s gender, class, or race in an automatic manner at the same time as it defines the actual meaning of gender, class, or race themselves.4

SNSs collect data about humans, their race, age, activity, education, politics, and buying habits to allow companies to target us with more refined advertising, as well as to shape generic forms of algorithmic identity.5 It is hard not to feel that, armed with enough data, the mysteries of the human mind will eventually be decoded, producing a nightmarish dystopian future in which humans are fully controlled by AI systems. This essay looks to chart the prospects for resistance to our dataist nightmare by deepening awareness of algorithmic coercion as it is exerted by SNSs. It also questions whether the use of social networking sites for artistic subversion is enough to bring about substantive social and political change. Artists such as Hank Willis Thomas, Cauleen Smith, and Everest Pipkin have all wielded Instagram as a political tool, but where does one draw the line between radical activism and the aestheticization of identity politics?

Technologies expand human capabilities but are not necessarily good for democracy. Democracy will fail in unexpected ways. The looming dystopia to fear is a shell democracy run by smart machines and a new elite of progressive technocrats.6

AI technologies keep on failing humans by repeatedly showcasing racist and sexist behaviors. In 2019, a study published by the MIT Media Lab found that the facial recognition technology Rekognition performed worse when identifying an individual’s gender if they were Black or a woman. In tests led by Joy Buolamwini, Rekognition’s software better identified the gender of lighter-skinned men, but mistook nineteen percent of women and thirty-one percent of Black women for men.7 In 2018, machine-learning engineers at Amazon noticed that their internal candidate–screening system for job applicants was downgrading CVs that indicated the candidate was a woman.8 These instances represent a fraction of a much wider digital architecture of discrimination, one that extends to the stereotyping of video game avatars. For Lisa Nakamura, users don’t simply consume images of race anymore; they perform identities based on “constrained choices.” While for Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, the kind of racism that stems from faulty media representations must be confronted by offering more realistic portrayals of “raced others.”9 Platforms like Instagram complicate the cause of “realism,” with their algorithmic biases producing a saleable norm, witnessed in the so-called “Instagram face” that parallel apps such as Facetune and Celeb Face set out to achieve. This process of acculturating users to a dominant facial ideal defined by a narrow range of influencers manifests Sylvia Wynter’s “sociogenic principle” in digital form.10 Instagram thus limits the categories of acceptable humanity to those neoliberalism is designed to benefit.

Channeling Frantz Fanon, Simone Browne has recently addressed “epidermalization [as] a way of thinking [through] the ontological insecurity of the racial body as it experiences its ‘being through others.’”11 Her concept of “digital epidermalization” expresses the means whereby a raced body is converted into data as digitized code. The harvesting of biometric data as fuel for algorithmic operations turns contemporary surveillance into a mode of neocolonial oversight, one that demarcates online space according to ‘“ghettos” populated with lower-class, uneducated, potentially dangerous users of color” and spaces that are “safe, clean, and well supervised.”12 A number of hashtags representing political or activist movements have developed in recent years: #BLM, #Antifa, #MeToo. Online tribalism is defined as communities of people whose commonalities and beliefs often depend on connection via social media. Jamie Bartlett views this as problematic for democracy for the way small differences between us are transformed into unbridgeable gulfs.13 Using hashtags as vehicles for solidarity and resistance can empower the individual politically, but the condensing of community activism into homogenized datasets can also serve to marginalize that individual.

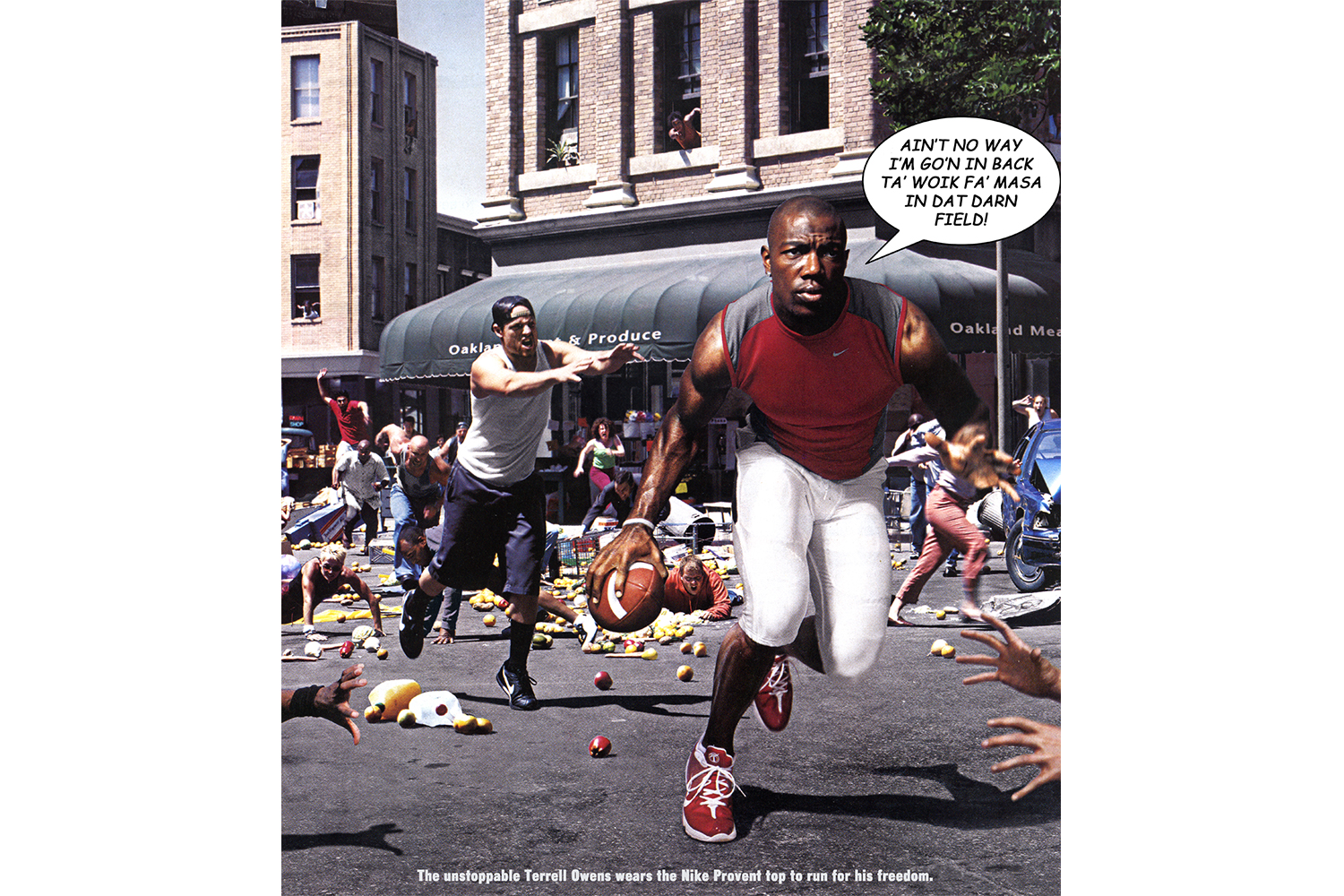

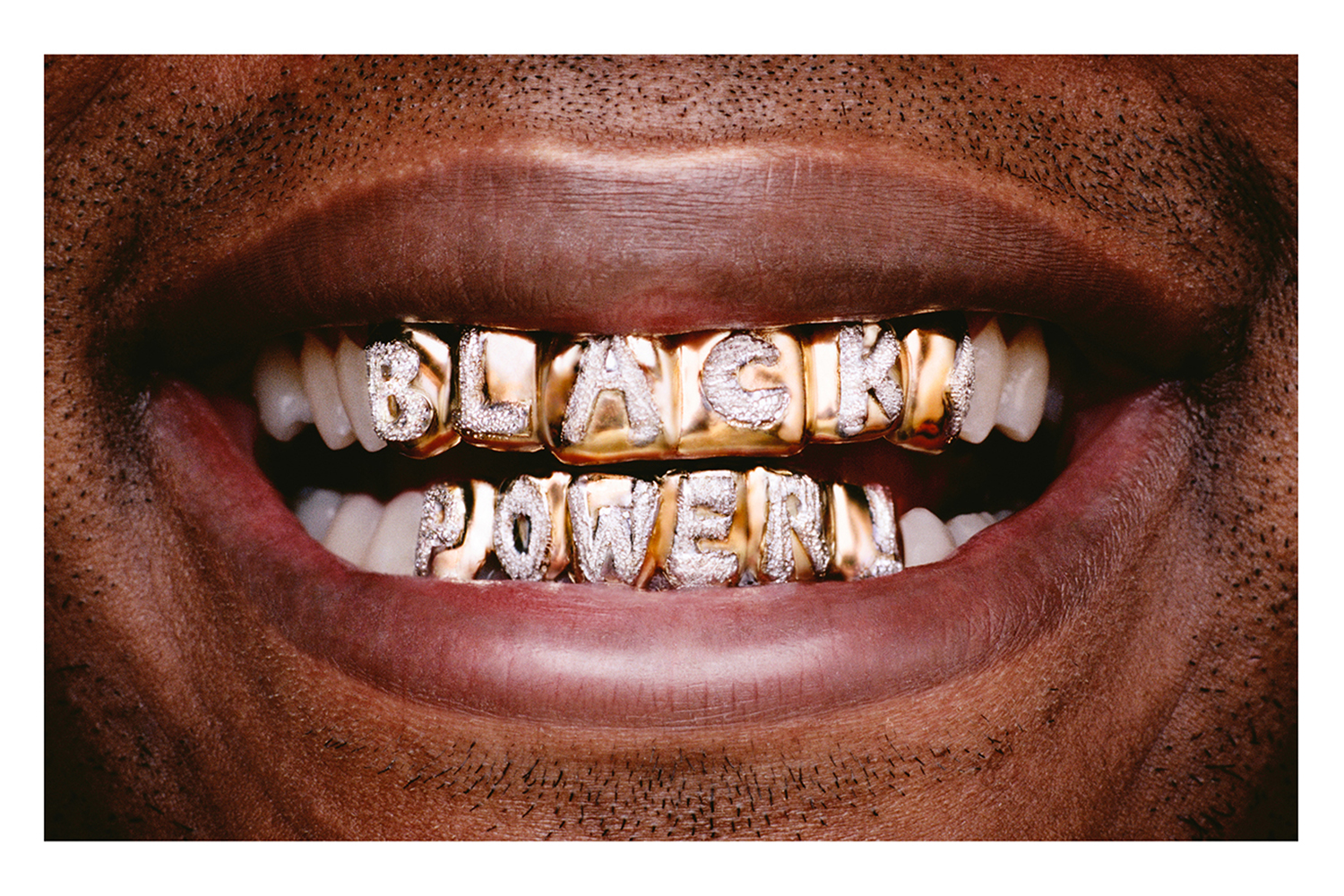

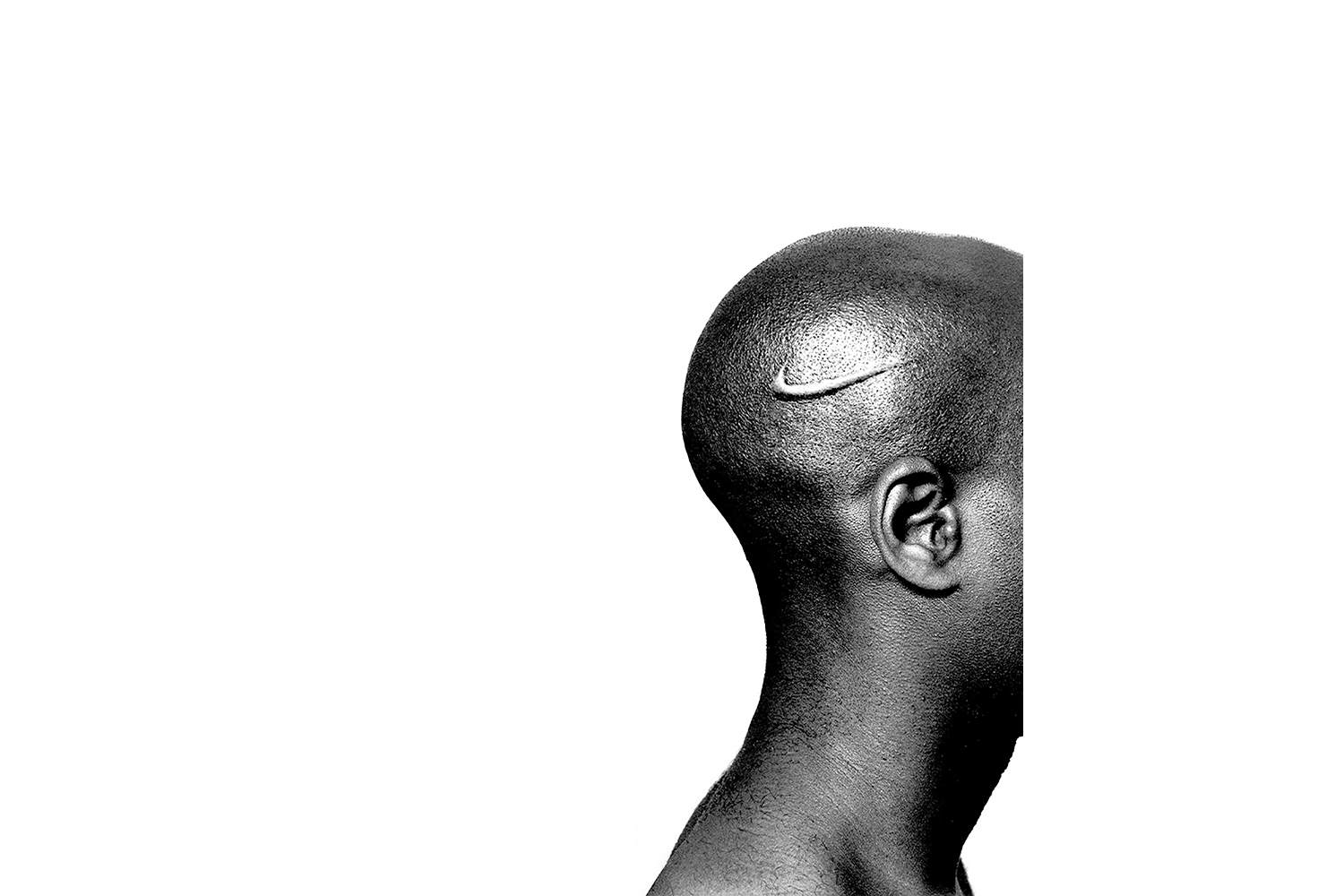

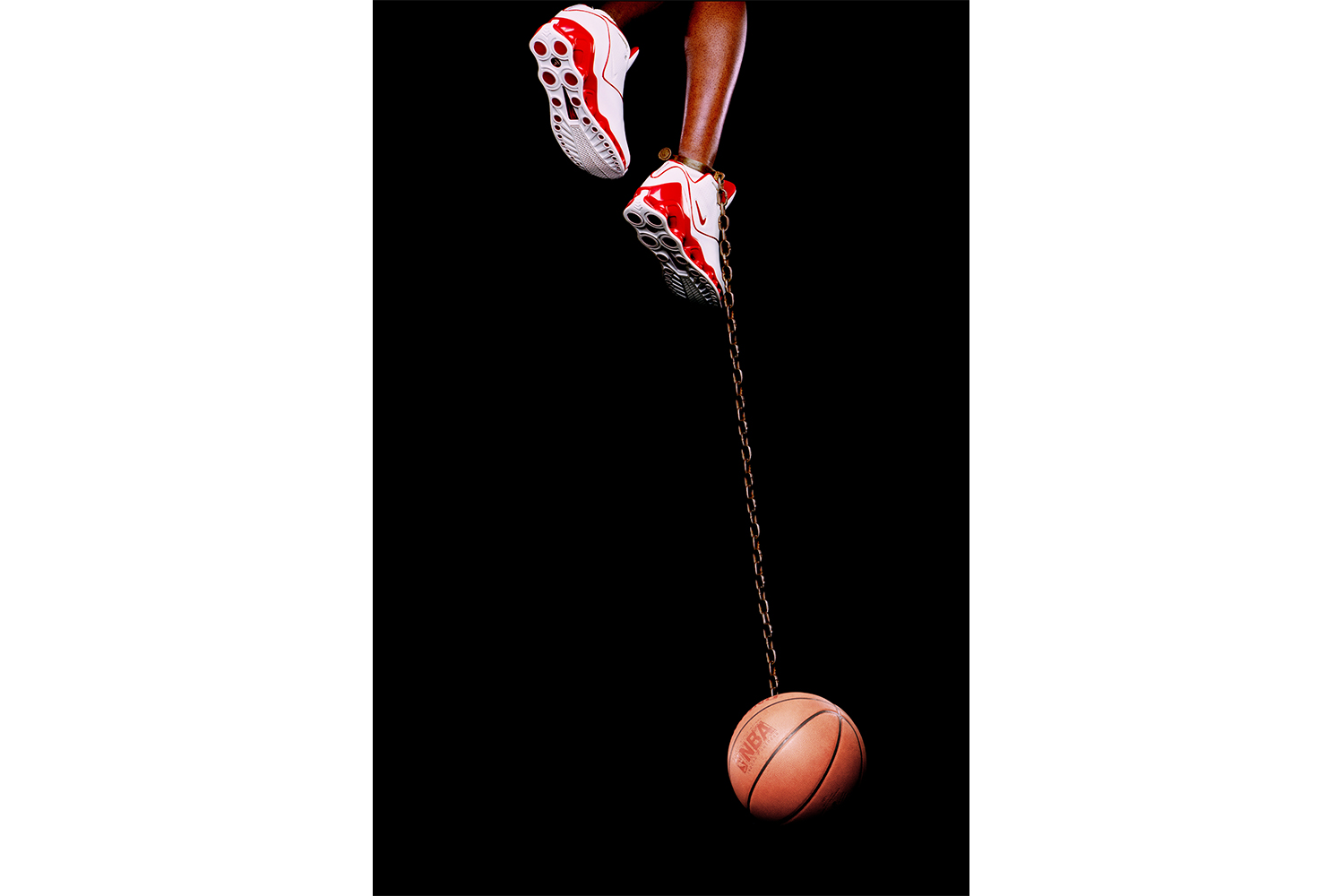

The work of Hank Willis Thomas focuses on how visual culture informs the way people perceive themselves and others, identifying as a “visual culture archaeologist.”14 Among Thomas’s many well-known political artworks is the photography series “Branded” (2006), which comments on how commercial branding exploits different communities. Comprising a group of images in which a scarred Nike logo was Photoshopped to the bodies of Black models, for Browne this work carries “the trauma of racial injury” — of wounding by commercial branding and of advertising’s power “to crop and frame the black body.”15 In Thomas’s work, branding becomes a metaphor for historic acts of epidermalization, whereby slaves imported from Africa were branded with a scar — usually a symbol burned into their skin — that sought to indicate permanent objecthood.

Thomas is also one of the founders of the For Freedoms collective, alongside Eric Gottesman, Michelle Woo, and Wyatt Gallery, that uses Instagram as a platform for sharing images of billboards located around the US, on which the artists display political messages. These works aim to reshape political discourse by widening the meaning and practices of democracy.16 As part of the campaign, more than seventy artists — from Ai Weiwei to the Guerilla Girls — have repurposed billboards in order to pose questions and post comments relating to social justice. This ongoing work inspires through its simplicity and, by extent, its accessibility. By sharing such powerful, political works on Instagram, the For Freedoms collective appropriates social media as a vehicle for critique, blurring the digital and the physical to do so.

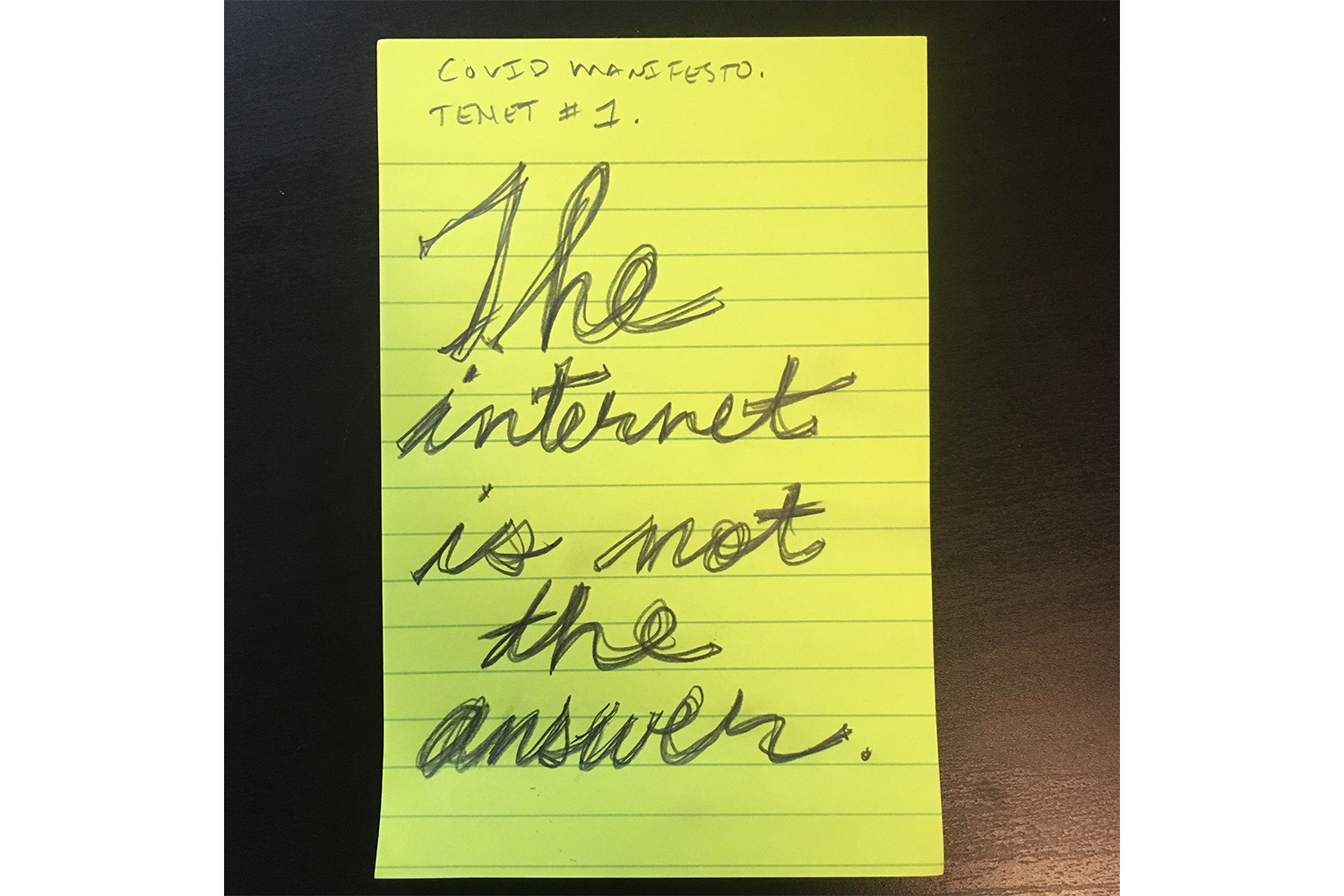

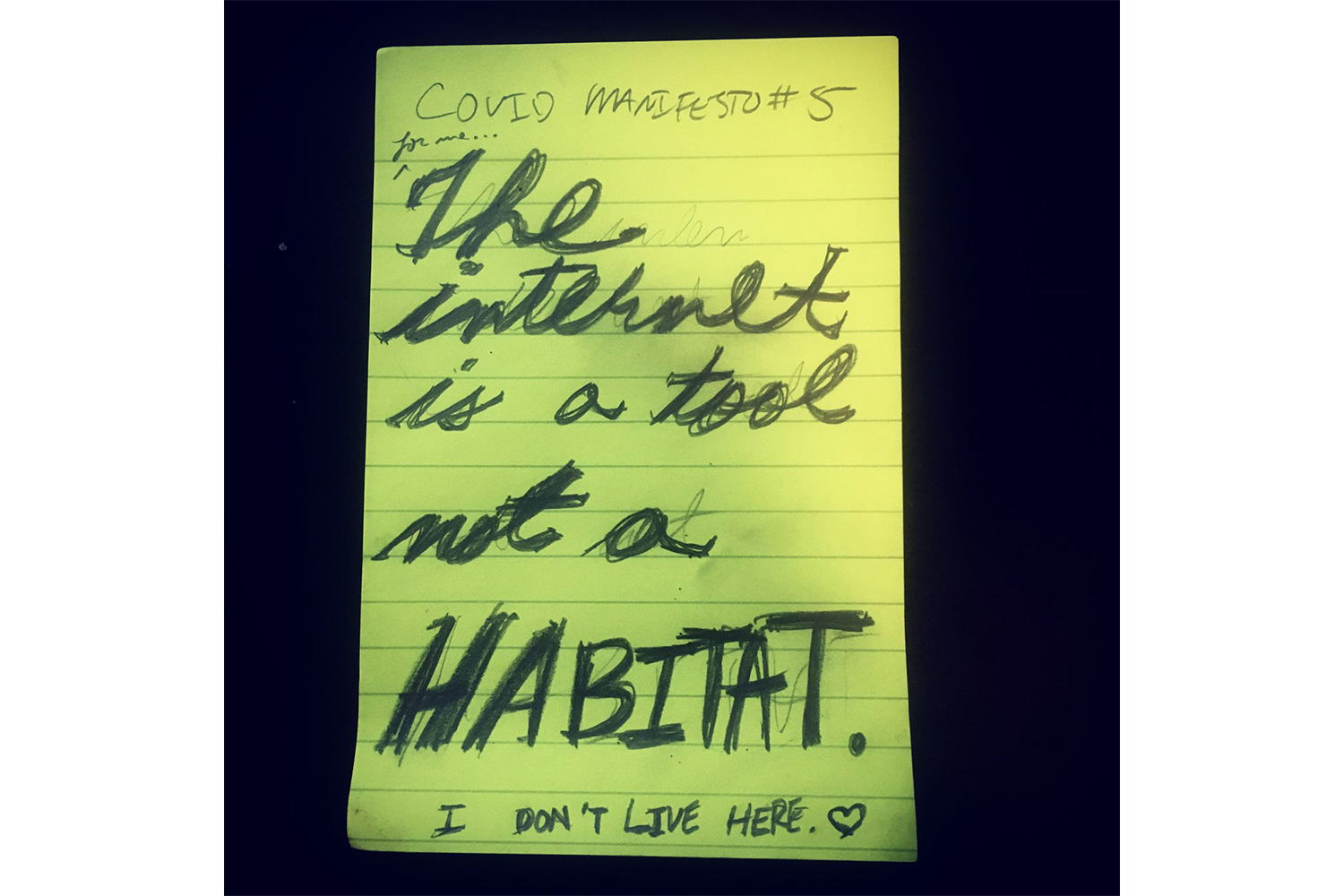

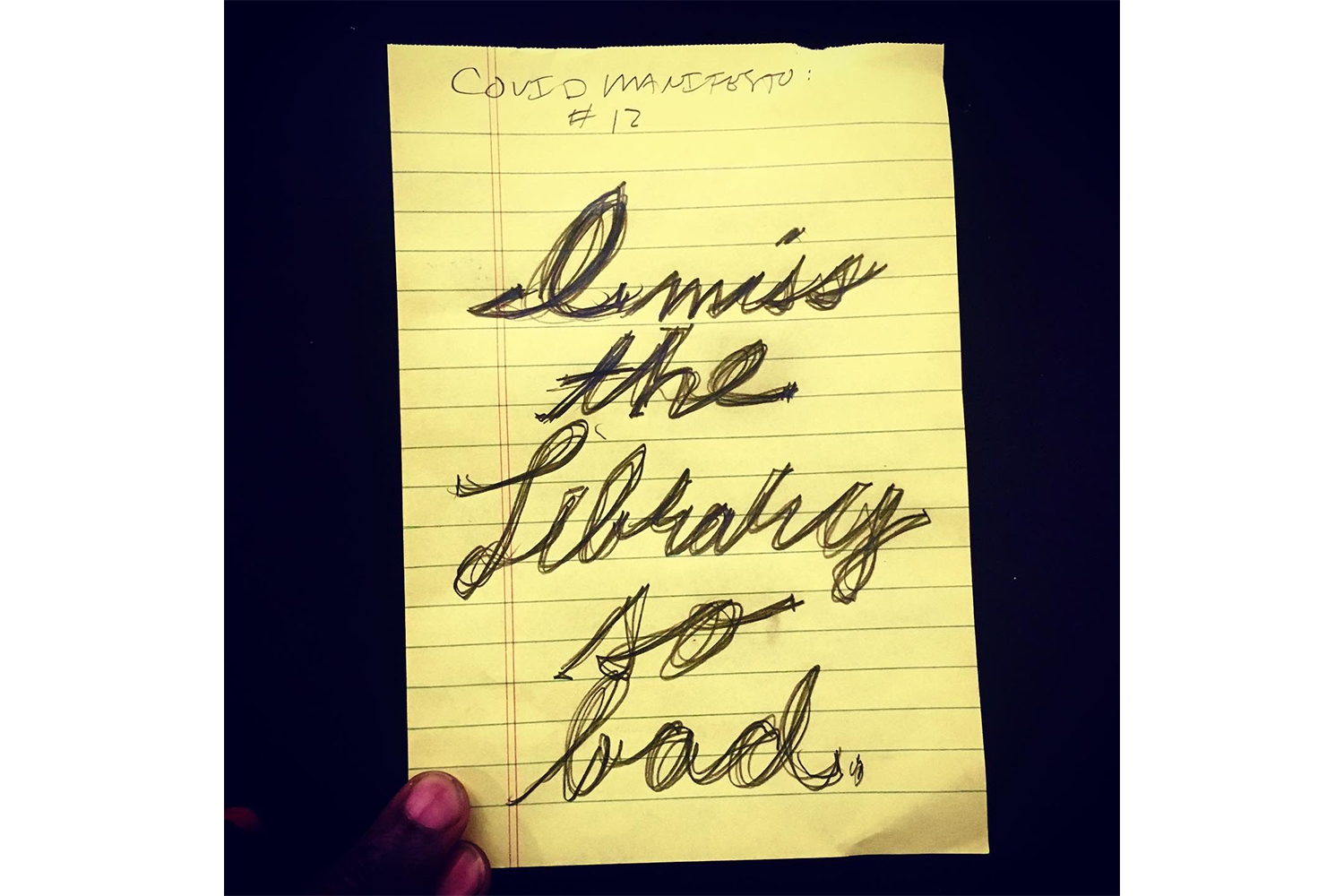

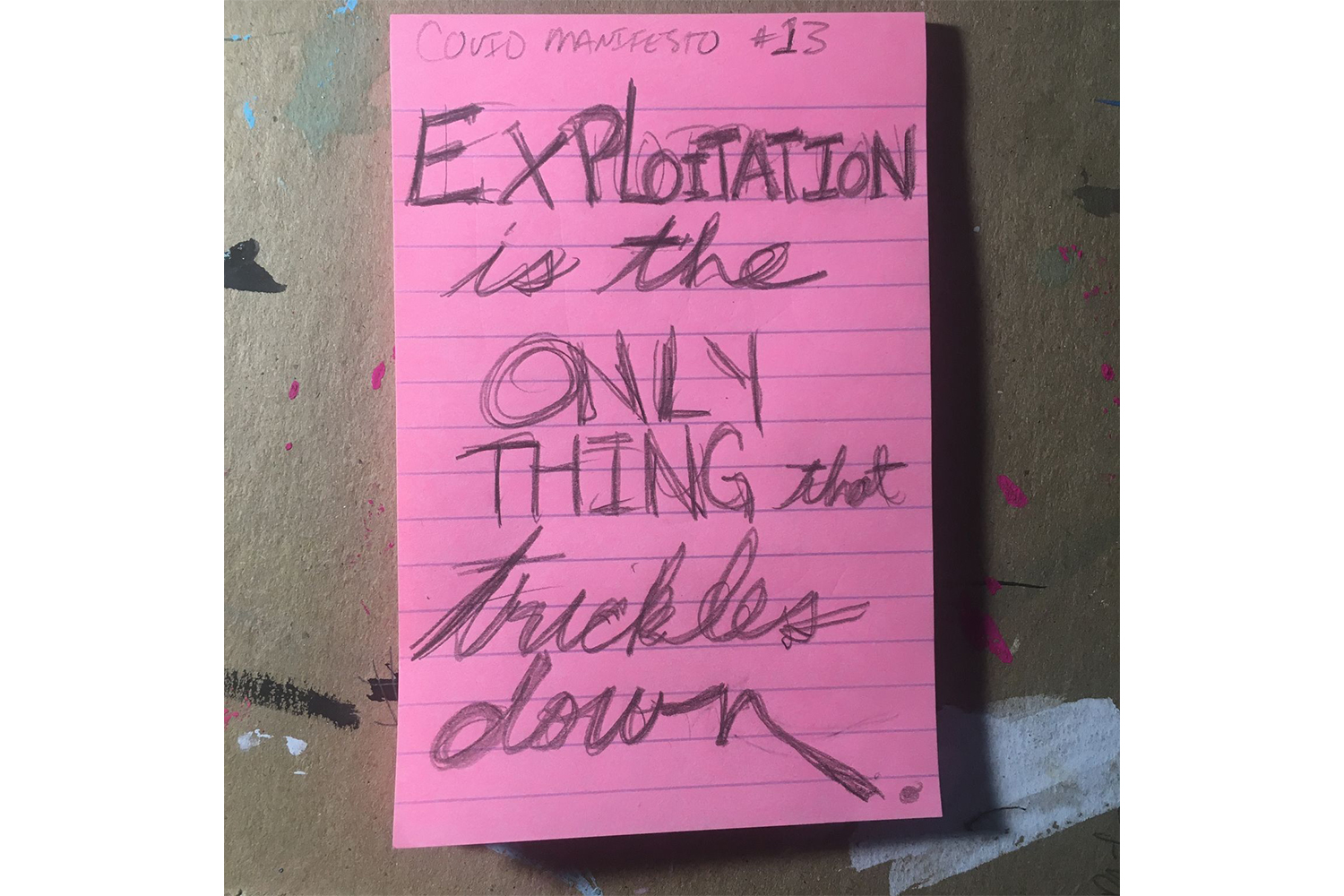

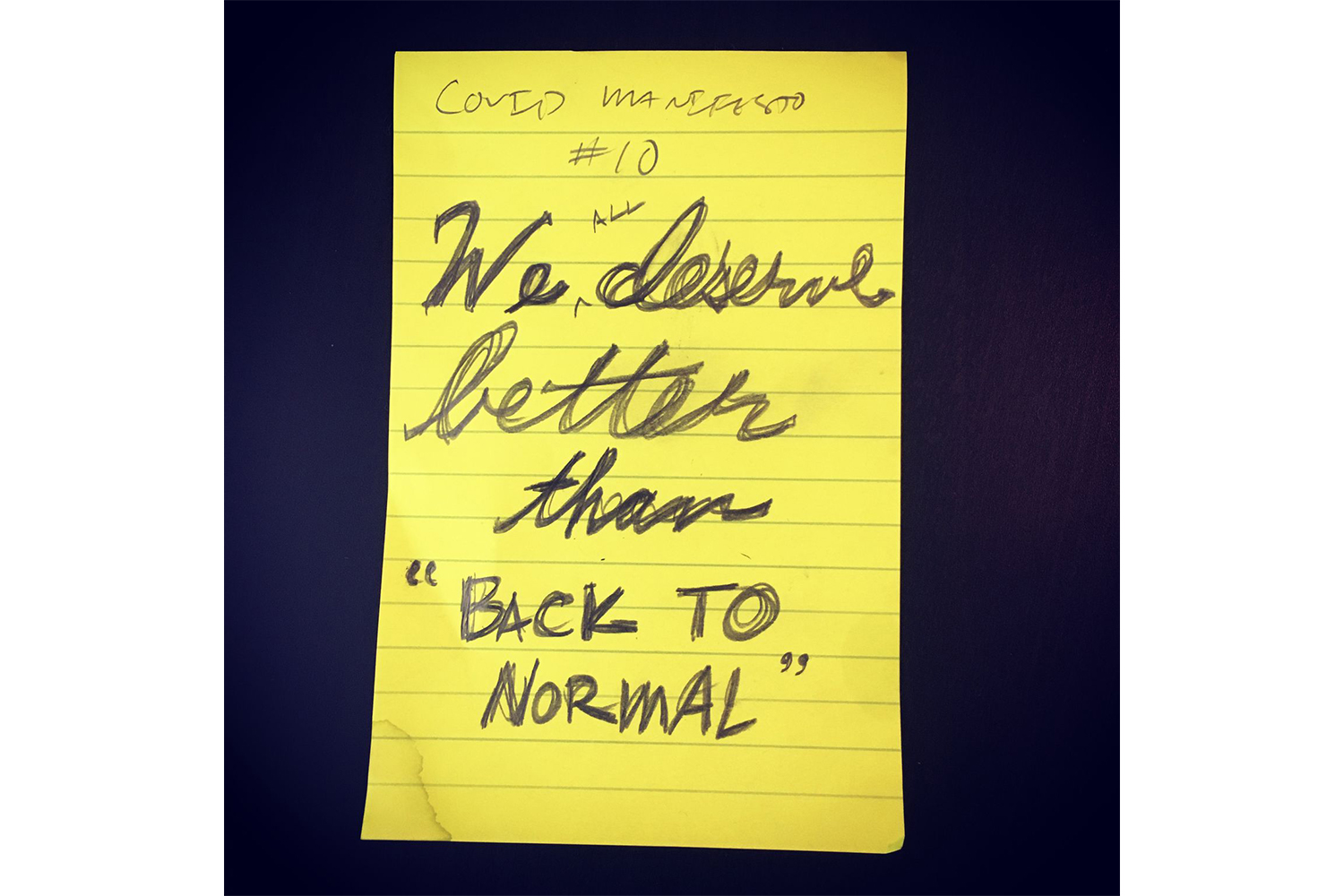

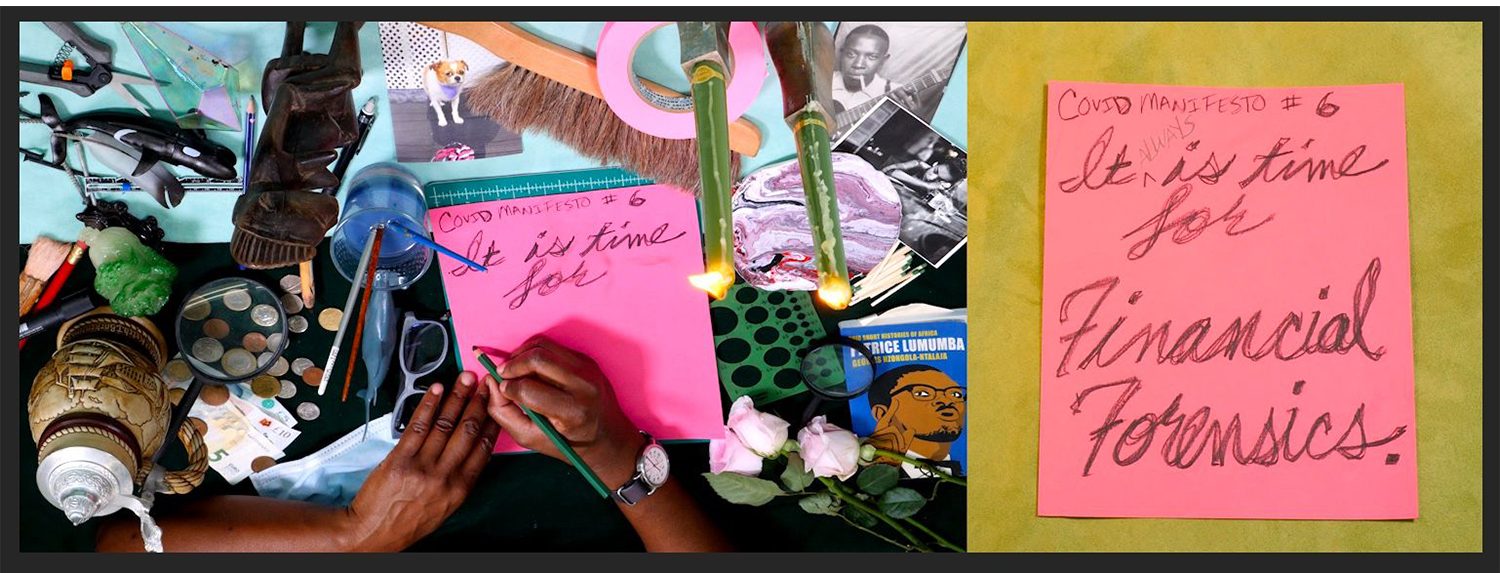

Best known for her experimental filmmaking and multimedia works that address issues facing Black women in the US, Cauleen Smith’s recent COVID MANIFESTO (2020) was first released on Instagram prior to its exhibition at The Showroom, London. Initiating the project at the start of the US’s first lockdown on April 13, 2020, Smith shared photographs of handwritten notes outlining her lockdown experience. These often use satire to unveil racial capitalism by addressing police violence, environmental destruction, and the social disparities of COVID-related deaths, while other posts envision a future led by Black women. For this work, Instagram becomes a medium for the artist to share her thoughts, frustrations, and inspirations amid a global pandemic. It is a tool for storytelling without the branding — a safe space to share experiences in dark times, and a platform that pairs self-care with protest.

In turn, Everest Pipkin creates tools for the resistance of algorithms. A drawing, game, and software artist from Central Texas, Pipkin produces small works using large data sets. Their Image Scrubber app was developed in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder explicitly to protect protestors’ identities. By removing metadata from digital photographs, Image Scrubber allows users to selectively blur faces, protecting protestors’ identities while still documenting the act. The technology’s political potency therefore relies on its resistance to computer vision algorithms through a willed deaestheticization of an individual’s identity. Just as algorithms study user behavior to promote commercial interests, Pipkin exemplifies a new wave of digital artists that contests algorithmic operations while working within their framework, in order to expose their limits.

Fascism seeks to give the masses an expression while preserving property. The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life.17 (Walter Benjamin)

It was Benjamin who saw the aestheticization of politics as fascism in action — a spectacle by which the masses express themselves without achieving recognition of their rights. But his analysis also poses the question of whether the aestheticization of Instagram activism is really pushing the movement forward, or if it is fueling a contemporary fascism that might restrain it. Hank Willis Thomas has shown that Instagram can serve as a platform for community action as well as the critique of brand identity. While Cauleen Smith works to craft a space for self-care in conditions of solitary confinement. Everest Pipkin shows that social media’s aestheticization of identity politics can be contested by uncoupling identity from aesthetics according to the will of the people. Because, as Lisa Nakamura reminds us, social media is not simply a game of aesthetics; it’s also a means of safeguarding freedom by giving us sovereignty over ourselves.