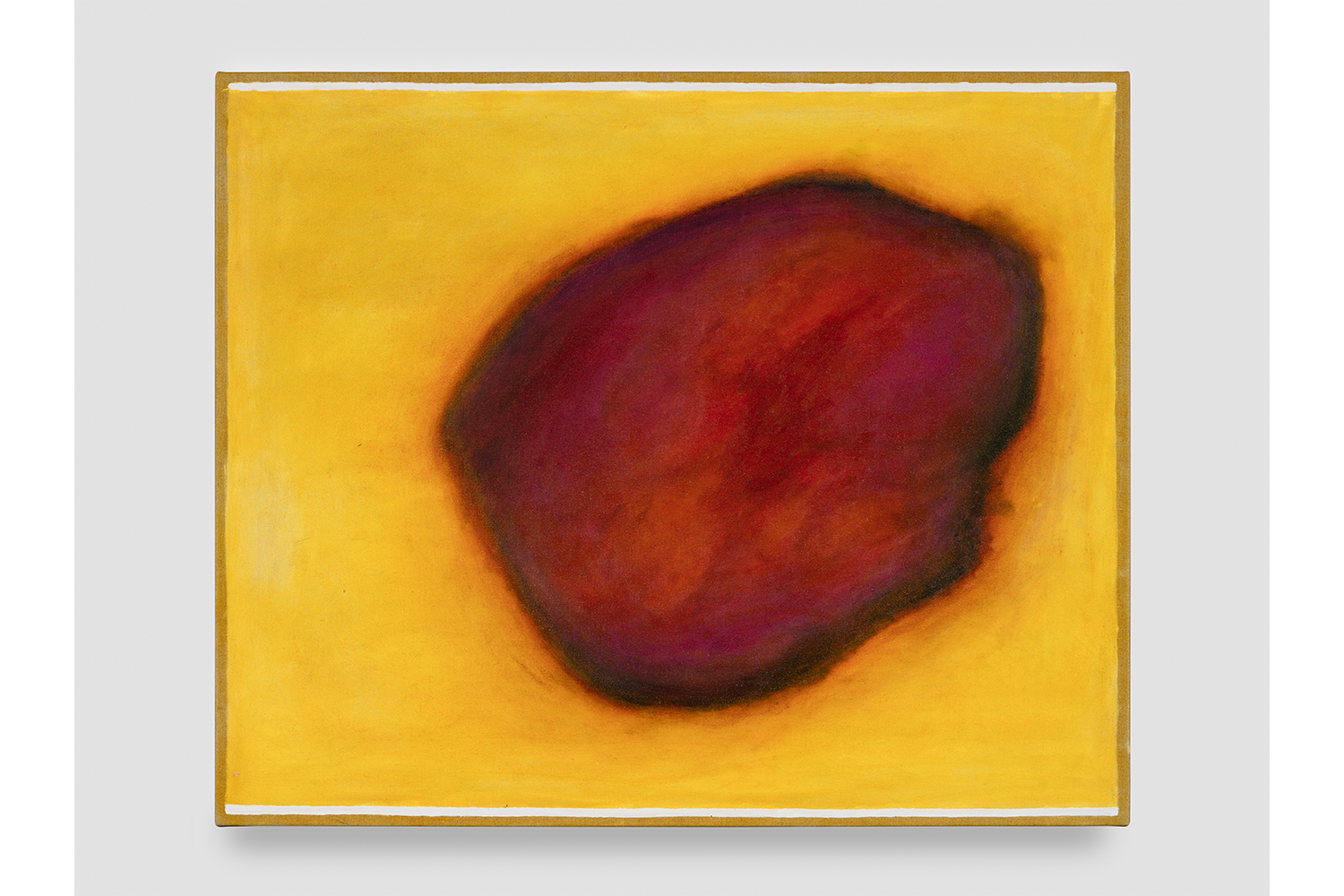

At first blush, the wound appears amoeboid. Afloat in decontextualized, atemporal amber, its charred kohl perimeter the blackness of clotting. Toward the center, the colors roll irresolvable with viscoid sociality: blistering rhodolite and burnt umber fruit-draped by soporific plum and black grape. Sunbird crimson, amaranth, addled by bruisey jaundice. An incomplete frame of two fine white lines leads to exposed canvas at the outermost border, expressing breath, vastitude. This wound is an accidental encounter of life in alterity, both synchronal and static, a fleshly meteor healing at the surface: a maturing, somatic bloom.

In this work, The Between is Ringing (Great Wound) (all 2020, subtitles hereafter), the artist settles within the restorative risk of transformation. Leidy Churchman’s paintings summon the slippery coexistence and reciprocity of subjectivity and alterity. Indeed, Churchman’s previous subject matter — of everyday signs, objects, and media aligned with abstract meditative esotericism — encourages the construal of temporalities, letting subjects arrive with interdependency. For “The Between is Ringing,” Churchman, a practicing Buddhist, attends to an old Taoist saying in reference to the Buddhist principle of dependent origination. The process lends this exhibition a philosophical air of immersion-as-elucidation, manifesting a kind of positive disintegration that, as the wound implies, may result from a violent eruption of tension: revealing, abrasive, but ultimately enlivening.

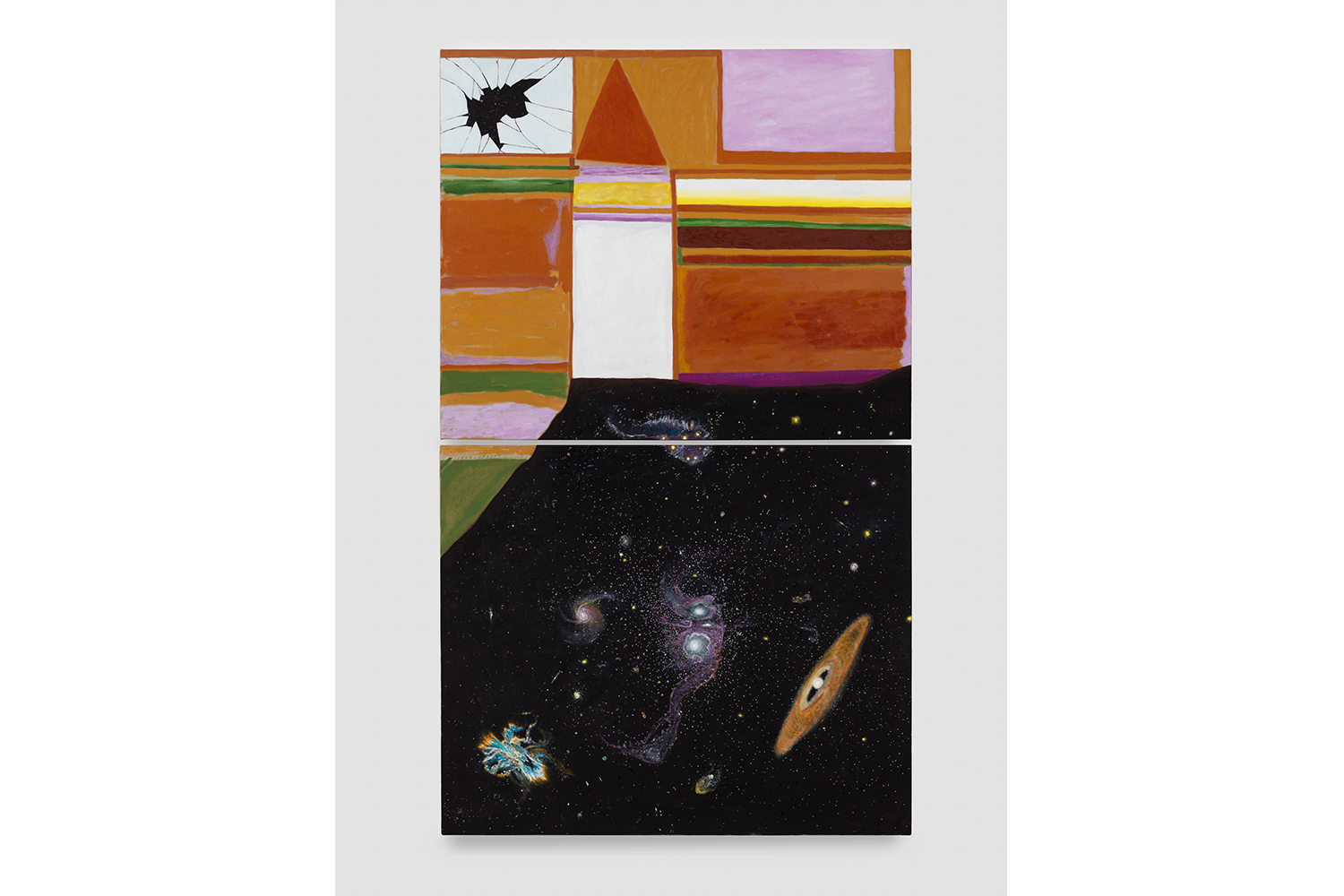

These water lily occasions of attention are meditations that admit a raw description of self-othering as coterminous with self-unfolding. Here Churchman’s psychic exfoliation approximates a collapse into a greater, unspecified intensity of presence. In (Diptych), two oil-on-linen paintings rest one atop the other. In the higher painting, an abstracted paneled interior depicts a white door alongside oblongs of cinnamon, ochre, and diluted pink interposed with rectangles of white, fern-green, and chrysanthemum-yellow. In the top-left corner, a window is shattered like eggshell, revealing a view of the universe. Beneath the doorway, all structure dissolves into astral life in a lower panel comprising an open galaxy: our powdered cosmos of stirred, opaline nebulae, luminous plasma, and the rime ice of starlight. In fractured specificity yielding to capacious multiplicity, the shaved coconut frame of (Diptych)’s cracked window notices that beauty’s coherence (much like interiority) was always a mirage, its best face rupture.

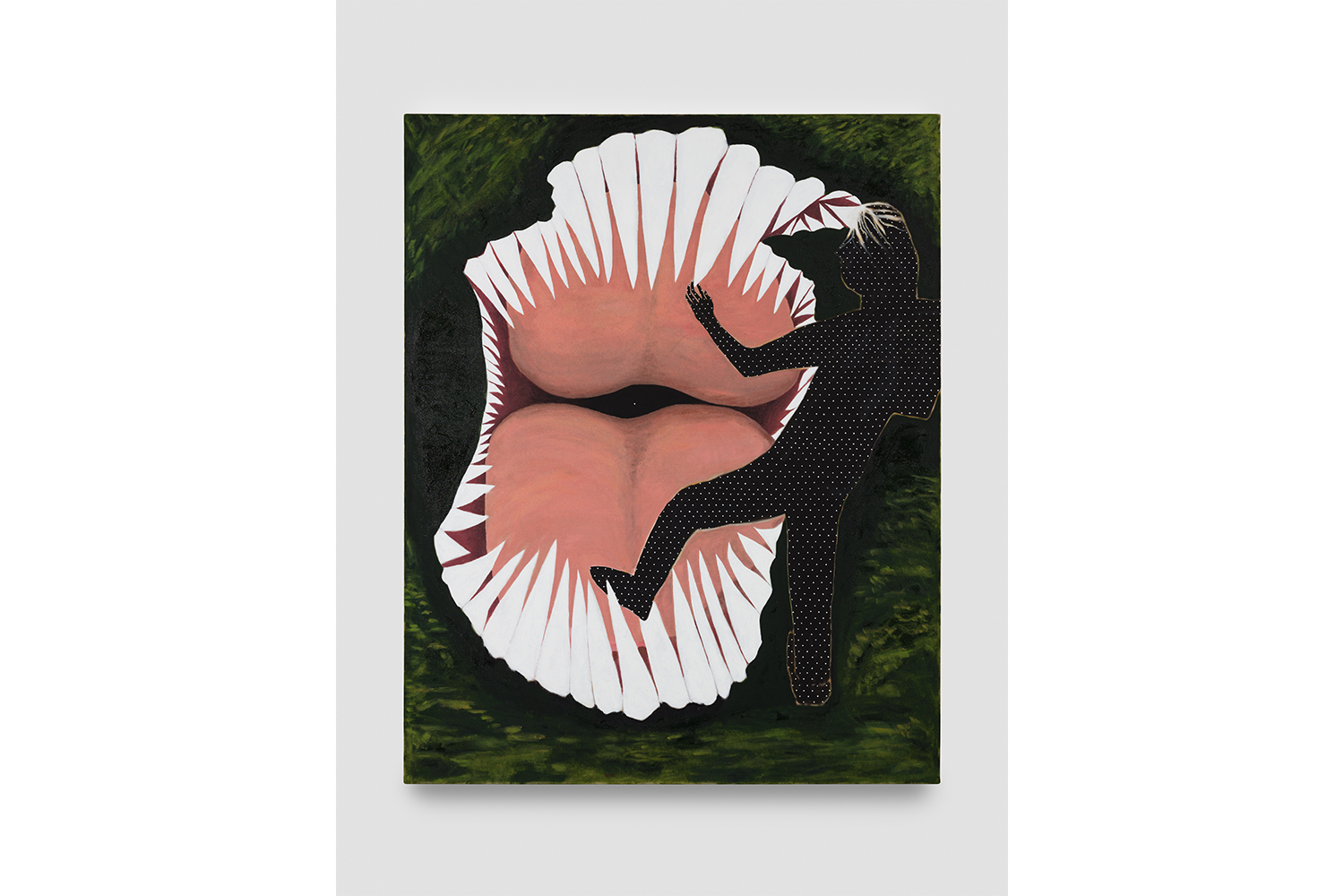

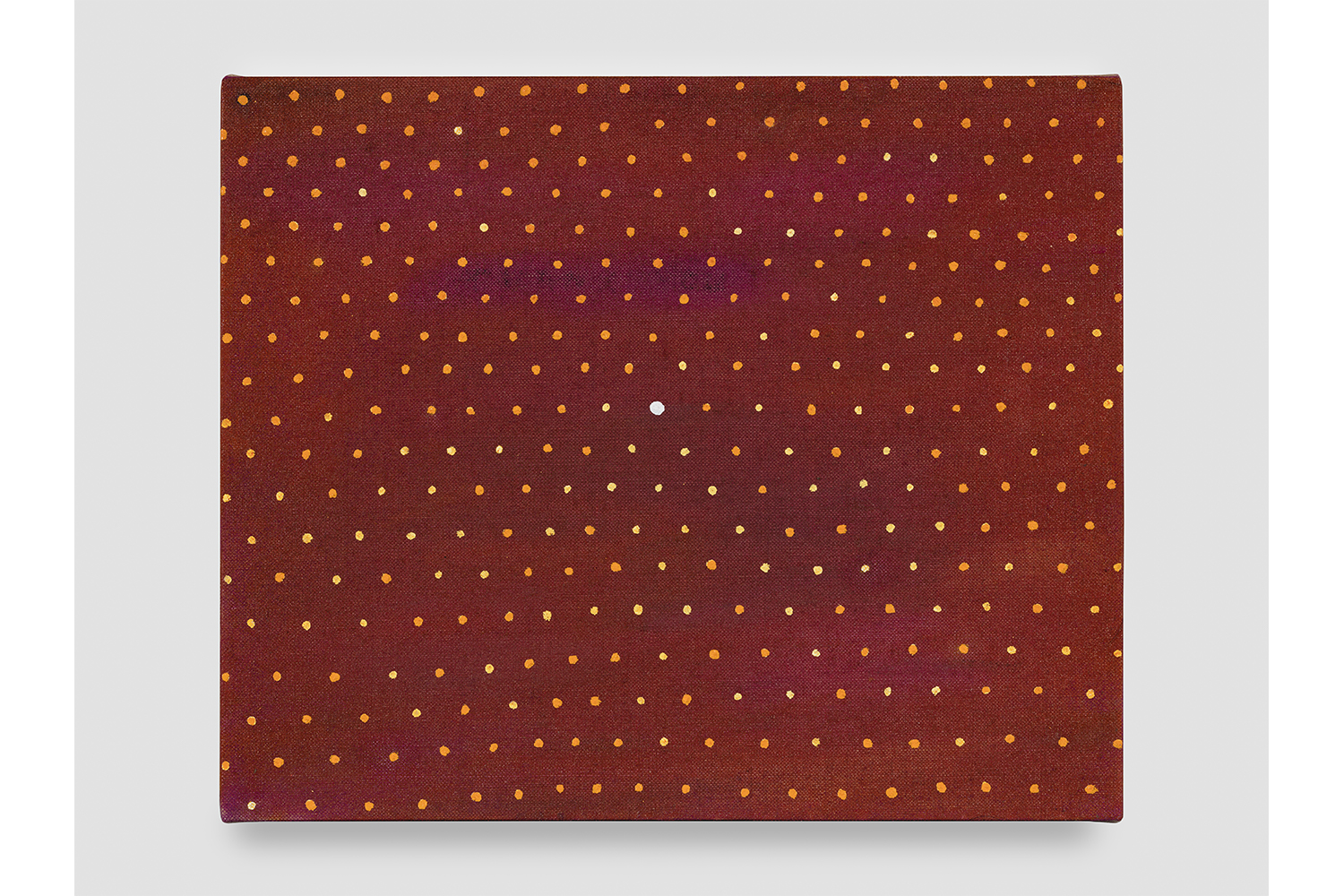

Churchman once described painting as “an aquarium of traces — looping but rogue at the same time. Maybe it has a lot to do with empathy.” This exhibition feels like such an aquarium, where paintings decelerate looking in their correlative recurrence and refraction of traces. Theirs is a fragile, articulated mutuality: the palette of (Great Wound) is magnified and sprinkled with mandarin dots, one white, in (Sparkling Bruised); such dots transmute to seed-studded surface for the tremulous strawberry heart in (Strawberry) (Braiding Sweetgrass); the fruit’s point of zigzagged kiss recalls the corkscrew that burrows into the demon’s tooth of (Milarepa’s Biggest); floating in the very center of this demon’s mouth, a white stipple.

For (I Am) we realize Churchman’s utterance of the “I” in a groundless scene, a transitive place containing multitudes. The flurried morphology of the earth is now a distant, bite-size gem beringed by gradations of unknowable celestiality, including a halo of white dots and their orderly chiming. Marshy, mountainous, salamandrine, riparian — this place should be left in its bounteous, virescent-obsidian wordlessness. In Churchman’s marbleized identification, one finds an embrace of illegibility, pitching the “I” to see it shook to pieces, like the window, ringing now. This illegibility is not merely visual; it is hard to parse and better unspoken, but if permitted by oneself to unfold, felt.