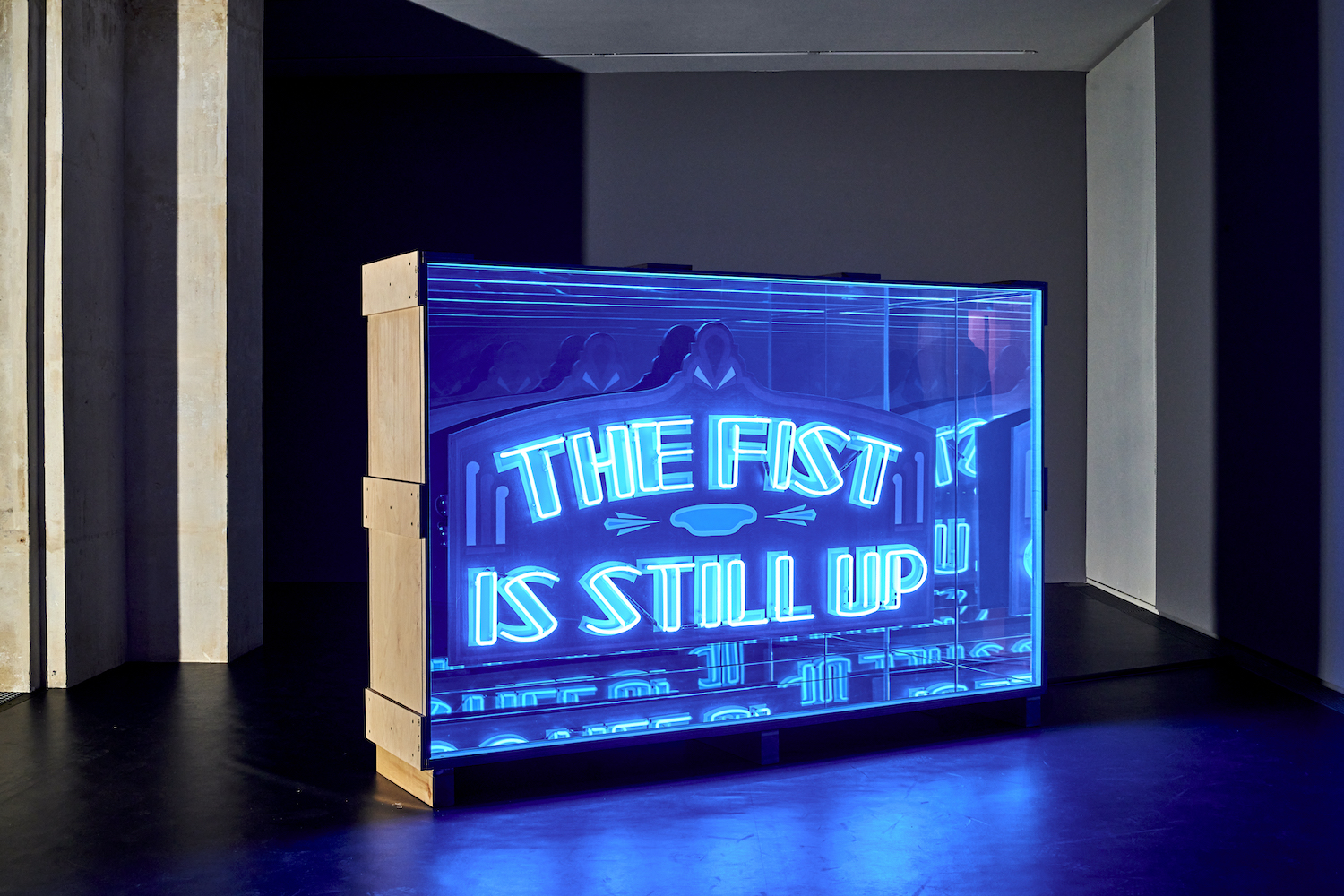

A good novel can give one a feel for an idea as if it were a flesh-and-blood person. In this sense, Herman Melville’s novel and character Bartleby, an embodiment of passive resistance, infuses a range of modern philosophical thought — from Derrida and Deleuze to Rancière, Agamben, and Badiou. At the dawn of a new millennium, faced with greater urgency as certainties and ecosystems collapse, one starts to look for a new Bartleby: a character, figure, or symbol that could embody the turn toward a secessionist stance, one that altogether disidentifies from inherited centralized systems. Of this, Wu Tsang’s practice provides a telling example. In one of the American artist’s earliest works, Wildness (2012), the Silver Platter bar, a historical safe space for transgender immigrant women in Los Angeles, serves as a narrator to the documentary. In Tsang’s newest body of work, another quasi-protagonist surfaces: the Penrose triangle. In “visionary company,” her current solo show at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris, the illusory geometrical shape, an infinite staircase both ascending and descending, is the set of the main film, the three-channel video installation The Show is Over (2020), as well as an autonomous small-scale sculpture, PIE root “to see” (2020). Not unlike the bar, of which a blue neon sign (Safe space, 2014) provides a glowing reminder in the new show, the Penrose triangle is both a space and a character. As such, it also serves as a stand-in for the bodies that move around it, freeing them from having to appear in full light themselves.

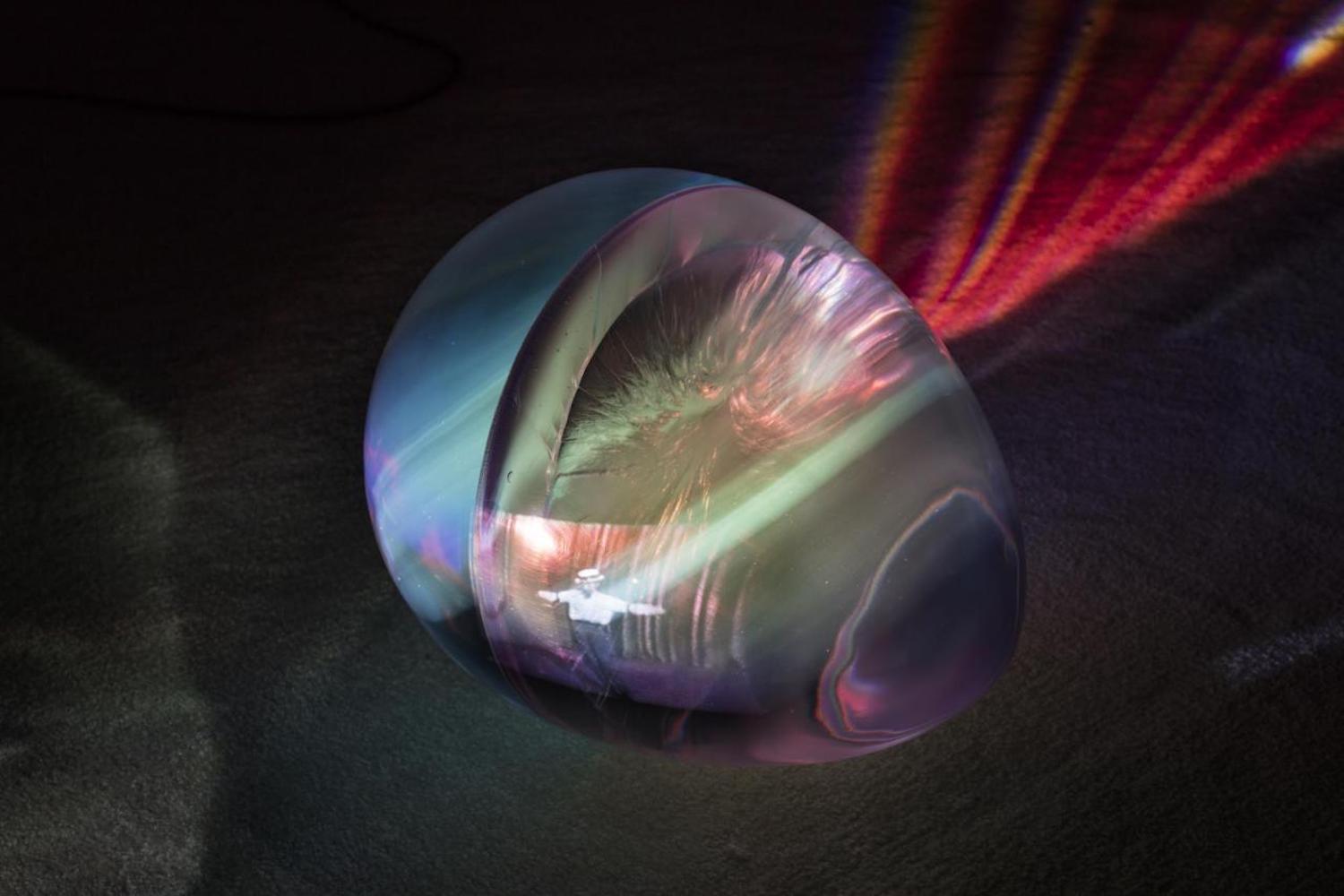

In the main film, co-produced with Tosh Basco (aka Boychild), with whom Tsang co-founded the interdisciplinary performance group Moved by the Motion in 2016, a group of Black, suit-clad performers evolve on a dramatic post-apocalyptic stage filmed via Tsang’s characteristic whirring camera movement — or “cameography.” Apples rot away, mud lays thick like clay, ominous oily water rises. Sometimes, interrupting a succession of eucharistic tableaux vivants, they climb the stairs to find a temporary respite. Throughout, they declaim fragments of the poem “Come on, get it!” by scholar Fred Moten, which helps bring the underlying questioning to the fore: the problem of representation. “All we got to do is come out to show you we ain’t got to show you shit,” proclaims one performer, his words still echoing as one moves on to a second video, The more we read all that beauty the more unreadable we are (2020). Collaged from material assembled during the filming process, it also features an excerpt from an archival televised interview with writer James Baldwin, who posits looking and desiring as complex recursive loops. Amid the textual layers of the glass centerpieceSustained Glass (2019) one can make out the sentence, “There is no nonviolent way to look at somebody” — also the title of her 2019/2020 show at Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin.

The last piece of the show, a short, fast-motion projection (Sudden Rise, 2019), compiles visual material around the origin of single-point perspective and its post-Enlightenment imperialistic developments. The Penrose triangle, on the contrary, eschews monofocal capture and, as such, provides a refuge for fugitive allies aspiring to disappear from the public eye. There, they can appear on their own terms, just as they can chose to remain unreadable. A symbolic form of a contemporary practice of refusal, it translates the need for new spaces, new structures, new communities: when faced with a pressing urgency, refusing is not enough anymore. As an activist, Wu Tsang is attuned to one of the most pressing tasks of our time, the dismantling of colonialist-humanist norms once and for all. As an artist, however, albeit a multidimensional one, her show “visionary company” still, and paradoxically so, feels representative of a given center: that of current, well-oiled artistic tropes, failing to convey self-determination other than on a vaguely poetic surface level.