One of the biggest hindrances of institutionally packaged and formatted creative work is the tension between producer and spectator — the constant negotiation between who stands on the inside and who remains on the fringes. It’s a fine line, often obscured, yet Luke Ching deftly treads it. His work strikes a unique chord: an ability to identify and dislocate certain injustices; and to transform them within, but also outside of, the context of art. By tweaking his subject matter in a delicate way, he is able to bend this boundary using a highly unique conceptual tone.

Ching’s practice has always skirted between the lines of absurd humor, micro and macro activism, and a tongue-in-cheek irreverence, often with a particular focus on labor and migrant rights as well as other political issues specific to the context of the artist’s home, Hong Kong. The title of the exhibition, “Glitch in the Matrix,” is quite literally a reference to a scene in the film The Matrix in which there is a hiccup in a simulated reality — suggesting an analogy to the increasingly irrational and illogical condition of modern life. The exhibition explores on multiple planes the feeling of being trapped in our hyperreal society; indeed, the layout of the exhibition mimics the format of a prison cell or detention center. Ching toys with the disorienting panoptical concept of being watched without knowing that you’re being watched, no doubt alluding to increasingly worrying local political changes.

Upon entry, there’s a caution sign alerting the viewer to take off their left shoe before entering the exhibition, provoking a sense of irritability and discomfort for the viewer. Ching ruminates upon the idea that the longer one views the exhibition, the greater the possibility that one will become accustomed to such absurdity. Bordering Take Off Your Left Shoe Upon Entry is Face Shift (both works 2020), consisting of Ching’s identity card photo arranged on the wall in the shape of a prison door, in part a reference to how he tried to “hack” the system by having his mouth open in the picture.

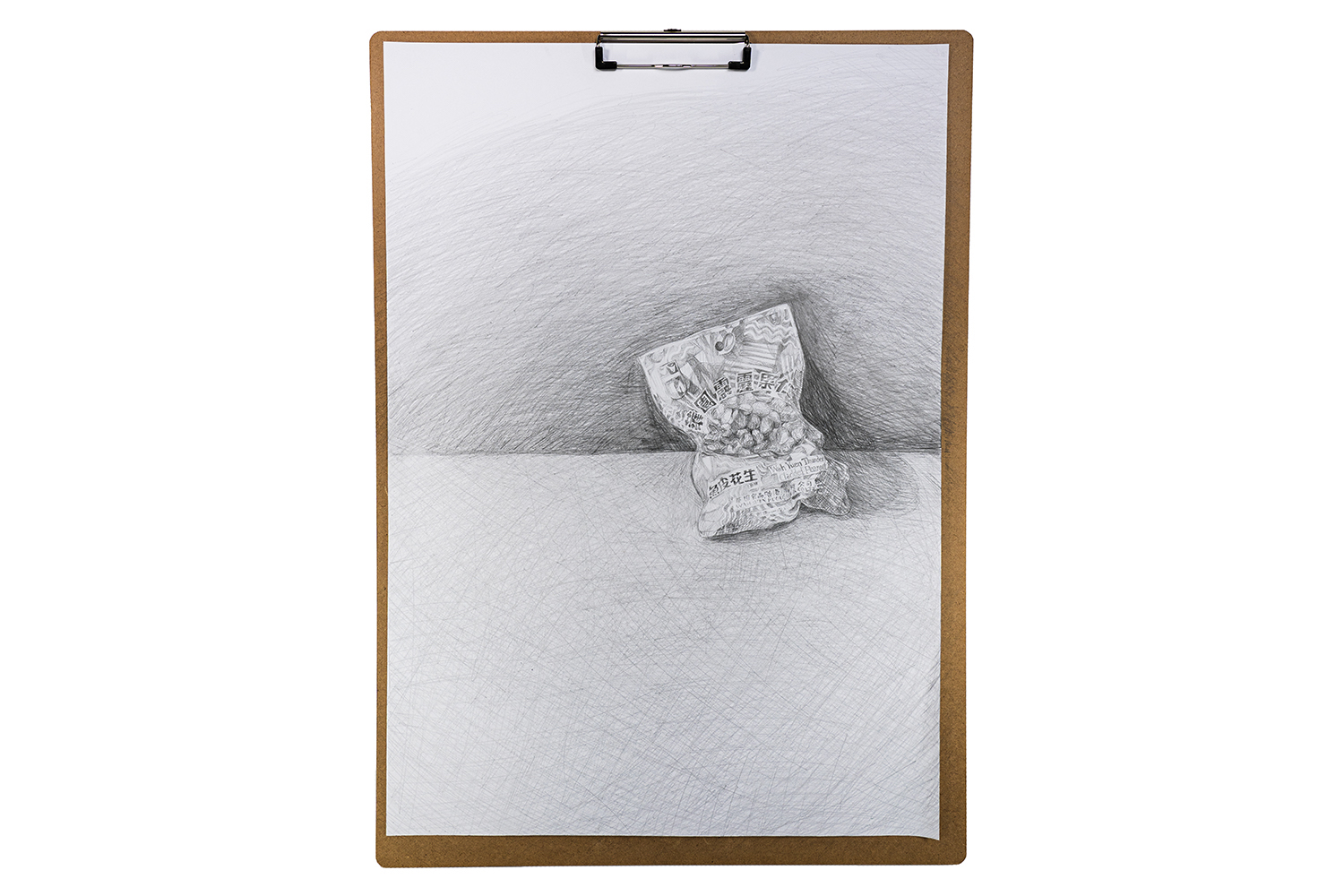

Still Life (2020), a beguiling series of pencil drawings depicting quotidian objects and brands like Darlie toothpaste, Dettol liquid soap, and Pears bar soap, depicts everyday objects that CIC detainees (a controversial detention center in Hong Kong for migrants and refugees) are allowed to bring into the facility. The work describes a paradox, as detainees typically have no money to spend on these everyday necessities. Upon closer inspection, Ching has altered the brand slogans in the pencil drawings to reveal cryptic, motivational, or punning phrases, permeating the work with a sense of farcical ominousness.

The subliminal altering of these brands seems to reflect the brainwashing experience of detention. In particular, one aspect of detention is that none of the detainees are aware of the length of their detainment; therefore their sense of time is entirely distorted. Two clocks are placed on adjacent walls, each set to 6:00 pm. Here Ching highlights another contradiction: our reliance on the artificial concept of time, but also just how inhuman it is to have that right taken away.

“Glitch in the Matrix” is a multifaceted cacophony of veiled socio-political reflections and provocations all coalesced in one room. If anything, the range of fleeting topics, from CIC detention to labor rights, feels erratic and slightly convoluted, even if the wider framework does tease out an observational critique of Hong Kong’s diminishing freedoms. Ching definitely piques one’s curiosity about subterranean and miniature societal infringements in both a lighthearted yet sinister way; however the power of each work could benefit from a better sense of overall coherence. Nevertheless, Ching’s sense of humor is pervasive, reminding us that these glitches and blind spots offer solace from a social reality unrelentingly governed by neoliberal and authoritarian hegemony.