“Regarding Glee I would say two things: 1. It’s not like my work. It is my work; and 2. I want to gay marry Ryan Murphy.”

– Deborah Kass1

When Kurt and Blaine—the much-anticipated gay couple in Ryan Murphy’s Glee— twinkletoed through an inevitably erotic rendition of “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” I was in a dorm room filled with straight guys and their girlfriends who paid no attention to the emotional dénouement onscreen. I, however, was glued to the TV, watching their handsome faces, their lithe bodies so unlike mine, their filmic love that, in that moment, felt not like an imitation of life, but rather like reality. It was a reality that did not belong to me (I felt and feel more like Deborah Kass’s ugly but kind turkeys after Monet) but a world of possibility nevertheless opened up. I knew, we all knew, that this was coming when Blaine crooned “Teenage Dream,” itself a favorite song of mine, for Kurt, but with snow floating through the air and rape-adjacent lyrics, the dream was finally consummated—problematically and beautifully.

I only really became gay when Kurt and Blaine finally kissed, and I think Kass makes me even gayer every time I see her paintings. We know that she reformulates, loves, and critiques the heteropatriarchal underpinnings of modernist and postmodernist painting. We know that she likewise reformulates, loves, and critiques the queer (but still masculinist) trajectory of appropriation, reaching its apotheosis in Warhol, who we all know hated women because he hated himself. He loved women beset by tragedy because he felt that he was just as tragic but not as beautiful, more akin to a turkey than Marilyn. This might be the truest core of art made by gay cisgender men, and Kass has always humorously and poignantly made that clear.

Art history is only one lens of many, though. What of this discourse: Deborah Kass is a Jewish lesbian-feminist activist-artist who loves musicals and pop music and cries during movies and remembers exactly where she was when she first heard a certain song? Pace Griselda Pollock who wrote: “To label woman, Jewish, lesbian, is to impose from outside an already known frame on another and thus to contain the labeled other.”2 Yet so much of Kass’s work centers on that labeling, because the optimistic way of describing labeling is identification: identifying as someone who loves musicals and pop culture, both debased by self-selected intelligentsia in all disciplines, someone who is sentimental, someone who loves painting and not in a “Painting Beside Itself” kind of way, someone who is really, really gay. Above all, Kass therefore is someone who is unafraid to confront shame, a term that, in art history, we mostly associate with cocks, blood, bondage, shit, bottoming, and cum. Usually our interest is in cis gay men of a certain era using those media, but one could maintain that all those things (save bottoming, maybe) are more normalized than flying from Los Angeles to New York to see Vanessa Carlton in Beautiful: The Carole King Musical on Broadway. In any case, I would say it is true though that cis gay men purport to really know what it is to be a lesbian, but I am sure that lesbians actually know more about us than we do about them. Call me binary.

This centering of identification and attachment feels so pressing because Kass always reminds me that on the flipside of shame is love, and on the flipside of EMERGENCY is intimacy, and that might be the queerest realization of all. Years after my Glee transformation and taking a whole class on the history of musicals, I moved to New York and, as one does, found myself enamored by a boy who was handsome and distant. Since he was a student in classical music composition at Juilliard, he hated anything to do with commercial music, especially musicals, top 40, and film composers like John Williams. He hated RENT and he hated Lady Gaga. I can only imagine his feelings about Katy Perry, who was never quite “talented” or “weird” or “insider” or “sad” enough, hence the different but equally important registers of my love for “Teenage Dream,” “Bad Romance,” and “Video Games.” He actively hated Funny Girl, which seemed to me an odd passion. Liking such things, he said, was a gay stereotype, and he was beyond that; he was not defined by his sexuality; he sucked dicks, but he was free, and I was a stereotype. So, I told him that I hate musicals too, when what I truly hated was him. Sufjan Stevens played disinterestedly in the background.

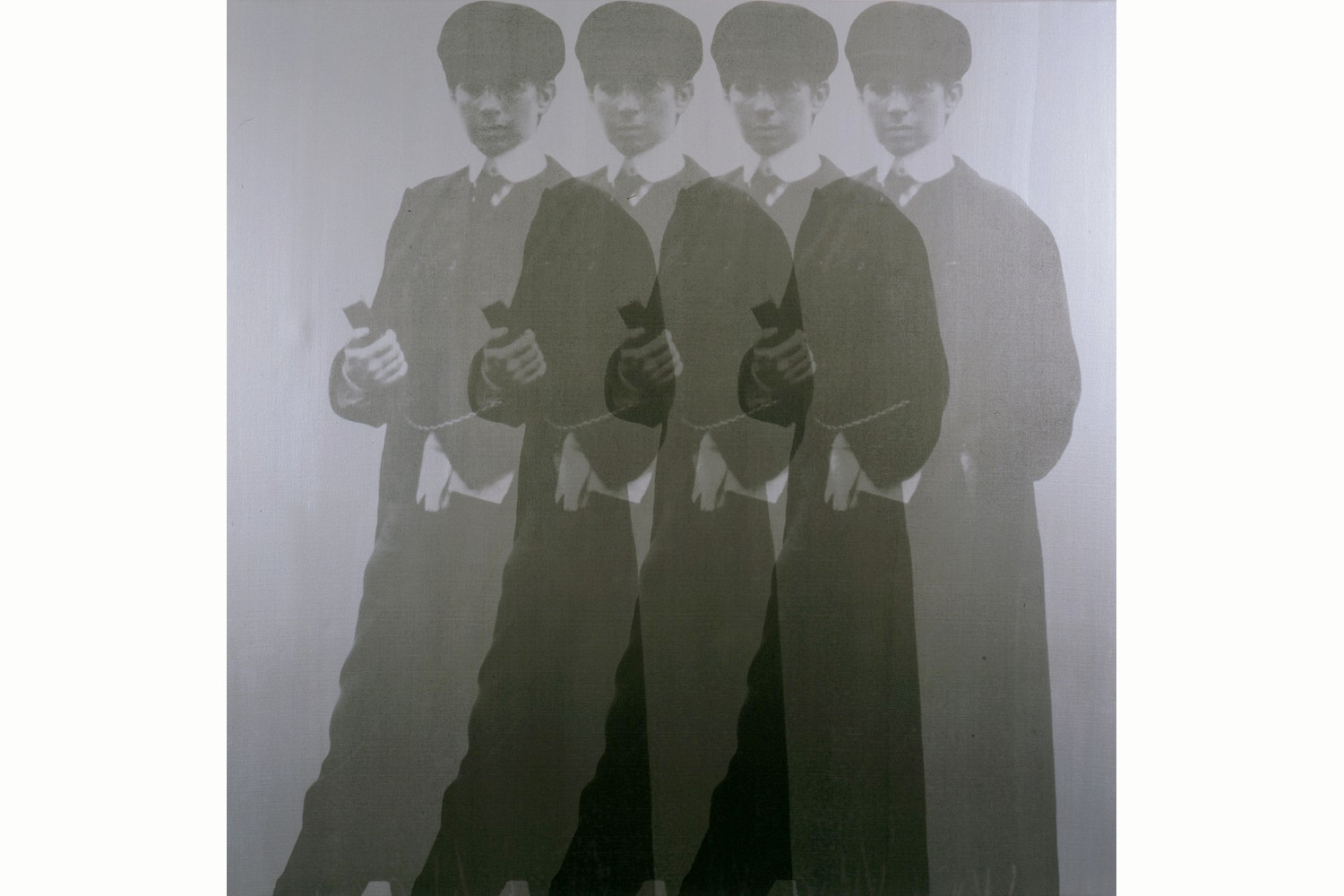

Returning to a more squarely academic appreciation of Kass, Pollock writes of Quadruple Ghost Yentl (My Elvis) (1997), “Kass’s work confronts the viewers with a repeating figure that seems to address them in that guise of transvestite performance. Yet if it were so simple, so purely narrative, there would be no art.”3 Putting aside the fact that transvestitism is not simple, it is the impulse of the critic and/or historian, especially those who identify as queer and/or feminist, to legitimize artists, to make a place for them in an exclusionary canon. This, however, to recall Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, is a paranoid emotion stemming from a fear that culture as such is not critical enough, not interesting enough, not deconstructive enough on its own without artists and theorists as interpreters. But Glee is Kass’s work, as she herself says. Kass’s work is Glee. That is not the same as Kass’s work translating or deconstructing or referencing or appropriating or even illustrating Glee. What Kass has done, as have her colleagues like Laurie Simmons, Barbara Kruger, Marilyn Minter, and John Waters, is to not just point to and pick at a zeitgeist, but to embody it, to exist in a parallel fashion to it, to refuse to hold it at arm’s length with academic remove. This is likewise not the same as earnestness, at least when defined with masculine permissiveness à la Slavoj Žižek or David Foster Wallace or Douglas Crimp. Kass’s painting is more of a process of learning to critique what you love and love what you critique, which has always been a queer heuristic, and to find within dominant culture empathetic and intimate modes of survival. We might learn to ask, for instance, why we, as gay cisgender men, love the whiteness, classism, and spectacle of Broadway, or we might learn how to love someone despite our different responses to groups of people randomly breaking out in song. We might learn to love within discourse and without it and theorize one alongside Everybody.

Deep in the recesses of my iPhone, I have a picture of Kass on a merry-go-round. Her centrifugal motion (to cite another American popular music standard by Faith Hill) was not so much day after day after day after day (to cite Kass citing Sondheim) but rather a true moment of joy and connectivity in pre-Trump, pre-COVID, pre-Los Angeles, post-9/11 New York. It was pouring out and I had been invited to the opening of Kass’s OY/YO by her former gallery’s publicists. At that point, I had not yet written about Kass or met her in her studio, so I mostly looked on with youthful awe.4 I, like Kass, was anything but blasé at that point, despite it being the height perhaps of millennial apathy. I do not think this is inherently good or valorous that we were hopeful. It is just to say that in my first year in New York, it felt like I was seeing everything for the first time, which is also how I imagine Kass relates to culture and space and the city and public histories and private histories and queerness. I had no discourse for New York then, only a teenage dream.

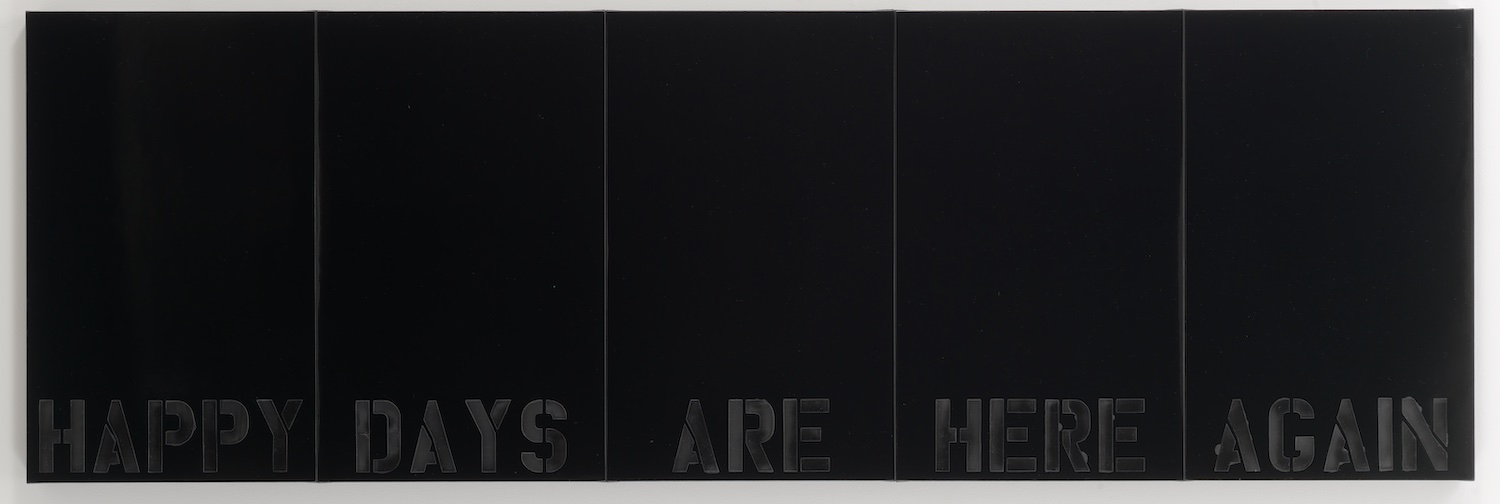

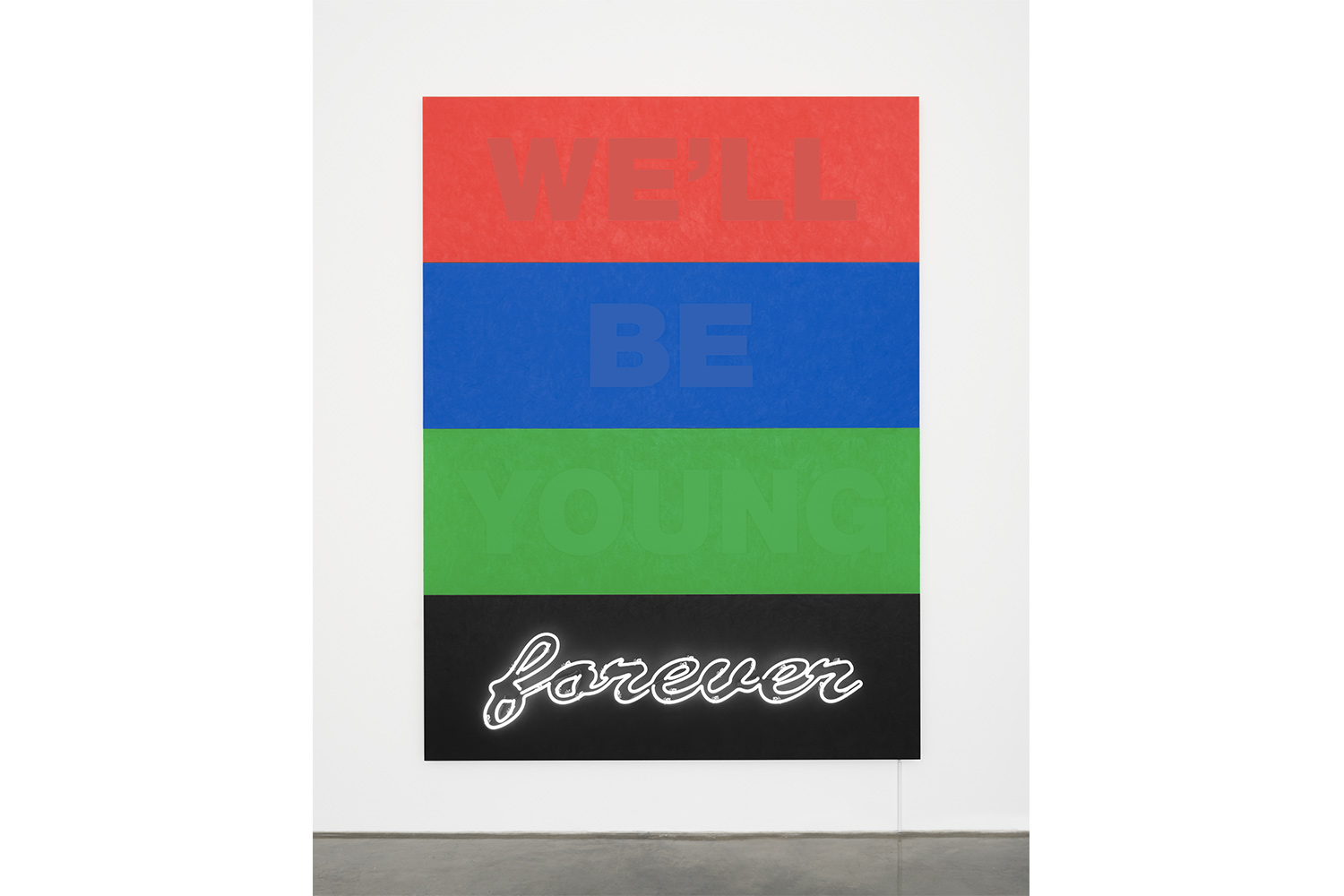

In the course of finding that beautiful picture of Kass, I scrolled through years of iPhone detritus from my years in New York, and that scrolling, even though it is a passive process in some ways, left me bruised. So, I do not mean to say that Kass is blithe or that art writing should be blithe. Pollock is right about Kass in that works like We’ll Be Young Forever (2015) ultimately avoid narrativity, and in some way, pleasure, because we will not be young forever, but that is a biological fact and not an art historical one. Indeed at some point even the most upbeat of songs disappears abruptly, as with Kass’s homage to The Sopranos in Don’t Stop (2019) or when Solanas put a slug in Warhol, reverting us to the most mundane of experiences—frantically checking if something is wrong with our TV, our lives. Though, and this is part of Kass’s range, a reference to The Sopranos might not hit you, but you might instead recall Michael Jackson’s or Fleetwood Mac’s requests that we not stop.

When I met Kass, I still believed that Darren Criss might indeed be gay, though it was probably just a delusional screen against the thought that a straight guy had played such a major part in my coming out. Perhaps what makes We’ll Be Young Forever “art” in Pollock’s definition is not just the fact that the painting both honors and debunks a (teenage) dream, but that it could refer to Katy Perry’s version or Glee’s version, destroying thereby the archetypal original. And yet they are all originals (Kass’s “Teenage Dream,” as well as Perry’s and Blaine’s) because in the most Warholian way possible, Kass’s work is both historically specific and everything all at once; it is the Great American Songbook, which also has no original and is nevertheless perennially original; it is a compendium of emotion, years piled and stored; it is optimistic and it is the death drive; it is making my students at City College watch the “Happy Days Are Here Again/Get Happy” duet by Barbra Streisand and Judy Garland knowing full well that they did not care and that it was for the benefit of my heart, and my heart only, and not the benefit of Art History.