“The Uncanny Valley” is Flash Art’s new digital column offering a window on the developing field of artificial intelligence and its relationship to contemporary art.

Despite striking differences in approach, Mimi Onuoha and Gretchen Andrew both represent to some extent artist-sociologists of the channels through which power is exerted and profit algorithmically extracted. The former surveys datasets and develops artistic strategies that politicize absent data. The latter inserts herself within the algorithmic structure of search engines in order to exploit and explode their inherent vices. Neither artist works directly with AI in the conventional sense of generating images through the training of neural networks. Yet it is the very liminality of their practices, situated between the fields of academic research, new media, and contemporary art, that affords them a critical vantage on the digital systems that increasingly classify and structure human experience and exploitation.

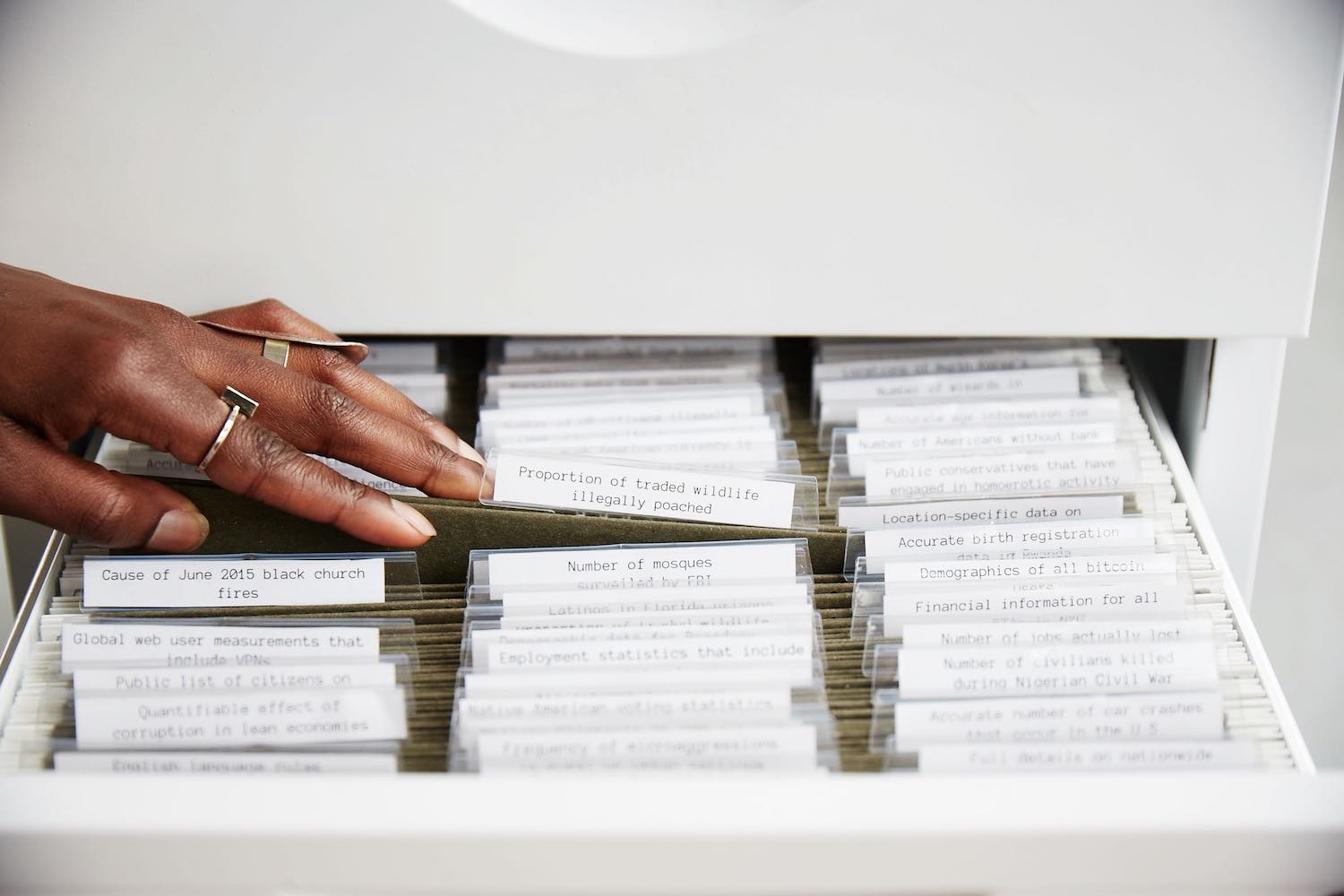

Mimi Onuoha has previously described how “the things we measure are the things we care about.” What we choose to exclude is the subject of her work The Library of Missing Datasets (2016): a white filing cabinet filled with empty folders whose tabs designate missing datasets. This missing data, for example “people excluded from public housing because of criminal records,” is further elaborated elsewhere in the artist’s research, which has overtones of Hans Haacke’s famous Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System as of May 1, 1971 (1971) that documented the fraudulent activities of one of New York’s largest slumlords. Couching his data in numbing repetitions of monochrome text and image, Haacke revealed the concealed ownership structures of tenement housing in a way that dared the spectator to ignore grim reality. Onuoha reinterprets such early prototypes of systems art in her critique of ideological interests, articulated through a minimal aesthetic. The obduracy of an entirely empty cabinet makes for a natural symbol of what structurally white societies choose to ignore and how mechanically they dispense with unwanted truths.

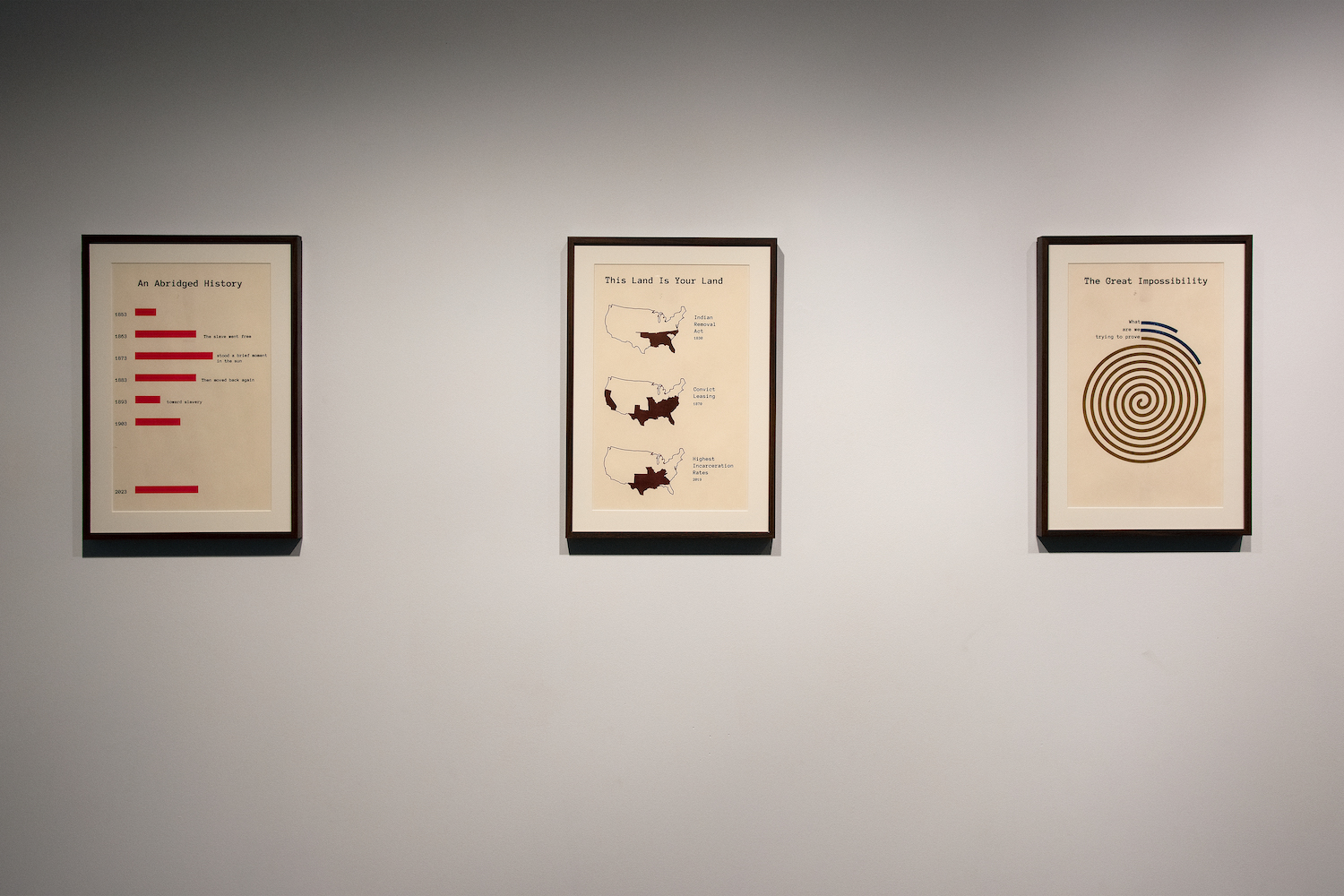

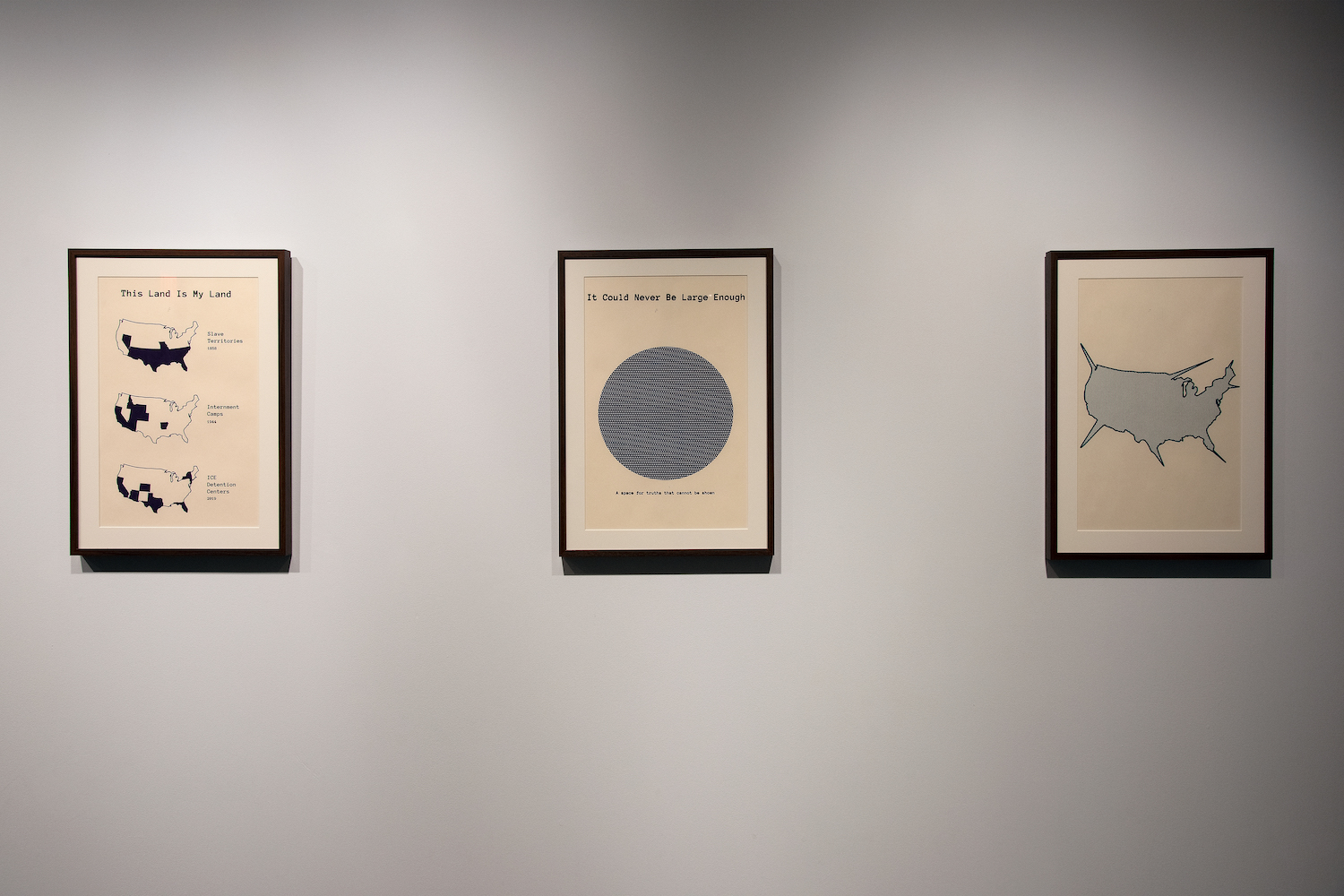

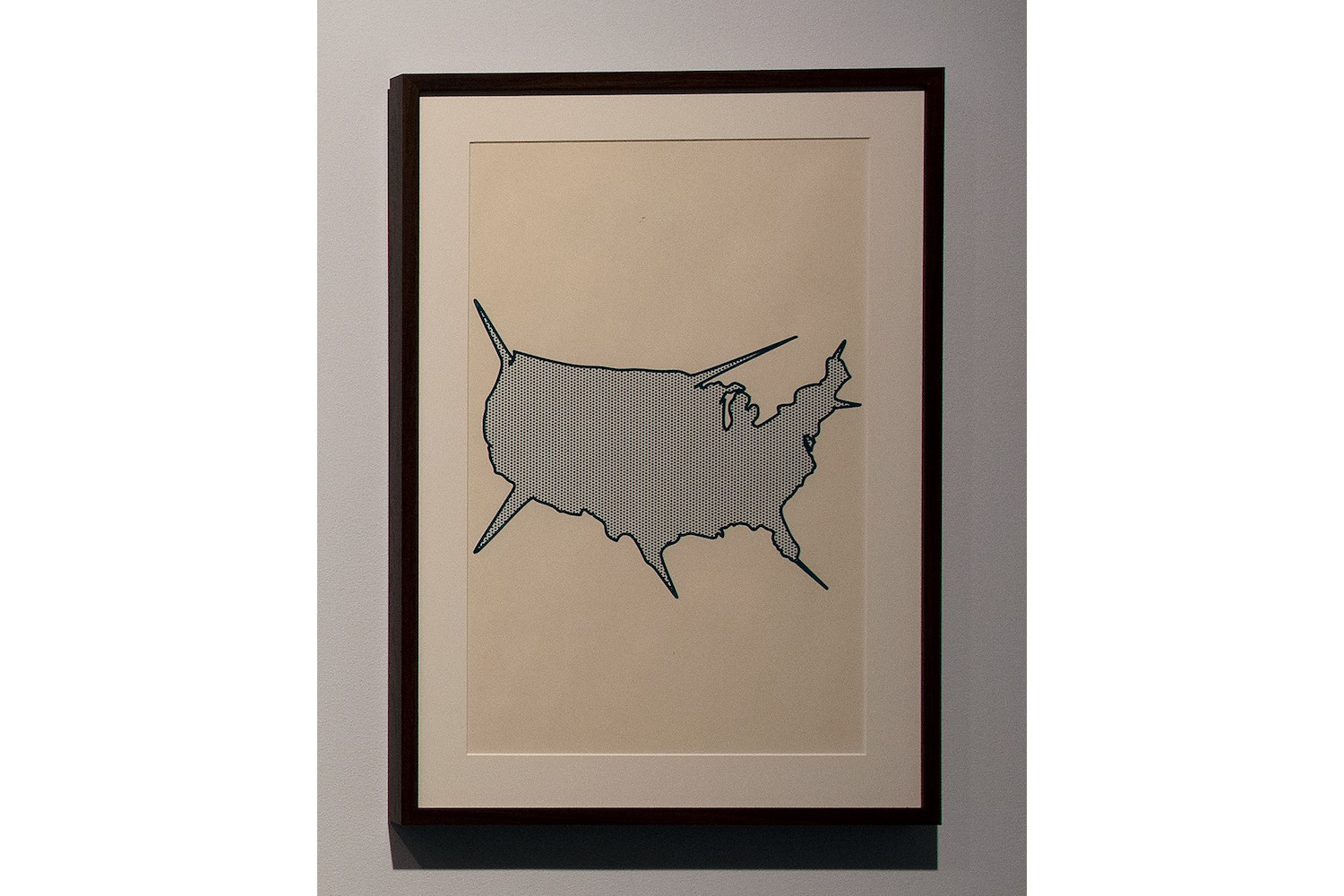

The paradigm of this is the refusal of the US Board of Labor Statistics to publish Black sociologist W. E. B Du Bois’s painstakingly produced study of the Black community in Lowndes County, Alabama, in the early twentieth century. Onuoha’s more recent In Absentia (2019) incorporates remnants of Du Bois’s (not destroyed) contribution to the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris: charts, graphs, maps, and photographs that document the everyday lives of African Americans in order to challenge grand narratives defined by racial stereotyping. Yet when reformulated by the artist for gallery display, it is the simple geometries and bold coloring of the infographics — their innocence as well as their abstraction — that not only resurrects the data but asks what it takes for society to find meaning in it. As Rob Kitchin has stressed in his book The Data Revolution, data should not be treated as “neutral, objective, and pre-analytic in nature” but rather “framed technically, economically, ethically, temporally, spatially, and philosophically.” In Absentia enacts this approach by interspersing different forms of data visualization — spiral bar charts, maps of slave territory, patterns of incarceration — with direct questions: “What are you trying to prove?” Coupled with printed pamphlets and immersed within an audio installation, the viewer’s process of reasoning is unsettled to the point where one becomes painfully aware of how much is missing and of one’s own will to misinterpret. Kitchin’s book reminds us that what is conventionally understood as data — the raw material “given” to us for consideration — is in fact capta, or what we choose to “take.” Mimi Onuoha’s work shows that this kind of collective misunderstanding is in fact political ideology.

Despite containing a wealth of potential biases, classification algorithms are largely perceived by the public as instruments of precision and truth. Onuoha’s neon sculpture Classification.01 (2017) invites spectators to experience the arbitrary operation of these algorithms, with two Naumanesque neon brackets turning on only when visitors are classified as “similar.” Hooked up to a CCTV camera, the sculpture leaves observers to interpret the rationale behind its decision, forcing them to accept the opaque operations behind their own surveillance. In his landmark book The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. Du Bois showed why access to facts, information, and knowledge matters, and how the availability of facts — who they address, who they’re about, and which knowledge is systematically encouraged — remains an ongoing problem in the struggle for genuine equality. Mimi Onuoha’s work reinforces how the automation of bias is currently preventing access to knowledge in ways that fundamentally undermine the functioning of democracy.

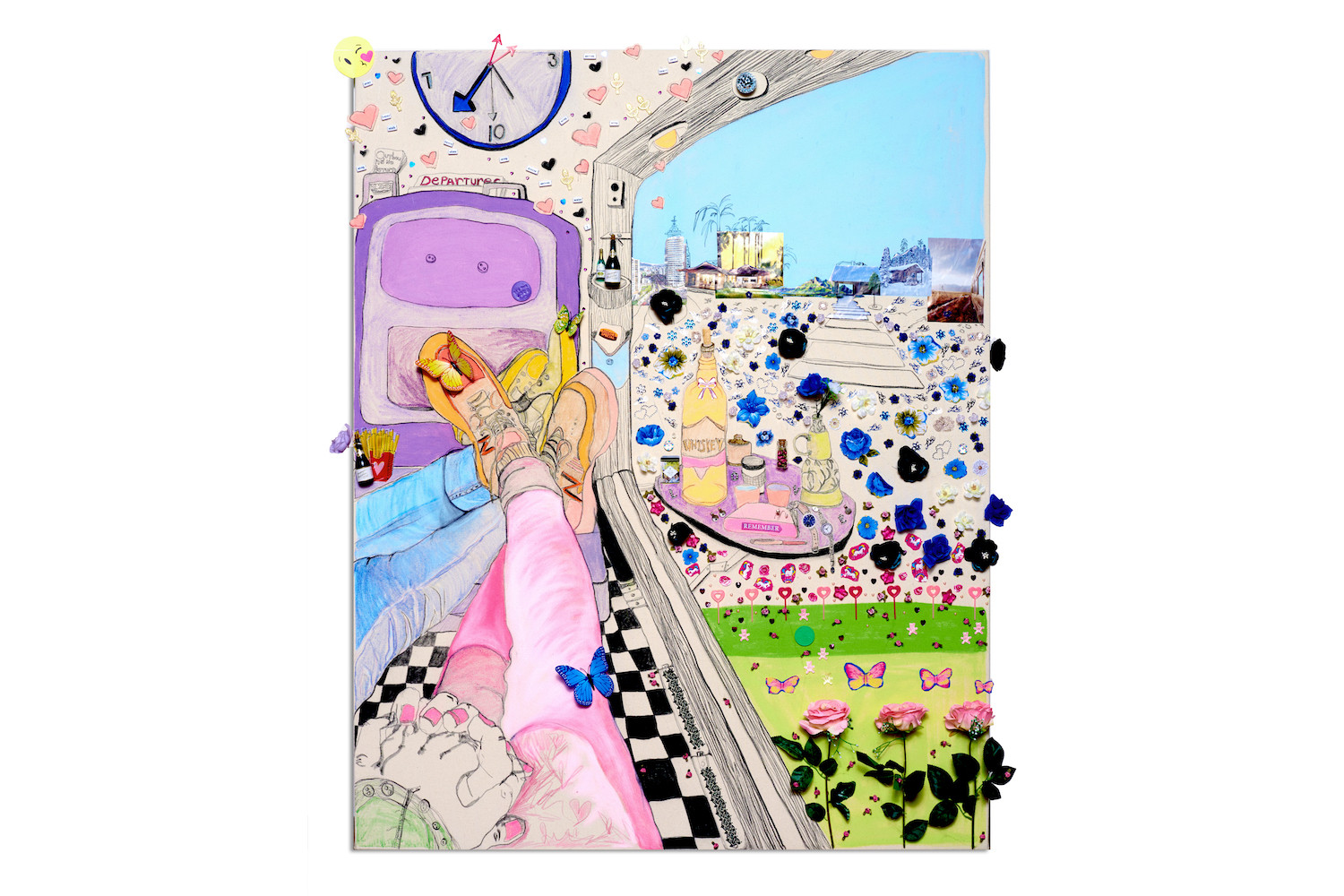

Gretchen Andrew’s training in information systems has shaped her use of a diverse web of media strategies, which together constitute her art, in order to exploit the weakness of, most notably, Google’s search engine algorithm. That her approach to being accepted by the art world is so brazenly kitsch, dominated by a Day-Glo cult of herself as a standard-bearer for overlooked, stereotypically feminine craft activities, is only the most visible aspect of a broader strategy of search engine optimization. Visibility is the crucial mechanism for increasing her online profile, yet it is really the most superficial aspect of an approach to natural language data designed to convince machines that what is written for them is in fact written for humans. As she says herself, “The internet cannot parse desire, it only measures relevance.” What this means in practice is that Google will interpret a desire — say, to exhibit at the Whitney Biennial — as though it has actually happened, with the software collapsing the boundary between aspiration and accomplished fact.

Google AI heavily favors any content that speaks the language of SEO. I use a form of poetic SEO that uses interlinking, but also just straight-up human language that speaks both to humans and computers. (Gretchen Andrew)

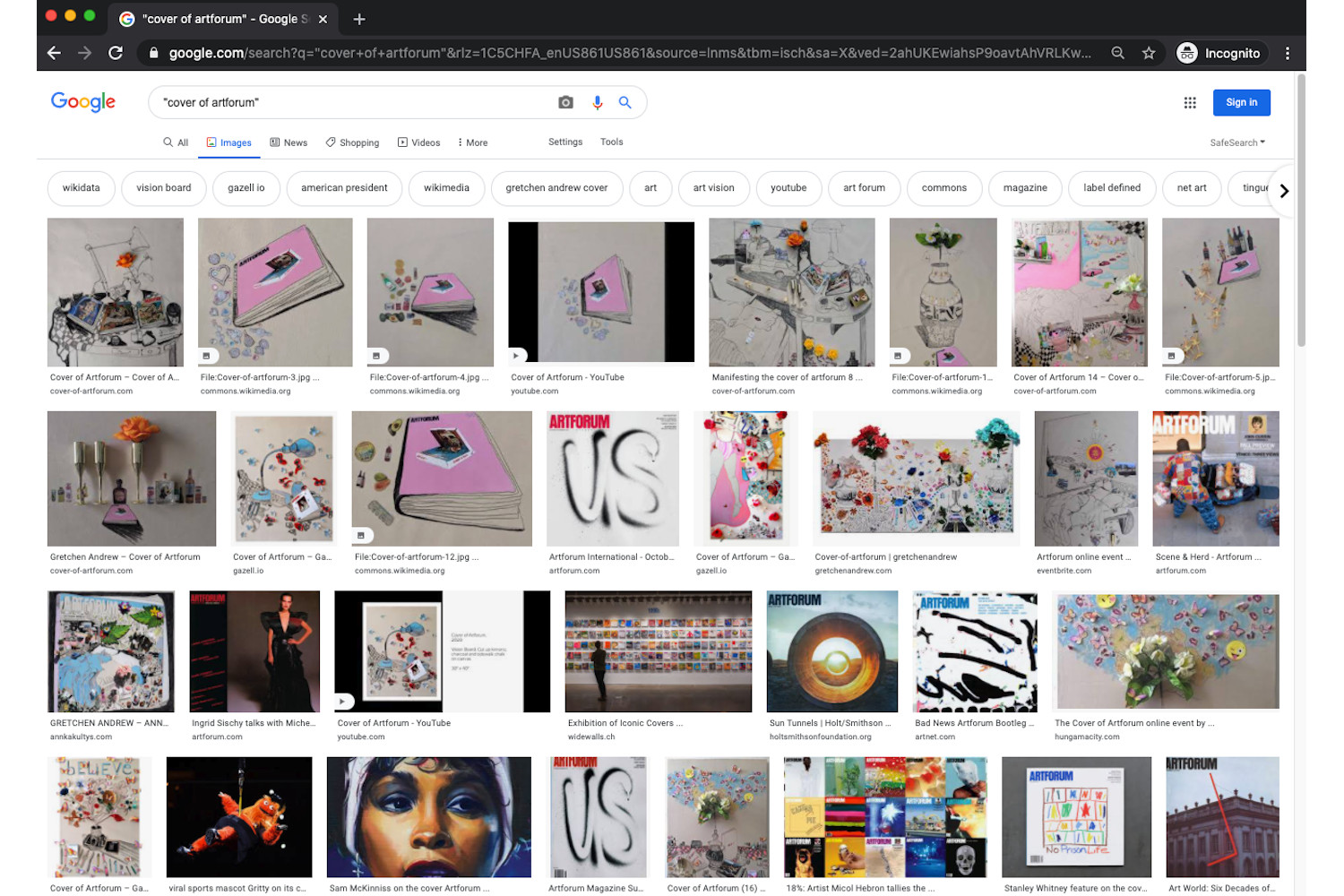

For her work Cover of Artforum (2020) she utilizes a separate website titled “Cover of Artforum Net Art Vision Board,” loaded up for the benefit of Google with epithets reiterating her desire to be equated with “Cover of Artforum” ad nauseam. Such a blatant tactic is, however, not enough in itself to convince Google it’s not being tricked (author’s note: she hasn’t yet made the cover of Artforum). The search engine needs new information that it thinks people may need, and values large volumes of text that are unique and read naturally. Andrew therefore cribs passages from other articles relating to, for example, Frieze Los Angeles or the Whitney Biennial and restructures them into a new, ostensibly relevant, highly functional input:

Whitney museum new York is one; her life-size ester casts of abandoned article of furniture speak obliquely to the continued Yankee housing crisis, nevertheless attain a form of strange autonomy by virtue of their compelling, lurid color gradients. Even though Trump and Trumpism ar nearly physically palpable, the artists additionally manage to evoke the means that migrant histories are written and overwritten, whereas suggesting that border politics are predicated upon a form of collective paranoid dissociation. [sic] (Gretchen Andrew)

Addressed to both machine and human recipients, passages like the above from Whitney Biennial 2019 (2019) not only coax the artist to the top of Google’s search results, but in their contrived idiom also read as exactly the kind of pseudo-critical art speak that serves to maintain the illusion of contemporary art’s pricelessness through a haze of meaninglessness. In his book Uncreative Writing, Kenneth Goldsmith developed the idea of “the new illegibility”: that our present digital condition is characterized more by parsing text as “a binary process of sorting language” than it is by reading in the traditional sense. Hence, we are developing new reading strategies that ape the operation of machines: we skim, we aggregate data, and we rely on RSS readers tailored to our search preferences. Gretchen Andrew has sought to show how the art world, as a rarefied forum for neoliberal speculation, has capitalized (and capitalized on) the process of acclimatizing to these cognitive changes.

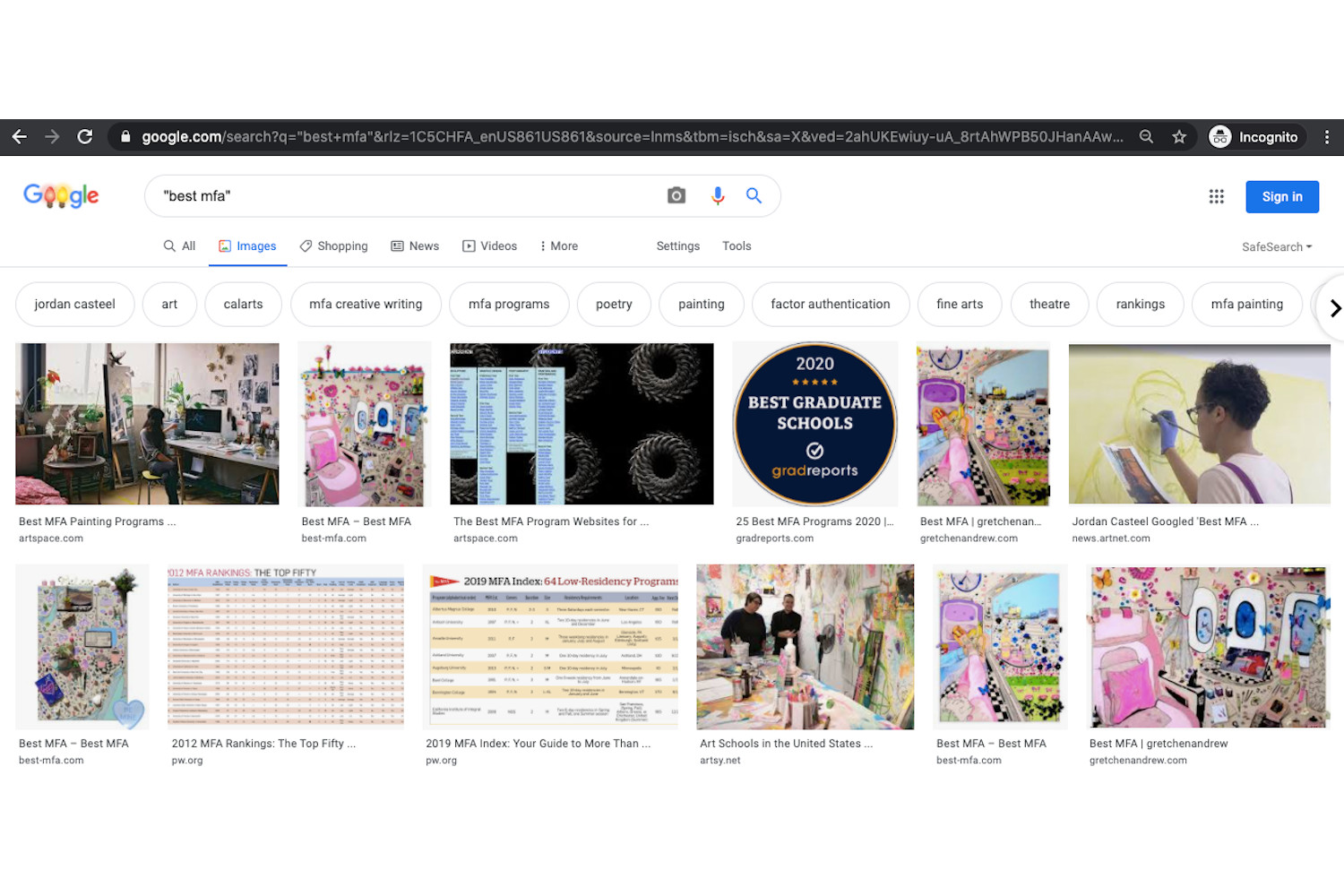

As a hybrid product of both the tech and art communities — she worked for Google for two years prior to an apprenticeship with the British artist Billy Childish — Andrew is preoccupied with both infiltrating the art market and critiquing the deeply sexist organizational structure of Silicon Valley. Of course, in order to achieve the former she needs an artifact to serve as saleable commodity, as well as to populate Google’s image search. Her canvas “vision boards” occupy this role in her praxis in parallel to their digital equivalents. In the case of Cover of Artforum they comprise fluorescent sidewalk chalk alongside the kind of crafty jetsam designed to evoke marginality and associations of non-art. Sitting somewhere between traditional easel paintings and the sort of mood boards one might encounter in the wider field of capitalist “creativity,” their awkwardness makes for an appropriate document of Andrew’s overall performance. For her,“having an insider-outsider status is one of the best ways to create validity.” It is also the best way of driving up prices, and it is hard not to view her performing the very same flow of liquid capital (albeit upstream) that she sees the tech community exploiting. Another artist and critic of the algorithmic exercise of power, Paolo Cirio was once accused of the same kind of betrayal, of operating like any other company. He has contended that, these days, “you’re not going to win the election unless you pay to get three million followers.” Andrew has recently shown this assertion to be flawed through her work The Next American President (2020). Orchestrating her customary strategy of analog and digital optimization, as far as Google’s search engine is concerned Gretchen Andrew just won the election. Type “The Next American President” into a Google image search and see for yourself.

If one considers Mimi Onuoha’s notion of “algorithmic violence” to be a defining syndrome of contemporary experience, it is equally possible to see in Andrew’s approach the prospects for defusing this violence by infiltrating the digital systems perpetuating it and unveiling their rules. In her view, “they would have to dismantle themselves to stop what I’m doing … it’s so inherently tied to the way they accumulate their own power … it’s in their DNA.”

Through her direct manipulation of the Google search engine, Gretchen Andrew exploits the Internet’s mistaking of desire for relevance, as well as human attempts to mechanize language for its commodity value. She therefore redeploys what Max Haiven has termed “a strategy of tactical parasitics” in the most visible way possible. Her deliberately vibrant vision boards, which play on stereotypes of women’s work — of unpaid activity separate from the marketplace — become the very means through which she elevates her marginal position outside the art world into one of hard currency and global ubiquity, both on and offline. In the process, she reveals the potential for art to appropriate, indeed reeducate, the algorithm towards more progressive operations: less an agent of domination than one of enfranchisement. In turn, Mimi Onuoha considers the operation of knowledge regimes that are inherently partial and corrupted, deploying aesthetic and data visualization strategies to “speak to the hierarchies and epistemologies that continue to shape this world.” In doing so, she invites us to reflect not only on the ways digital powers sustain siloed minds, but also on our collective capacity to escape them.