In Josef Strau’s production one glimpses, in filigree, a laborious and jittery tectonic adjustment, a balancing act between — to use the terminology of a fellow citizen dear to the artist — superego and id. At times the imposing silhouette of the former prevails, emerging via frequent references to titans of twentieth-century cultural production, an almost palpable search for high achievements. Yet this is always muted, in his interviews, with self-deprecating irony, modesty, or simply a soft evasiveness that reveals his self-diagnosed profound “bad conscience,” to put it in Nietzschean terms. Mostly the latter prevails, allowing the powerful flow of utterances to address what feels like a vivid, genuine individual necessity.

As is well known, writing provides a center of gravity for Strau’s practice — a kind of writing rooted in the history of German literature. His self-narrative, even if it feels contemporary (references to brands, disruption of the linear “fabula,” licenses with linguistic conventions), appear to derive from literary genres, for instance the autobiographical confession cultivated in the Pietist spiritual renewal movement of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which eventually evolved into the German literary novel… Strau enacts a dry, but wavering, writing that expectorates mundane preoccupations and ordinary facts. When it does not linger in a noirish mode, it unveils a completely expressive repetition, rearrangement, flourishing, and exhaustion of stylistic elements. These elements have evolved by minimal increments over a scale of years. An understanding of their aesthetic and functional value, of their implicit theoretical position, arises by immersion, through patterns of recognition following the dense ramifications of the “plots.”

In this generous retrospective at Kunstverein Düsseldorf, textuality is expressed not only in the posters, in which it arranges itself in visual blocks, but also for example in the cardboard-and-tape structures. The outsides of these small transitory cinemas showing videos made by friends inspired by his texts — Keren Cytter, Bernadette Van-Huy, and Enzo Shalom — bear alphabetical letterforms, but also constitute a structural foundation for the exhibition itself. The narrative here is again autobiographical, as the nomadic artist was urged for the first time not to devise an exhibition from scratch, but to rethink his own past production and arrange it in the galleries. This challenge led him to such solutions as displaying the boxes that contained the works that arrived in the city of Rhine-North Westphalia as a bridge to the past. Another example is the newest work, The 13 Hour Cymbal Spiderclock that Exhales the Dreams (2020), a sound-producing sculptural group that heralds a new messianic time, a breakthrough toward the future.

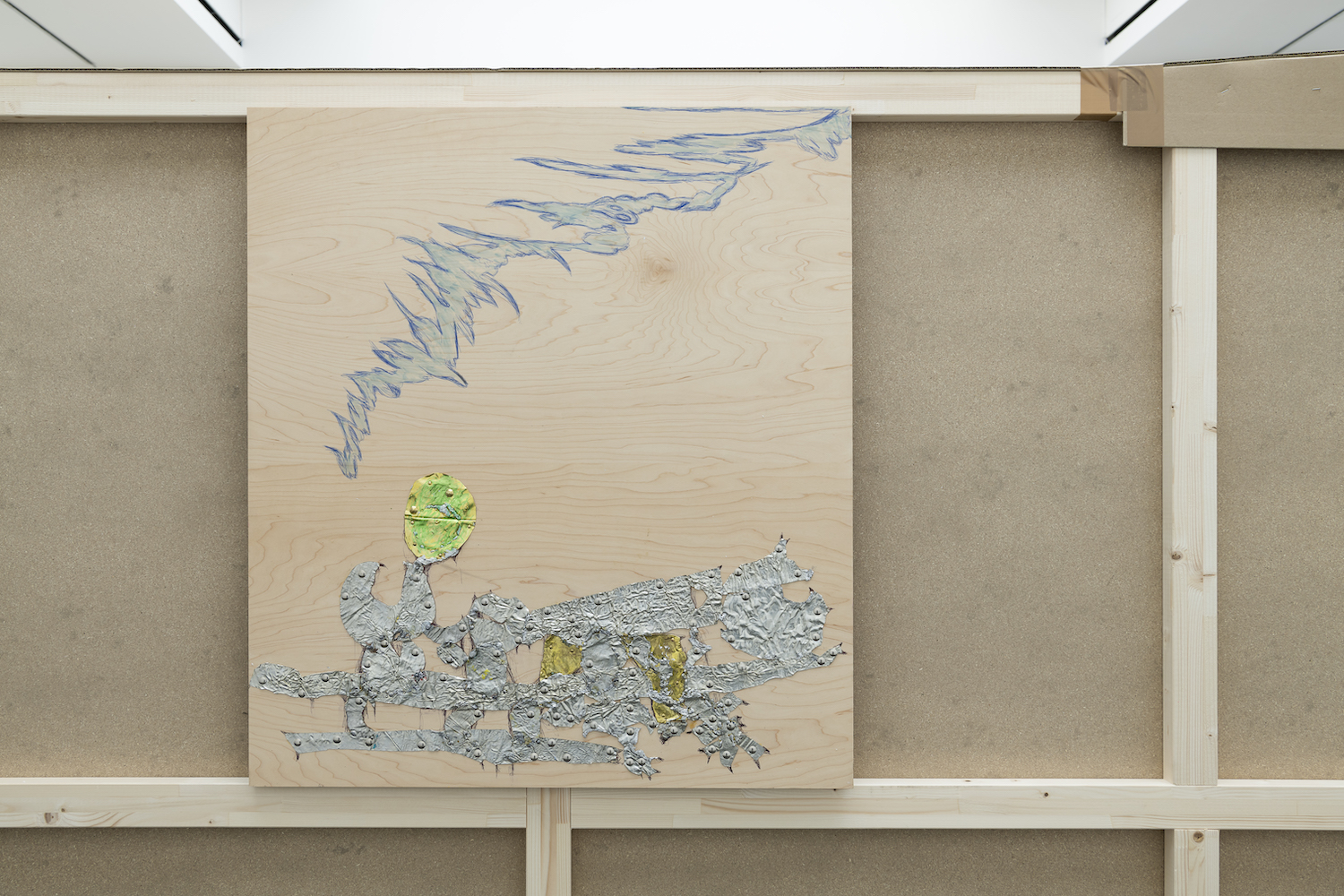

Between these: appropriated, untitled images of the night sky that appeared in his first, untitled solo show at Galerie Christian Nagel, Cologne, in 1991; a wide selection of his tin-on-canvas wall works; oh so many lamps; seductive prints; a fragile paper teapot; and, finally, Healed Turtle from Vienna (2020), the sculpture of a turtle from his 2015 show at Secession, restored after minor damage and presented as new on a pillar. This is an exhibition put together with a secure command of the space and a graceful sense of display (we can imagine it’s just the tip of the iceberg), featuring the output and documenting the peregrinations — as a visual biopic — of one of the most precious and unique voices operating in contemporary art today.