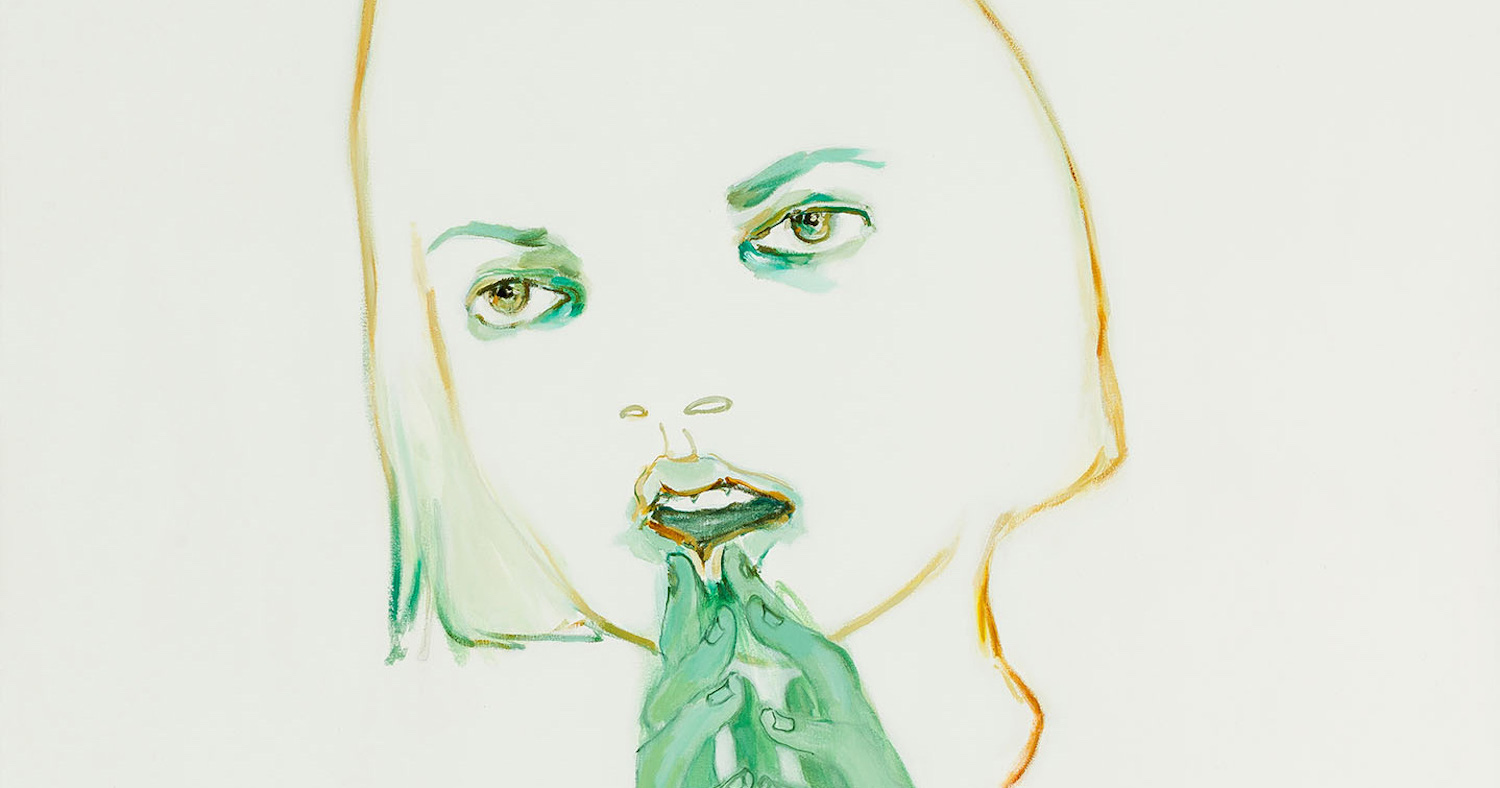

The title of Olivia Erlanger’s exhibition at London’s Soft Opening — “Home is a Body” — brings to mind Louise Bourgeois’ “Femme Maison” series, in which the artist depicted the female form as being conflated with the architecture of the home. In her painting from 1947, the domestic environment is rendered as an interchangeable anthropomorphic surrogate, with the shape of a house or apartment building in place of where a head or torso might be found.

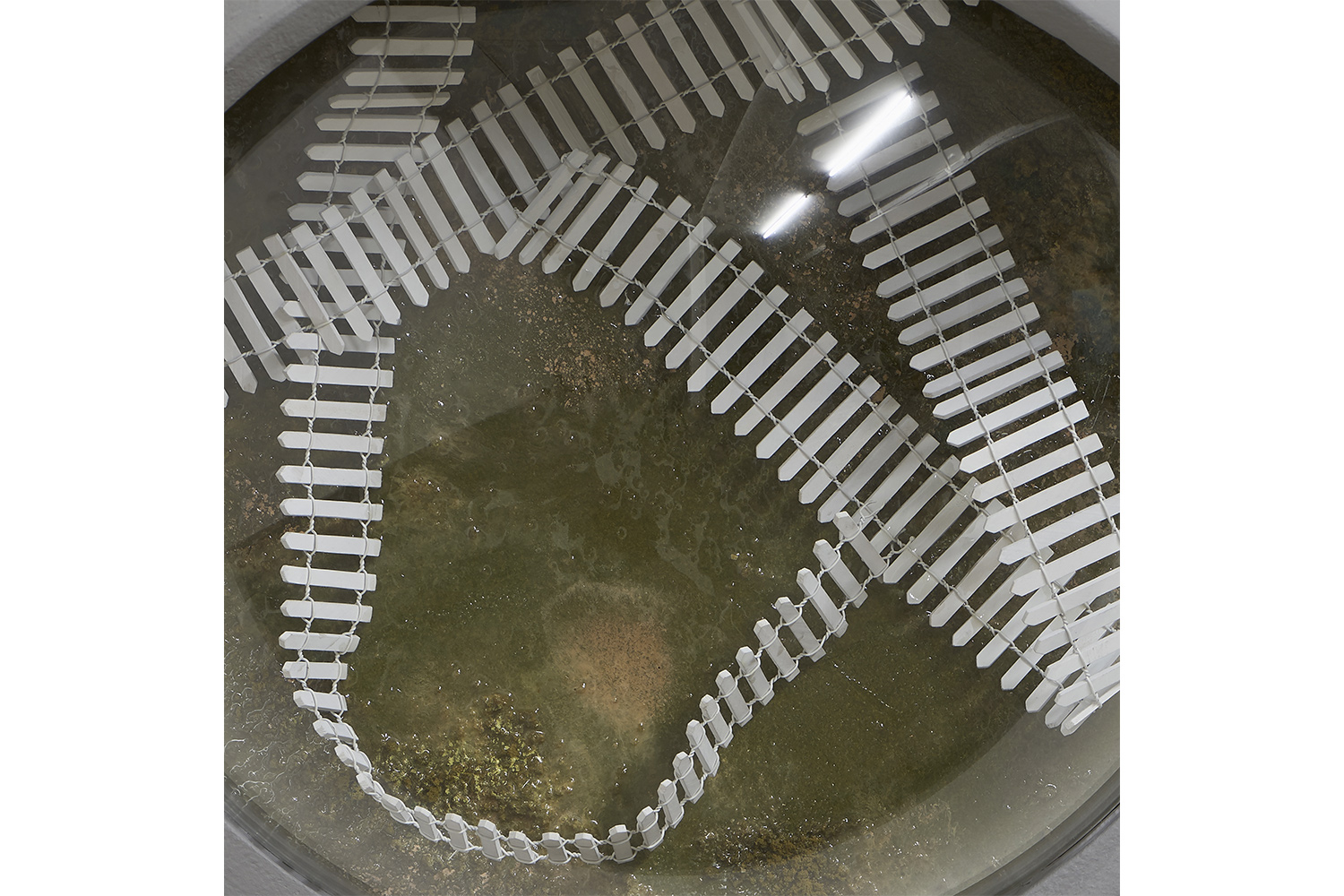

Erlanger’s heart-shaped fence sculpture, Wyndcliffe (2020), conveys a similar symbolic presence. The iconography is romantic, even cute. However, the coldness of the aluminum material, with the point of each picket sharpened like the tip of a knife, indicates a more sinister analysis. Akin to the work of Bourgeois, this demarcated area of refuge, even love, instead becomes a location of confinement or alienation. Interested in the mythology surrounding ‘the American Dream’, the aesthetic of suburbia — from the distinctive picket fences to flat-pack homes, garages, and laundromats — has occupied much of Erlanger’s practice, often depicting the urban landscape as a space of isolation or estrangement. Earlier this year, in Los Angeles, she presented a trio of snow-globe sculptures, the miniature houses inside trapped and siloed from the rest of the world.

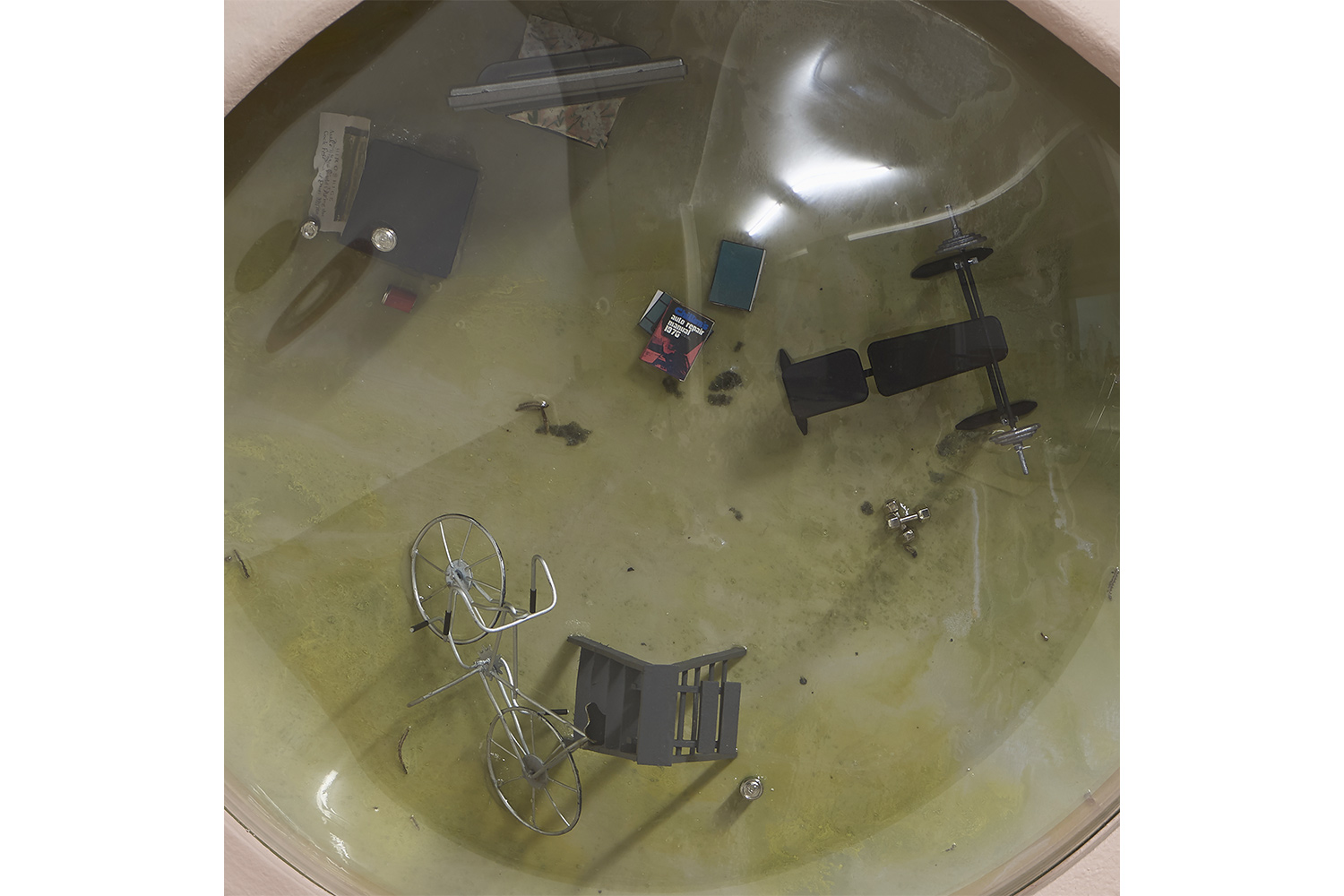

The other five works in the show, each titled after a different time of day — 11:34 AM; 3:07 PM; 5:13 PM; 8:41 PM; 12:21 AM (all 2020) —all take the same form. A dollhouse-like room, complete with a selection of miniature furniture and objects, encased by a clear, plexiglass dome, set within a frame shaped like a large eye. When compressed, this concept of “home is a body” is also suggestive of the word “homebody,” an individual who prefers to stay indoors rather than venture out. However, in this case, all the ‘home bodies’ are absent, only able to be represented metonymically through a selection of specific possessions. Erlanger’s attention to detail is exacting, and each item is discernible despite its scale. The objects are additionally listed in the materials section of the work’s captions, configured as a litany of stuff. Across all the rooms, these include: Mac desktop, pink MacBook, white fender, bench press, dumbbell, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Evian, bicycle, armchair, knockoff Noguchi table, dirty laundry, cactus, books, posters, among other things. There is a sense of accessibility. The items are both familiar (the quintessential rubber duck in the bathroom) and topical (the keyboard balanced on a paint box perhaps indicative of a makeshift home office). Their proximity to current trends — the ‘millennial pink’ computer, succulents, a particular design aesthetic — allows the potential inhabitants of the space to become an amorphous being rather than a singular individual, in addition to questioning how identity and personal taste is actually led and shaped by consumerism and market influences.

Although the interior of each environment is unique, the serial nature of their exterior can be analyzed through ideas of modularity and mass production, notions which are also commonplace within the history of post-war suburban architecture and town planning. In the introduction to The Infinite Line (2004), the art historian Briony Fer writes of repetition: “It is a means of organizing the world … of disordering and undoing … utopian or dystopian … animating and transforming the most everyday and routine habits of looking.” In her text “Endless Days,” commissioned to accompany the exhibition, Orit Gat perceives Erlanger’s constructions as akin to surveillance cameras. This concept of CCTV perhaps supports a far more dystopian interpretation of Fer’s “everyday and routine habits of looking”: the sinister observance of the state. Like a voyeur, the viewer is free to peek in unobserved, but there is not much pleasure to be derived from this snooping. Rather, the home is packaged as a product, a timestamp, an extract of an abstract existence, with the potential for replication.