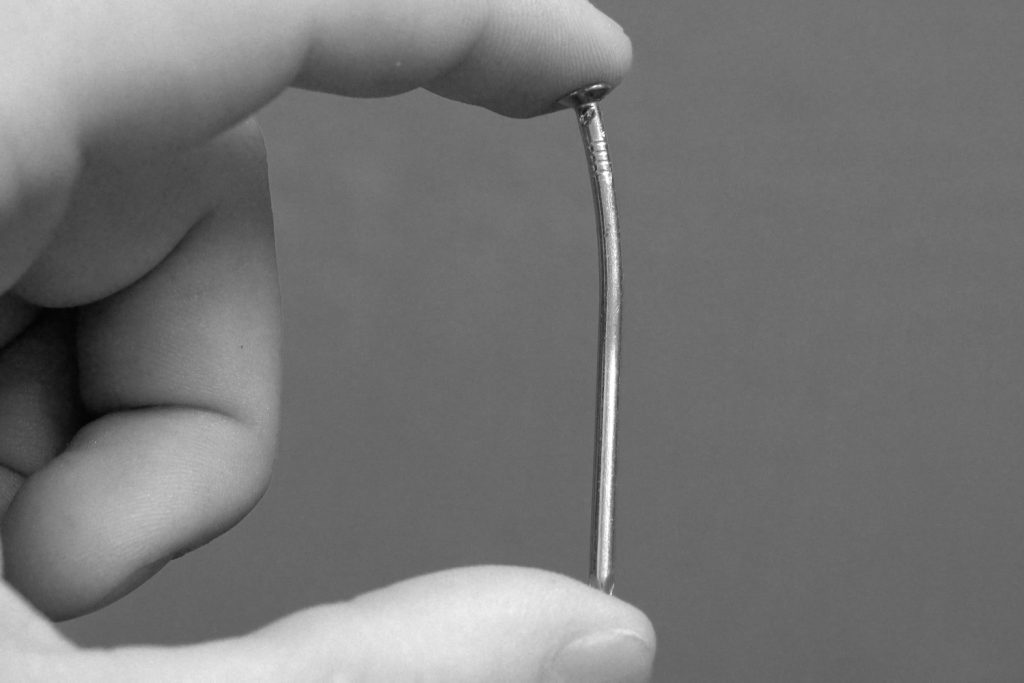

A pole, jutting horizontally out of a wall, inscribed with the word HIT, is recognizably the handle of a shopping cart from the eponymous small-scale supermarket chain. According to the artist, Andrzej Steinbach, the object was found in the vicinity of a violent demonstration, where it had been converted to a baton. It is part of a large group exhibition on the effects of gentrification, organized by the Art’Us Collector’s Collective, who invited young Berlin artist Paul Hutchinson to curate from their collections. The show combines established artists such as Kader Attia, Sabine Hornig, and Peggy Buth with younger names like Susa Templin, Sophia Süßmilch, and Harry Hachmeister. It’s not without irony that an exhibition about this subject is presented in, of all places, a vacant office space owned by the company of one of the collectors.

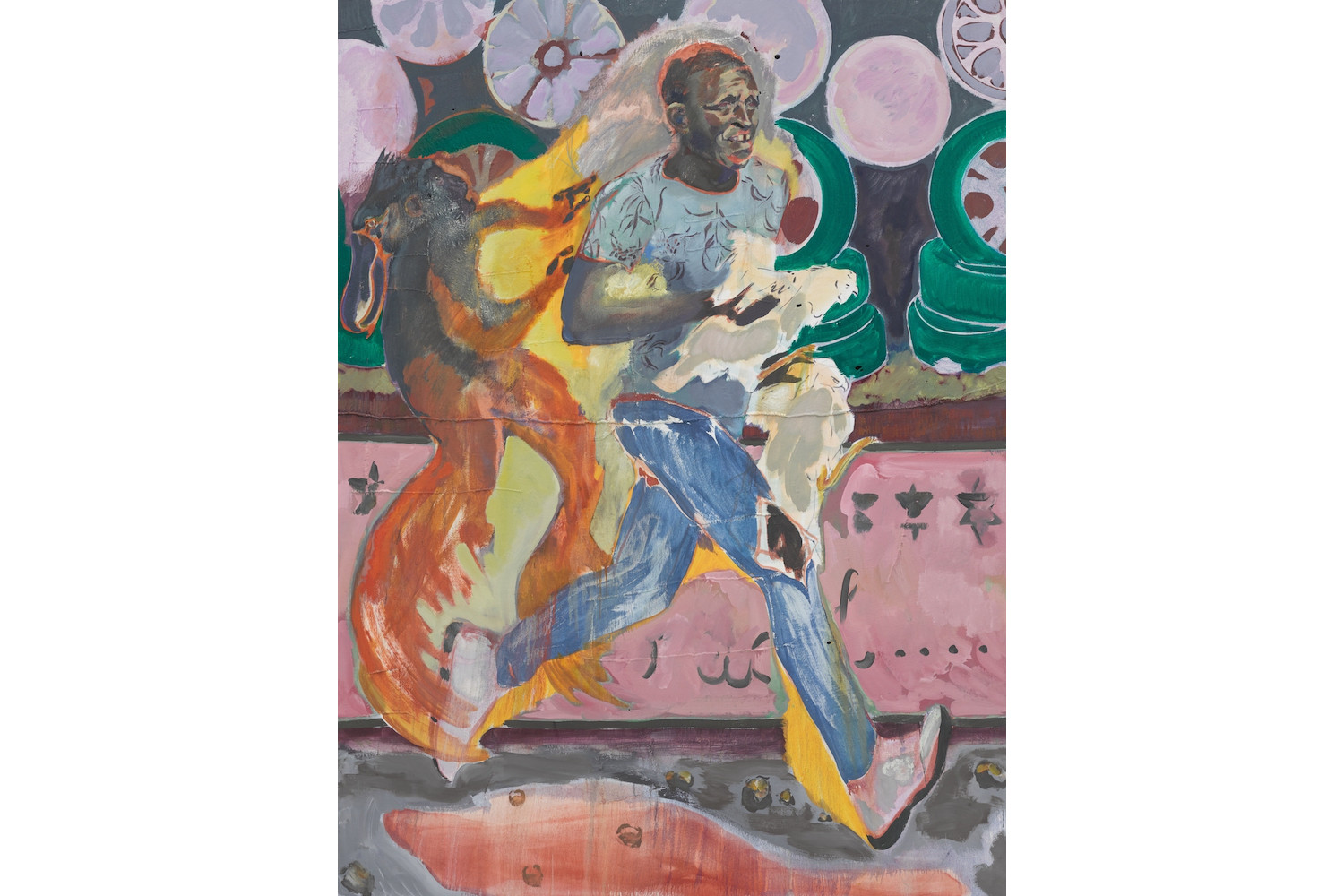

The project is part of “Various Others,” which kicks off the art season in wonderful, hedonistic Munich. The program aims to showcase not only larger local galleries but also younger ones, artist-run spaces, and private collector initiatives. Exhibitions are accompanied by events at high-profile public institutions, including Michael Armitage and Franz Erhard Walther at Haus der Kunst; Thierry Geoffrey’s unsettling emergency workout at Villa Stuck; and, paling a little in comparison, Lucy McKenzie’s retrospective at Museum Brandhorst, to mention just a few. Most spaces involved have for the occasion partnered up with galleries from Berlin, London, New York, and others as far away as Bengaluru.

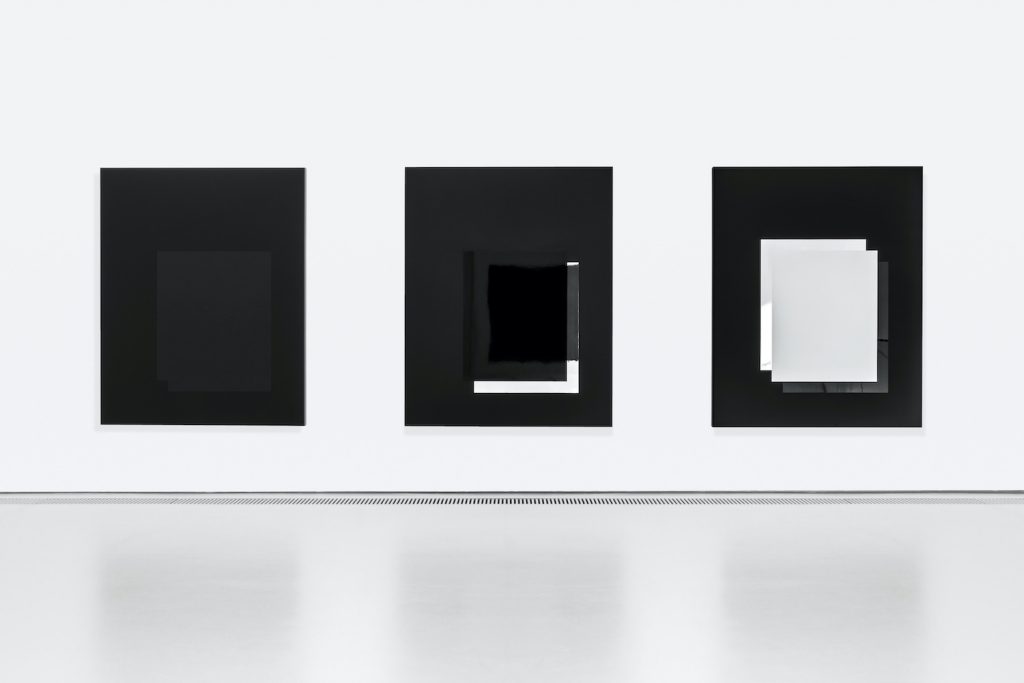

Yes, Bengaluru! At veteran nonprofit space Kunstraum München one can see “Responsive Curating” in practice, a show of instruction-based art that aspires to get along without any costs for artist travel or artwork transportation. Kunstraum director Ralf Homann explains that this was achieved by realizing works only with what is locally available, thereby turning the logic of the art market on its head. In reality, the curators faced many problems: while it was cheap to commission local craftsmen for the production of artworks in the show’s initial venue in Bangalore, in Munich this was too pricey, so the curators had to build the works themselves or ask artist friends for help. Even if one sculpture couldn’t be realized, the project is a success, raising fundamental questions about art-world logistics. Afterward, one may well look at artworks in galleries with a different eye: What was the cost in terms of labor, resources, and pollution generated to bring this work here? Was it worth it? The exhibition has an immediate effect when viewing larger productions in established galleries, as when Rüdiger Schöttle Galerie partners up with Berlin’s König Galerie, showing ceramics by Michael Sailstorfer, an artist who graduated from Munich’s Academy of Fine Arts; or Galerie Walter Storms with its large, beautiful loft filled with works by Gerold Miller and Katja Strunz; or sculptures by Gabriel Kuri, courtesy of Esther Schipper, Berlin. It’s a lot of formalism and, ultimately, a lot of stuff.

It’s more entertaining on the other end of the scale. The newest artist-run space in town, fructa space, features a solo exhibition by Andrzej Steinbach, mentioned earlier. In the most striking work he shows off his photographic skill, arranging a female construction worker in the pose of Alexander Rodchenko’s famous photograph of poet Vladimir Mayakosky. The work, more than just a quip on constructivism in general, addresses conventions for depicting gender and genius.

Munich’s youngest professional gallery, Nir Altmann, just moved to the working-class district of Giesing. Collaborating with Peres Projects and Galerie Sultana from Berlin and Paris, he paired works by hip newcomers Paul Maheke and Rebecca Ackroyd with Ndayé Kouagou’s fabulous collages in resin — refreshingly subversive reflections on success and failure.

These sentiments resonate well with a concurrent show at the local Kunstverein. “Not Working: Artistic Production and Matters of Class” features the seldom-seen work of Annette Wehrmann, specifically her self-made alternative currency of concrete shells alongside an audio recording of the artist trying to convince passersby to acquire some for real money. Parallel to this, the archive has been made accessible in preparation for the Kunstverein’s bicentennial, giving viewers a chance to unearth material related to historic exhibitions and providing a glimpse into Munich’s underrepresented art scene and its long history of leftist activism.