The single letter “s” provides a compelling indicator of this exhibition’s character and significance. It appears in parentheses at the end of the show’s title: “ecofeminism(s).” Plurality prevails among the sixteen artists included in the show. Their diverse offerings of theme, style, medium, aesthetic, and attitude testify to the imaginative territories unleashed when artists are fortified by ecology and feminism.

The show’s significance far exceeds a survey of a fertile facet of recent art history. That is because the exhibition opened in the throes of the COVID-19 crisis. The imposition of extreme disruptions due to virus-induced protocols has demonstrated that radical adjustments are inevitable in all aspects of work and play. The quest for causes and solutions spurred by the virus are not merely medical. It includes feminism because COVID exacerbates gender and social inequities. Likewise, it includes ecology because pandemics are linked to pollution and habitat loss. As a result, this timely exhibition provides an opportunity to review the social condition that gave rise to feminism, as well as the environmental disruptions attended to by ecology. Furthermore, the pandemic may be preparing the public to adopt the resilient, equitable, and sustainable strategies these artists have long advocated.

The lower case “e” in the title provides insight into the curatorial premise of this exhibition. Monika Fabijanska, the exhibition curator, employed this linguistic device to acknowledge that the term “ecofeminism” may be too disparate to merit capitalizing as an art movement. This strategy removed the obligation to construct a tidy thesis. Fabijanska accommodated the absence of unifying specifics by providing a generalized definition. She stated that ecofeminism “insists that everything is connected — that nature does not discriminate between soul and matter.” This show offers a rich sampling of the creative outcomes of such “insisting.” Although no male artists are named on the checklist, the gender implications of the exhibition and the following comments bypass sexuality and focus on attitudes available to everyone.

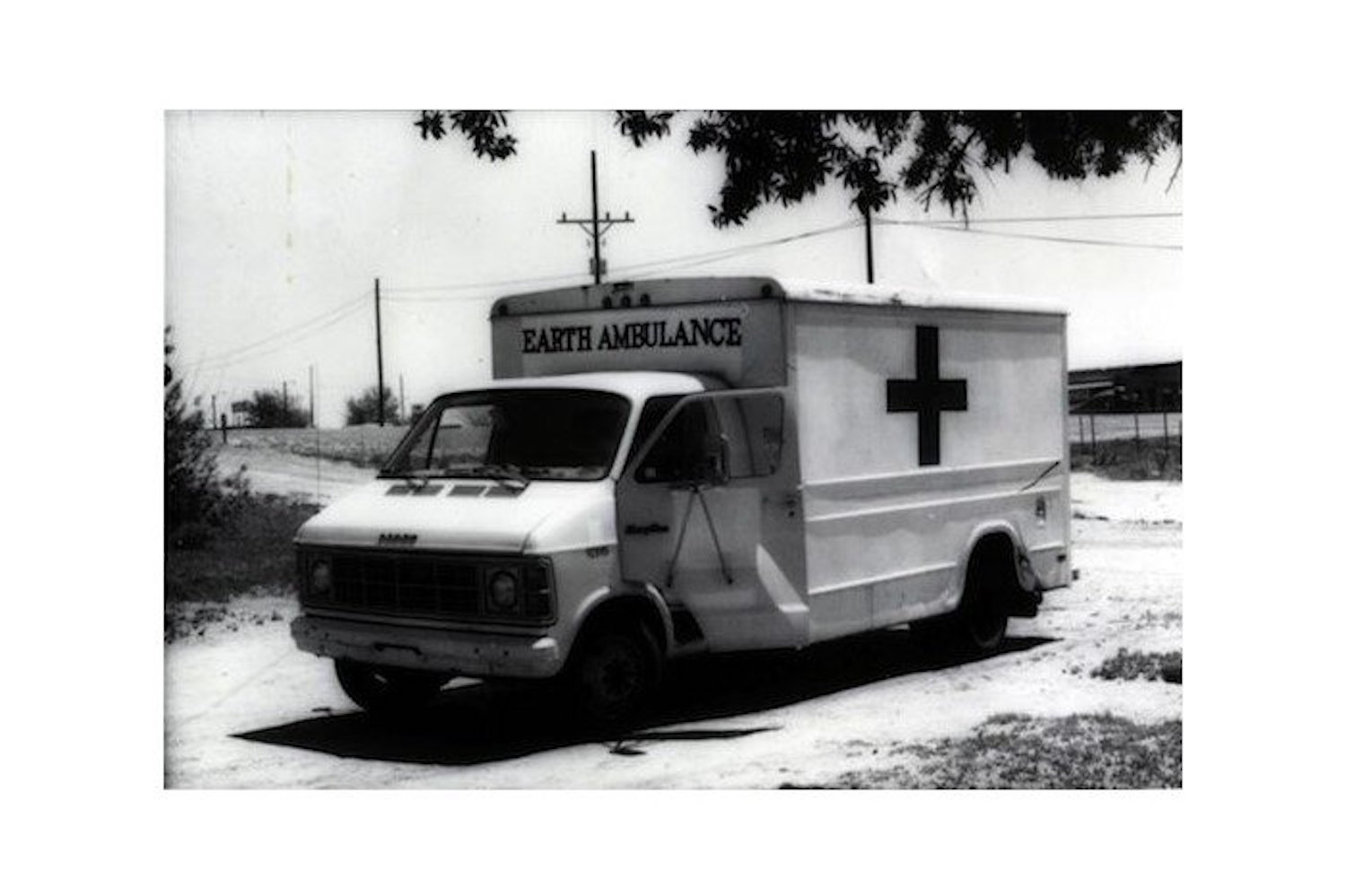

Helène Aylon created a compelling ecofeminist critique of humanity’s epic expedition on earth. She enlisted thirteen women to heal a loved one. Women have long been associated with such tender “performance ceremonials.” She assigns this feminist practice to an ecological theme. The loved one receiving these ministrations is soil sickened by nuclear contamination. The fact that all the participants were female suggests that responsibility for the abuse of land and the abuse of women belongs to the entrenched patriarchal framework of ownership and domination (The Earth Ambulance, 1982).

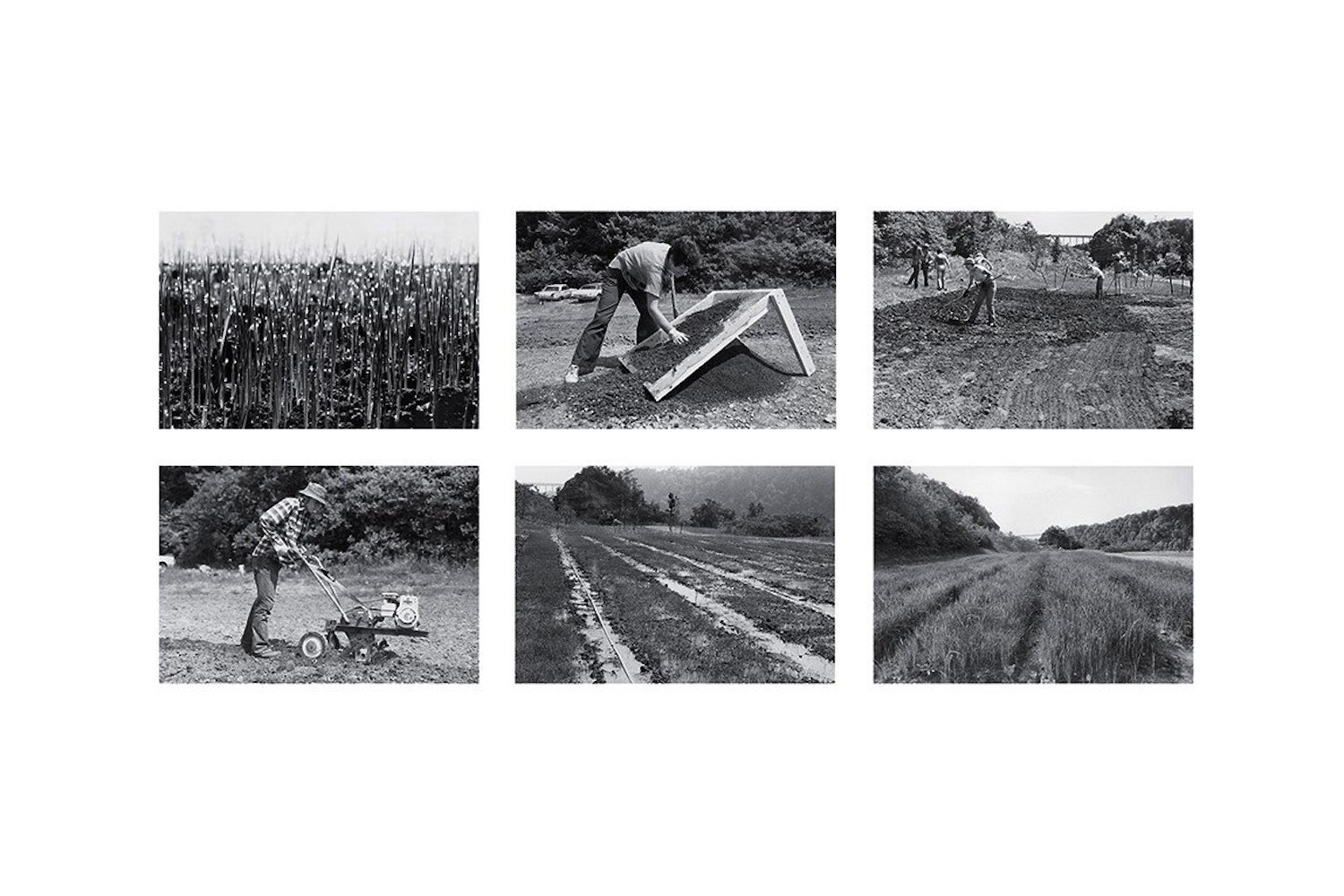

Likewise, Aviva Rahmani invites people to participate in the water cycle, a key ecological principle. Rahmani crafted a precise set of instructions in which people enact a version of a water cycle that may not appear in textbooks. They fill a plastic bag with water and then board automobiles to link domesticated water that is collected and treated to serve human needs, to waters of the vast, untamable oceans (Physical Education, 1973).

Hanae Utamura conducts modest repetitive gestures within the grandeur of such outdoor settings as the Sahara Desert. Her gentle restraint delivers a revolutionary message because it reverses the dominance, control, and authority that many feminists associate with Eurocentric capitalist patriarchal culture. The radical political implications of her actions are accentuated by the interactions she chooses to conduct. Utamura wipes, waters, and scrubs, aspects of traditional women’s work, in a manner designed to leave no mark on the land. However, these silent rituals conducted during her sojourn in the desert are imprinted deeply into her spirit (Secret Performance Series, 2010–13).

Mary Mattingly’s contribution to this exhibition reveals feminism’s distrust of ego-centrism and ecology’s belief in eco-centrism. She dismissed individualism and replaced it with communalism. The former rules modern behavior and enjoys legal protection. The latter is common among tribal cultures and is maintained through custom. Mattingly factored communalism into the survival strategies she developed to attend to the environmental collapse wrought by climate change. Her schemes for deriving nourishment, generating electricity, managing waste, and creating shelter are all envisioned as communal efforts. This multi-year social experiment is conducted aboard a floating barge (Swale, 2017).

Betsy Damon inverts the assumption that elemental components provide the most accurate and reliable indicators of complex phenomena. She substitutes an ecofeminist strategy for acquiring truth. Instead of reducing a subject to distinct, separable, and independent components, she engages the messy complexity of ecosystem functions that ecologists engage. The artwork replaces “reductionism” with “holism.” A river provides the subject of the artwork in this exhibition. It is presented in the form of a 250-foot casting of a dry riverbed. Because the casting technique produces a direct imprint of the quantity and distribution of every element, the river is known to us by evidence of an accumulation of stones, gravel, soil, shells, etc. Unmediated by interpretation or observation, this artwork conveys a complex and inclusive aspect of “truth” as it is practiced by ecologists but shunned by the scientific establishment.

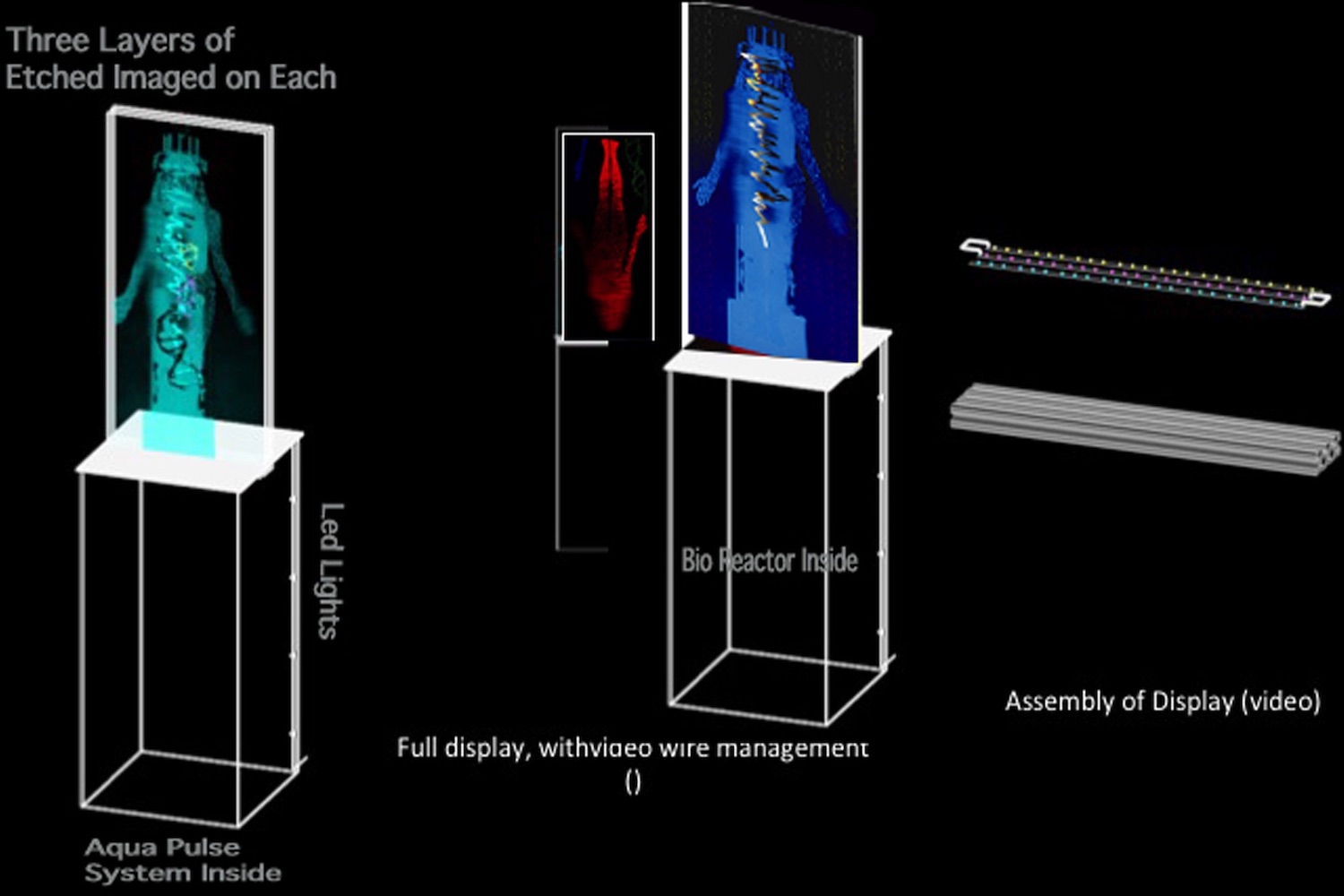

Other artworks confirm the importance of the letter “s” in the exhibition title: Carla Maldonado addresses binary opposition; Ana Mendieta enacts earth-based spirituality; Eliza Evans recruits the public to sabotage corporate claims of mineral rights; Andrea Bowers memorializes past politically inspired environmental protests; and Lynn Hershman Leeson constructs a revolutionary off-the-grid water filter that kills bacteria and degrades plastic.

These examples testify to the bold experimentation being conducted within the framework of ecofeminism, despite the fact that it lacks a succinct definition of itself. What is certain is that both ecology and feminism contrast the dominant narrative in technologized societies. The same entries that have been referenced in this essay appear in their respective handbooks of behaviors, but they represent standards to master in one, and hazards to avoid in the other. One comes away from this exhibition with eager anticipation of scenarios that ecofeminism promises to generate in the future.