Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

Mark Twain said that “there is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations.” I used this quote to form the basis of an article I wrote last year reflecting on my experience of Aerowaves’ Spring Forward festival in Paris, which explored the notion that, “while the title ‘contemporary dance’ by nature seeks to be modern and original, one cannot deny that the medium’s history influences the way we see dance, and in fact create it, in the twenty-first century.” Little did I know that Twain’s words would yet again occupy my mind when reflecting on Spring Forward 2020, an edition of the festival that, due to an unprecedented global crisis, brought together the pre-corona work of twenty international dance artists and presented it in the new “curious combination” of an online dance festival.

Taking place in a different European city every April, Spring Forward is a three-day festival providing a platform for Europe’s most vibrant and promising choreographers. Presenting twenty works that are selected annually by the Aerowaves network — which currently has partners in thirty-three countries — the festival also seeks to contribute to the development of quality dance criticism through its accompanying writing program, Springback Academy. I was lucky enough to take part in this scheme in 2019, and since then I have felt privileged to be part of the Aerowaves family, contributing to Springback Magazine, receiving mentorship from critics from The Guardian, The New York Times, The Times, and The Scotsman, and making connections with other emerging dance writers and critical thinkers from across the continent. Being able to stay in touch with this network throughout the year, whether it be through social media or in person at other events supported by Aerowaves, has been a great source of inspiration and motivation for me as a writer, and created a strong sense of pan-European community that has been important for me personally as a Brit living abroad in the wake of Brexit.

While I was looking forward to reconnecting with everyone in Rijeka, Croatia, this April for the 2020 edition of Spring Forward, COVID-19 had other ideas. As the virus spread around the globe and restrictions on travel and large gatherings began to be put in place, the Spring Forward team quickly had to make a decision about how to proceed. They eventually arrived at the solution, and mammoth challenge, of transporting the festival online. “We worked night and day for five weeks, and we loved it. We were jointly discovering and inventing day by day,” says John Ashford CBE, the founder and director of Aerowaves. Inventively titled “The Show Must Go On-Line,” the nine-hundred-minute-long Zoom webinar sought to replicate the structure of Spring Forward, requiring participants to register via a Google form before they were able to follow a tightly run schedule of recorded performances, as well as video interludes offering guided tours of Rijeka’s locked-down streets with virtual host Edvin Liveric from the Croatian Cultural Centre. “If we had streamed it on Facebook and YouTube, it would not have been as special,” says Ashford. “It was the ticket at the door, the first step on a journey through the whole program that we had re-imagined for the screen, that helped to concentrate people’s minds.”

Aerowaves is used to presenting dance performances online, having livestreamed the Spring Forward festival since 2015. One of the biggest challenges of the online festival, however, was making it interactive. After much research and brainstorming, the team settled on setting up a chat room called The Foyer — which has outlived the festival — where participants could discuss the shows they’d just seen. There were also post-show artist talks hosted by Springback writers such as myself, in which audience members could appear on screen to ask their own questions. According to Jordi Ribot Thunnissen — an Amsterdam-based dance writer, lecturer, and choreographer, and a fellow Springback writer — “in the face of the loss of shared presence, the Q&A in this format proved to be as valuable as the screenings of the pieces themselves. I often question the added value of a conventional Q&A with the artist exiting a dance-performance, but in this case the shared, moderated conversations added an original and necessary layer to it all. It put the live into the livestream, so to speak.” Enya Belak Gupta, Aerowaves’ video producer and the technical mastermind behind the online festival, was also surprised by how well the closing online dance party — where everyone could appear online and boogie to the music of Balkan hip-hop band Dubioza Kolektiv — was received. “I didn’t realize people would want to party all night long! It felt like a great success and achievement to bring the European dance community together at such a critical moment. Although Zoom or any other digital platform can’t replace physical interactions in person, we all oddly felt connected.”

But the social aspect of the festival was not the only difficult element to re-create. While streaming the prerecorded performances may have been one of the most straightforward parts of the festival — especially in comparison to coordinating writers and artists from all over the world to appear on screen at the right time for post-show talks! — it is arguably impossible to capture the magic of live performance online. “Depth, scale, light, sound, sensory effect — everything is different,” says Sanjoy Roy, Guardian dance critic and editor of Springback Magazine. “It’s edited, removing the viewer’s choice. Then there is the context of viewing — maybe it’s in a kitchen, maybe you have other windows open on your screen or your phone is pinging notifications, maybe your WiFi is laggy. It’s not an auditorium.”

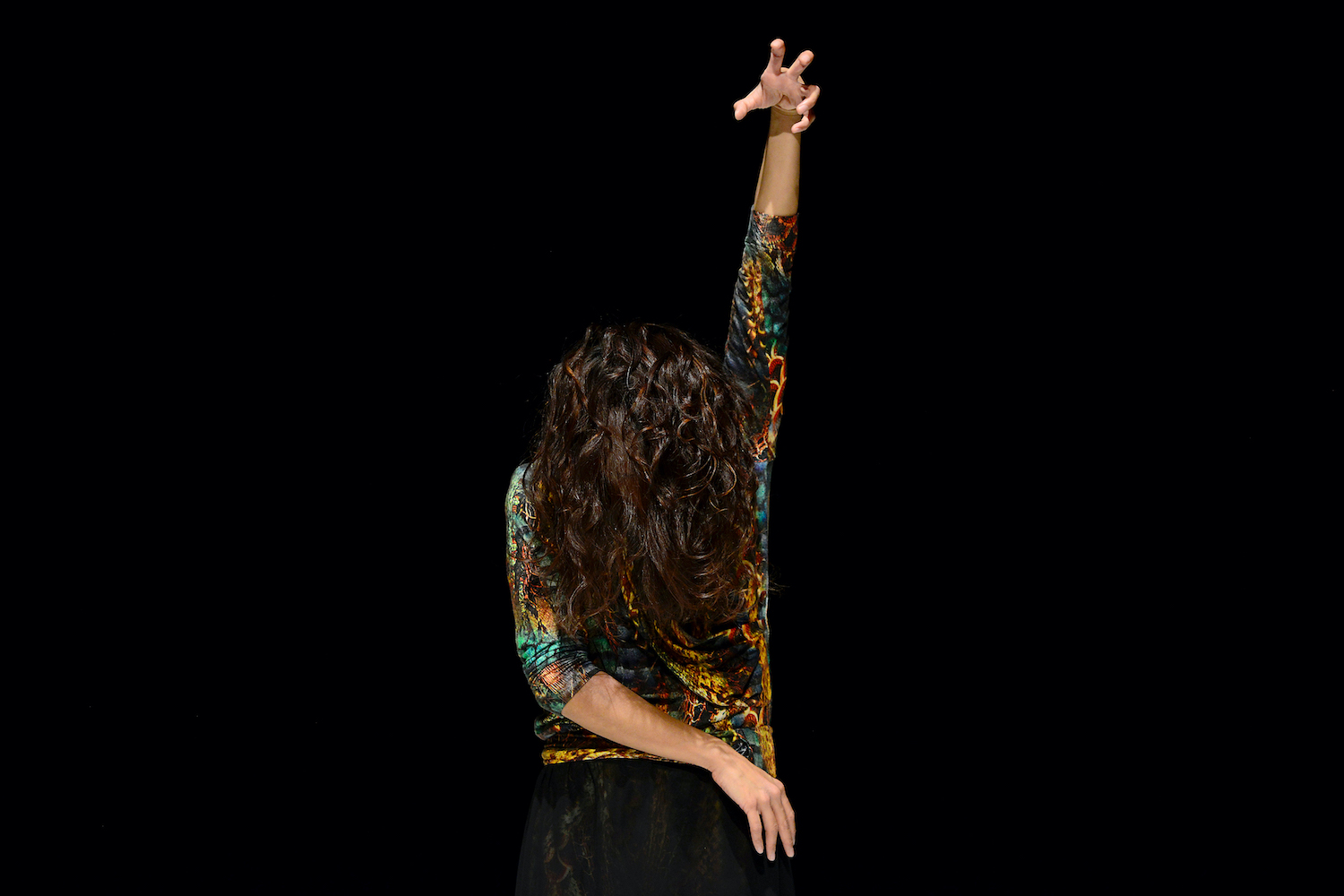

The experience differed for those presenting their work, as well as for the audience. “In the beginning it was quite strange to be observed by so many people at the same time without seeing or feeling them,” says Joy Alpuerto Ritter, the performer and choreographer of Babae, one of the festival’s twenty works. Inspired by Mary Wigman’s seminal Witch Dance from 1926, Babae is a hypnotic exploration of how different movement languages and cultures — including Philippine folk and classical dance, hip-hop, and voguing — can be brought together to reimagine what it means to summon the power of a female dancer as a witch. “I feel that the audience is normally very engaged when I perform this work. There are little moments of humor and physical transformation that give the work a mystical atmosphere,” says Ritter. “The audience are part of this ritual and they are my witness. Of course it’s not the same when watching it through a screen. But at least audiences were able to get a sense of the work. It opened up an amazing network for me.”

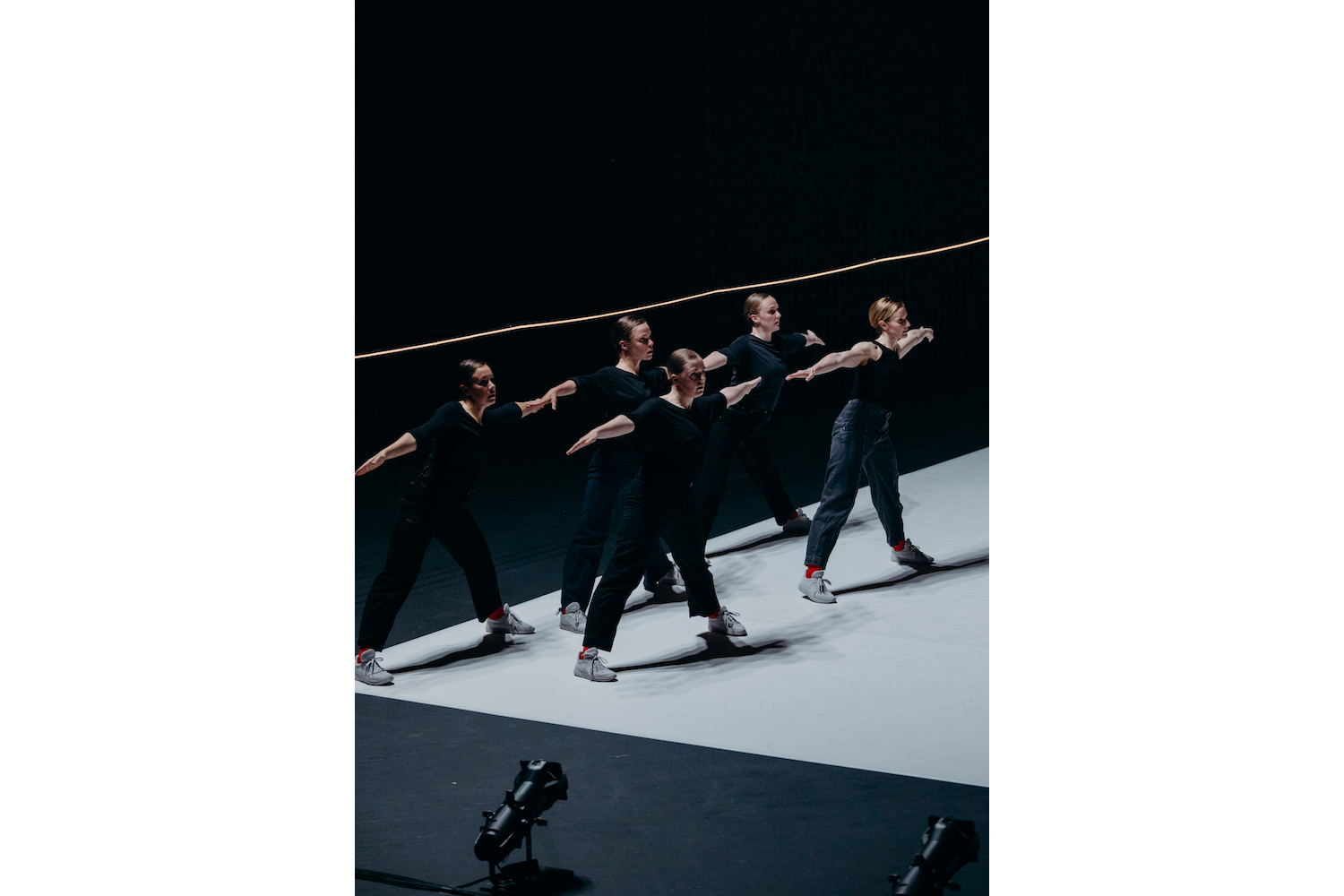

The online format was also challenging for Norwegian choreographer Ines Belli, whose practice is deeply concerned with the spatiotemporal, embodied aspects of dance. “In Postmodern Cool” — Belli’s work which explored how the aesthetics of jazz dance could be reimagined for the twenty-first century — “I worked very explicitly in trying to create a pulsating and intensely concentrated and compact dramaturgy,” says Belli. “I also worked a lot with choreographing the gaze of the audience with its own dramaturgy and intensity. These are things that I think do not translate well on screen.” To account for this, Spring Forward clearly stated to its audiences on registration that all the dance videos that were shown were made for documentary purposes, and were not to be seen as replacements for the live works or “screendance,” which is an art form in its own right. For this reason, “this was never going to be an event for an audience unfamiliar with contemporary dance, whereas the live festival might have been,” says Ashford. However, the online format did mean that an increased amount of people were able to take part, “as it brought the festival to places and people it might not have reached,” says Ribot Thunnissen. In total, around six hundred people from all across the world watched the online webinar each day, many of whom stayed for the full three days of the festival. “The positive effect this had on the environment” — due to the reduction of air miles traveled — “also mustn’t go unmentioned,” he adds.

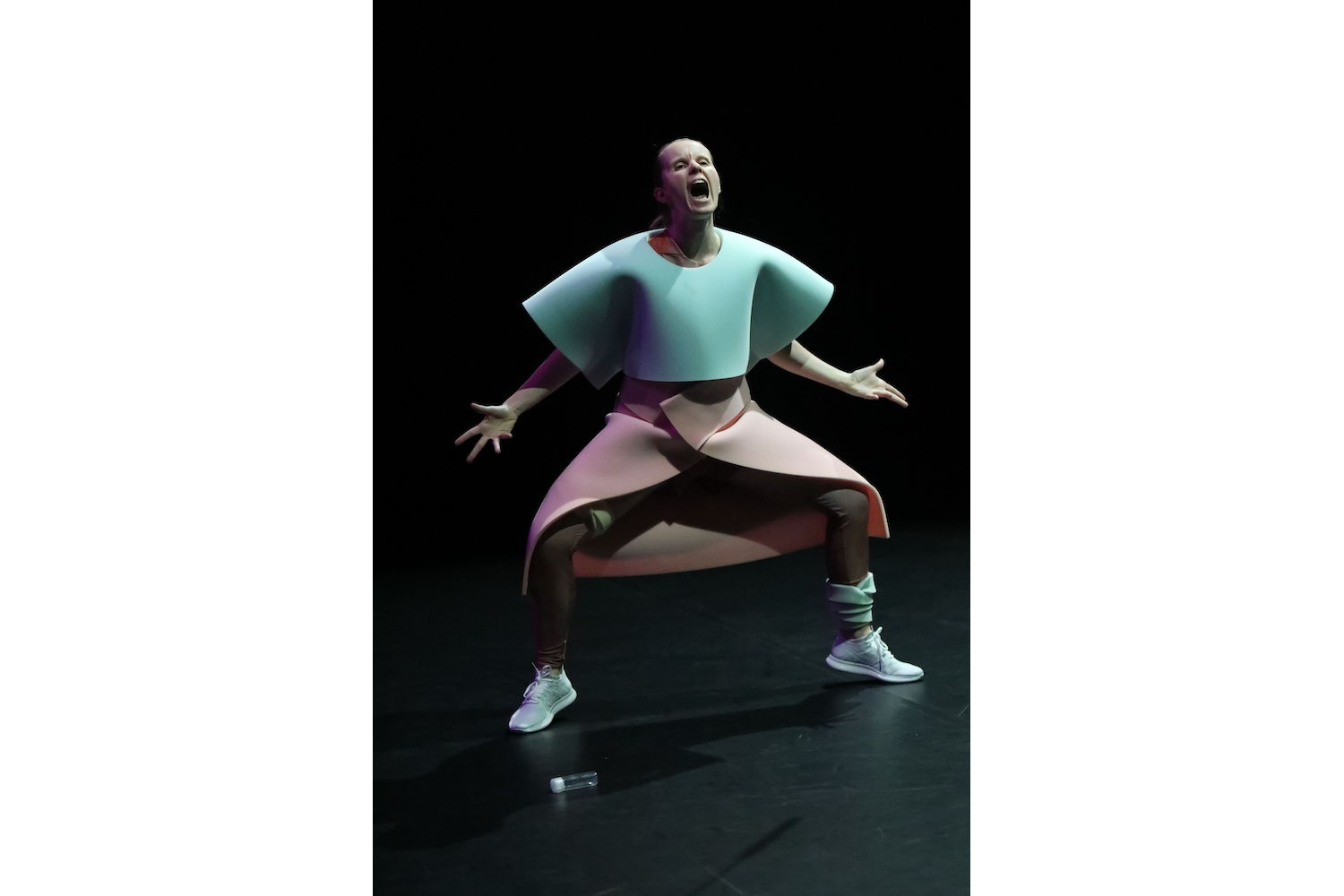

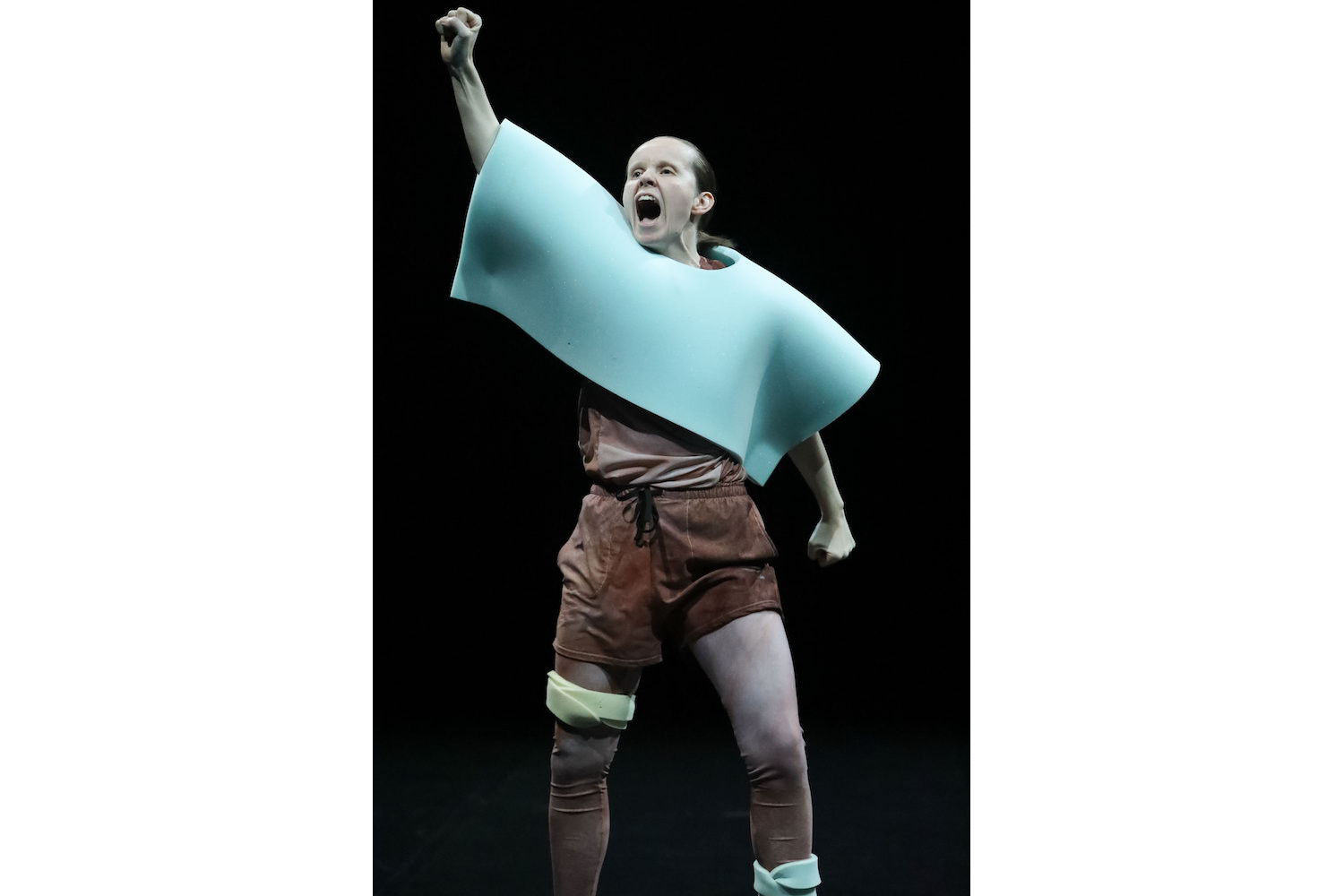

After ending Spring Forward online on a high, feeling grateful for the ability of the arts industry to adapt and stay connected at difficult times, I couldn’t help but slip into a bout of melancholy. Seeing familiar, friendly faces on screen, and being introduced to new ones, made me nostalgic for the live elements of viewing dance in a theater setting; namely post-show discussions, red wine in hand, and even being made fun of by friends every time I was caught dozing off in the middle of a performance. Watching Italian choreographer Silvia Gribaudi’s Graces on screen made me feel particularly sentimental, as it took me back to when I first saw the ingeniously funny work as part of B.Motion festival in Bassano del Grappa, Italy, with a group of other Springback writers in August 2019.

Memories of physical experiences are still quite fresh in my mind, but as coronavirus-induced restrictions continue, “Will we lose the memory of what it meant to go to the theater?” asks Ribot Thunnissen rhetorically. As many similar dance and theater festivals are set to migrate into the virtual realm — Berlin’s iconic Tanz im August festival recently announced its move to the digital sphere — it seems like it will be quite a while before we will be able to set foot in a bustling auditorium to experience live art. For example, Spring Forward 2020 was hoped to still be able to go ahead in Croatia this autumn, yet this plan has now been abandoned, and the next festival — which will be a “bumper four-day edition Silver Jubilee, twenty-five works for twenty-five years with guests from Korea, Japan, and Taiwan,” according to Ashford — isn’t set to take place until spring 2021 in Elefsina, Greece.

There is a worry among some members of the dance community that the introduction of online dance festivals will lead to the demise of live performance, and they fear that the cost-effectiveness and easy marketability will cause industry leaders to see them as future alternatives rather than temporary solutions. I am doubtful this will happen, as the resounding message from everyone I spoke to for this article has been that dance on screen will never live up to the “real deal.” Running online counterparts in parallel to live festivals, however, has been debated.

Even when we are allowed back into theaters, they are going to look very different: consider this eerie image of the Berliner Ensemble being stripped of many of its seats to allow for social distancing. “Our experience of the theater today also differs from what a theatrical or danced experience entailed a century ago,” says Ribot Thunnissen, noting the world’s natural disposition to develop and change. So, to refer back to Mark Twain, it seems that, whether we like it or not, the kaleidoscope of history is going to keep on turning, piecing together fragments from the past, and creating new and curious ways for us to experience art. Let’s just hope that the live element of performance is a fragment we’re able to hold on to.