As an individual accustomed to lengthy physical encounters when appraising exhibitions, my first attempt to write a review relying on digital resources — in this case: a virtual tour, a series of installation photographs, and an artwork checklist — felt restricted and rudimentary. While some online presentations might lend themselves to the task better than others, approaching Isa Genzken’s “Window” — now physically shuttered at London’s Hauser and Wirth — proved more complicated. The first complication can be attributed to the artist’s renowned fascination with modernity and visual culture. The work is emphatically three-dimensional and large-scale, a combination of sculpture, found objects, and assemblage, while the show’s themes — urban architecture, travel, reinvention and change — now hold a tragicomic resonance in our immediate circumstances.

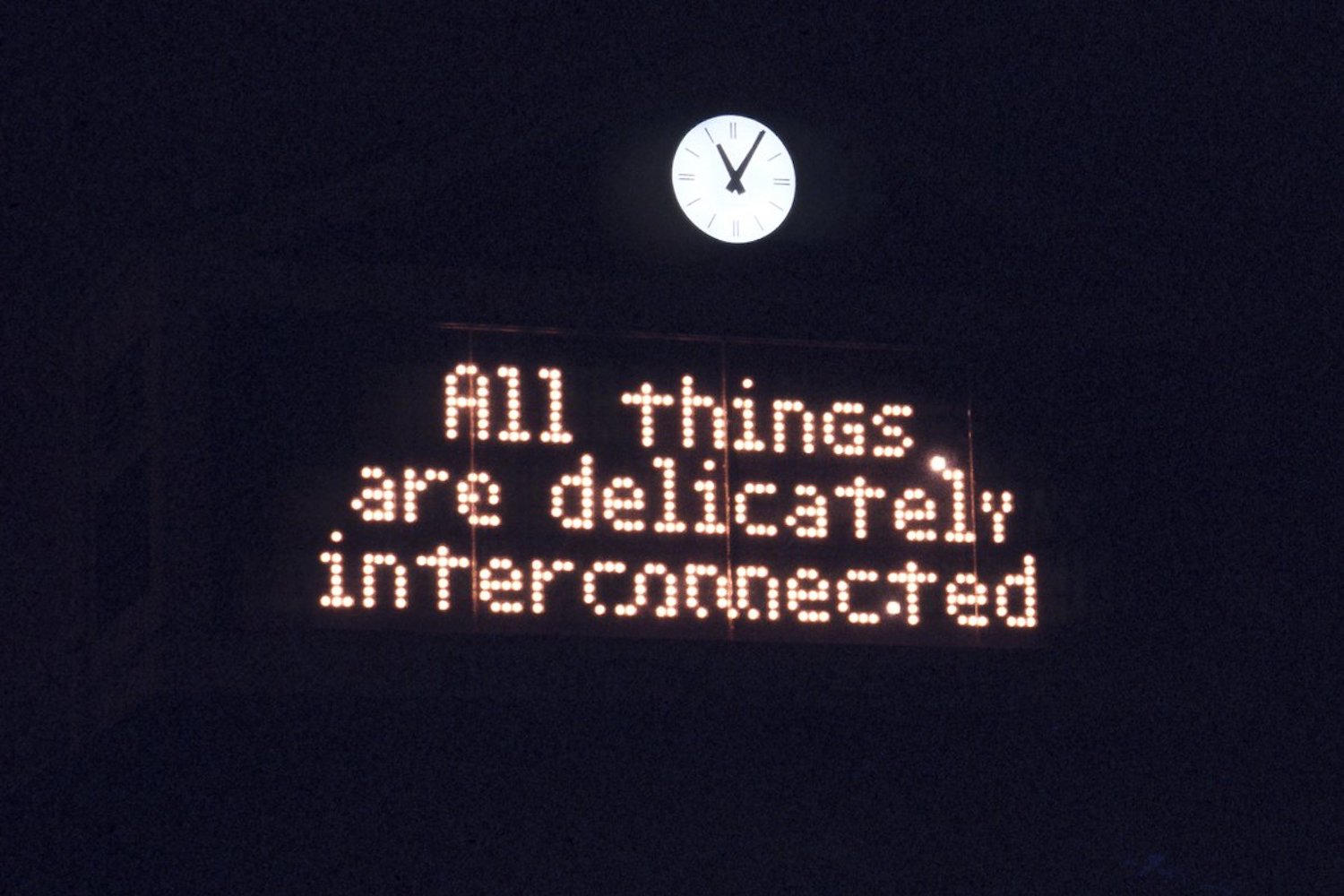

Throughout the gallery, a series of white sculptures, cast in plastic and concrete, and visually akin to architectural maquettes, have been positioned on plinths. These refer to a series of realized and unrealized projects undertaken by Genzken, in which the form of a window has been isolated from its original architectural purpose and installed within or alongside existing buildings in various European cities. In Spiegel (1992), for example, the window faces and reflects the Stadthalle in Bielefeld, Germany, akin to an enormous freestanding mirror. The latent absurdity of these windows is similarly channeled by the show’s central work, Untitled (2018), a deconstructed installation of an aeroplane. It is comprised of fifteen aeroplane panel windows, their blinds open, shut, or at half-mast (irrelevant anyway, as the only view behind them is a blank, white plaster wall), that surround three bench rows of seats, with navy patterned fabrics upholstering aluminum frames. There is something melancholic and relic-like about Genzken’s abandoned, obsolete cabin. With its aesthetic of grubby neglect and disarray, it is difficult to now resist the urge to imprint the impact of Covid-19 on the work, notably the collapse of the travel industrial complex. Previously, perhaps, the wider contextual backdrop of an art world that was beginning to reckon with its rampant contribution to the globe’s carbon footprint would have initially come to the fore. The accompanying exhibition text cites the aeroplane as representing the “instability of a global, homogenous society in constant flux and perpetual motion,” but what does this mean now that the world’s flux, our motion, is in stasis? Perhaps these parallels to the current situation are gauche or cliché, but Genzken’s work is deeply attuned to the spatial and psychic relationship between individuals and their surroundings, with the viewer often forced to re-evaluate their position. The work’s liminality, its sense of in-betweenness, feels inevitably pertinent.