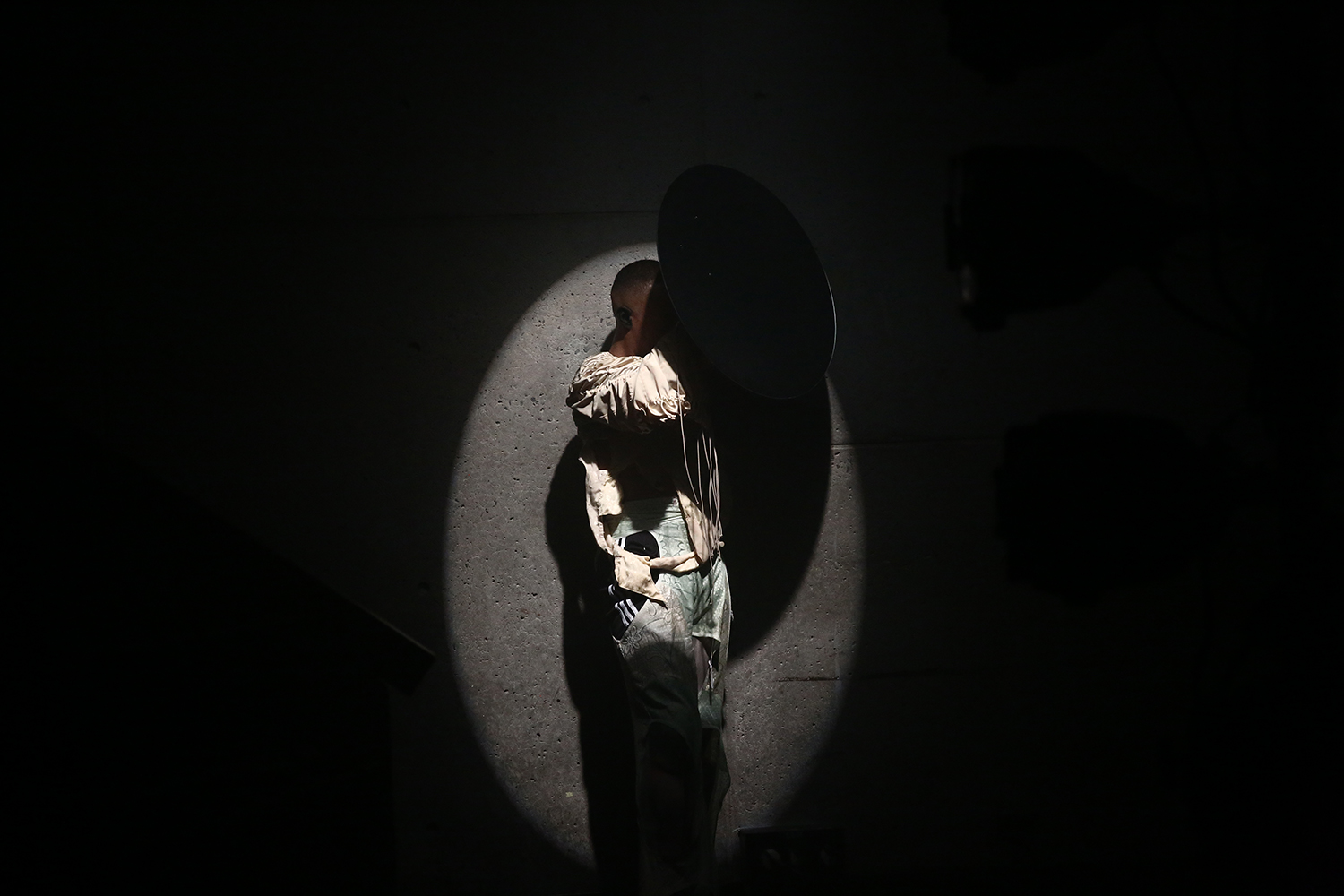

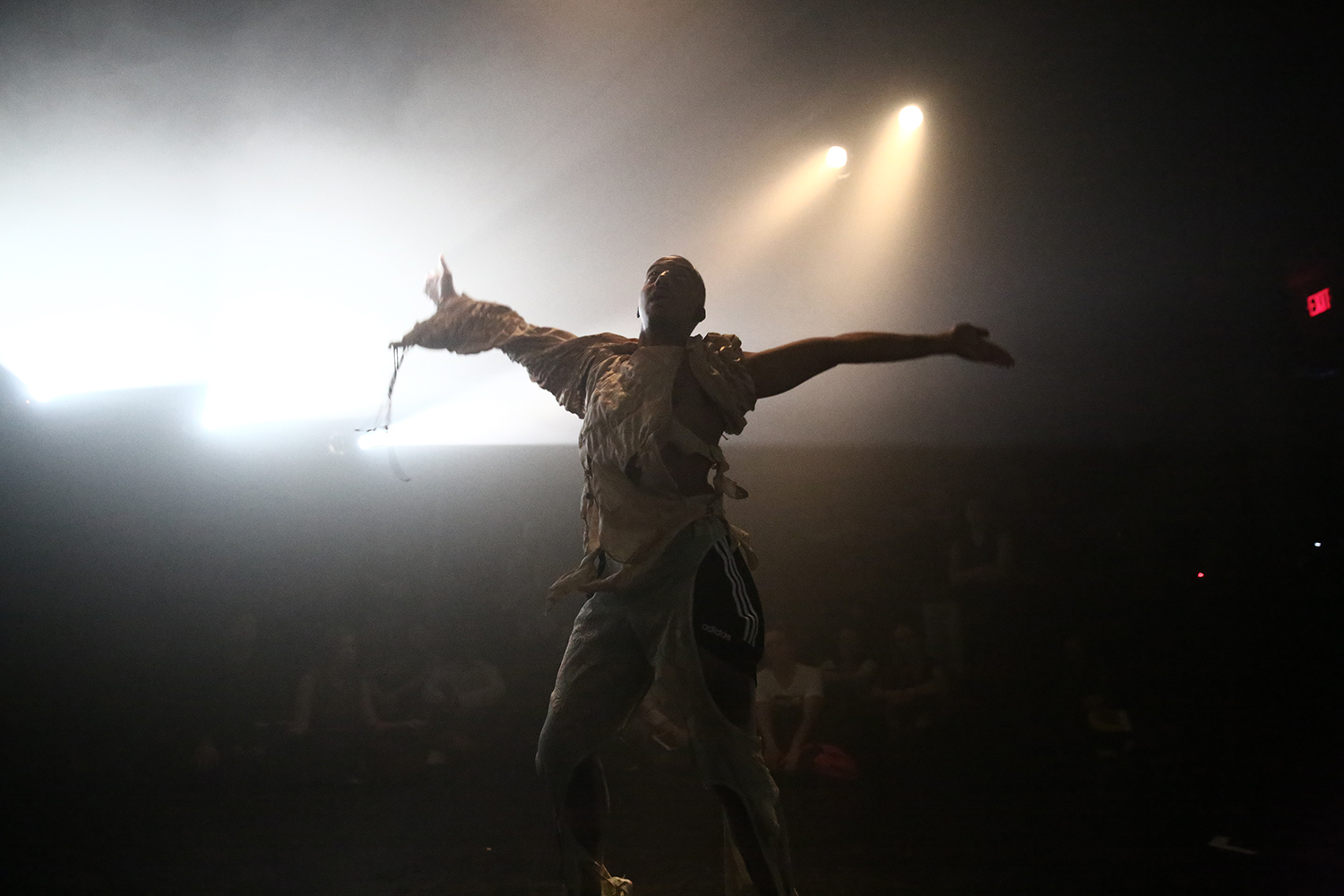

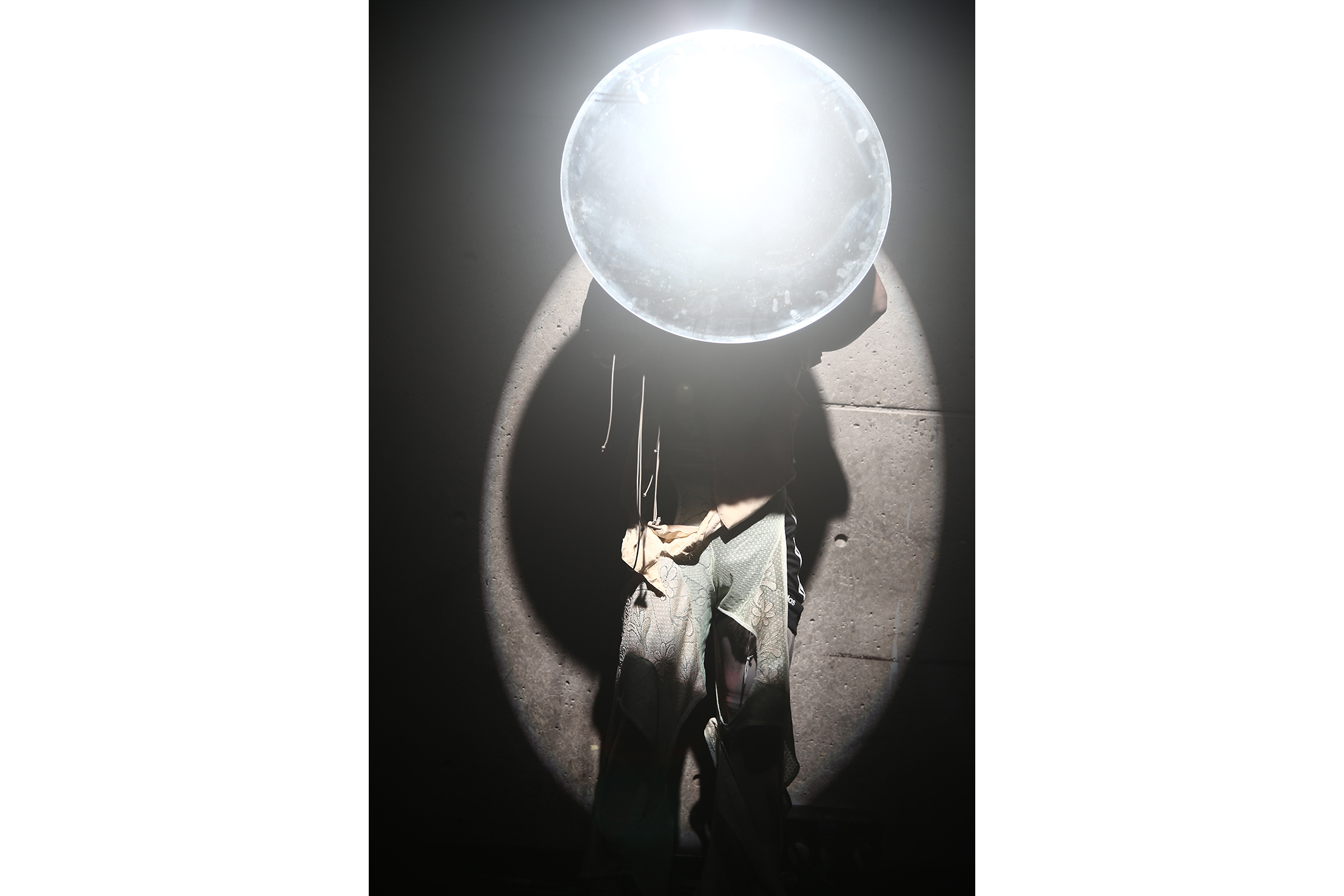

A collaborative live performance by Paul Maheke, Nkisi, and Ariel Efraim Ashbel, co-commissioned by Performa, Abrons Art Center, and Red Bull Arts for Performa 19, Sènsa plunges one into a sonic milieu of pulsing bass polyrhythm. In darkness, save for Ashbel’s agile, intermittent beams of light that, lighthouse-like, spot Maheke’s contortive motions always at the threshold of disappearance, Nkisi’s live mix surges without stop. The artists’ entry point evolved, in large part, from Bantu-Kongo cosmology, where life-worlds are understood as being generated by waves emanated and received. Sènsa, similarly, gives contagious reason to its audiences to sense, sweat, and tune themselves in co-composition.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Emma McCormick Goodhart: You instrumentalize space in Sènsa, making it vibrate and ultimately pass back through our bodies. You also referenced Stone Tape theory in your listening session for Performa, which gets at the agency contained in materials.

Nkisi: Yes, that was a really important moment for Paul and me, when Stone Tape theory came in. We were thinking about a performance where the space itself can take its own agency — not by our giving the space or the architecture its agency, but where the architecture takes its own agency. How can we give the space its moment? We did a first tryout of that part of the piece at Cafe OTO, where I had a residency. That’s where we tried using piezo mics for the first time, and it worked really well. The fact that there’s no stage meant that Paul had to move around people. That was an important moment in the whole trajectory of the project, to understand that it was important to have this proximity to the audience — for the audience to be immersed in sound, light, music, and movement. That there was no separation. In Sènsa, I feel that in the gaps and moments where there is no information it becomes so full; it’s actually the moments when we take stuff away, or hold off, when the most interesting things happen.

EMG: How did you acoustically “dress up” the concrete performance space at Abrons, given that concrete can be an acoustically unwieldy material?

N: In Abrons, it became interesting for me to think about the kind of excess resonance that I could play with: in looping, in the effects on top of the drum patterns, and even on top of the recordings of the piezo mics, where I could use that extra “dirty” sound to really make the space vibrate, so that all the bass wouldn’t just get sucked in by the walls. Piezo mics were installed on the floor, so certain movements that Paul made would register as sound, and then be processed through various effects. A lot of my references come from the field of cosmic time, and from archaeoacoustics and spectralism. In the overture, there was a sound piece made with real recordings of pulsar stars. I like this idea that, weirdly, the sound of Paul moving near the piezo mics reenacts a similar texture of sound. As a musician, it’s hard to think about putting all those ideas in a five- or ten-minute track, so it becomes interesting to have an opportunity to actually put all this research in a piece in the context of performance, where it becomes possible to think in other ways about rhythmic and beat-based music. I’ve always been interested in what would happen if, instead of forcing sound and music in the realm of entertainment, you think about sound as a tool to communicate, or a tool to heal.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

Paul Maheke and NKISI, “Sènsa.” Live performance at Performa 17, New York, 2019. Co-commissioned and co-presented by Performa, Abrons Arts Center and Red Bull Arts. Additional support provided by the Performa Commissioning Fund, Arts Council England, FUSED (FrenchU.S.ExchangeinDance), and the Flemish Minister for Culture. This project has been selected and supported by the patronage committee for the arts of Fondationdes Artistes. With additional help from ICA London. A first iteration was developed in collaboration with Block Universe, London. Photograhy by Paula Court. Courtesy Performa, New York.

EMG: The circular mirror that Paul moves with serves as a visual portal or a threshold. What sonic portal or threshold do you build in Sènsa?

N: I’m very interested in this idea of resonance and how certain frequencies can make us resonate with them, as with rhythm — the connection between rhythm and heartbeats. I’m always interested in how to get to that through looping, to be able to get the whole collective body in sync with sound, and in whatever can happen once that portal gets opened. I feel music forces you to think about how audiences possess their own agency, as vectors in whatever energy gets pushed around or created. It’s also been important for me to come to the idea that energy never goes away; that when you create energy, it will stay there forever. When I was younger, my mum would always tell me to be careful with what I said, because you actually materialize it. It’s the idea that your voice creates materiality, because your voice waves become voiceless waves, become concepts, become dreams. The Bantu-Kongo believed that a lot of information would travel through dreams as the visual effects of the voice.

EMG: Can you elaborate what you mean by “sonic vision,” a thematic central to Sènsa?

N: For the Dogon, and even in Bantu-Kongo cosmology, the act of perceiving sound is the thing that creates reality around us — which means that a visual, or an ocular, sense of vision is actually like a reaction, much more subjective than we might think. I’m interested in thinking that sound might be the place where we can actually retune our vision or our visuality.