The title of the second Okayama Art Summit is a half-formulated hypothesis: “If the Snake.” I guess we’ll never know. A partial and open-ended application of the scientific method, however, does make an apt caption for the fascination with science among contemporary artists and the uses to which they put it: more often than not, the appropriation of technologies and methodologies, from bioengineering to computer learning, in the service of evoking a mood. Unsurprisingly, this fascination is marked by ambivalence — between the ecstasy of innovation and the terror of ecological devastation — and that stillborn conditional clause, if the snake, could just as well be taken as the start of a speculative fiction; you can guess how it ends. At sites around Okayama we encounter algorithms, simulations, AIs, and ecosystems as well as dystopian tableaux: science fair and haunted house.

Over the past decade and a half, Pierre Huyghe, who helmed this, the second edition of the Okayama Art Summit, has been working this territory, drawing on botany, zoology, biotech, and neuroscience in videos, sculptures, environments, and image flows, served with an eerie, sci-fi-ish approach to installation and exhibition design. It could be said that he set the table for the current apocalyptic pageantry and techno-futurist fever dream that a few years ago they were calling posthumanism. Beyond his own contributions and collaborations, Huyghe’s presence is felt throughout the exhibition, in a curatorial voice of God and the long shadow of influence.

The show’s main site is the abandoned Uchisange Elementary School, and there, in a dirt field, a large projection screen displays frantically mutating imagery of a murky and generally biomorphic sort. A project that Huyghe debuted at the Serpentine Galleries last year, the largely illegible flickering torrent was created by a neural network translating thought patterns measured by fMRI scans (untitled, 2019), a process developed by Kyoto University neuroscientist Yukiyasu Kamitani. Before sliding into the scanner, Huyghe’s subjects were presented “a set of private ideas and memories” in the form of “images or descriptions” and asked to imagine them, though the end product is pretty much indistinguishable from the results of the research Kamitani shows off on YouTube. It’s hard to imagine what use or meaning could be made of the experiments, apart from demonstrating how fast minds work — human and computer — and to show that this can be done. Perhaps it is that uselessness, in the Wildean sense, that drew Huyghe to Kamitani’s lab, though I’m sure the novel aesthetic of the optical stammer didn’t hurt. If there is a menacing quality to this cognitive effusion, it may be because it gives anxious form to something we assume is happening all the time — the harvesting and quantifying of our private ideas and memories — though I guess the silver lining, which a lot of us assume anyway, is that there isn’t really much to see.

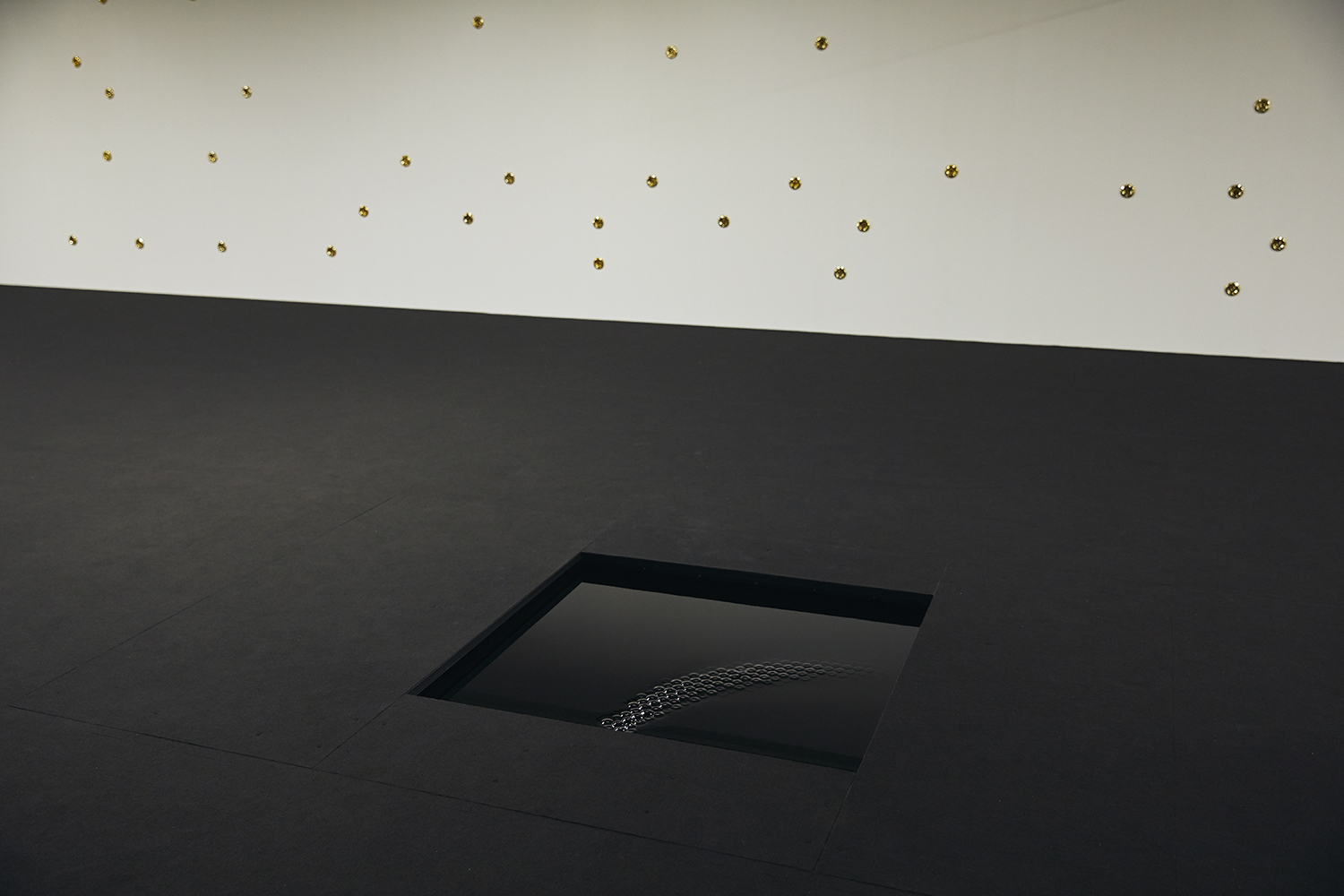

Inside the school, Huyghe teams up with Matthew Barney, each artist presenting a container filled with fluid (untitled, 2019). Barney’s, an electroplating tank, contains an engraved copper sheet coated in asphalt and soaking in a neon blue bath of acid and copper. As electrical currents charge the solution, more and more copper will build up along the lines of the engraving. When the exhibition wraps up, the plate will be removed and placed inside Huyghe’s neighboring aquarium, presently sparsely populated with a couple anemones, some coral, and, allegedly, an arrow crab and horseshoe crabs. Huyghe has been exhibiting aquaria since 2010, moodily lit aquatic theaters billed as Zoodrams, exquisite little ecosystems that reflect in miniature our own social systems — the drama of the exhibition, the fishbowl of the art world, with hermit crabs taking up residence inside replicas of the head of Brancusi’s Sleeping Nude. We’ll see how it goes with Barney’s engraving.

If it took a couple of readings of the wall text to get what was happening in Barney’s tank, no such didactics were on offer to explicate the work that consumed the vast majority of the school’s interior, Fabian Giraud and Raphaël Siboni’s The Form of Not (Infantia), The Unmanned, Season 3 (2019): an installation of snaking tubes, heaps of goop, pierced walls, tarps and fabric — plastics, plaster, metal, and dust. It sprawls through room after room over the building’s two floors — here molds in a chalky looking substance, there a bunch of craggy ceramics — with spooky lighting provided by dislodged fluorescents. At the center of this labyrinthine outburst of materials is their film The Everted Capital (1971–4936), The Unmanned, Season 2, Episode 2 (2019) — surprise! — a dystopian sci-fi with a droning score, set in this very abandoned school over the course of three thousand years. I was reminded of Huyghe’s own sci-fi film set in an abandoned building, The Host and the Cloud, and though I can’t claim to have sat through all of Everted Capital, I managed to catch this line: “Though their demands remain unclear, it is obvious now that they are determined to remain and let themselves — and their hostages — be terminated with the Earth.” I can take a hint.

Back outside, Pamela Rosenkranz has filled a swimming pool with pink liquid, a gurgling cosmetic soup that, they say, is “based on a standardized European skin tone” and “reflects on the human subject as a fluid trace, one whose physical and psychic constitution has been manifestly transgressed and altered through the omnipresence of synthetic materials” (Skin Pool (Oromom), 2019). If there is something hopeful in the act of liquefying the Herrenrasse into a Pepto-Bismol pond, this hope apparently depends on the dissolving of the human subject itself. In this Rosenkranz has a lot of sympathizers among the artists brought to Okayama, the most proximate example — and the most literal — being Etienne Chambaud’s Calculus (2019), a bronze replica of Rodin’s The Thinker with the thinker himself removed, leaving only a lacerated base.

Rosenkranz’s liquid bubblegum monochrome is, I’m told, supposed to reflect the floating frog on the massive screen affixed to the front of the building across the street. I didn’t really see that, but it does provide a stunning and slightly nauseating contrast in a somewhat colorless city.

The frog belongs to John Gerrard and marks, along with Rosenkranz’s pool, one of the highlights of the show. X. Laevis (Spacelab) (2017) presents a reimagining of an experiment undertaken on the Space Shuttle Endeavor in 1992 in which scientists set out to answer the question of whether frogs could reproduce in zero gravity (the answer is yes). A slow-motion digital simulation, rendered in real time by a video-game engine, the frog hovers in zero gravity, its legs occasionally spasming, as the gloved hands of an astronaut forever reach out to grab it. It’s mesmerizing. It also offers a fitting image of the exhibition, and for the current allure of science for art: like Huyghe’s stream of nearly perceptible mental images — just there, but never grasped.