Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

If there is a common element in recent experimental dance, theater, and performance art, it is the noticeable absence of borders. Certainly postmodernism had already made deliberate use of hybridity to challenge modernist notions of fixed cultural perimeters, but in more recent years that fluidity between art forms has become a full-fledged reflection of our times. It seems that the zeitgeist of today is, to use Judith Butler’s words, the performativity of gender; the subject is no longer considered as a static entity but, on the contrary, as part of a continuous evolutionary process. To put it differently, the monolithic notion of gender is unable to fully grasp the multiplicity and complexity of identity.

This concept turns out to be particularly fitting for the Farm in the Cave (Farma v jeskyni), an international theater company from the Czech Republic whose identity hinges on physical theater, dance, and performance art. Over the course of nearly twenty years of activity, heterogeneity and hybridity have become their hallmarks — or rather, a means by which to undermine the persisting cultural hegemony. Their multifaceted nature arises out of a particular approach based on long-term research, frequently focused on sensitive sociopolitical themes. Many of their theater events, performances, choreographies of objects, video installations, and site-specific projects are the result of collaborations with non-professional performers, theater scholars (among them Jana Pilátová and Sodja Lotker), and creators from different backgrounds and minority cultures.

For the Czech company, working beyond the conventional parameters of genre is also a creative strategy to discover new forms of expression — forms that wouldn’t normally fit into mainstream theater programs or fixed aesthetic categories. Unsurprisingly, some of their productions have been realized for and presented in unconventional spaces, such as the former casino at Pařížská in Prague (Intervention, 2012), the Žilina-Záriečie Railway Station (Journey to the Station, 2003), and NoD experimental space (Prague).

On the occasion of the latest edition of the Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space, they further challenged themselves with a new experiment, Night in the City. This is a one-off seven-hour performance partly conceived as an explorative journey through the maze-like architecture of the DOX Centre for Contemporary Art — the multipurpose, cross-disciplinary art center that co-produced the project. The event could be considered as a further development of Whistleblowers (2014), Together Forever! (2016–17), and Refuge(2018), their three previous productions based on a series of encounters with specific groups and communities. But unlike these initial incarnations, this long-duration event is conceived as a single total work wherein a spectator’s expectations are continuously reshaped by an ever-changing performance-audience-space connection. One of the recurring features of the Czech company’s productions is, indeed, to integrate spectators into the “apparatus” of the event. The aim is to challenge their knowledge of genre conventions and perceptions, without however turning them into some sort of narcissistic “prosumers” — a role increasingly popular in participatory theater.

In Night in the City the spectator is well aware that they are the subject of subtle manipulation and must therefore accept a certain degree of passivity. After all, what is at stake is the way they experience the performance, not the obliteration of their usual function as spectator. During the event, participants are invited to sit or to move through the DOX space, following three non-expressive and identically dressed performers in the guise of modern muses: their main task is to drive along the entire performance through the labyrinthine architecture, helping to choreograph the mobility of the spectator.

By turning up unexpectedly in the hall and playing a horn, they usher in the beginning of the event. As the large doors open, some people stand in tableau behind the windows along the corridor. Only at the end of the night will their significance, in terms of their role in linking the performances and giving clues about the characters, become clear.

Other doors open, and the first performance the spectator is invited to attend is Whistleblowers, a disturbing enquiry into the scandal of a world food company. It is a complex choreographic piece that integrates live music by Marcel Bárta and a dynamic, staccato performance by seven dancers who seamlessly interact with a variety of objects: a table, a coffee machine, a rug, a bowl of milk. It is not clear whether the objects provide indirect references to corporate identity, but what is certain is that these objects are neither dance props nor surrogate performers. On the contrary, these ordinary elements function as “moving-things,” just like the seven performers and their geometry of movement. In the choreographic logic of this performance, both animate and inanimate elements (objects, gestures, and dancers) become impersonal and non-instrumental entities inscribed into a sort of non-hierarchical and horizontal field. They symmetrically co-determine each other. Within this sinuous flow, the performers interact with real-time video and previously recorded projected images, suggesting an overlapping space-time. This is in keeping with a disregard for narrative approach, betraying a disinterest in re-creating events via linear storytelling.

In other words, in the same way that a collage mixes media and images, Night in the City resorts to associative thinking — according to neuroscientists the foundation of all thought — rather than verbal reasoning. Through their choreography of “moving-things,” live music, and the dehumanized automatism of performers, the Czech company allows spectators to unlock their own memories in order to connect with the performance. They do this through auditory, visual, and kinesthetic means.

In such an ongoing process of meaning making, mobility plays an important role. By walking from station to station, the spectators are engaged in a continuous reconfiguration of spatial relations, assembling the dramaturgical fragments of the performance along the way. Before attending Together Forever!, for example, the three muses lead audience members in front of a screen showing some portraits of people with corresponding quotes. They are the six senior, non-professional actors involved in this piece of physical theater — part of an experiment with an ideal coexistence beyond any form of discrimination, including ageism. This time the setting is an elevator. Inside, a pinwheel of effects and absurd actions combine dance and mime in a shocking, polysemic performance. In the background is a hostile mother-daughter relationship, suggesting the moral fragility of the human condition. The result is a kaleidoscopic juxtaposition of images, an alternating sequence of insanity and playfulness, whose effect is a mesmerizing emotional vertigo.

The aspect of pilgrimage within Night and the City proves also to have a political significance. In Refuge, the last part of the event, spectators are engaged with issues regarding human rights and the related question of transnational migration and diaspora. With a nod to the documentary mode, the Czech company has realized this performance by interviewing a community of political refugees in London, with the aim of investigating Tibetan exile. While moving toward the final performance, spectators wear headphones and listen to voices talking about their escape. While the use of prerecorded audio risks becoming slightly patronizing, bombarding spectators with information, on the other hand this sensory experience enhances a sense of immersion, essentially to the juxtaposition of what is seen and what is heard. The company manages to avoid falling into the trap of “verbosity” by giving rhythm and time to this transitional phase. After this short interlude, the spectators are ushered into the elevator, where a woman is singing a melancholic melody — a Montenegro folk song — after which they are left alone in silence by a campfire.

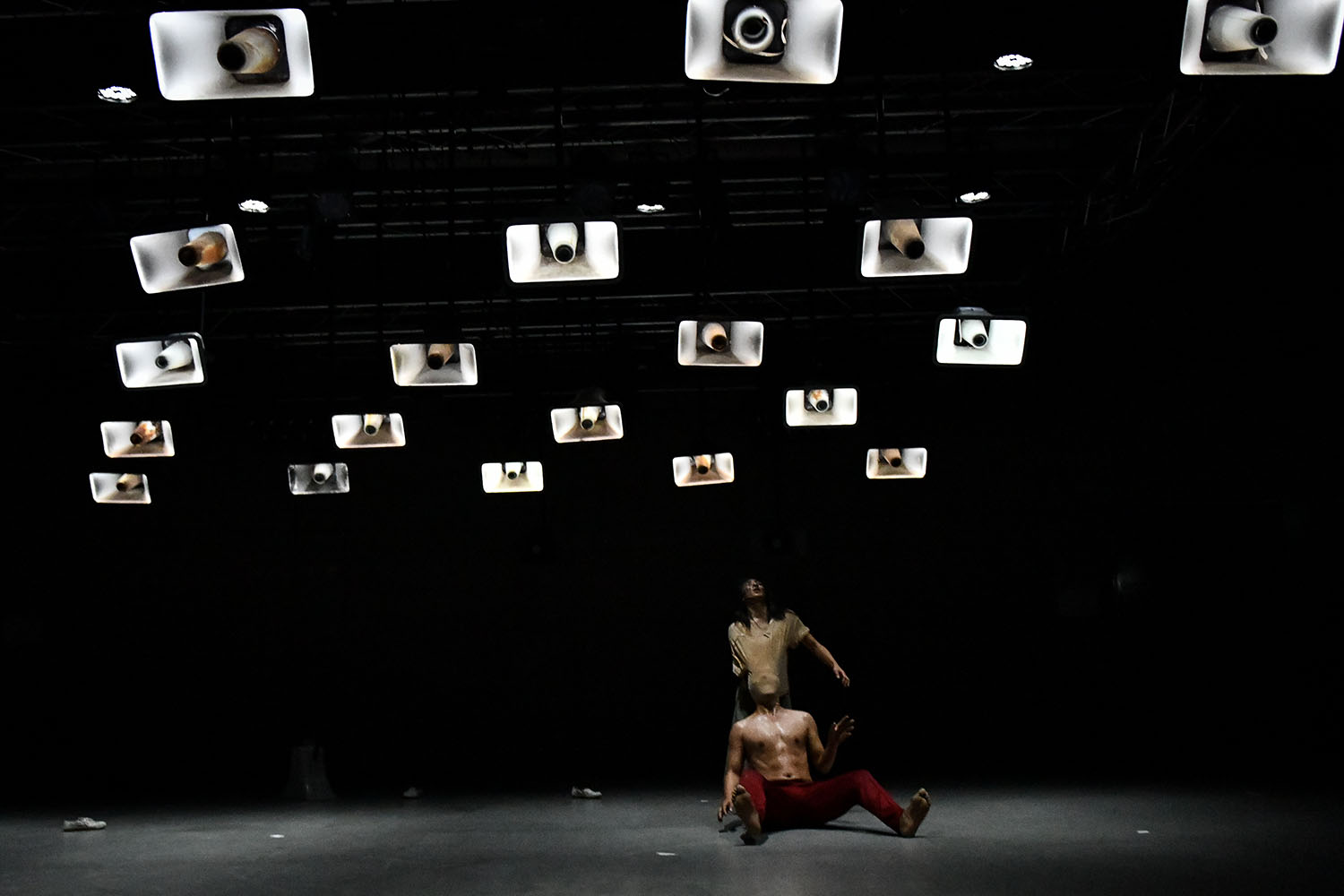

At first, Refuge offers itself to spectators’ eyes as a hushed and uncontaminated picture framed by a dozen illuminated speakers. Gradually, all its elements — music, dancers, light, and a darkly elegant grand piano — arrange themselves in the space, resonating together. Little by little, the live wind and percussion music envelopes the four performers. The gradually increasing tempo of the music then turns into a threatening sound, mirrored by frenetic movements and the menacing image of the rotating piano, now resembling a dark angel with its wings spread. Overall, the performance is a visceral representation of the human stories that the company has witnessed. Through the use of image and testimony, they powerfully evoke the sense of uncertainty that exile and emigration create.

Night in the City is a complex and stratified project that embodies, without banality, the notion of “nomadic thinking” — that is to say, thinking on the limits of freedom, to use an expression of Deleuze and Guattari. This long-duration project shows how far we can go, beyond static and ossified ideas, to mobilize a reimagining of fixed places and borders. It reminds us that the mind in motion shapes all thought.