In Julien Ceccaldi’s comic Solito, published to accompany his solo institutional debut at Kölnischer Kunstverein, an androgynous thirty-year-old, jobless and stagnating at home, ejaculates, in a penetrative fantasy, on their doll-cum-confidante, Marie-Claude. Rats gnaw the doll’s face while Solito drifts to sleep. Miraculously, this reveals a door to an Elysium of candy meadows and strawberry milk rivers. Here, the virgin Solito slides into a hazy love triangle with Marie-Claude and a hulky, sensitive cadaver named Oscar. Like all arrangements based on unobtainable projections, it ends achingly.

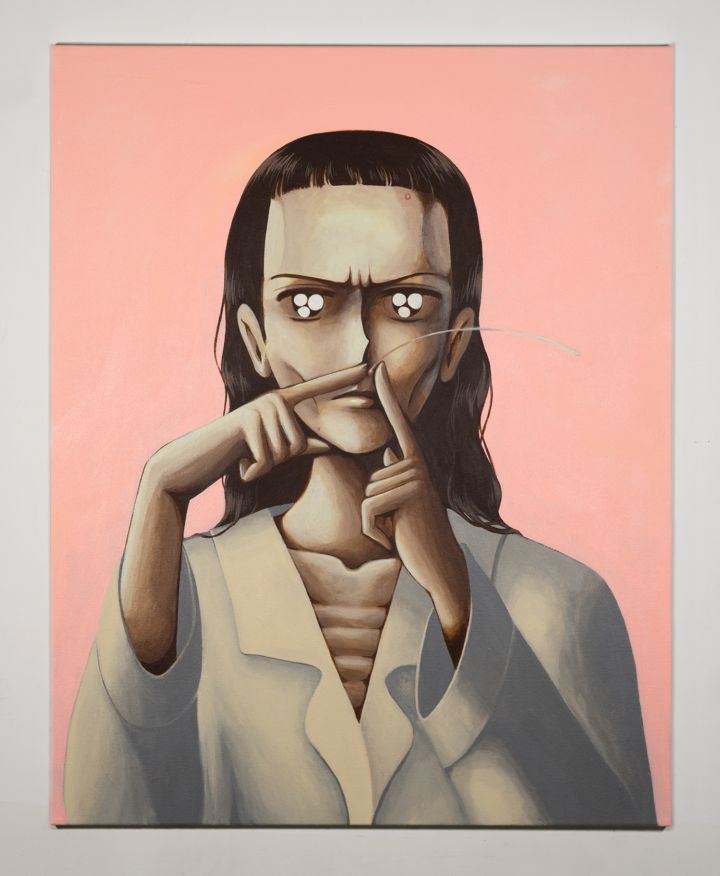

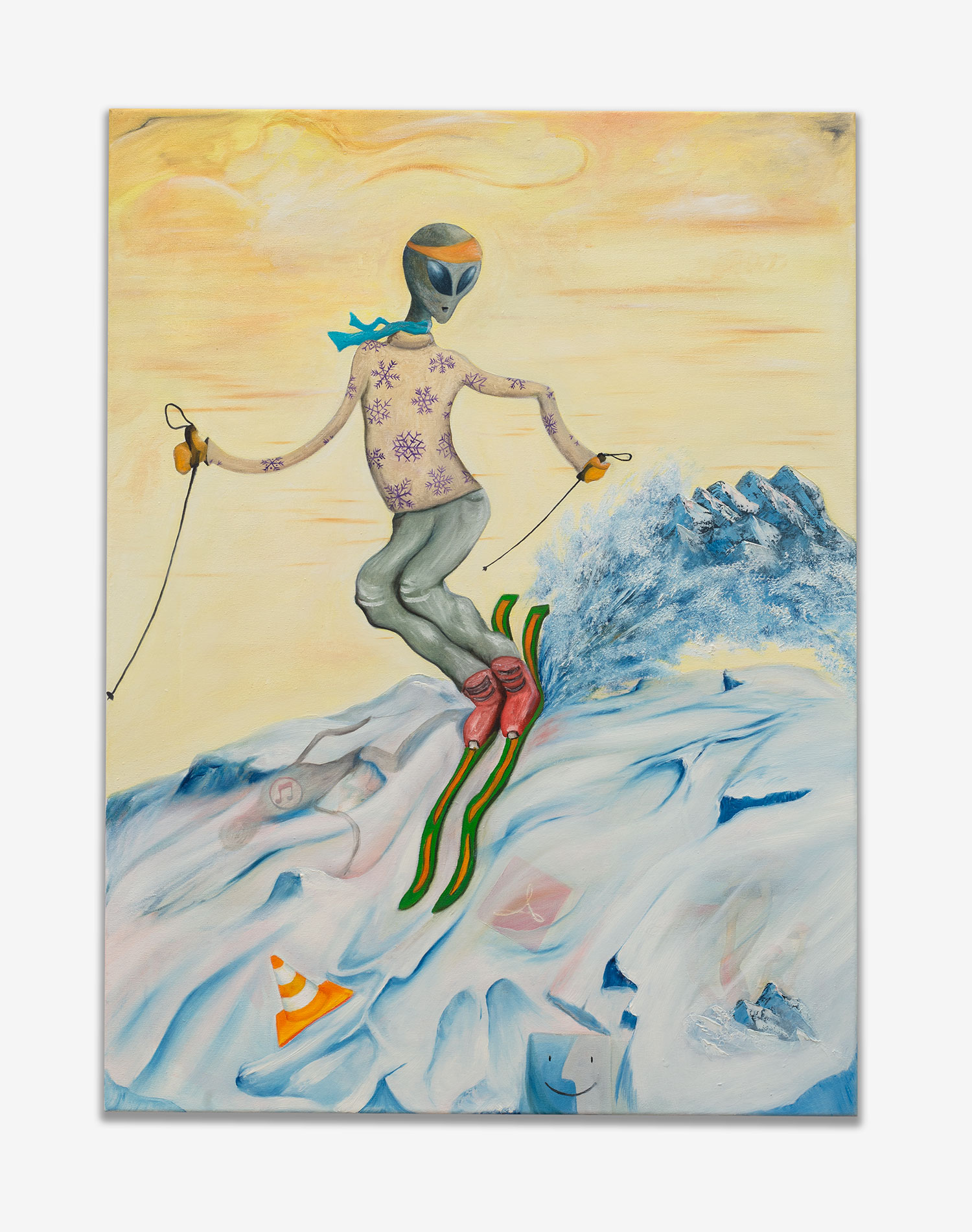

Ceccaldi’s an intrepid chronicler of the isolations of unrequited desire. While his comics, with their deft, sensitive lenses upon the injustices of gender and identity, teeter along pleasingly humorous arcs, his artistic installations, of which this exhibition comprises the most ambitious to date, eschew narrative. They share Roland Barthes’s understanding of the discomposing and histrionic nature of love’s discourse: his intuition that, in love’s agonizing phantasmagoria, “the end, like my own death, belongs to others.” Across three floors, the artist extracted and exaggerated scenes from the print publication, as if yearning his characters into the real world, or seeing them in every surface. Works on canvas, utilizing the cel technique of traditional hand-drawn animation, floated intricate illustrations over pastel backgrounds, though I wondered if they’d gain depth through more catalytic layering. Murals developed a logic of, ahem, misery-en-scène, gestural brushstrokes evoking a vulnerability that bled into the gallery through readymade props. Affect was enhanced when artworks overlapped. In one constellation, framed ink drawings hung over a mural depicting a sickly, pining Solito. In front, an expressively torqued sculpture of a wigged, wood-stained corpse gazed skyward, like an anatomical skeleton moonlighting within a Bernini altarpiece.

Solito acknowledges diverse influences, from drag to the mangas of Kunihiko Ikuhara and Riyoko Ikeda, blending these into an affirmatively strange vision of the languorous subject. Its psychological debt is to Hans Christian Andersen, referencing The Little Match Girl (alongside other fairy tales like E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Nutcracker), and Andersen’s vivid diaristic accounts of masturbation.. Stained cartoons on large PVC sheets filled the Kunstverein’s windows, blocking the Cologne cityscape while broadcasting Ceccaldi’s wicked compositions streetward. Capturing the psychic split between interiority and exteriority, these showed the disreality of queer life in a heteropatriarchal world.