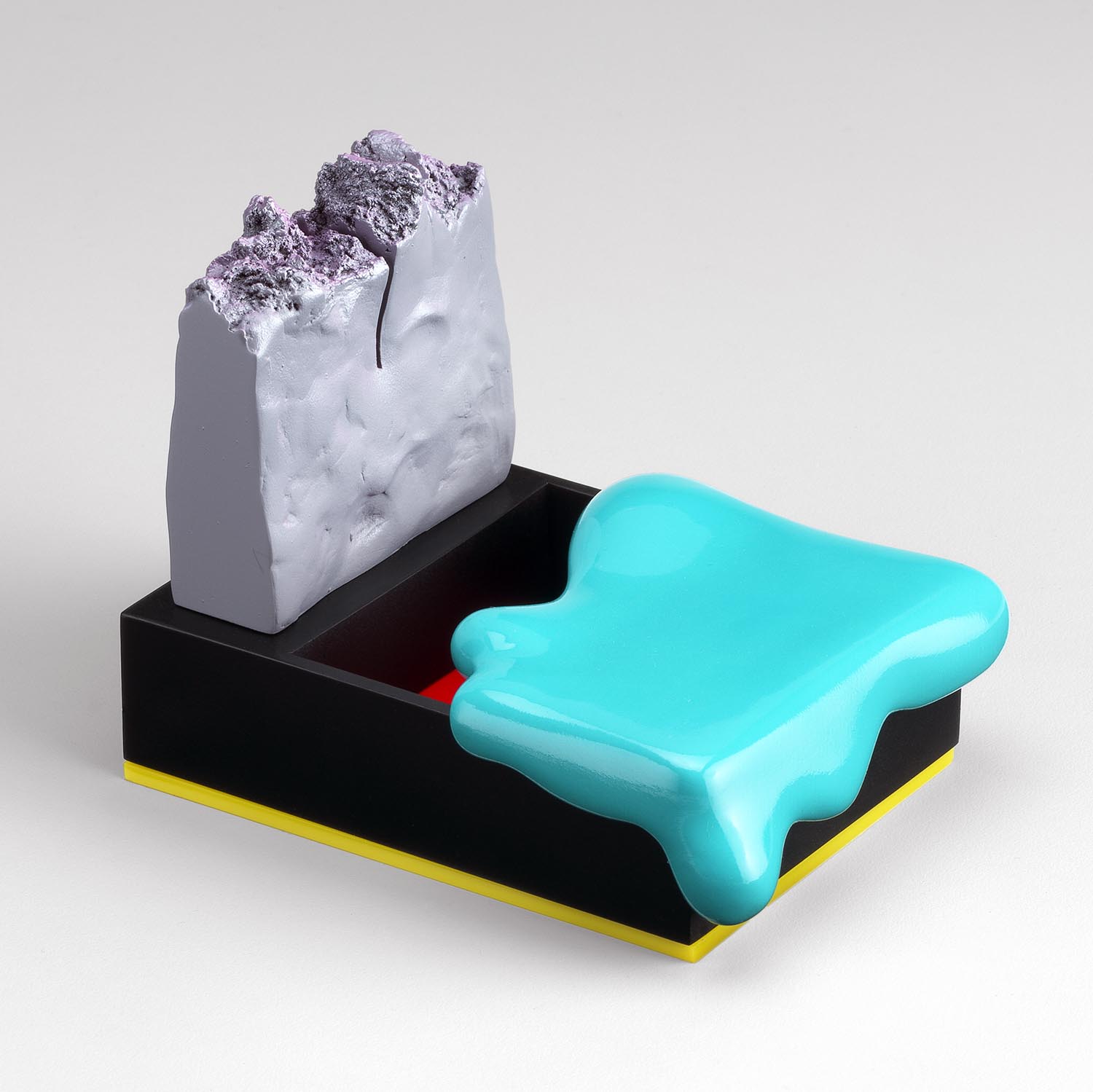

Seascape (2014) is a Turner riff at Water Lilies scale, painted by a robotic mop. One can mostly appreciate this grand work from close up, where indeed the turbulent hues separate into “mop strokes” of uniform size. Try to see the whole painting straight on, however, at a distance, and the exhibition’s titular “male gates” invade the view: Gate 1 through Gate 5, a series of five paintings on metal detectors. Their treatments range from a beige monochrome to high-energy sprays of high-gloss enamel — all accent colors, without compliments.

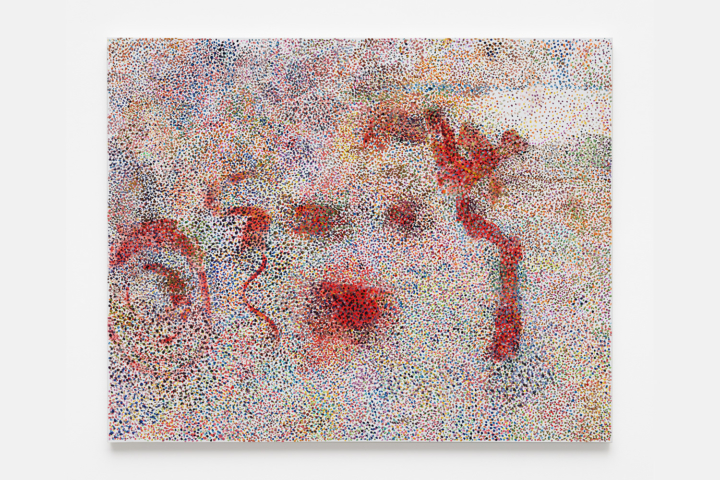

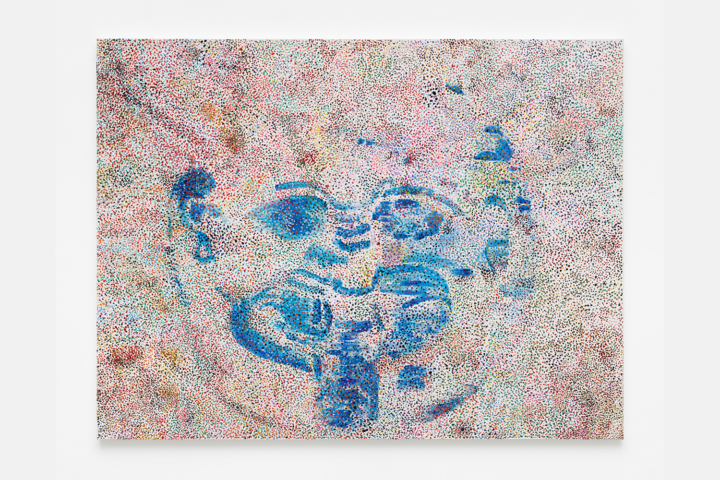

Walking through the detectors is an almost harrowing moment of viewership. They’re not on, no officers wave you through, no alarms go off, but the glossy panels press in close; you can see your reflection in their sheen, and you can smell the new paint. From across the room, a series of smaller paintings (Medusas, 2018) seem to nestle inside the metal detectors’ arches: clattering pointillist renderings of clichés like a Mickey Mouse water tower or a leering skull. The points are bold, but the paintings tend toward noise and gruel.

Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s Gates (2005) decked central park months after Reena Spaulings opened their New York gallery. Tourists and locals alike queued slowly, rain or shine, beneath the orange flagged structures, a more optimistic version of the gates through which visitors to JFK, LGA, and the 9/11 museum must pass. In Tai-Chi and other “energy work,” the body’s gates regulate the flow of qi — much like, on another scale, checkpoints regulate the flow of bodies, subtle and otherwise. Looking at these expressive paintings, framed by deadpan gates, the dominant “emotion” is exhaustion. It is the pristine exhaustion of the international artist (Reena or her incorporated parts) who finds herself at a loss, creatively blocked, on line at airport security. These slow gates are the sphincter at the end of the fluorescent, intestinal queue; the longer she fixates on this point, the more that deeper prison starts to seem like a fresh way out.