After successfully raising 3.5 million of a five-million-dollar capital campaign goal, the Swiss-born, New York–based nonprofit Swiss Institute (SI) announced plans in March to move out of their now-former Wooster Street space in SoHo into a permanent location in the East Village at 38 St. Marks Place. The conversion of a compact, four-floor complex — formerly a Chase Bank branch — was designed and overseen to completion by Selldorf Architects, an architectural firm with a history of art institutional and ivy-league university clientele.

SI inaugurated its eastward leap with a celebratory, filled-to-the-brim group show titled “READYMADES BELONG TO EVERYONE,” curated by Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen, co-directors of exhibitions at the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta) at ETH Zurich. Featuring roughly fifty artists, architects, and collectives from sixteen different countries, the exhibition aims to track a history of exchange between artists and architects who employ found objects associated with urban space. It is scheduled to run through August 19.

The “readymade” as a term and perhaps a strategy as set forth by Marcel Duchamp via his urinal-cum-Fountain (1917) — the performance of an authored gesture placed on display — has had a lasting imprint on art’s discourse, causing a myriad of fractalized courses of influence stemming from this necessarily singular gesture. Each tangential journey leads one down a path closer to success in the form of an exhaustion of all options — a goal that may have led to the curatorial logic so playfully demonstrated here.

Crowning the accessible roof area, artist Valentin Carron’s built Vecchio Cuore (2018), or “Old Heart,” is a purple heart-shaped platform made from painted wooden planks that stands as a casual stage or platform. Crowds naturally congregated here during this first weekend of private preview events, proving it a natural gravitational center for social bodies.

This piece by Carron, along with a selection of other commissions, is conceived as an architecturally site-dependent work, but still manages to find dialogue with the works on view as part of Fischli and Olsen’s curated group show. The commissioned works are the first of more to come as part of the newly launched SI ONSITE program. This ongoing initiative will continue to present special projects as a series of semi-permanent, continually unfolding installations that meaningfully activate aspects of the building’s non-gallery sections and sub-spaces — the reception area, reading room, stairways, hallways, roof, and elevators.

Hans Haacke’s Swiss Institute Visitors Poll (2018), also an SI ONSITE commission, surveys attendees and lets the resulting demographic information speak for itself. Visitors navigate the prompts of an iPad as they would a standardized test, and upon completion of the questionnaire are encouraged to suggest a question they would have liked to see included. The participants who have successfully filled in and submitted surveys are counted in real time, and the corresponding statistical results are continuously updated on-screen.

In response to questions regarding the expedited changes that jolts of cultural prestige may impose on a neighborhood, SI’s director, Simon Castets, offered a two-fold explanation of why he considers the institution’s presence to be roundly positive. Noting the unarguable reality that the Institute has physically replaced what had always been a bank since the building was erected in 1954, Castets explained how certain shifts in programming — for example, the introduction of SI ONSITE in addition to new educational initiatives that acknowledge a perhaps broader audience than before — are being formulated in close conjunction with participating artists, in keeping with the Institute’s remit as “a space for artists, by artists.” Transparency is the intended effect here. As Castets explained, “SI’s artist-led education programs take place in a dedicated Education & Public Programs space, and provide opportunities for families with children, teenagers, university students, and seniors. These education programs are unique in that artists — either in current, past, or forthcoming exhibitions — are at the center of the workshops, directly driving forward dialogue and experiences in art-making together with a core group of teaching artists.” SI’s inaugural education partners include GO Project, Little Missionary’s Sara Curry Preschool, Sirovich Center for Balanced Living, and School of the Future. Free admission is also a major aspect of this effort to accommodate a wider public.

The East Village has been an active site of cultural production and presentation since its heyday in the 1980s. While there are surely identifiable distinctions between the stark appearance of a multi-million dollar building and the outcrop of small hubs of commercial galleries, the picture does begin to change when not only higher-end galleries proliferate, but also museums and prestigious nonprofits with dedicated, large-scale donors. This shift may be described as a reconfigured network, equally as dense as before, but whose main players are no longer the artists. Patrons and executive-level staff are the substantive forces present and at work.

Connecting back to the readymade as an inaugural exhibition theme — and as a potential ideological marker of the institution’s intended long-term ethos — there is a trickiness to navigating this conceptual foundation relative to what art can accomplish within society. Those who are not especially steeped in visual art can tend to be alienated by such work, which they see as fundamentally elevated in an exclusionary way. But this irresolvable dilemma has been at least acknowledged by Fischli and Olsen’s title for the show, which is something of a readymade itself. A footnote as footprint of the mysteriously self-disavowing French artist Philippe Thomas’s fictional public relations agency readymades belong to everyone®, active from 1987 until his death in 1995, the title as slogan speaks a simple yet contradictory truth.

An excerpt from the accompanying text for Project Native Informant’s 2016 exhibition “Philippe Thomas with Interventions by Bernadette Corporation, DIS and Emily Segal” reads as an expanded homage to the artist: “The reason why readymades belong to everyone is certainly not because everyone can become a collector, but because everyone can make themselves sensitive to the potential, to the possibility harbored by every vulgar mass-manufactured object to be or not to be a work of art. Everything can become a readymade, anyone can be an artist; it is enough just to develop the sensibility that allows one to unmask, behind social classes, the almost physiological universality of the ‘whatever-singularity,’ which in our societies only appears in debased form in total institutions, in the form of naked life.”

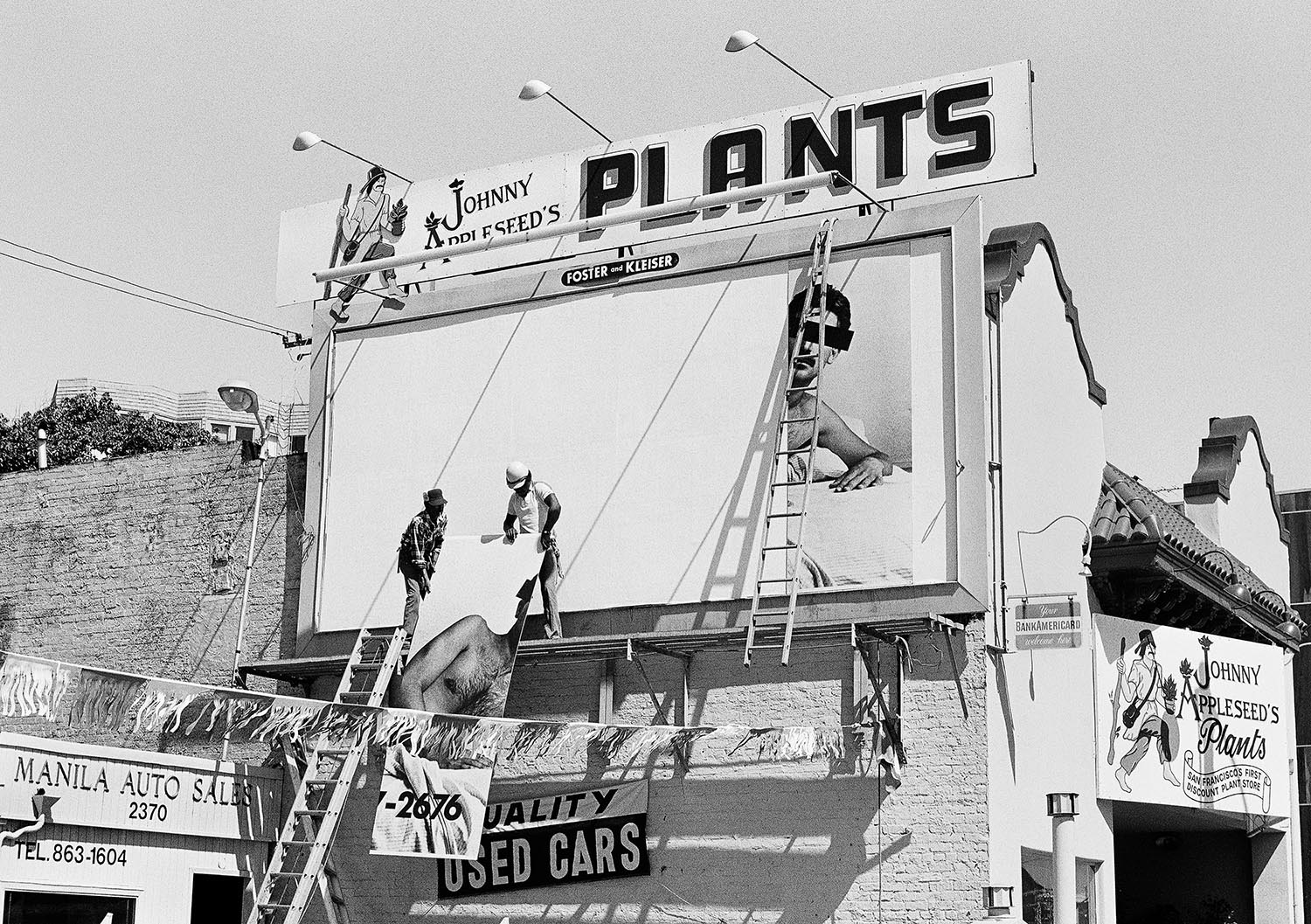

Thomas had created the agency as a bureaucratic entity through which the rights of authorship would pass, dissolve, then rematerialize as credited to another person entirely, namely its buyer. Housed in Cable Gallery in New York (also on Wooster Street during its days of operation), visitors would encounter Thomas sitting behind a desk surrounded by plants — evoking the atmosphere of a 1980s office suite or a Marcel Broodthaers décor — as well as advertisements for the agency and works waiting anonymously for their prospective authors.