“We will fail. But we will try.” Wandering through the streets of Athens, I read these words in the much-leafed-through pages of my About Documenta 14 pamphlet. The words rightly address the difficulty of harnessing coherent, critical agency amid such a mega exhibition. Pursuing a politicized reading of our present moment and its attendant histories, Artistic Director Adam Szymczyk cited “unlearning” — a play on the working title “Learning from Athens” — as a way to enter into an exhibition that attempts to sidestep any hegemonic narratives and allow space for manifold approaches and multilayered, unfolding interpretations.

And yet, from the word go at the press conference, where Jani Christou’s Epicycle (1968/2017) was performed by the participating artists and the curatorial team, who hissed, wailed and stamped their feet like a group of wild, untameable animals (being conducted by a white man), it was difficult to glean any clear methodology.

Spanning four main venues — the Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST), the Benaki Museum – Pireos Street Annexe and the Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA) — with additional performances and happenings taking place throughout the city, the exhibition offers hundreds of works to write about.

Originally founded in 1871 as a musical institution, the Athens Conservatoire (Odeion) features projects by artists who deal with sound or reconsider its use-value. Susan Hiller’s video work The Last Silent Movie (2007) draws visitors into a pitch-black space where, sitting in old-fashioned cinema stalls, they listen to archival recordings of extinct and endangered languages. Understood only as variants of noise, pitch, tone and vibration, a constellation of dying communication is mapped, the supernova before the ultimate silencing of these minority groups. In Nevin Aladağ’s Music Room (Athens) (2017), performers play musical instruments constructed from furniture: stools as drums; sofas plucked as guitars; chair cellos; metal tables adorned with bells to shrill effect. She references tarantism, mainly practiced by women who “dance away the pain of any poison.” Yet as people observed the performance, no one danced, choosing to soak up the experience with passive eyes rather than active bodies.

Archival materials from the Scratch Orchestra are presented nearby (an example of Documenta, true to form, offering up hidden histories but making them feel didactic and dry, boxed in vitrines). This musical community, representing varying levels of expertise, formed in 1969 in London to perform music “from scratch,” often based on written instructions and graphic scores. Daniel Knorr’s performative installation Materialization (2017), in which a mountain of detritus from the streets of Athens is pressed, object by object, into books for visitors, feels like an overliteral and sentimental spectacle of what we might “take away” from Athens. More subversive are the instruments made (and played) by Mexican artist Guillermo Galindo, also comprising discarded matter. These odes to border crossings use plastic combs, water bottles and boat parts to reference how Mesoamerican peoples saw instruments as talismans for movement between worlds.

Nigerian Emeka Ogboh’s The Way of Earthly Things Are Going (2017) wraps an amphitheater-of-sorts within a sonorous landscape, transforming data into musical scores from documents about financial crises from 1929 to the present day. A real-time LED display of world stock indexes runs simultaneously, its bright red and green digits charting the world of finance, which feels jarringly stark amid the ambient sounds. Performances at the Conservatoire abounded, including Haitian choreographer Kettly Noël’s Zombification (2017), in which puppets made from hessian bags and ropes have mirror-panel visages reflecting the viewer’s own face; these voodoo figures move as zombies within a bamboo-stick installation, seen as “nonfolkloric figures responsible for current, real, globalized violence.” And they’ve got our faces.

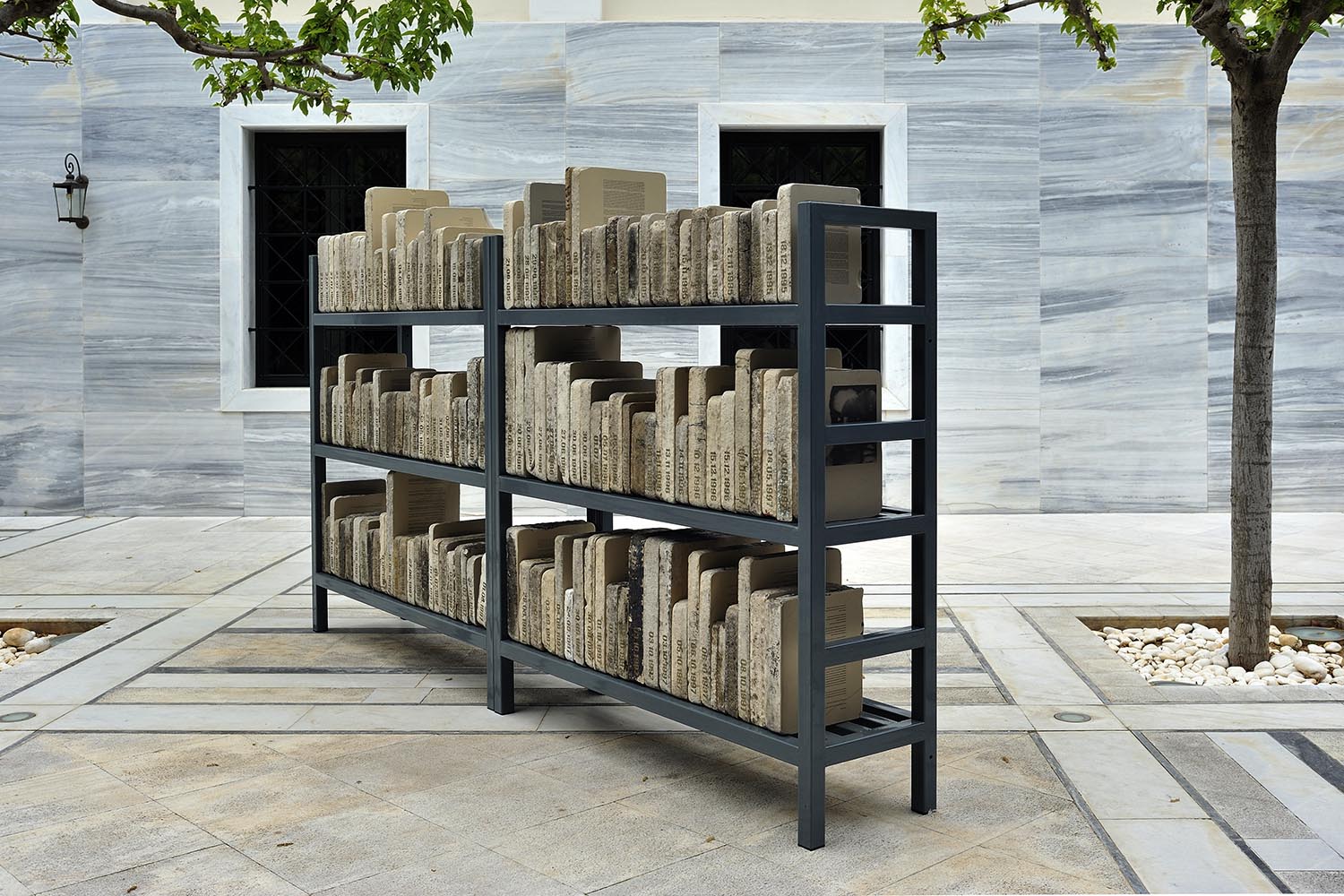

The National Museum of Contemporary Art, housed in a former brewery that was abandoned in 1982, has only recently reopened after a long-term reconstruction project. Nigerian Olu Oguibe’s Biafra Time Capsule (2017) reflects present-day narratives of displacement through books, photographs and magazines representing the human tragedy experienced by Biafra during the 1960s Nigerian civil war. French filmmaker Michel Auder’s Gulf War TV War Untitled (1991, edited 2017) depicts him filming his TV while constantly changing channels. I was reminded of my own 1990s childhood, when I sat and stared and flipped past the static between stations, from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to news reports on George H. W. Bush’s “Operation Desert Storm” in Iraq to easy-to-watch commercials.

Chilean Cecilia Vicuña’s sculpture Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens) (2017) suspends thick masses of knotted red wool from a circular metal frame. Reminiscent of umbilical cords, blood or even matted hair, quipu was originally an Incan system for recording events with knotted strings. Here, the poet Vicuña symbolically suggests the joining of word, narrative history and flesh as we imagine the bloodshed of past regimes, including Chile’s Pinochet, which resonates with today’s landscape of war and brutality.

On Pireos Street, the Benaki Museum seeks to investigate untold, unfinished or overshadowed histories. Israeli artist Roee Rosen fictionalizes the life of Eva Braun (Live and Die as Eva Braun, 1995–97), writing texts that place the reader in the subjective position of Hitler’s wife. This does two things: make us see Braun as human, and reminds us that we too are emotional, fallible and capable of committing evils. The standout work is Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s somniloquies (2017). A seventy-minute film of hazy, indistinguishable body parts, as if seen through squinting eyes in a dream, is overlaid with 1960s recordings of the world’s most prolific sleep-talker, American musician Dion McGregor. His descriptions veer from being cruel to intriguing and sometimes funny, as extreme sexual scenarios are interspersed with the sounds of snoring. Though the histories we amass in our dreams are often lost to the night, here we experience a half-open window onto that world.

Projects at the Athens School of Fine Arts (where one could also visit the studios of students) supposedly address notions of creativity and educational experimentation. Photographs, magazine articles and texts about Anna and Lawrence Halprin’s dance deck (on the hills outside San Francisco), where innovative dance pieces and improvisations took shape in the 1960s, reinforce current rereadings of the history of Minimalism, inserting dance and movement into the story. Artur Źmijewski’s film Glimpse (2016–17) is a staged documentary depicting the refugee camps of Berlin and Calais. The artist paints men’s faces white, marks their clothes with crosses and gives them new shoes. Although Źmijewski raises important questions regarding the place of art in the world and its impact on our reality, his work here feels both patronizing and exploitative.

The first chapter of Documenta 14 in Athens poses an open-ended question regarding what art can be during times of economic and humanitarian crisis. What it doesn’t answer is what art can ever really do, or where the agency of this exhibition lies (and the subsequent use-value of its €37 million budget). In an open letter about artist and refugee evictions as implemented by the city of Athens, written by the local activist group Artists Against Evictions to Documenta 14 visitors, they urge: “You say you want to learn from Athens, well first open your eyes to the city and listen to the streets.” The exhibition is complex and obfuscated, just like the world in which we live, and at times it’s hard to tell what is happening and why — again, an excellent reflection of our times. But we need more than a mirror image. Culture can do more, has done more, and should strive to stimulate social change. By reflecting a complicated world within which we’re already becoming lost, it feels as if the many voices of the artists in the exhibition drown one another out. We are left “condemned to roam, without repose.”¹