In the Chinese philosophical system known as feng shui, literally wind and water, qi, the metaphysical force of unity, is carried and dispersed on the wind. Water brings qi to rest. In the 11th Shanghai Biennale there are many such light breezes, enhancing works that play on all the senses.

These include Yin Yi’s Ocean Wave (2016), a tight cluster of electric fans at the entrance that rhythmically switch on and off. The image of water, in the form of the video Flag (Thames) (2016), turns out to be fake; it is a year-long computer simulation in which the artist, John Gerrard, has included a large patch of iridescent oil that smothers the restlessly moving surface.

The notion of agitated movement is in keeping with a remark at the opening reception by Monica Narula of the curatorial team Raqs Media Collective: “The work of art is an antidote to the poison of inevitability.” The suggestion is of an urgent need to administer a cure. Throughout the exhibition, wall texts describe the works in the present tense, as actions. The curators frame the exhibition as a quest “to discover, transmit and learn…” The titular question “Why Not Ask Again” resonates with Vladimir Lenin’s title “What Is To Be Done?” Lenin’s essay outlines a problem and opines a program for change. Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s novel, from which Lenin borrowed his question, fleshes out an ideological way of living. In this exhibition uneasy questions are proffered—but no answers are suggested.

Many works create ambiances with odor, surface texture, motion, illumination or proximity, making these elements just as important as sound and vision. For example, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu’s So Far (2016) presents a whiff of mineral fuel amid two forklifts arranged face-to-face in a tug of war. They are parked close to the entrance of the Power Station of Art, the Biennale’s primary site, so that they obstruct access to the vast atrium. Three sealed eggs, composed of ceramic crocks joined by their rims, are braced in chains between the trucks. The drama implied refers to Otto von Guericke’s experiment demonstrating atmospheric pressure. This was spectacularly performed in 1654 when thirty horses attempted to separate two copper hemispheres with a vacuum inside. The current work is even more elaborate, yet by replacing the hot bodies of sixteen snorting horses with cold machines, and the plasticity of copper with vitrified material and silicone sealant, the awe of grasping the science of air pressure is dissipated. Gone too is the culture of labor that later led the Levi’s jeans brand to use a logo depicting horses pitted against the resilience of the company’s product, likely inspired by an image of the experiment. So Far is a memorial to praxis. But, today visitors cannot enter through the implied arch; they have to go around.

If an ethos of manual work can be evoked by representations of tools, in this case the tools have all been laid down. In As Long as You Work Hard (2013) by Cell Art Group, a dense constellation of hand tools are embedded in a wall of steel; in Susanne Kriemann’s Pechblende (2016), “miner’s objects” lie inert within dim projections; or in Vinu V.V.’s Noon Rest (2014), sickles are impaled in a tree. These are final acts, job done—everyone gone.

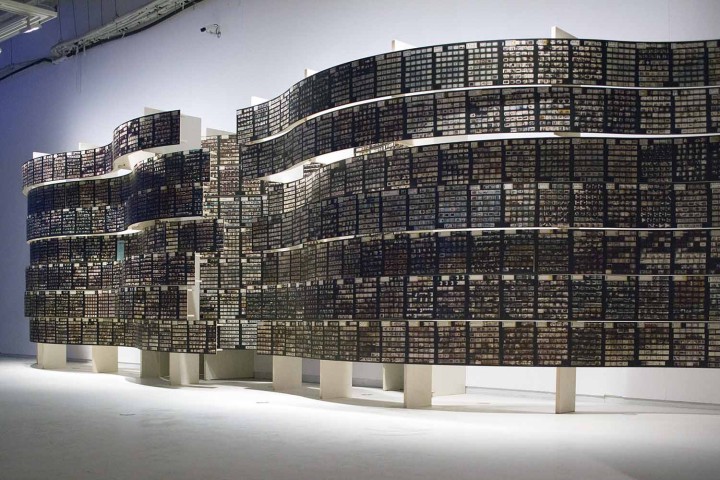

Life doesn’t flourish in this exhibition. In Caparazón (2010), Regina José Galindo peacefully curls up in a protective double-skinned plastic bubble, only to be subjected to a percussive assault from a small baton-wielding mob. Spiders and bees endure in the works of Tomás Saraceno and MouSen+MSG, but their citadels are frail and can easily be eradicated by thoughtless fingers or casual boots. Presence is mainly in traces, such as the washing left to dry on a fighter jet, a public monument in Lahore, in Ayesha Jatoi’s Clothes Line (2006); or in Georges Adéagbo’s extensive array of objects and artifacts, “The Revolution and the Revolutions”…! (2016).

“Why Not Ask Again” yearns for the future, but many of the artworks look back quizzically, passively or with humor to show how the past buffets and fractures the present. YoHA (Graham Hardwood & Matsuko Yokokoji) provide a notable exception. Plastic Raft of Lampedusa (2016) is a meticulously dismantled inflatable boat. The fileted rubber craft inevitably speaks of the exhausted desperation of migrants. There is some hope here. It would be an arduous and complex task to put it back together, but not impossible. A few artists try new ways to fit the pieces together, to persevere and to restore balance.