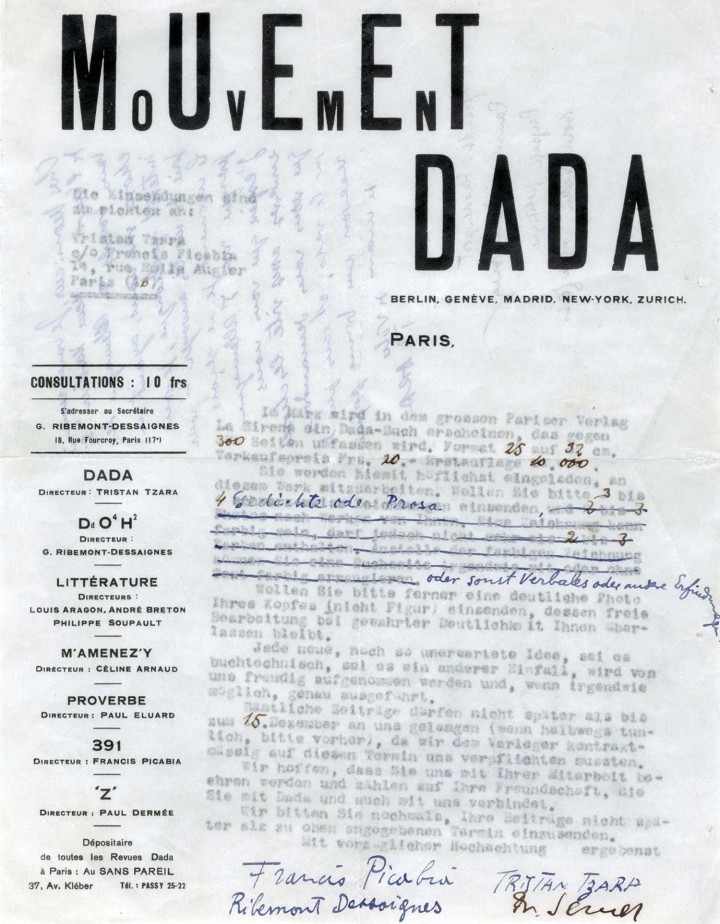

Cutting across national borders erected in the aftermath of World War I, Tristan Tzara’s publication Dadaglobe was to be the definitive statement of the Dada experiment begun five years earlier in Zurich, before it unraveled in a mix of interpersonal arguments and financial problems.

This historical jewel of an exhibition, helmed by Adrian Sudhalter, brings together the original correspondence and responses to Tzara’s call for reproductions, portraits, layouts, texts and original works. It’s a dense hanging where everything, from John Heartfield’s sensual and shirtless Double Portrait of Johannes Baader and Raoul Hausmann (1919) to Max Ernst’s small collages, like Chinese Nightingale (1920), is worth lingering over. Why aren’t all historical exhibitions this rich and stimulating?

Literally arranged along colored territorial lines, the exhibition presents Tzara’s project as illustrative of a shattered postwar Europe that still held creative possibilities. As Europe today questions the free movement its union has allowed, it’s important to once again note the cultural costs of geographic segregation. Kurt Schwitters, holed off in Hanover, Germany, was only able to send photographs of assemblage and collage works. They’re beautiful, low-contrast images that show how cognizant Schwitters was of the importance of reproduction in its own right —especially considering his remote situation.

A real highlight is Theo van Doesburg’s response to Tzara’s call. Stating that, as the founder of DeStijl, he could not possibly participate in a movement that was the antithesis to his, he instead submitted under his Dada pen name, I.K. Bonset. Portrait of I.K. Bonset (1921) shows the back of van Doesburg with a textual halo, written in pen, surrounding his head: Je suis contre tout et tous. I am against everything.