Elysia Crampton is a producer who has lived and worked under many names. She has influenced a whole generation of artists with her hectic musical collages that reference traditional Andean music (among many, many other things). Her first “official” album, American Drift, recently released on FaltyDL’s Blueberry Records, is finally getting her work the attention it deserves.

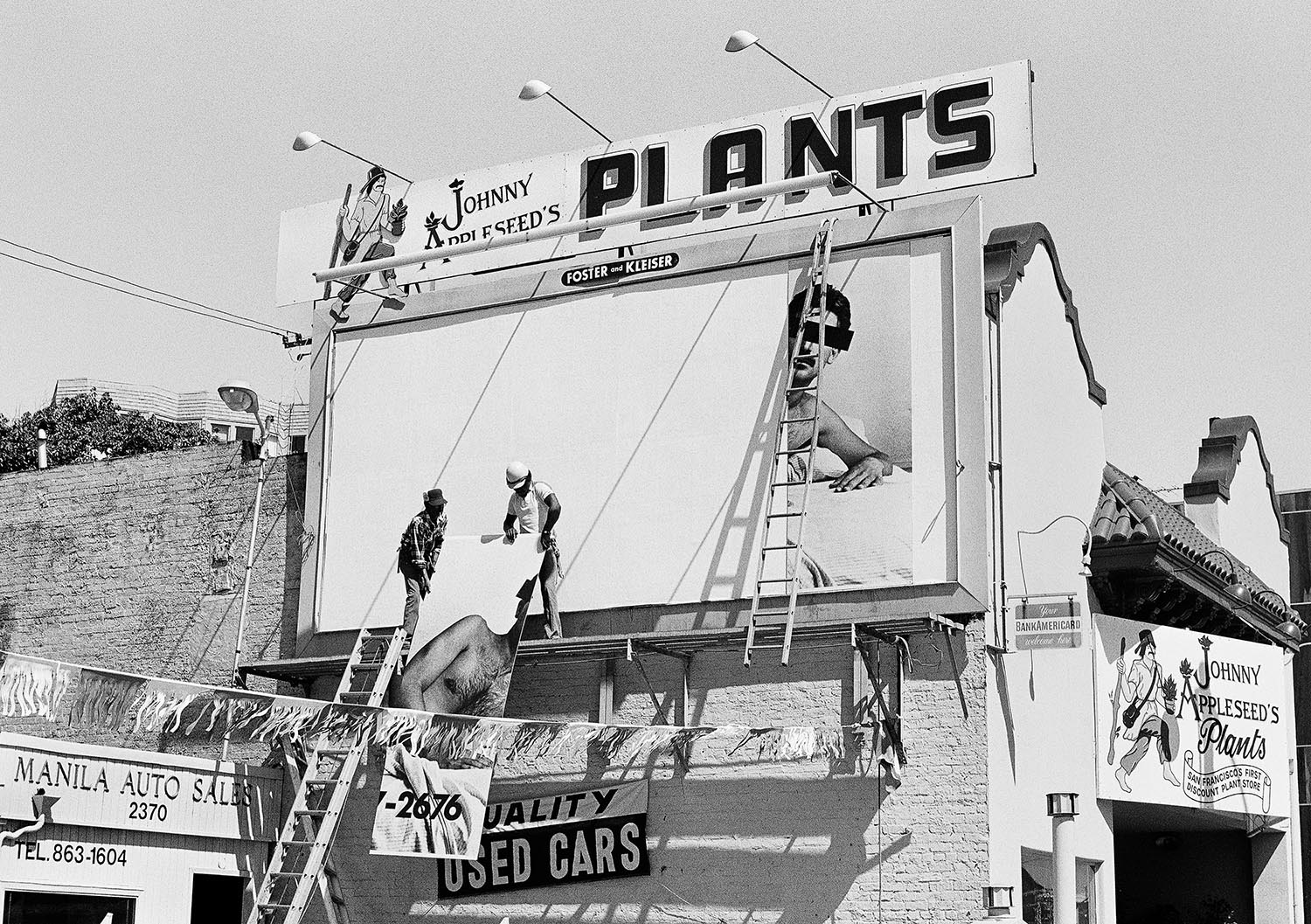

Until recently working under the moniker E+E, Crampton’s current incarnation is the product of what she calls a “born-again experience.” She’s a Bolivian-American who’s lived in Mexico, California and Virginia, and is now revisiting her roots as a self-identifying mestiza artist in the seclusion of a small farm in the Bolivian province of Pacajes. In the interview that follows, the artist expounds on queer indigenous histories, music as texture and her newfound trans-spirituality.

What is your musical background? You’ve said that you’ve not yet had a higher education.

I went to college but I studied sociology and I never got my degree. Before that I was in an art school and I studied fine art. It was very “art school,” so it was very much about design, and I think that got translated in my music. I still look at it like painting. In fact, if I didn’t [do music] I probably would still be painting because I love painting. Especially with mediums like gouache and oil, the texture of it, the oils, mixing the colors. But also with my background and my love for writing, I approach music that way. I construct songs in the way you would put a paragraph or a sentence together. There are pauses, there are whole sections of cumbia predicates and huayño subjects.

Spanish is your first language but English is now your primary one. As a person with an indigenous heritage, what’s it like having these two languages that you might not be so connected to?

On the farm I’ve been living at, in Rosario, everyone speaks Aymara. And maybe I know five words in Aymara. This is my problem: I’ve been very vocal about identifying as mestiza, but I always see it as being an intersection, identifying as brown. Obviously there are mestizas who have white privilege — they can pass as white. But I feel like there’s no other word for me right now that can acknowledge not only the splits and the tensions of what makes me who I am, but also acknowledges that before the white, Anglo-American side there’s already that split, that battle between [being] Spanish and indigenous.

I’ve been living now in my great-uncle’s old room, and right above the bed there’s this painting of Bartolina Sisa, which is a famous indigenous woman. She’s famous for a number of reasons. [There are] stories with the indigenous [Wiphala] flag, which later kind of became the gay flag, like an early form of a rainbow flag. She has a very violent story as part of the indigenous revolution. They captured her and they cut her up and they sent her body parts around, almost like a saint. I never read up on what happened to her body parts, if they’re in churches now or some fucked-up thing like that. But I’m just thinking about her, and her body, and the power of that. About her being split into pieces like that.

When you talk about identifying as mestiza and living between Bolivia and the US, while also having recently transitioned, it feels like you literally embody all these splits and tensions.

I’m trying to develop a new language for this too, my external transition, with it being very connected to this “born-again experience” I had. I don’t want to call it religious, but I guess it is kind of religious. I’ve been trying to understand the implications of that type of trans-spirituality that I’ve experienced, the political implications of that, [to] also sort of reclaim my whole life, my whole person, because obviously I’ve been trans my whole life. I’ve been queer my whole life. [It’s] something that reclaimed me even before I identified as trans.

Your transition was quite recent, like a few years ago?

I was traveling a lot. I started traveling more to Bolivia again, and it was actually being back on the farm in Rosario that was the last straw for me. That was the moment. It wasn’t even like, “I’m going to be trans.” The night sky is so clear there. It’s like any desert where you see that depth of space. I was thinking about indigeneity, and astral birth, and of being a star and all this dis-anthropocentric stuff. I had this little fire there and I bowed my head and that was that. I remember coming back to the US and I just started filling out the papers. For once I stopped cutting my hair and I haven’t cut it since.