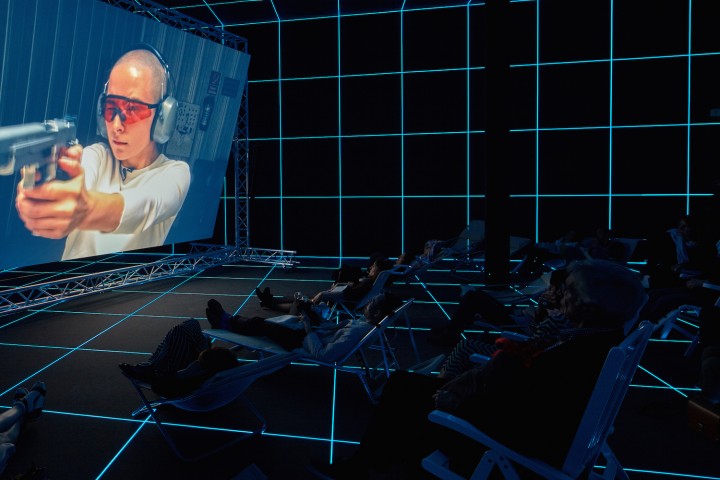

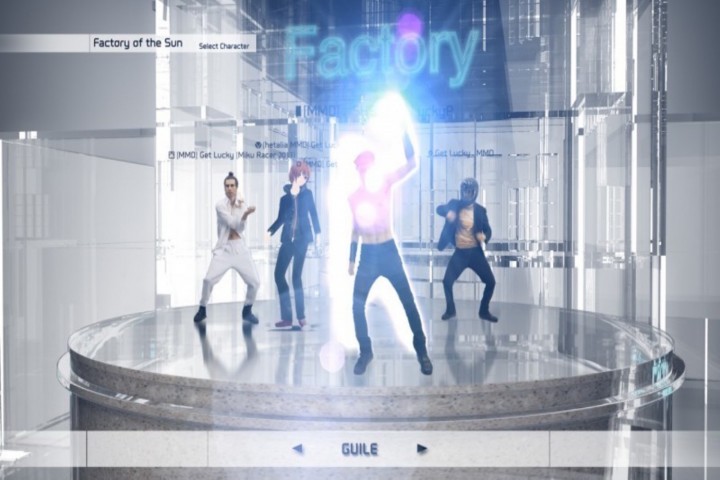

The state of the world is mapped out in every direction in Venice. The national pavilions that dot the perimeter of the main exhibition spaces present alternate histories and futures, and offer respite from the dark prognoses and black, inky palette of “All the World’s Futures.” Against the darkness are scorching crimson highlights, like the blood-red walls bordering the “ARENA,” a theater nested inside the Giardini and designed for the nonstop oration of Das Kapital, Karl Marx’s singular 1867 critique of capitalism, running well over a thousand pages long. Down in the blacked-out cellar of the German Pavilion, Hito Steyerl’s film The Factory of the Sun screens amid a grid-like installation of blue neon rays cast over the entirety of the space in three dimensions. An apt background for the video-game aesthetics of the film, this two-dimensional world slickly assuages alienated users. Looking on, we know that the situation is inevitably rigged, and this position of knowing resignation is explored in the laser-sharp interstices of gold lamé-covered amateur YouTube dance stars; avatar customization options in video-game introductions, providing identity and expression through a series of multiple-choice options; and poseur fiscal and political experts who testify to the neoliberal agenda in staged segments, filmed to be looped on cable news channels. A blaring disco soundtrack is the only suitable transition between the absurd scenes.

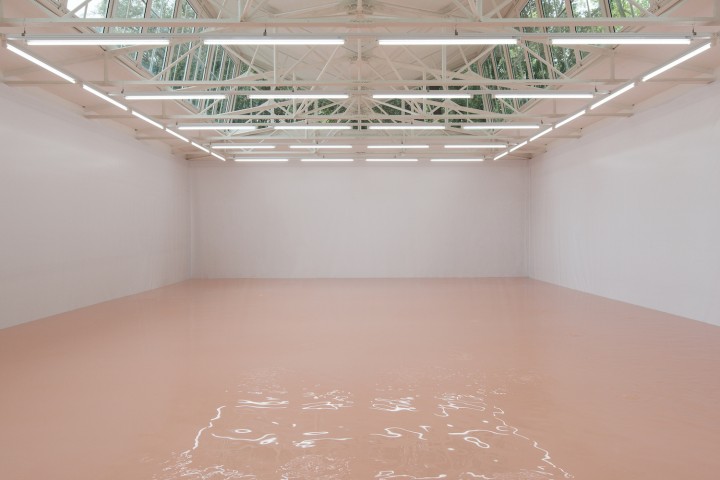

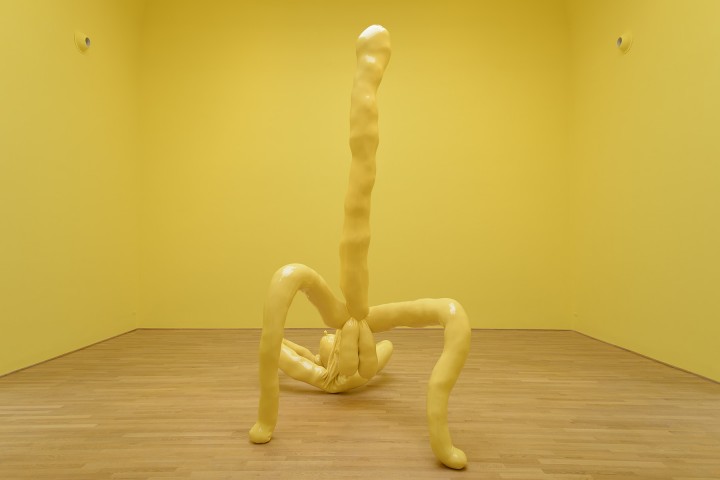

After readjusting to sunlight, one enters the relentless margarine interior of the British Pavilion, populated with Sarah Lucas’s partial figures, cement-colored mannequin bottom halves alternately draped over mid-century office furniture and having fun with cigarettes. The cheeky exhibition, titled “I SCREAM DADDIO,” was appropriately inaugurated with a metal band performing on the Pavilion steps. Nearby, the chewing-gum pastels and teenage girl’s bedroom color scheme of Pamela Rosenkranz’s Our Product in the Swiss Pavilion radiate an uneasy sedation. An entry foyer of spearmint green leads into a tepid pink grand space; the undeniable artificiality of both rooms hints at the unsatisfying placation we experience via nonstop consumption, and the attainment of wellness and satisfaction that targeted marketing promises us. Together, triumphs in chemistry, sophisticated engineering and market research hold us in their plastic glaze, suggesting that we are as fluid and malleable as her blush pool of Evian water, silicone and diluted pharmaceutical drugs.

These various manipulations of color and light segue to Turkey’s Pavilion, its new space taken over by Sarkis, the Armenian artist originally from Turkey. Respiro is an airy occupation of the Pavilion anchored by a neon rainbow arching at each end; seven nervous lines of pure pigment are illuminated while a soundtrack by Jacopo Baboni-Schilingi floats through the stained-glass windows. A circle of children’s fingerprints in paint decorates each side of a mirrored wall in the center of the space. Respiro quietly came to life as the centerpiece of a constellation of Sarkis installations in dialogue, as six other institutions, including the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam and the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Geneva, opened exhibitions by the artist that act as “messenger sites.” Reaching back millions of years to describe the very first rainbow, what the artist has described as the “the breaking point of light,” the spirited formation was helplessly optimistic and piercingly radiant, a healing gesture on the centennial of the Armenian genocide.

Norway, this year the sole commissioner of the Nordic Pavilion, with its spare, sand-hued Scandinavian design, staged a performance by Camille Norment, an American residing in Oslo. In her subtly arranged Rapture, the artist lead a trio of musicians while playing a glass harmonica. Her cloaked approach delivered a political and interpersonal metaphor: dissonance does not go unnoticed. The oversize window panes lining the pavilion appeared to be shaken and dislocated by the music’s vibrations, their sharp corners fanned out in stacks over the floor and lawn. Next door, the American Pavilion’s film installation by Joan Jonas, They came to us without a word, was enveloped by simple drawings of animals on large white sheets of paper hung neatly on every available wall. Screening tribes of bees buoyed in amber pools of honey and children engaging in theater, the films were supported by pure white cones and hand-shaped spheres, reflected among the elegant chandeliers and mirror panels. The sun-bleached ambience reflects Jonas’s mixture of nostalgia and innocence as embodied by the use of child performers in her films as well as the artist’s shamanistic spiritual wanderings. Given the American Pavilion’s proximity to the dark panels by Oscar Murillo flying half-mast over the main exhibition’s entrance, a contrasting perspective on our collective future is inevitable; the distinction lies in our depth of field.