I usually say that an exhibition is not a book on the walls. For once, I was wrong. Zoe Leonard’s show is a book that runs over the walls — a book about a river, which exists despite walls.

The project, begun in 2016, is ambitious, and monumental, in the etymological sense: in other words, it “makes you think.” The work is double, triple even, in that it comprises a set of more than three hundred photographic plates. Hung according to the protocol established by the artist, under glass held by pins, the images have a white margin and a black border-frame. This systematic fine edge signifies that the artist is presenting not the vision of the world but her own point of view on the world. “Not the world but my view of the world,” she said at the book’s presentation.

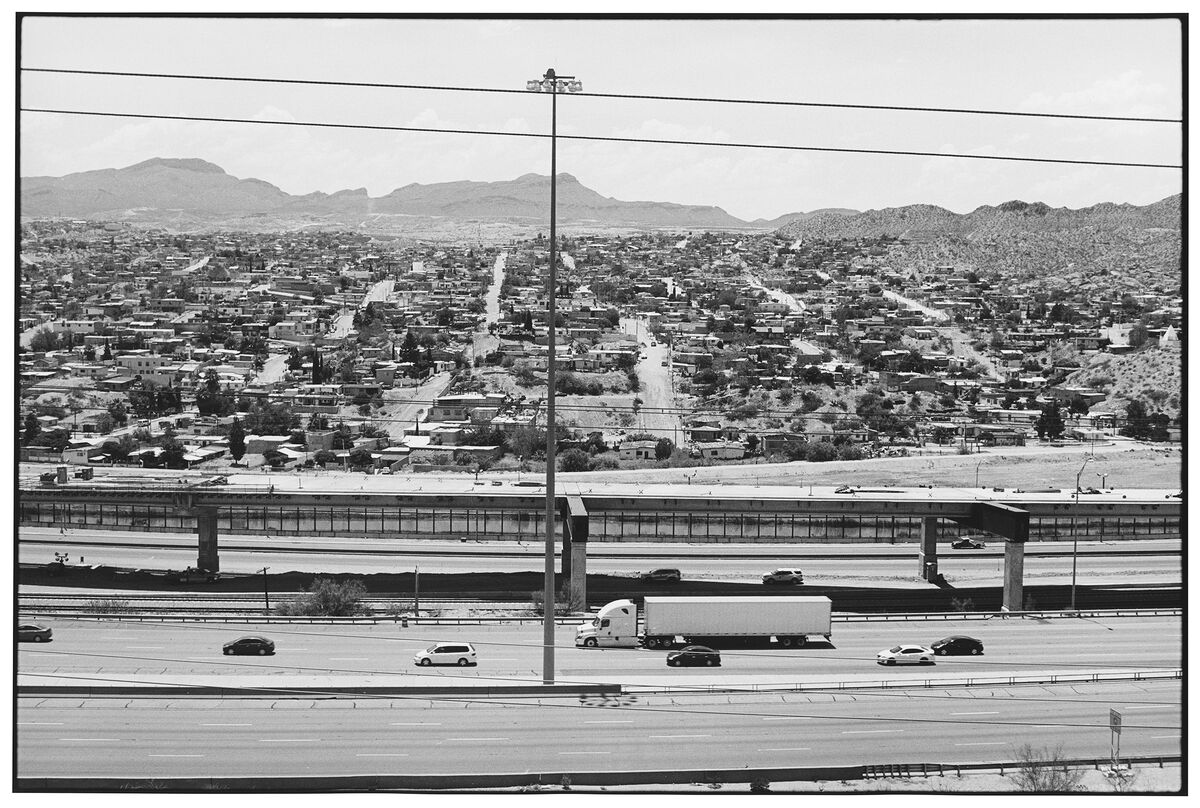

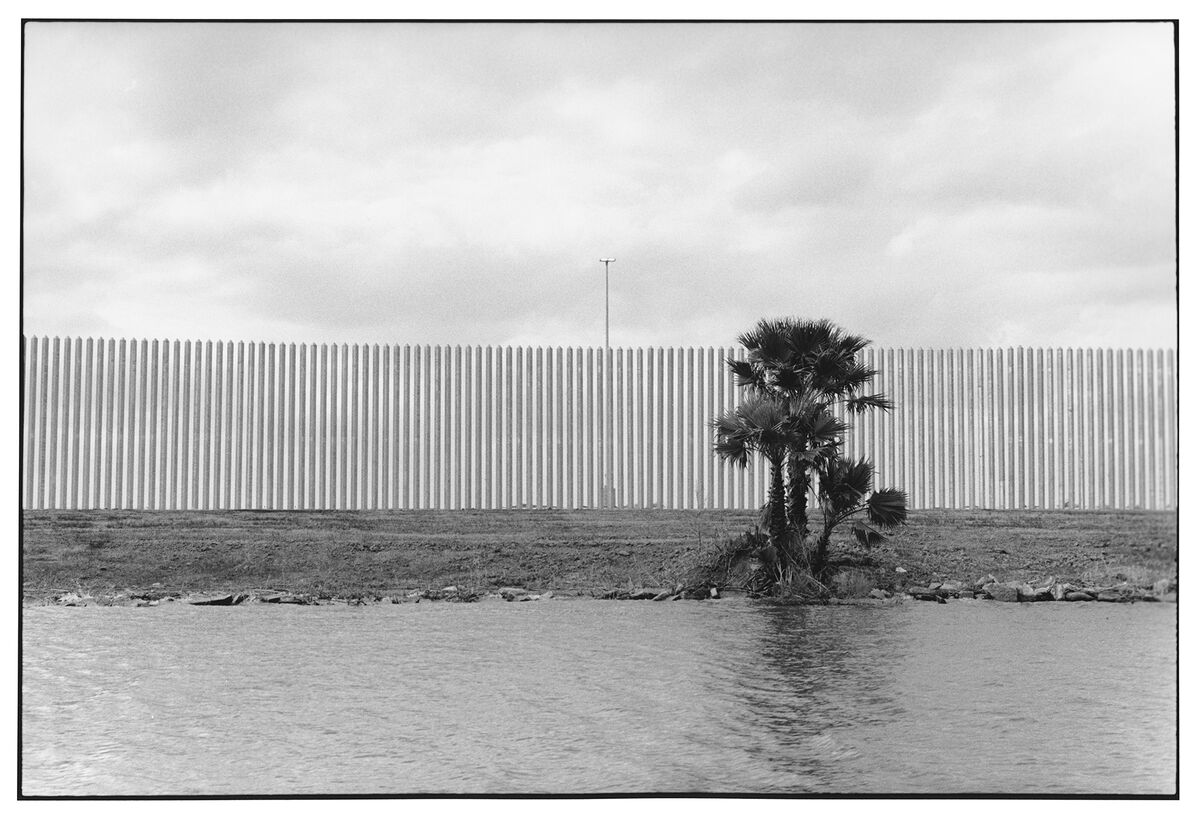

That subjectivity is important; it designates the act of taking a picture as taking a position. And indeed, the survey of hundreds of kilometers along the Rio Grande locates the procedure between several visible and invisible frontiers. One is signified by the intermittent “wall,” in concrete or metal, sometimes on private land, sometimes public. Added to the real wall are the metal structures, begun back in the nineteenth century, and the falsely common spaces, such as parking lots and service stations. In those rest areas you often observe very different activities depending on whether you are on the US or the Mexican side of the border. On the Mexican side you see people playing and bathing in the river; on the US side, it is very often, if not always, a commercial activity or an object of control. A patrol car, in particular, is an index, a “punctum” that makes me an observing subject, a witness. The other frontiers are those of languages. There are five languages: the two official ones, English and Spanish, and then the French of certain texts in the book. But we also find Mohave: “Inyech ‘Aha Makavch ithuum” (The river runs through the middle of my body). It is not a metaphor, the author Natalie Diaz points out.1

And then there is the language of the actual photograph, whose poetics Zoe Leonard reveals: “How forms of language communicate as any individual form of grammar […] photography has linguistics, tones, contrasts, a vocabulary, shapes, format,” she says.2 So it is that the deployment of the work “alongside” the river is structural, as it enables us to become simultaneously aware of several stories.

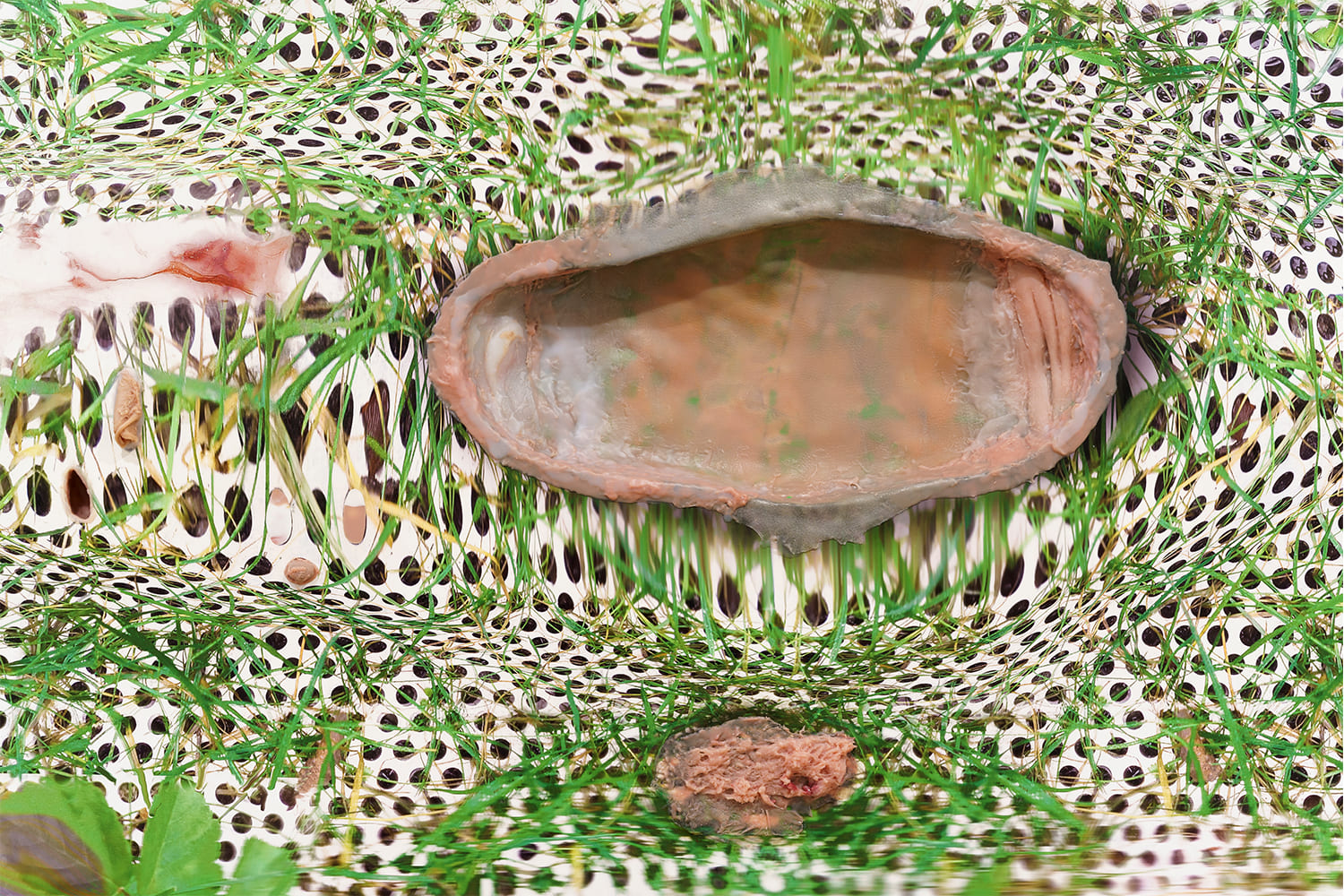

The photographic act is not limited to the click of the shutter; it is the whole experience of the survey, the choice of location, continued in the choice of frame, the margin, and the book in which the river is displayed again. A frontier has at least four edges, each side with two borders, like the black fringes and white margins of the image. In each photo we rediscover the history of photography. Carleton Watkins’s landscapes of Yosemite Park, Walker Evans’s photographic campaigns for the New Deal, Diane Arbus’s intimate portraits. The subtle grays of the black-and-white prints speak of all the meticulous printing work, which in turn testifies to the almost archaeological patience of the photographic project. We are in a present that is not datable in days or hours, but in a space-time which is that of the invention of photography itself. So much do the constructions (bridges, roads, electric pylons, buildings, and so on) speak of modernity and thereby its secret conquest of lands that were autonomous before they were autochthonous. Their natural power is there, the heritage endures, beneath, like a slow abrasion. The river is not a metaphor, it is a living entity, and all its different strata and voices form a portrait in motion. It is not just flowing water but mud, earth, drained by whirlpools: vortices depicted in shots close together which provisionally open and round off the exhibition, the commotion or hurly-burly at the origin of every creative act: that of standing and performing one’s medium while upsetting the rules of one’s support. So it is that every photograph is “always-already,” a post-performance,3 the negative being the score and the print the performance itself.4