Wong Ping’s practice revolves around three fundamental aspects — filmmaking, sculpture, and storytelling. His animated films are the result of time spent working as a digital editor for a TV station in his native Hong Kong. They are conspicuous for their very elementary yet appealing visual language, and, in the best cartoon tradition, many are able to transform potentially explosive or discordant subjects into something strangely endearing. His sculptures mostly stem from his films, and are a mixed bag of ready-made objects (such as the pile of more than four thousand toy gold dentures in The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetery) and site-specific installations that pop up where you least expect them, cultivating an ambiguous yet thoroughly integrated relationship with their surroundings. This is the case, for example, with the large brick column that breaks through the ceiling of the Camden Arts Centre’s reading room, only to resurface on the rooftop as a towering, convoluted red heart.

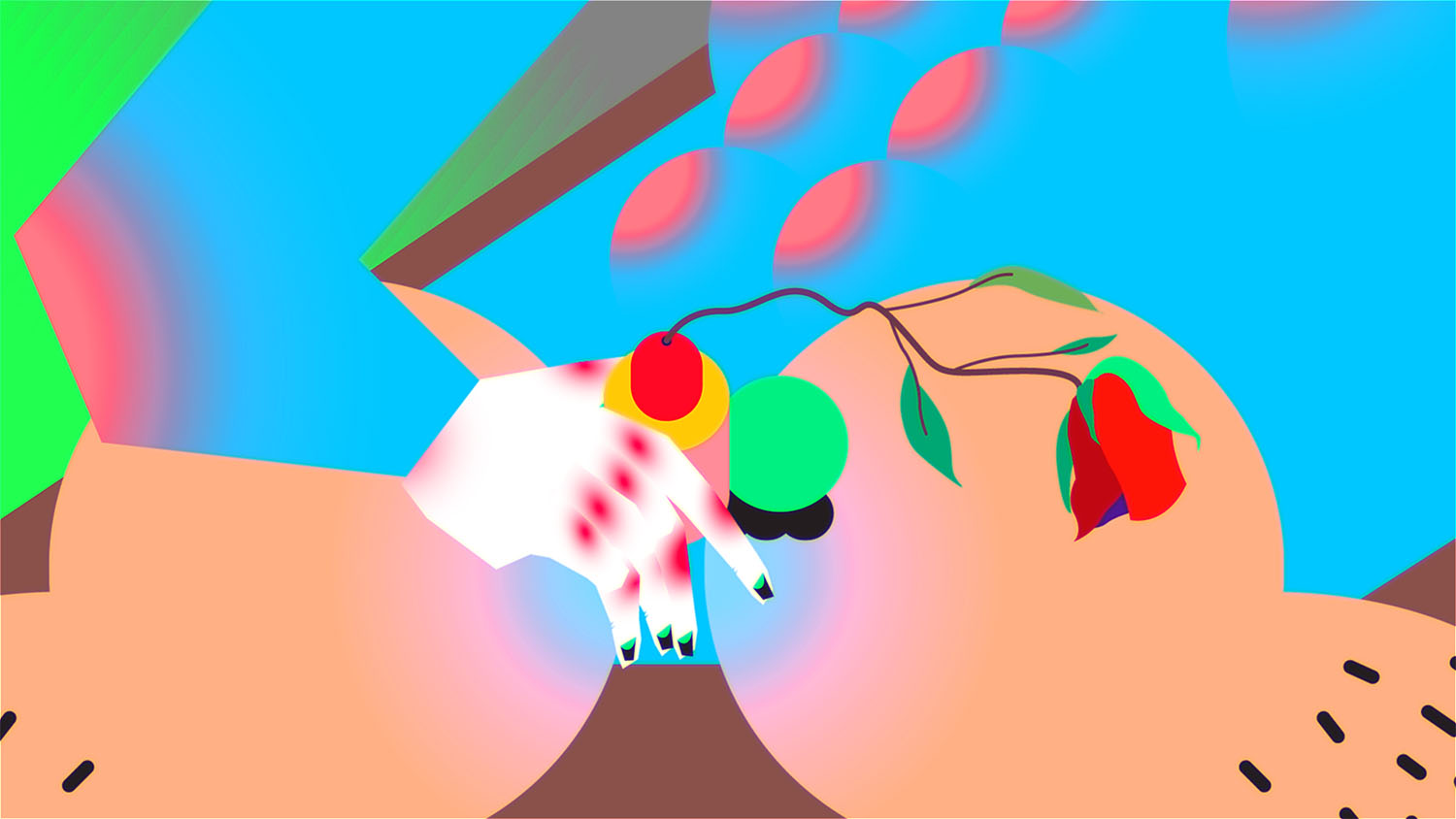

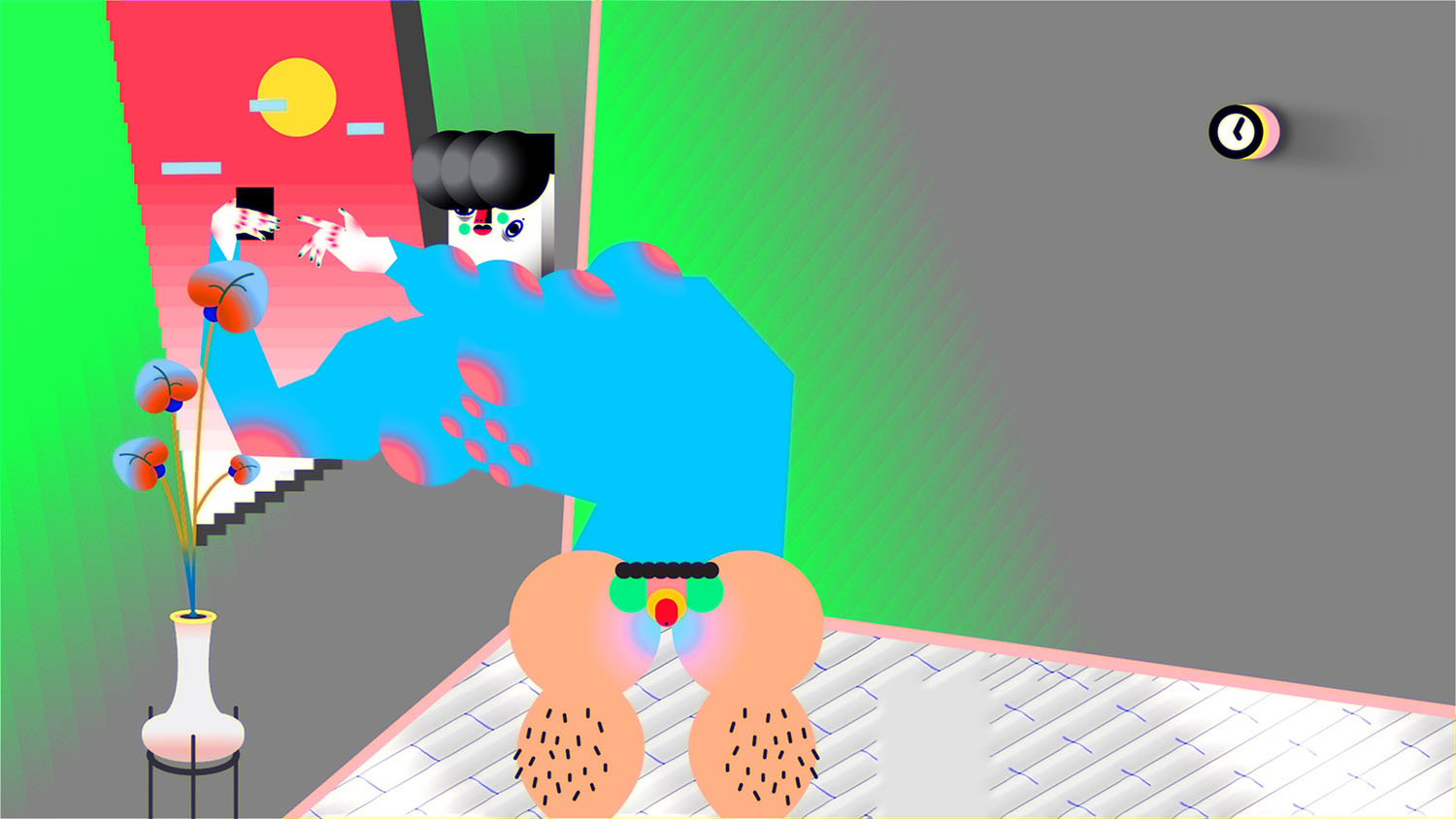

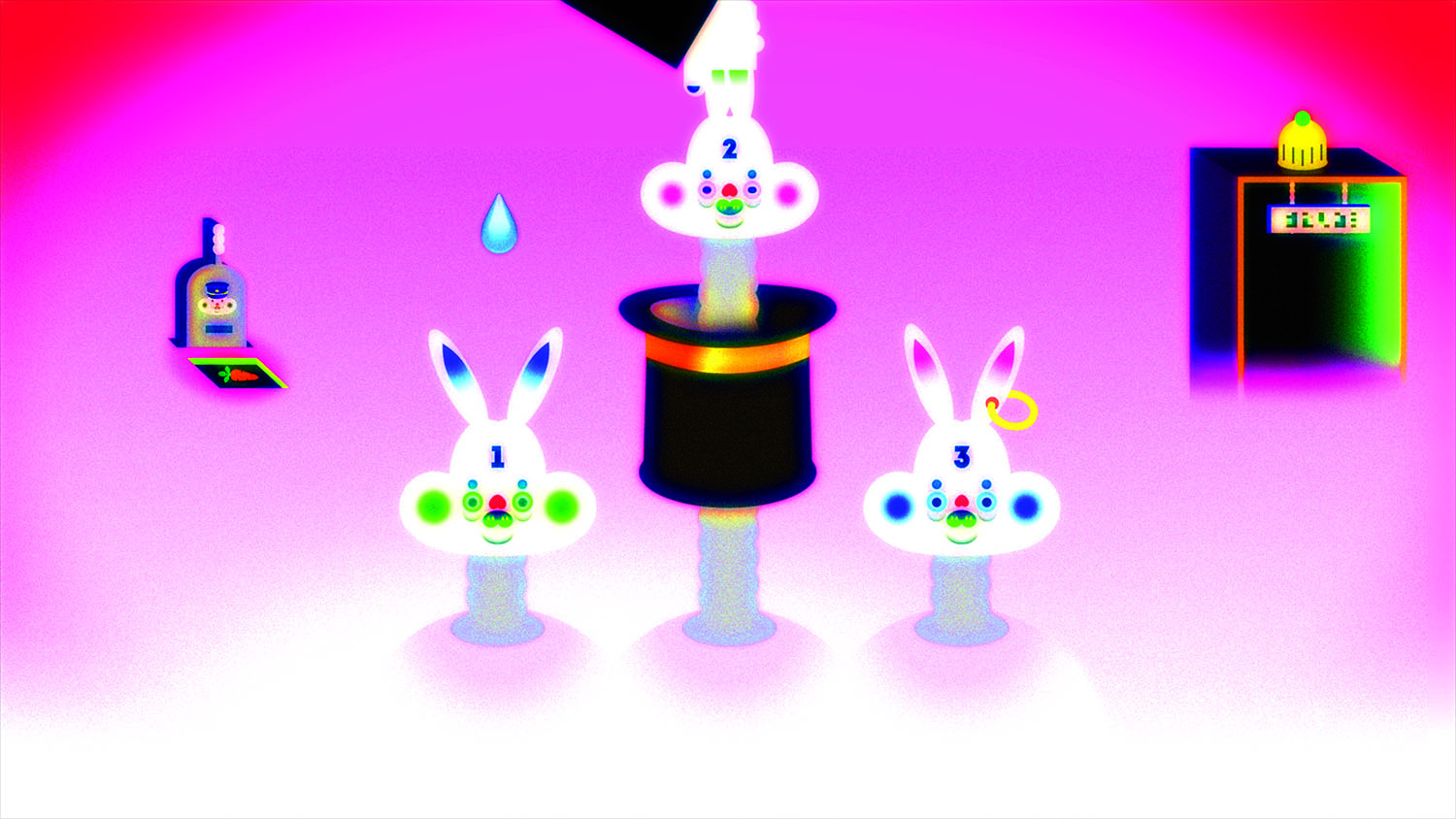

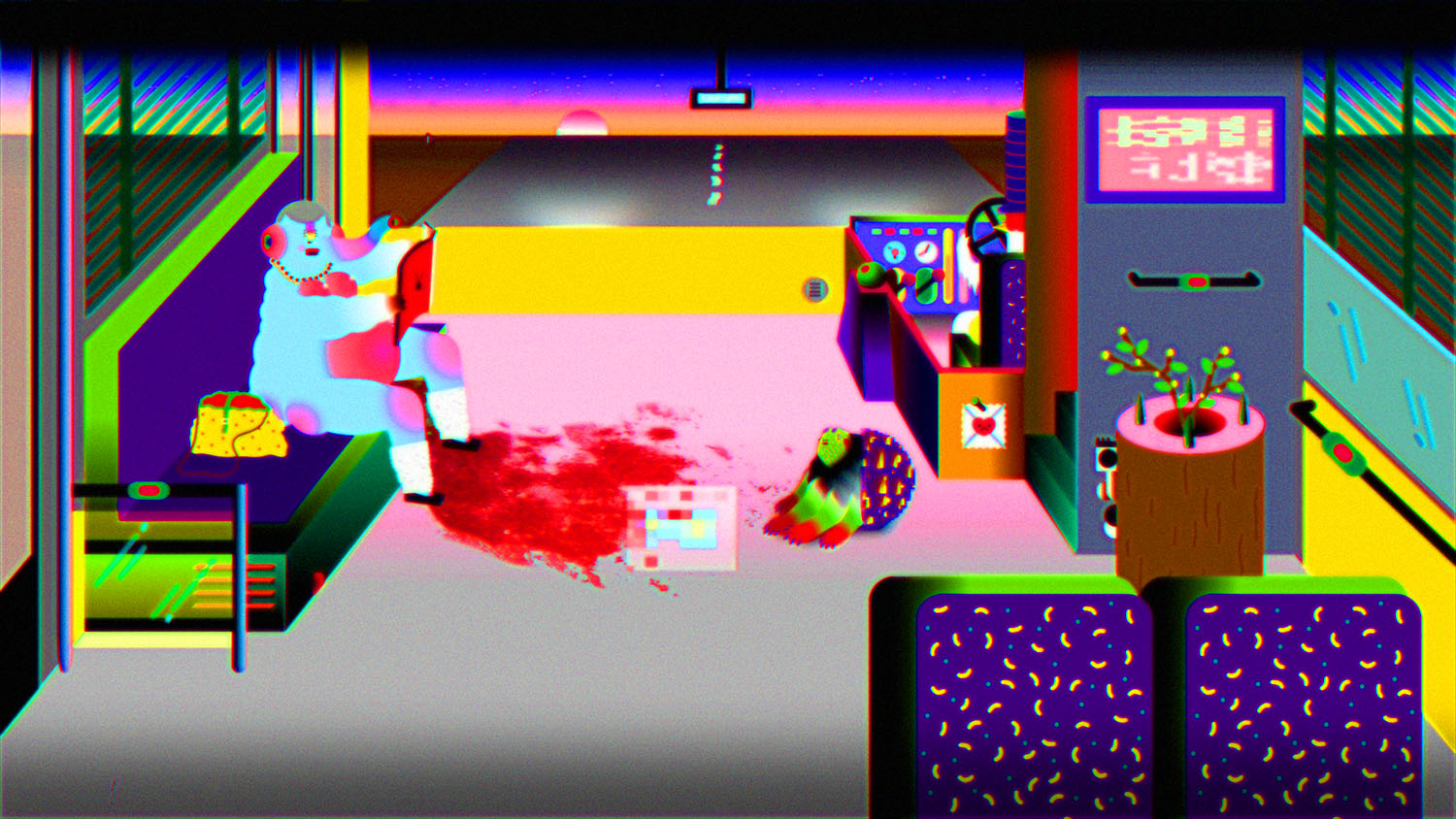

At the core of everything, however, are his contemporary fables. Wong’s solitary and introspective characters deal with social inhibitions, power struggles, and sexual fantasies. This latter facet is often presented in explicit terms, but it’s hardly stimulating, amusing, or shocking. There is a perpetual sense of melancholia lurking in the background that, coupled with the deadpan delivery of the voiceover, prevents his slapstick humor and deliberately childish approach to take over.

The most successful moment in “Heart Digger,” Wong’s maiden exhibition on UK soil, is undoubtedly Organic Smuggling Tunnel (Chunk 1) (2019). Borrowing from Robert Smithson’s idea of displacement as a form of representation, the piece exists both in the Camden Arts Centre garden and an off-site venue in Cork Street. Starting off with a romantic premise (the desire to dig a hole as a tribute to an imaginary lover), the tale continues with a shovel meeting a giraffe’s neck underground — a macabre discovery that leads to a plot related to a group of Hong Kong executives who create an escape route for themselves in case of trouble. The giraffe in question turns out to be an inflatable toy, but the smokescreen provided by this playful element is not thick enough to disguise the reference to Hong Kong’s current political predicament. Are the current protests a summer pastime, as cynics claim, or a real stand against the city’s government? Wong’s art doesn’t provide answers, but rather sound advice: this is indeed the time to start digging and look for the heart.