The eightieth iteration of the Whitney Biennial is subtitled “Quiet as It’s Kept,” an expression curator Adrienne Edwards remembers her grandmother saying to preface the airing of an open secret; the phrase similarly appealed to Toni Morrison for its “conspiratorial” undertones. That the exhibition begins with a dark antechamber leading to a series of black-box galleries, then, is apropos: whereas, in the arts, the term “black box” most often refers to experimental theater or a gallery darkened to exhibit video, in cybernetics and military discourse, a black box is a system that can only be known by its inputs and outputs. Quiet as it’s kept, the black box holds fast its secrets.

In most sprawling exhibitions, black-box galleries provide a reprieve from noisy, crowded exhibition spaces, allowing viewers to commune quietly in the dark with a moving image. For the Biennial, Edwards and co-curator David Breslin give the museum’s entire sixth floor the black-box treatment, granting even works in traditional media their own dark, semi-enclosed spaces. The black box loses its historical specificity: no longer a nod to 1960s experimental theater, nor to the moment in the 1990s when video invaded the museum’s white cube, the installation strategy instead becomes a curatorial metaphor for the Manichean splits governing American society.

Only one work, Alfredo Jaar’s 06.01.2020 18.39 (2022), receives a traditional cinematic black box: viewers can enter the work’s fully enclosed room at only designated times, and must watch the video from beginning to end. Here, the two histories of the black box — as site for immediacy in 1960s theater, and as chamber for multimedia immersion in the 1990s white cube — meet: while grainy black-and-white footage from the summer 2020 George Floyd uprisings is projected onto the wall, high-powered overhead fans whir on and whip the room into a frenzy, simulating helicopters flying dangerously low. The overall effect is that of a cheap thrill, an IMAX movie: Jaar’s installation provides all the pleasure of political action without the attendant dangers of having to leave the museum.

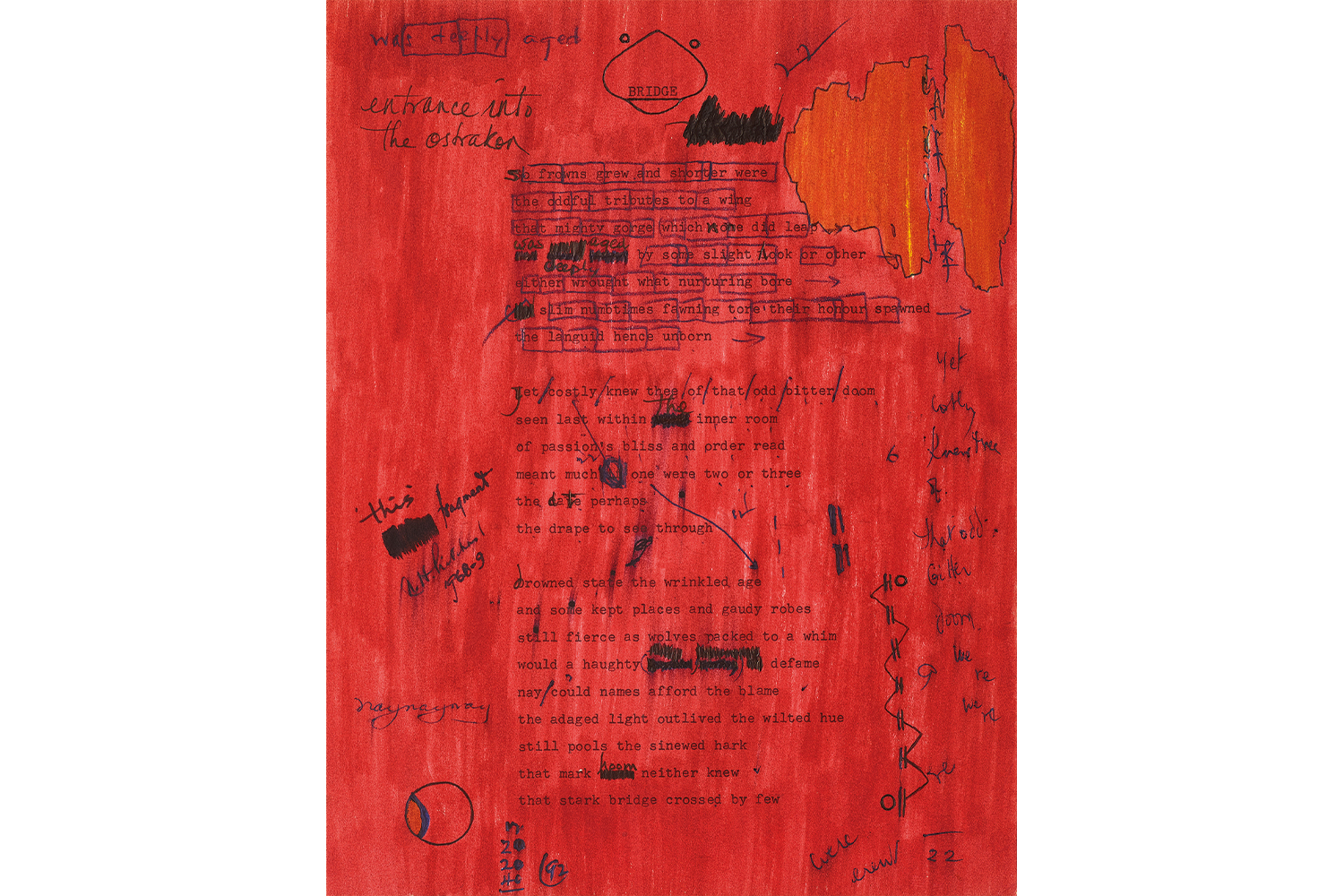

Less sensational but more affecting is Raven Chacon’s Silent Choir (2017), a sound installation that fills the exhibition’s antechamber, otherwise empty aside from a shrouded (and unidentified) work installed high on the wall and a glass vial containing Thomas Edison’s last breath, which fanboy Henry Ford collected on Edison’s deathbed. Like Jaar’s, Chacon’s installation reproduces a highly mediatized moment in recent US politics: the silent protest at Standing Rock in which women Water Protectors confronted pipeline security officers with only the sound of their breath. Unlike Jaar’s, Chacon’s work is haunting, especially coupled with the relic of Edison’s death. As one of the architects of a world in which massive energy expenditure continues to dispossess Indigenous peoples of their land, Edison’s last breath acts as a hopeful harbinger for the death of the fossil-fuel industry to which he and Ford helped give birth.

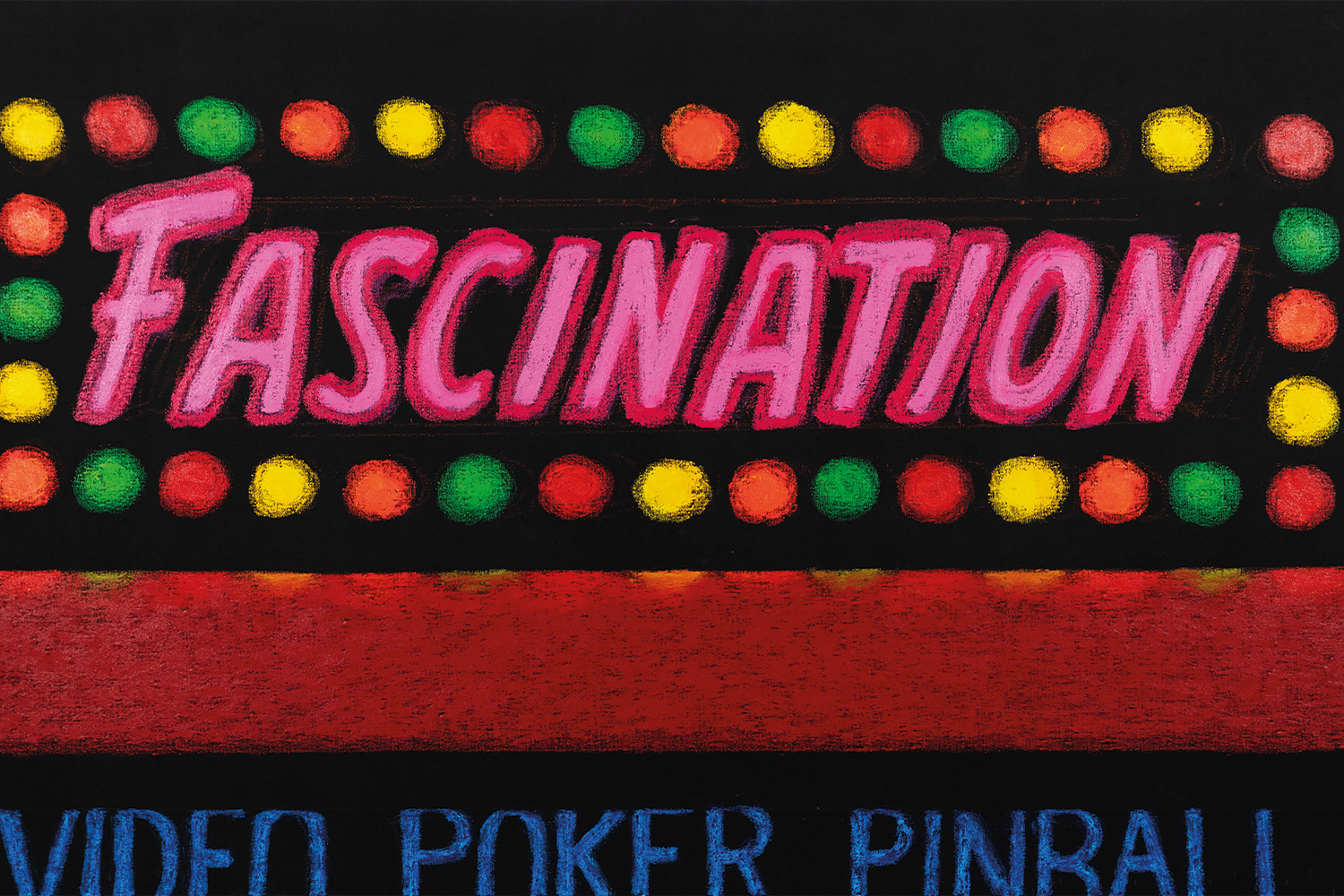

If, in this biennial, the black box loses its medium specificity, the white cube — which historically provided a supposedly neutral space in which objects can be encountered as if autonomous — is transformed on the museum’s bright, open fifth floor. Here, Emily Barker’s ghostly, translucent plastic kitchen, just oversize enough to be inaccessible, abuts Rose Salane’s minimalist piles of subway “slugs” (nonlegal tender used to trick MTA coin machines). Barker’s work makes visceral the frustrations of navigating the world in any body other than that of an athletic, 5’8″ + man; Salane’s indexes the moments of ingenuity and risk that accompany using casino chips or prayer tokens to navigate an increasingly expensive and heavily policed NYC public transportation system. Both point to the ways in which encounters within the white cube can never fully excise embodiment and context.

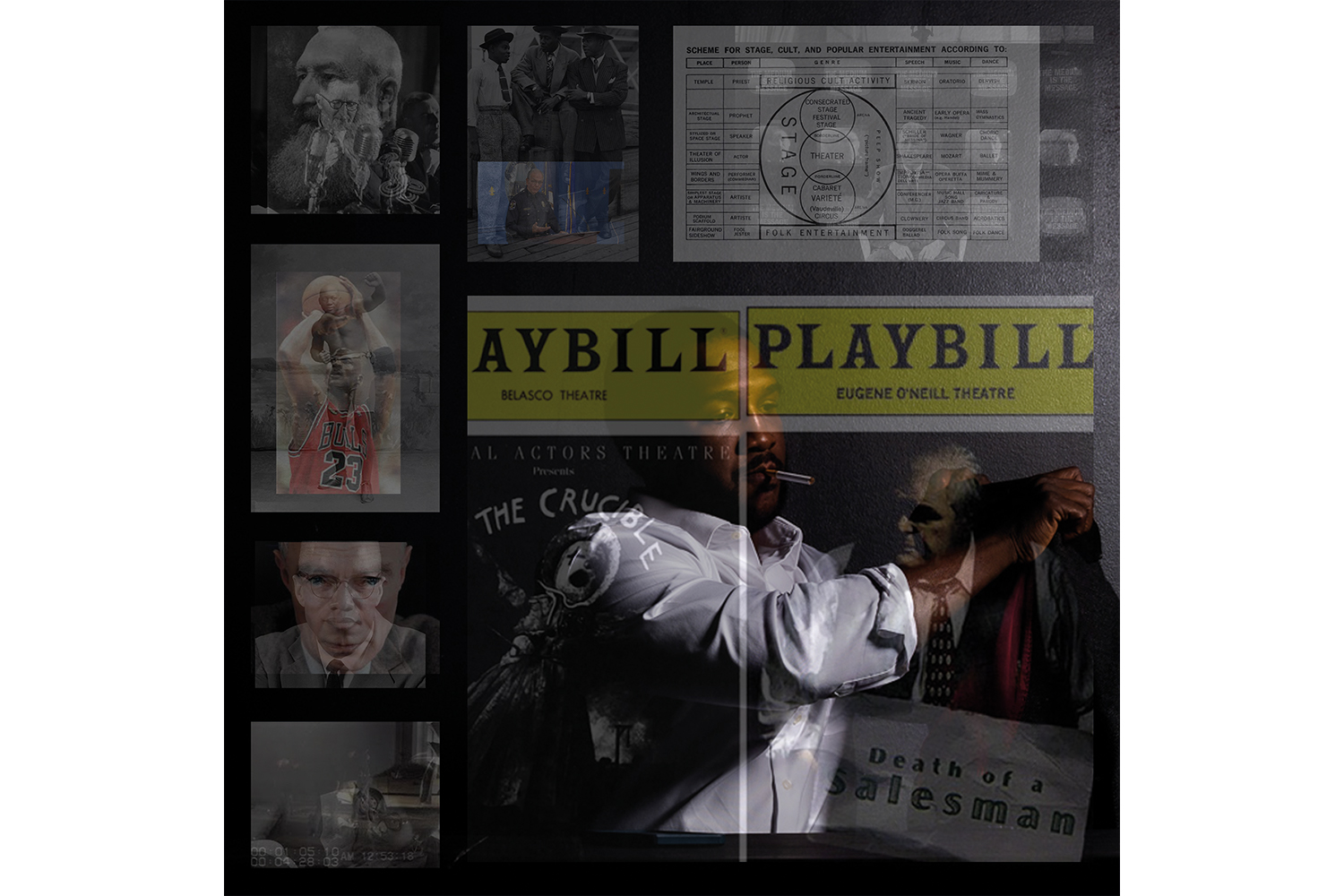

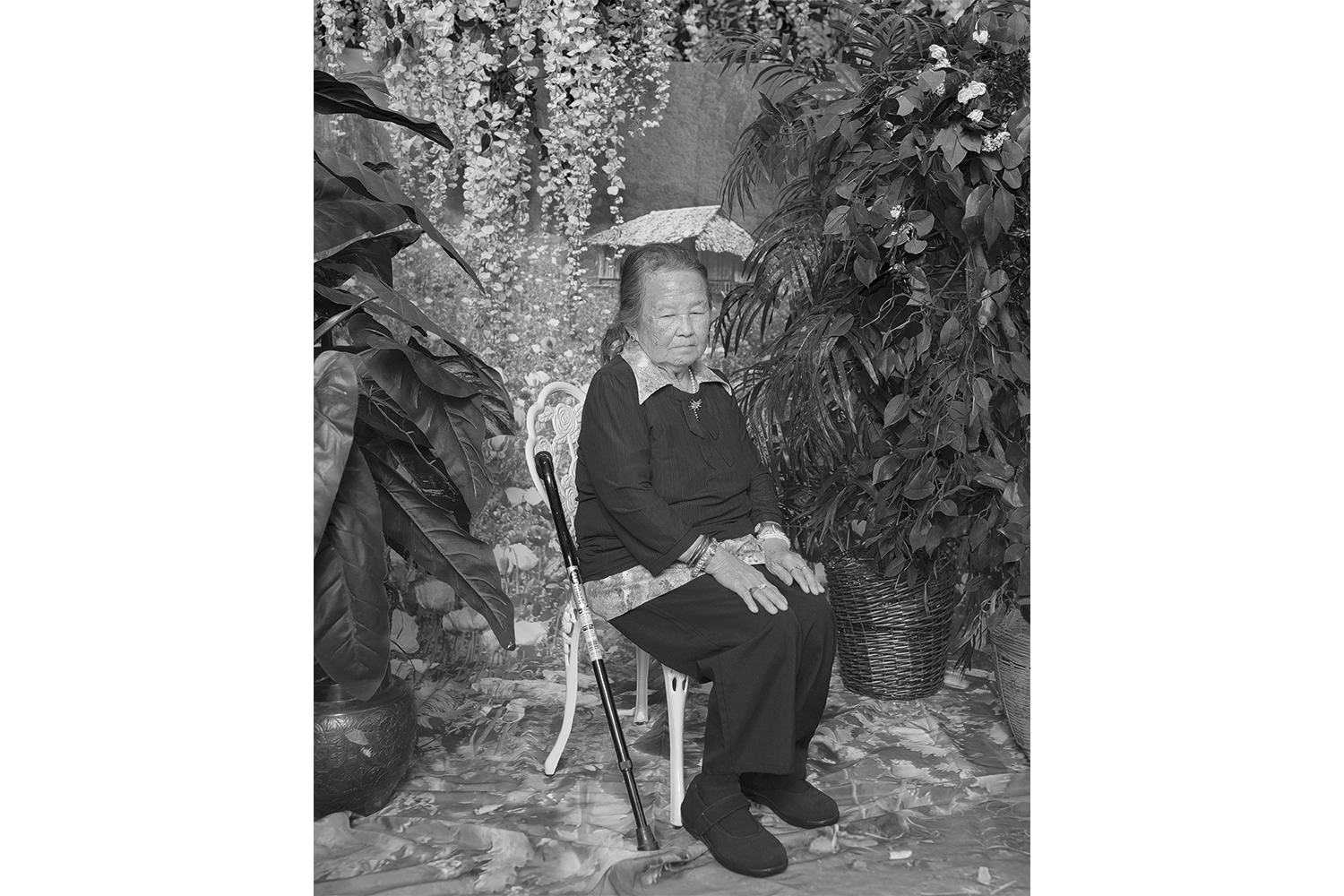

On the fifth floor, Salane and Barker emerge alongside biennial veterans, established names, and dead artists like Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, who was murdered in 1982 at the age of thirty-two. Contemporaneity is no longer a matter of being one of this year’s thirty under thirty; instead, the “now” appears as a nebulous zone of recurrences, repetitions, and hauntings. One work, though, holds fast to the white-cube model of history. Over the course of Alex Da Corte’s hourlong video ROY G BIV (2022), the artist gleefully dresses up as Marcel Duchamp, Rrose Sélavy, Jack Nicholson’s 1989 Joker, and one of the figures in Brancusi’s The Kiss (1916). In yet another art-historical nod — here to John Baldessari’s Six Colorful Inside Jobs (1977) — the artist’s brother Americo, a professional house painter, will, periodically throughout the exhibition, repaint the oversize cube onto which the video is projected.

By styling himself as inheritor of Duchamp, Brancusi, Baldessari, and others, Da Corte upholds a model of art history as a linear baton-pass of avant-garde gestures, each citing and transgressing the last. It almost goes without saying this is the same model that relegates artists like Cha to its dustbin by insisting that the contemporary always emerges from the same well-worn past. If Da Corte’s installation is one of the floor’s crowd-pleasers, though, it won’t only be because his is the only one to receive a seating area. The video’s production quality is high, its references satisfyingly identifiable, and its targets easy (in the final act, Da Corte-as- Brancusi-sculpture sprouts breasts, a pregnant belly, and a penis- turned-microphone for singing karaoke: eschewing any nuanced exploration of gender, Da Corte instrumentalizes transness to increase his video’s quotient of hot-button references).

Despite Da Corte’s facile transgressions, more than anything, this is a biennial determined to neither scandalize nor offend. The most overtly political works are by blue-chip artists, and go down comparatively easy against, for example, tear-gas manufacturing board members. But, while a museum can attempt to black box its funding sources, gallery attendants wearing union buttons are less easily kept from sight. Handing out masks at the museum’s entry, several workers told me that they found artworks that superficially engage labor politics, like Da Corte’s, hypocritical. The Whitney has been stalling contract negotiations and attempting to union bust since their staff voted to unionize last summer. Most of the workers that make the biennial possible earn less than $20 an hour and don’t have job security or adequate healthcare: that, though, the biennial holds “quiet as it’s kept.”