Cecilia Alemani has curated a posthuman biennial, or so the worldwide press reports. The New York curator used the term “posthuman” at the opening press conference, and also gave Rosi Braidotti — Italian pioneer of posthumanism — a special mention. While to art audiences, posthumanism might sound new and cutting edge, or even outright mysterious — the latest trend in a post-COVID world that’s lost faith in itself — the posthuman revolution has been causing a stir in academia for more than forty years, and its roots reach far deeper into 1960s Western philosophy as well as into early modern art.

While contemporary artists have seriously engaged with posthuman ideas for decades, it has been curators and art historians who have treated posthumanism with mistrust, a sign of an outdated anthropocentrism that still implicitly dominates the art world. Far from a fad, posthumanism is a vital construct we need to grasp right now, and urgently so, since the concept encompasses the causes of colossal issues like climate change as well as racism and sexism. Mounting evidence that climate change and the relentless planetary impoverishment caused by the sixth mass extinction are induced by human activities, is finally — but not quickly enough — proving that our misplaced sense of dominion over the planet has come at a dear cost. Posthumanism shows us how social justice and ecology are interdependent; trying to fix each separately will not work in the long run.

The first philosophical traces of the radical shifts that will thereafter become known as posthumanism became visible at the end of the nineteenth century in the work of Friedrich Nietzsche, only to resurface during the second half of the last century in the poststructural work of Michele Foucault, Judith Butler, Deleuze and Guattari, and Jacques Derrida. These philosophers were among the first to wrestle with the acknowledgment that the boundaries that define the human are a dangerous cultural construct. Their target was the blinkeredness of anthropocentrism — a byproduct of humanism: the Renaissance dogma that put humans on a pedestal and made us the measure of all things.

Humanism, the fifteenth-century revival of classical Greek culture, was in essence a survival mechanism. The Black Death, a global pandemic that between 1347 and 1351 killed some two hundred million people in Eurasia and North Africa, left humanity to grapple with a deep existentialist crisis. Why would God unleash such terrible punishment upon its finest creation? It’s in the aftermath of this tragedy that humanism emerged as a formidable antidote: a philosophical system of thought, bolstered by Christianity, that reaffirmed the importance of human intelligence and accomplishments above all other creatures. Humanity needed to find confidence in itself again, and, as the artistic production of the Renaissance amply demonstrates, humanism served us well for a few centuries, until it turned into outright arrogance.

In philosophy, the rise of posthumanism has coincided with the relentless deconstruction of the rhetoric and aesthetics of humanism that have perpetuated the privilege of the human over the nonhuman and the outlook of the white, male, cis-gendered individual over that of others. Black scholars like Frantz Fanon and Sylvia Wynter were among the first to openly denounce the racial bias of humanism that all along underpinned the exclusionist project of Western philosophy. They anticipated and broadened the interrogation of the very notion of “man” in Western thought, further enhancing the theoretical urgency of what will become known as posthumanism.

Throughout the last century, artists like the female Dada pioneer Hannah Höch have also been aware that “the human” as a concept was, since the dawn of colonialism, crafted out of the exclusion of BIPOC and other minorities who were typified as lesser humans: LGBTQA+, Jewish, Roma, differently abled, and the neurodiverse.

Starting with the early 1980s, the female protagonists of posthuman theory, Rosi Braidotti, Karen Barad, Donna Haraway, and N. Katherine Hayles, among others, anchored the contemporary conception of the field to a markedly feminist framework. Feminism, as Braidotti’s new book Posthuman Feminism argues, is “one of the precursors of the posthuman turn.” The posthuman cyborg, a figure central to the philosophical theorizations of Haraway as well as Braidotti, is more than a science-fiction character but is a manifestation of an evolutional process that supersedes the classical conception of the natural and that fluidly situates technology as the matrix of bodily and social reality. As an incarnated intersection of information technology and women’s liberation, the cyborg blurs the distinct categories and identities that underlie the historical oppression of animals, plants, humans, machines, and territories — the foundational knowledge of the Enlightenment.

Not many of us know it, but we are all cyborgs. As Alemani noted in the press conference, during the pandemic, as we experienced unprecedented isolation, human affect became one with digital technologies. Old relationships were kept alive, and new ones formed on computer and phone screens — multiple networks of collaborations, solidarity, and conspiracy unfurled across the underwater internet cables that ironically, or perhaps tragically, are laid upon the shipping routes of early colonialism.

Posthumanism is not an anti-human philosophical movement. It decenters Western classical conceptions of the human to bravely reveal and embrace the ethical contradictions that have led us to today’s man-made environmental crises. It proposes an invaluable opportunity to reenvision our past histories in the knowledge that the ones we inherited were deeply biased and inaccurate to start with.

But it would be incorrect to suggest that posthumanist thinking is the brainchild of philosophy alone. Throughout the last century, artists have also been at the forefront of the posthuman revolution. A sense of unease with the fictitious objectivity and strict hierarchies of classical art (the quintessential visual manifestation of humanism) already pervaded the diffractive gaze of Post-Impressionism. Cezanne’s multifocal perspective and the Cubist fragmentation of the picture plane that followed it, along with the appropriation of African art aesthetics, revealed the conceptual tyranny of central perspective: an artificially objective construct, and Eurocentric outlook, that encapsulates the supremacy of whiteness in art.

Dada readymades challenged the authorial supremacy of the artist and posed radical questions about the essence of art and the role of the art object, paving the way for live plants and animals to enter the exhibition space. A not-so-well-known installation of genetically modified delphiniums by Edward Steichen held at MoMA in 1936 heralded the beginning of what today we call Bio Art — a posthuman branch of contemporary art. The practices of artists like Suzanne Anker, Eduardo Kac, Anicka Yi, or Micha Cárdenas entail working with living organisms at the interface of cultural as well as biological ecologies to which we are linked.

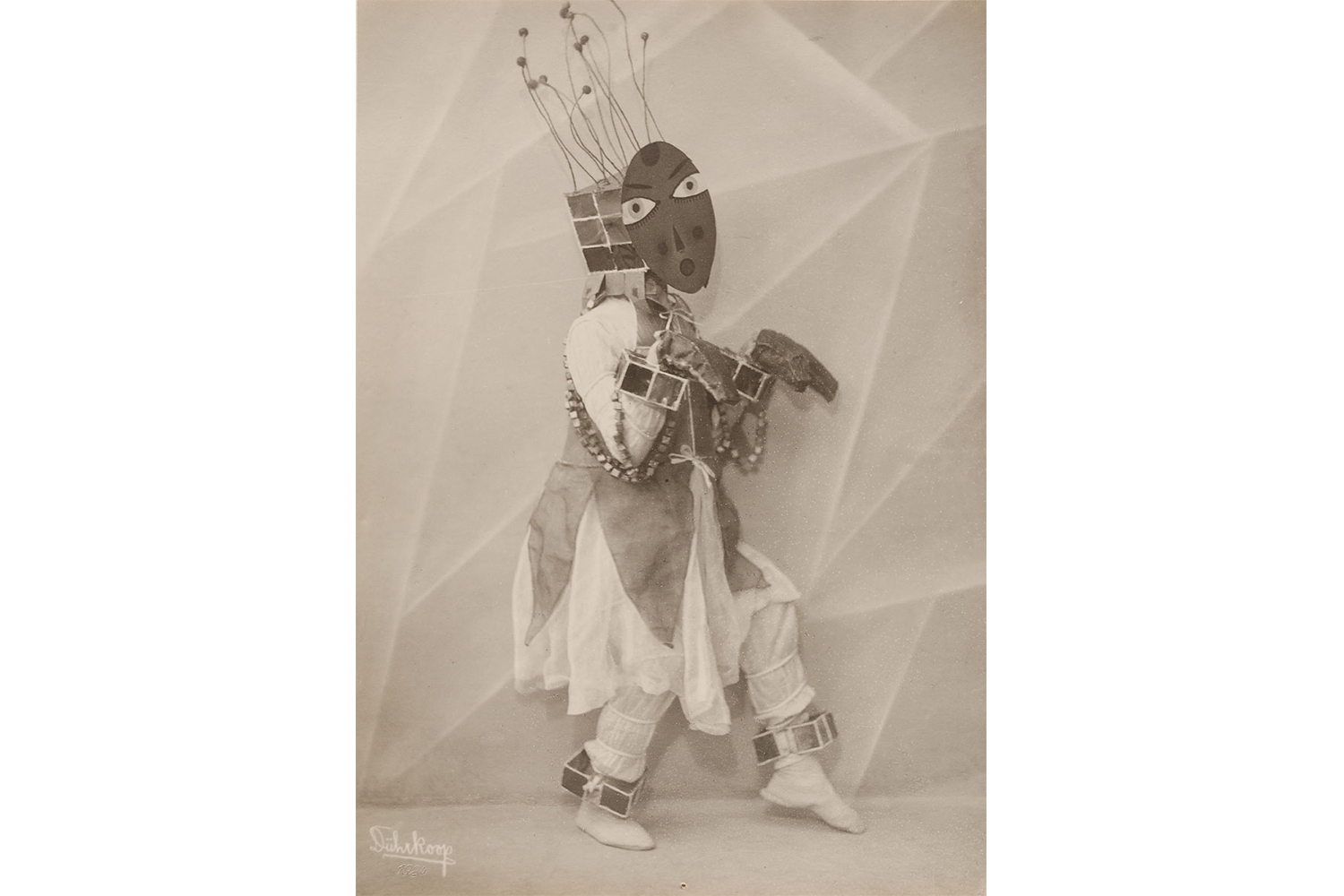

As the rise of capitalism, the mechanization of labor, and the growing hegemony of science in popular culture heralded an increasingly rationalized, utopianist, and sanitized modern world, the Surrealists sought to re-enchant reality through psychoanalysis, automatism, and chance. More than any other previous movement, Surrealism nurtured a pronounced posthumanist desire to upturn categories, follow the agency materialities, and relinquish authorial control. Artists like Wifredo Lam, Leonora Carrington, and Salvador Dalí turned to the unconscious, tapping into the creative potential of mystery and mythology to escape order and the restrictions of cultural norms. In this context, nature emerge in their work as an extension of our sensorial: the continuation of an inquiry that can be traced back to the biomorphic costumes (on show at the Biennale) of expressionist dancers Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt — opportunities to rethink ourselves at the edge of reason, as part of nonhuman networks.

Surrealist experimentalism also aimed to undo the entrapment of binary concepts as demonstrated in the brave and provocative explorations of gender alternatives by transgender Jewish artist Claude Cahun, Meret Oppenheim’s abject cup and saucer covered in fur, and Leonor Fini’s portrayals of strong and androgynous women.

But more than any other works made around the mid-twentieth century, Giacometti’s, haunting walking men sculptures capture the essence of an often-overlooked cultural breaking point: the end of humanism. Striding forward, going nowhere — the anti-heroism that characterizes these “human shadows” expressed another deep existentialist crisis induced by the incomprehensible brutality of War World II atrocities. Emerging from this traumatic aftermath was a new determination, driven by a sense of ineluctable responsibility, to critically address what it might mean to be human at a deeply tragic point in history. At stake was the far-fetched possibility of building a fairer future upon the rubble of a delipidated past. It was a futile pursuit. Posthumanism shows us how building upon the foundations of colonialism and capitalism will only further entrench us in inescapable, historical circularities.

By the end of the 1960s, the experimental irreverence of the Gutai group in Japan, Arte Povera in Italy, and the innovative approaches of artists like Yayoi Kusama, Joseph Beuys, Judy Chicago, Sun Ra, and Carolee Schneemann, to name only a few, had drastically decentered the human as implicit master of cultural discourses.

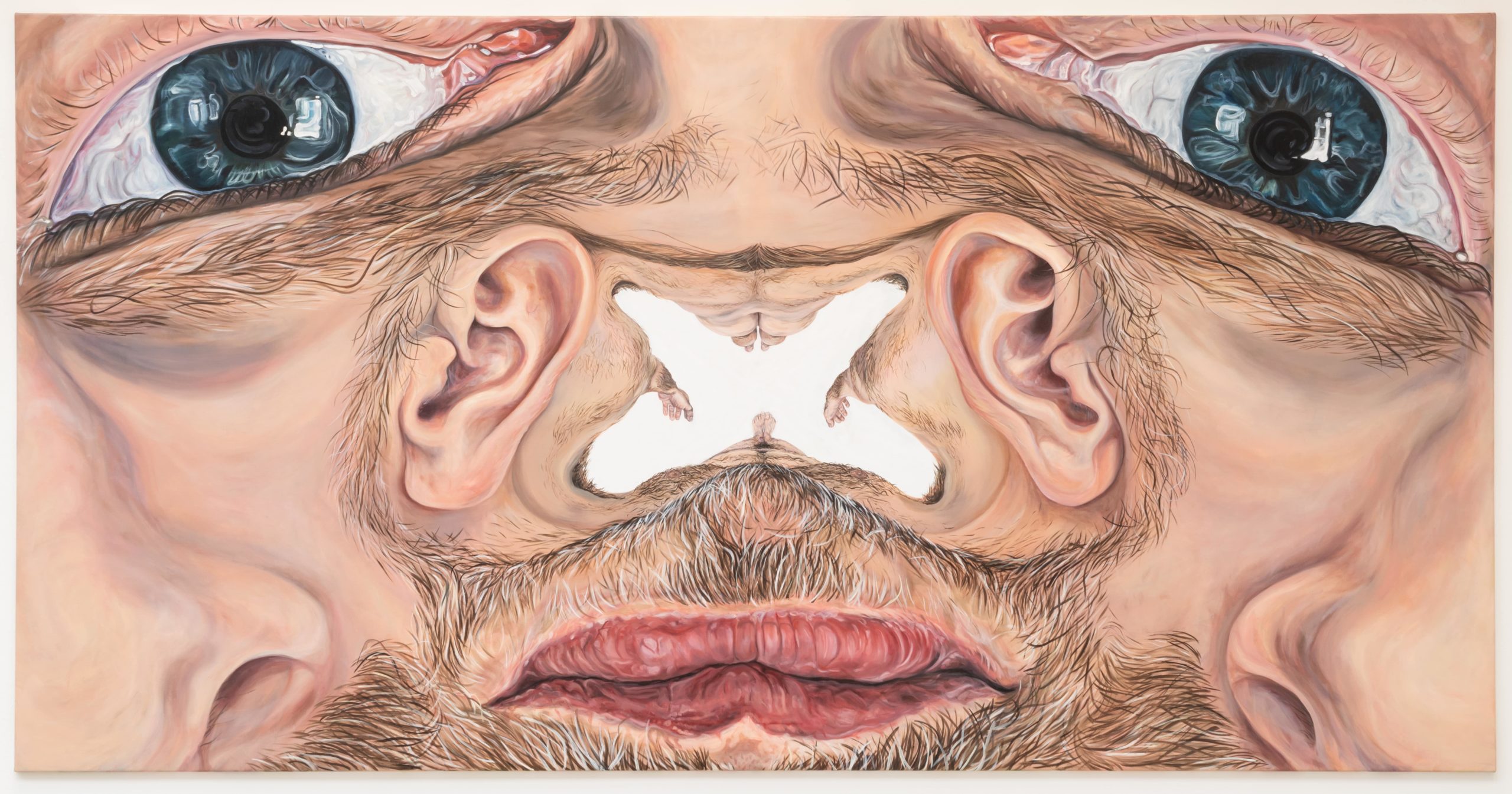

The breadth of identarian, aesthetic, and material diversity presented at Alemani’s Biennale is a timely and organic development of these genealogies. This is particularly visible across the three major thematic articulations that comprise “The Milk of Dreams”: the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses, the relationship between individuals and technology, and the connections between bodies and the Earth. The fictitious idea that the human body is a closed and finite entity is effectively brought into question in Andra Ursuta’s crystal sculptures and Jana Euler’s paintings. Ursuta fuses human anatomies and everyday objects, byproducts of late capitalism, of which we have become indissolubly a part — perpetrators, as well as victims. Euler’s paintings reconfigure the markers of identity beyond the bounds of human morphology into fragmented entities induced by cultural, social, and technological forces. Her work engaged with the biological and disciplinary fluidity that are central to posthuman conceptions.

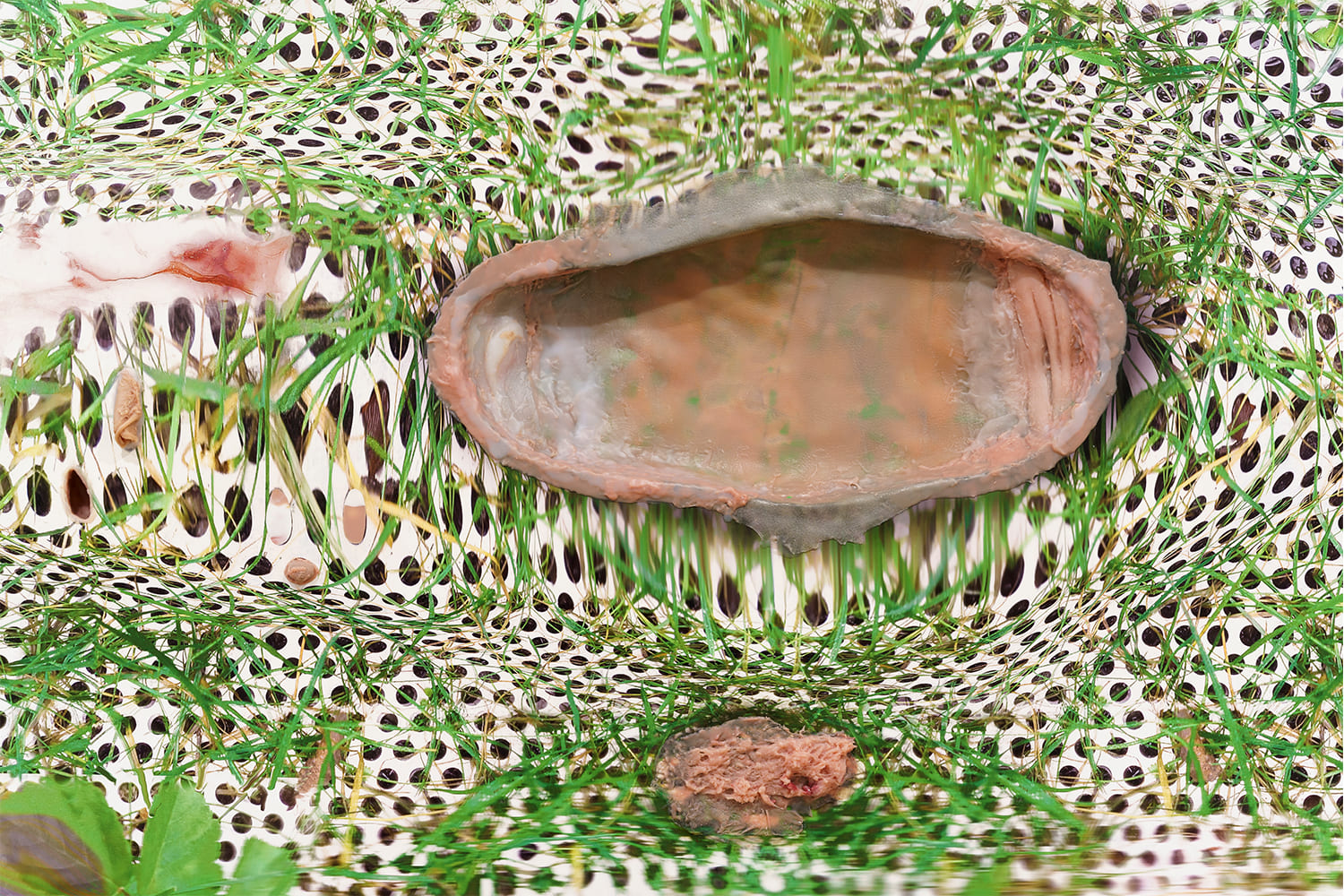

Felipe Baeza merges painting, collage, and printmaking to explore the resilient nature of the fugitive body: the physical transformation from human to vegetal is configured as a redemptive mythology of persecuted and marginalized peoples. Bathed in an otherworldly green light that flattens space and disorients, the faceless, spectral figures by multimedia artist Sandra Mujinga pose radical questions about the violence of Black representations in a surveillance society. Meanwhile the immersive installations of Precious Okoyomon and Delcy Morelos plunge the viewer into sensorial journeys of discovery that bypass linguistic structures, instead favoring the scents of soil, cassava flour, cacao powder, and spices: invitations to rediscover the agency of materials beyond the tradition of Western aesthetic and scientific conventions. It is no coincidence that Morelos’s maze should be influenced by Andean and Amazonian Amerindian cosmologies, while the biomorphic hanging bodies by Ruth Asawa employ a weaving technique the artist learned from Indigenous basket makers in Mexico. Similarly, Igshaan Adams’s tapestry-and-twisted-wire installation collapses notions of space and time and addresses contemporary contradictions through the Indigenous Northern Cape riel dancing style.

It is common to initially feel unsettled by posthuman propositions — they are radical. Posthumanism is about embracing uncertainty and mapping uncharted territory. But the uncertainty that posthumanism instils is productive and liberating. Ultimately, posthumanist frameworks allow us to understand that humans are part of complex, interdependent, and fluid networks that have often been concealed by the hubristic sense of protagonism we have shrouded ourselves in to deny our existential fragility. Posthumanism is an invitation to reconfigure our existence, redirect our attention, and reconnect with others (human, nonhuman, technology, and ecosystems), not in a romantic but in a responsible, engaged, respectful, and never-objectifying way.

Perhaps unaware of what posthumanism actually entails, some critics insist on reading Alemani’s Biennale as a fanciful representation of a threatening dystopia. Instead, this Biennale bravely shows us a truer world — the mostly messy, sometimes frightening, marvelously complex, and richly diverse evolutional becoming we are indissolubly enmeshed in. Is this a dystopia? No. It’s just the long-overdue demise of a patriarchal world order that, under the false pretense of purity, perfection, and progress, gave us colonialist atrocities, genocide, irreversible ecological damage, racism, sexism, and never-ending conflict.