Hans Ulrich Obrist: The interview happens now at the corner of rue Jacob and rue Bonaparte. Already this interview goes completely circular and reminds me of your favorite message from The Young Ones [British TV series, 1982-1984].

Trisha Donnelly: Oh yes. “Meanwhile, the next day.” It’s a break of narrative formula, usually for film, TV or radio. Something is happening in the plot and normally the device is to say, “and the next day” or “meanwhile in Paris” or “meanwhile in Los Angeles.” In The Young Ones, in between the change of a scene, all of a sudden it says, “meanwhile, the next day.” It reversed the function after that, but of course then you realize the next day is the projected idea of the next day.

HUO: Rirkrit Tiravanija would say “tomorrow is another fine day.” It’s a very Buddhist sentence.

TD: It’s true. But then you don’t have a past but you have a future. So “meanwhile, the next day” I think is a simple validation of the space and time continuum suggestion.

HUO: You said this is a totally historical and indestructible idea.

TD: I think that when you have a phrase that names the next day as being the past it is completely indestructible. Once you say that tomorrow is the past, it is indestructible. The duality of any day is that it is bookended by the ideas of the previous day and the day to come. In some ways it seems our memory is much simpler than we think, so we project memory into the future. We have a memory of the future…

HUO: Recently Stephanie Moisdon curated a show that included your first piece. Can you tell me about it?

TD: It was called She Said (1989). Funny. I was sixteen and came to understand the object nature of “ ”. If you have words and they are said, then they are said and they stay in the environment like a load of mass. She Said is about the first time I understood that; it was the same sensation as mass. So it’s the side of a chair and it just says “She Said” painted on it.

HUO: Could you talk about your drawings?

TD: I think that they relate to objects the way that you listen to the radio, if you have a radio on. I draw when the radio is on. When I’m drawing, I just wait a really long time because I have to do the right thing. So I don’t draw all day, but when I have the thing I am supposed to be drawing, I draw all day and all night.

HUO: It comes from an object or it comes from an idea?

TD: Both. Sometimes it comes from the sight of an object; sometimes sight is virtual. Some of the objects are sounds; some of the sounds are drawings, but I think that the drawings that I do are more of a physical realization of what I am thinking of than of myself (i.e., an action). Drawings can be a more intense version of the presence I think. They can act as actions. They are worse. More horrible. More distant.

HUO: We have [Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris] two drawings published in the catalogue I Still Believe in Miracles. Can you tell me about them?

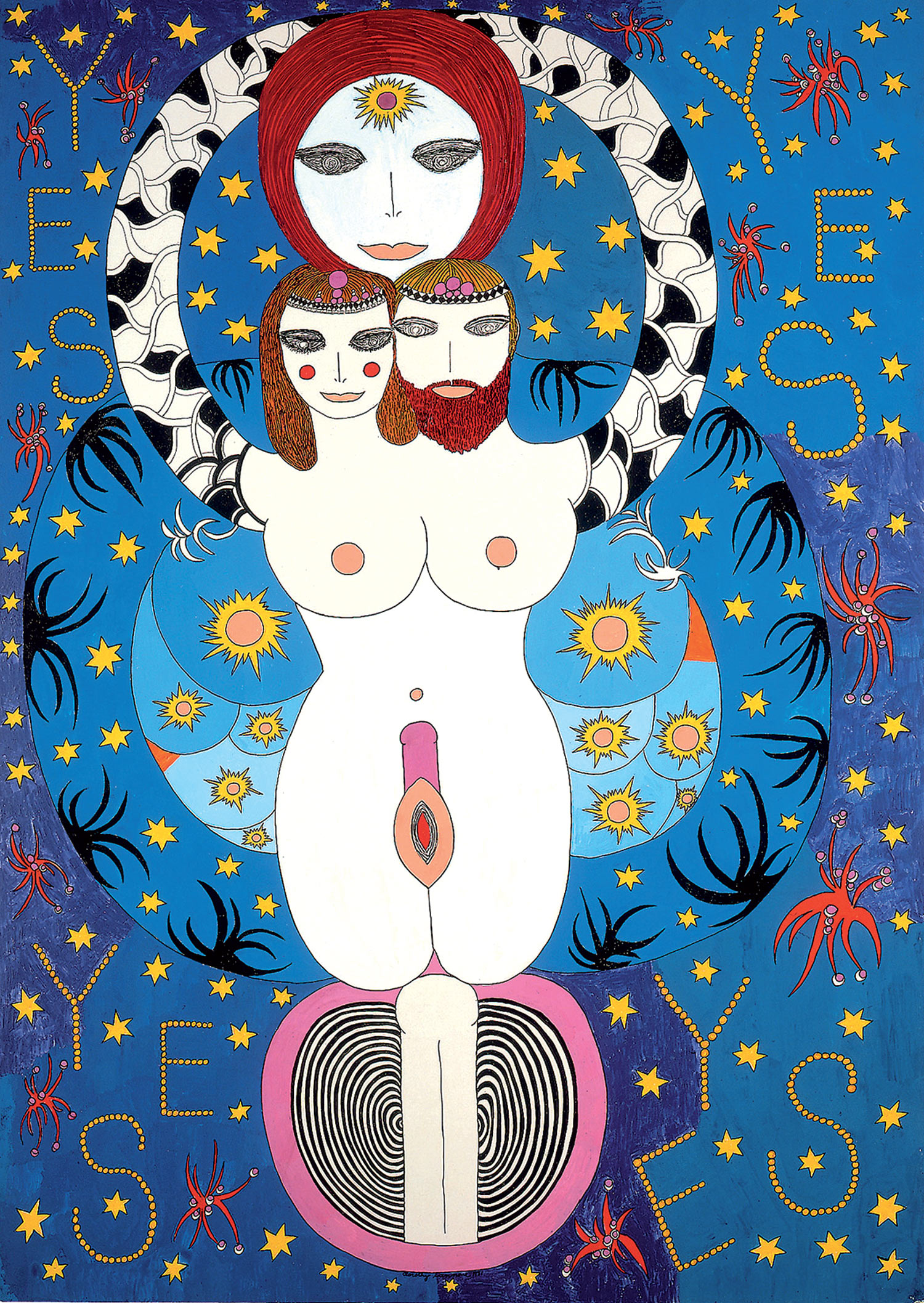

TD: Well, one is Untitled. This drawing is of an extinct object, which is this specific act of unlatching on a leg. It’s an action that is extinct because people don’t know how to put them on or take them off anymore because they are not worn. Every time somebody would ask at the place where it was shown, “What is that?” the person who works there has to show them: “it is…” So Untitled is that. And the other one is The Vortex (2001), which is the beginning of something I understood very simply with physical space. You know when some people see the color red they have a fit, which they think separates them from the normal world. It’s a physical response to the visual. So the vortex is something that I have understood as one of those thresholds.

HUO: Rupprecht Geiger, the more than ninety-year-old German painter, for many decades developed an almost obsessive attraction to the color red. There is a physical aspect to red.

TD: I think perhaps red is our most physically humanly understandable color because it’s the first time we see ourselves dying. Blood pouring out.

HUO: So The Vortex has to do with perception.

TD: It’s more than that, I think. It’s not even as much perception, but it’s imperceptible motion: you realize that you physically move through the viewable image. The corresponding piece is a demonstration — also called The Vortex (2003) — I did which consists of a Russian song where if you link the highest man’s voice and the lowest man’s voice you can build a vortex in your mind. When I play the song and I state the formula, each member of the audience builds a sculpture in their mind that is like a vortex. So you have hundreds of these built and rendered, point-placed never-ending vortexes in people’s minds. Hundreds of sculptures. I consider it more of a sculpture. A mass.

HUO: The drawing is a trigger for vortex. It is not an object in this regard.

TD: It’s not. But a vortex is never an object; it’s something else. We don’t have a word for this. It’s the same problem when you don’t have a word for “not performance.” It is not performance.

HUO: Cartier-Bresson told me the last time I interviewed him: “Photographs should be more seen in books than polluting too many walls.” The same thing is true for the way you use drawings and photographs; they are rare instances. It is against pollution.

TD: Yes. I think polluting something displays that you are sure of things and mortally terrified. Every time you make a piece of work you have to ask if it really needs to exist in the world and should you do the deed of adding more shit to the world. I write every day; that’s more where I do my everyday obsessive habit.

HUO: So, the writing, the texts are a daily practice for you.

TD: Yes, the texts. They also take a long time. Sometimes I begin a text one year and then I finish it in four years.

HUO: I am very interested in this link from art to literature and poetry because art has created all kinds of bridges in the recent years to music, to cinema, but the link to literature is too rare. Your own is a very rare instance of bringing back that link to poetry, and what is interesting is that poetry is maybe the only art form that has not been recuperated by the market.

TD: It never will be. The only time it had a possibility was in advertising, which has beautiful stuff sometimes. But poetry has regained its status in a way: as people believing that it has a compression that is important. It’s both horrible and perfect simultaneously.

HUO: And you are a native daughter of San Francisco, which is a city of poetry; I think of City Lights Bookstore and the whole beat generation. Have these people been important for you?

TD: No, actually, not at all. I was not so much a beat fan. Unless you could call Gertrude Stein a beat. But it’s a different temperament.

HUO: And who are your heroes in poetry?

TD: I love Ahkmatova, Marianne Moore, H.D., Michaux and I love Yeats because I have an obsession with the Irish disaster, the feelings of disaster. If a text’s category is somehow loosely dependent on structure then so many things can fall into and out of the form. I had a kind of dumb attraction to film moments in poetry. I grew up watching films that were already old. We weren’t allowed to watch TV so we watched John Wayne’s films, Gary Cooper’s films, classic westerns, so I think there would be these epic statements that act as catalysts more than like a constructed poem. John Wayne would walk into a space and say something and then the entire film would shift. The film in this type of action set up is literally built for and around his lines. Set-up lines, to wind its way around the text. The mass of the word. It is kind of like this basic masculinity, mutuality and intensity that are like an explosive statement, the low-grade hesitation and the verbal release. Some films have shorter leashes for this type of thing and make a faster dialogue. Snap you back in quicker. So, if you could build poetry that had a function to move a plot or a story, that was what I found really incredible. But you know I think I was looking for it. I needed to translate it into that structure. It’s text with camera movement built in, understood as part of the formula, like writing with the correct sense of punctuation.

HUO: You film when you travel. You were filming here in Paris too. What about your filmmaking? Is it a daily practice for you?

TD: It’s a daily accidental thing. The camera is palm sized. I never think about it.

HUO: Can you tell me about your bigger photographs?

TD: Some big, some small. The big ones are more like architecture. So polluting with columns. We should have a problem with photography. That’s all I know.