Maurizio Cattelan: How old are you?

Dorothy Iannone: Seventy-two.

MC: What was the first thing you did that you consider art?

DI: Well, good art, and speaking in retrospect, then probably my abstract expressionist paintings from the beginning of the sixties.

MC: When did you realize you were an artist?

DI: I don’t remember any particular sudden awakening to that fact. When I began painting and drawing in 1959, something clicked. I felt at home and going on was never in doubt.

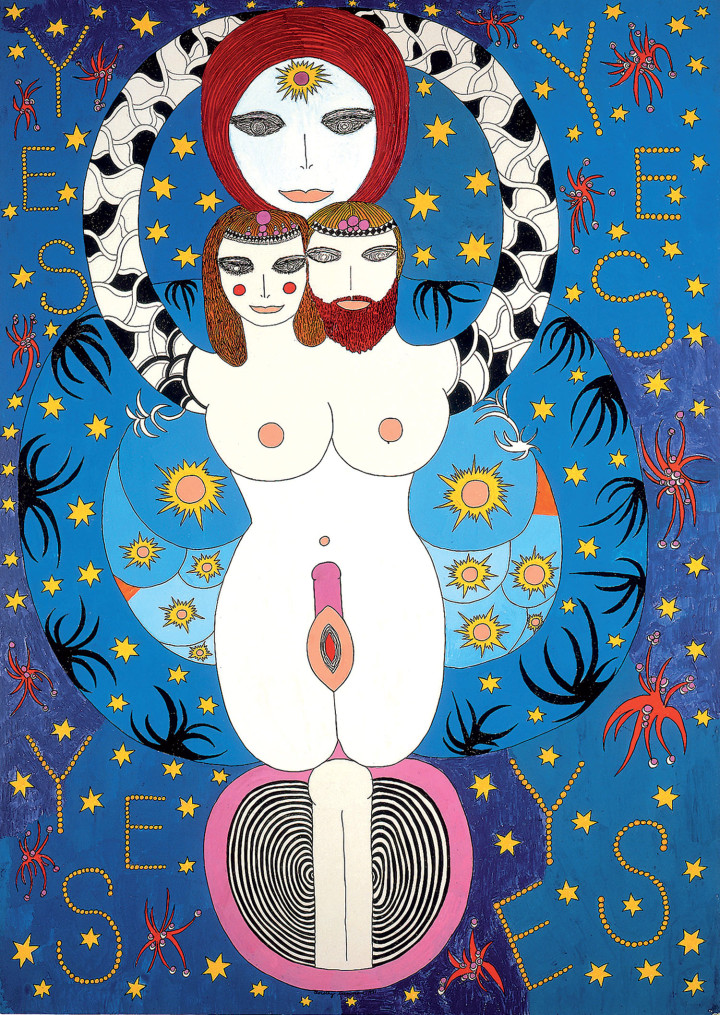

MC: When did sex first enter your work?

DI: Gradually my abstract expressionist paintings included figurative elements. And from the first moment, around 1963, whenever I painted a man and a women their sexual organs were not only present but sometimes prominent. This couple most likely represented me and my husband. In 1966, I made a few hundred wooden cutouts of everyone in the world I could think of, real people, mythological people, invented people, and I always included their sexual organs even if they were fully dressed. In a few cases, I copied couples actually making love from Greek vases and Indian temples. So, you could say that through the precedent of classical art, sex entered my work.

MC: How was your first time?

DI: I think it was sweet. We were teenagers in love. I enjoyed having sex with my boyfriend. I gave as much of myself as was available to me then. But I held back much more, though I was unaware of that. Every Saturday afternoon I had to go to confession in order to take communion at Sunday morning mass. I always went to Father Donnelly because he was so lenient with us sinners.

MC: When did you first meet Dieter Roth? How important was his presence in your work?

DI: We met in 1967, when I sailed to Iceland on a freighter with my husband and our friend, Emmett Williams. Dieter was waiting for us at the pier. From the moment I met him until the time I left him, my relationship with Dieter was the inspiration of my art. No longer did I paint other people. The two of us became the stars of my work, and instead of using lines from poems which I loved in my paintings, now I recorded what we had said to each other, or I wrote my own texts. No longer was I obsessed with the high love of Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra, now I had found my own, and in the course of recording it — not only the ecstasy but the domestic scene too, and the difficulties — my work went into many new directions and took on many new forms. Because I was so much in love with him, Dieter was my muse, and though he had probably near foreseen this role in his life, I think he enjoyed it very much. After our separation in 1974, Dieter appears only now and again in my work, but he never leaves it completely. Sometimes circumstances call for a piece starring Dieter.

MC: How would you describe your work?

DI: That’s a very difficult question! A description of me and a description of my work wouldn’t be that different. A longing for ecstatic unity. A journey towards unconditional love. A celebration and a stubborn insistence on the goodness of Eros, yes, but also works with or about my friends, other artist friends, my mother, the children of my friends, women’s condition, men’s condition. Giving everything I can — singing, making films and spontaneous, never documented performances, painting, drawing, making games, furniture and books, writing songs and texts. Creating a story through words, colors, sounds, images, and a propensity for veracity.

MC: When did you make your book about everyone you had slept with?

DI: In the early months of our relationship, Dieter asked me with how many men I had slept in my life. It had been eight years since my husband had asked me that same question and, in between, I had not slept with any other men. So, I had to think about it. I made a drawing of the first scene which came into my mind when I thought of the person. I also made a chart with the first name of my partner, or just his initials if he were well-known, or some other identifying characteristic if I couldn’t remember his name, my age, and whether it was just heavy petting or if we had gone all the way.

In 1967, I don’t think women generally admitted to having slept with more than one or two or, at most, three guys. So now, in answer to his question, I presented Dieter with a manuscript of thirty black and white drawings. It carried the rather formidable title Lists (IV): A More Detailed Than Requested Reconstruction – from The Book of D & D. I intended to make a drawing of Dieter and myself for the cover of the book. The night before I started working on it, I had a dream that one of us was riding an elephant and the other a whale. When I woke up, I couldn’t remember who was riding which, but because of the anatomy of an elephant, I decided Dieter should ride the elephant, and I would ride the whale. About five years ago, Norman Mailer, an old friend, visited me in Berlin. We talked about the days we had known each other in Provincetown when I was still together with my husband, and he mentioned that a few of his friends had been in love with me then — “You were so virginal looking,” he added. I was really surprised by this description. I showed him Lists (IV). “Look — I protested — I had made love with thirty guys.” “Doesn’t matter,” he said. When he saw a painting I had done of my mother and myself as a little girl, with a text telling how, one day while nursing me, the Virgin Mary had appeared before my mother in a vision, how she smiled and nodded her head, and raising her right hand, she blessed us, and disappeared, Norman said, “Ah, that explains it.” Lists (IV), by the way, would have absolutely killed my mother had she ever seen it. Fortunately, the very limited circulation of early artists’ books (and, moreover, one published on the other side of the Atlantic) spared her (and me) this heartbreak.

MC: You have met so many incredible people and have been on the scene for so long, have you ever had the clear feeling you were making history or at least you were witnessing history in the making?

DI: No, never. When, for instance in 1959, the U.S. Customs seized some books from my suitcase which I had bought in Paris — among them the Marquis de Sade and Restif de la Bretonne — it never occurred to me that through my efforts to regain my books — which would eventually result in a change in U.S. law regarding the importation of Henry Miller’s banned books — I was going to make history. These books were returned to me on the basis of my post-graduate English Literature studies. But the next time I went abroad, I wrote the government before my return and told them which books I was bringing in and asked if I could be permitted to keep them, but this time, I specified I wanted them for my own pleasure. As it happened, that year I had bought some books of Henry Miller. If my petition succeeded, then anyone could bring Miller’s books through customs and not just people with special qualifications. The government refused and my books were confiscated. The New York Civil Liberties Union was delighted to hear that I had brought back Henry Miller, because they were prepared to pursue a long defense of one of America’s most important writers. And so, in 1961, represented by the NYCLU, I sued the Collector of Customs for the return of “Tropic of Cancer.” After the preliminary hearing, the government threw in the towel and my books were returned. Our success effectively removed censorship of every book by Henry Miller and was a great setback to censorship in general.

Some months later, Grove Press gave a party for Henry Miller and I was invited. When I arrived, they led me to him and said, “Here is the women who brought suit against the government on your behalf.” Smiling, Henry Miller shook my hand and amusingly exclaimed, “What courage!” Later, after the long dinner, as we shook hands again and parted forever, Henry Miller said, “You will go far.” I was twenty-eight years old and that made me very, very happy.

Maybe you could say that my book The Story of Bern which Dieter and I published in 1970 was a new kind of art history. It tells the story in words and drawings of the “Friends Exhibition,” at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1969, which at the time was directed by Harald Szeemann. Four Swiss artist friends, Daniel Spoerri, André Thomkins, Karl Gerstner and Dieter Roth, happened to all be living in Düsseldorf. They decided that each would invite as many of their friends as they liked, to exhibit with them. André invited thirty, Daniel six or so, and Karl, nine. Dieter invited only two, Emmett Williams and me because, he said, he wanted to show the intense relationship between us and him. From me, Dieter requested the (Ta)rot Pack, a set of twenty seven cards depicting scenes from Dieter’s life, as well as my Dialogues, a series of original books, in which I recorded, with drawings and words, scenes from our life, and Lists (IV).

Early on, there was concern among some of the artists that my work would cause trouble. The day before the opening, Harald and Karl put some brown tape over the genitals. This didn’t hurt the work physically because Dieter had hung everything in plastic containers. But after a discussion at dinner that evening, it was decided to remove the tape and show the work uncensored. However, the next morning, when the head of the board of directors saw my work, he declared most of it unsuitable. And so, Harald had to remove some of the works. As a protest against the censorship of my work, the day after the opening, Dieter removed all of his work from the show because, he said, his part of the exhibition no longer made sense.

John Giorno once wove my life into the history of poetry. He wrote Rose, one of his ‘found poems,’ I think they are called, using, among other materials, a letter I had written my husband. This poem was published in the Paris Review, in 1968. Shortly after I had left my husband to be with Dieter, I received a letter from him asking if there had been other men in my life during our seven-year marriage. He particularly named two of our friends with whom I often lunched alone in New York. In response to his concern, I wrote him this letter: “No, James, I never deceived you with anyone. I was completely faithful and I didn’t sleep with Dieter until I had left you and returned to Iceland. Emmett or Maurice would probably have liked to sleep with me, but they never even alluded to it. […] I don’t know how to make it stronger. You were right to be confident. You knew me well enough!”

When my husband showed our mutual friend, John, this letter, John asked if he could borrow it. In his poem Rose, John interspersed lines from my letter with excerpts from, among other things, personals columns advertising for sexual partners, articles about bird flu, about prostitutes and descriptions of fashion. My entire letter is embedded in Rose. When Emmett showed me this issue of The Paris Review, I was definitely not pleased. But when John visited me in Berlin twenty years later, it was no longer necessary to mention Rose. And now, I must say, it even pleases me to have provided the poetry for Rose.

MC: Would you say you have been part of any sexual or artistic revolution?

DI: To assess whether, for instance, my large hand-painted video-box sculpture, I Was Thinking of You, which I made in 1975 and which was exhibited in, among other places, the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, where I incorporated into the painting of a man and a woman making love a video of my face showing the stages of sexual arousal culminating in an orgasm, contributed to any sexual or artistic revolution, isn’t really my line. I wanted, among other things, to give a glimpse of, let’s call it, the soul which, at the moment of orgasm, passes fleetingly over the face. I made the video completely alone. It was self-stimulation of course, but in a way that’s irrelevant because, as the title says, “I was thinking of you” and masturbation is the only way it could have been done and remained art. At one point, just for fun, instead of showing only my seductive side, I made some of the funniest faces I could imagine. I don’t think I ever gave more of myself in a work. “The only gift is a portion of thyself,” Emerson says. I am always embarrassed when I see this film, even if no one is with me. I wonder how I could have made it but I’m so glad I did.

I love something Jan Voss, a friend of almost forty years, recently wrote about me on this subject for his website: “Dorothy has been for all the time I’ve known her an incarnation of all revolutionaries. She determined herself which hierarchy she would acknowledge and which to laugh away.”

MC: What are you looking for in your work?

DI: My work helps me in different ways, but essentially I do it because I like doing it. I like communicating my being. I never know at the beginning what a work will look like at the end. The moment something is finished, I experience a feeling of satisfaction, but this passes very quickly. The journey is all. For the last decade or so, I have begun hoping that what I do not only is good for me, but that others benefit from it as well.