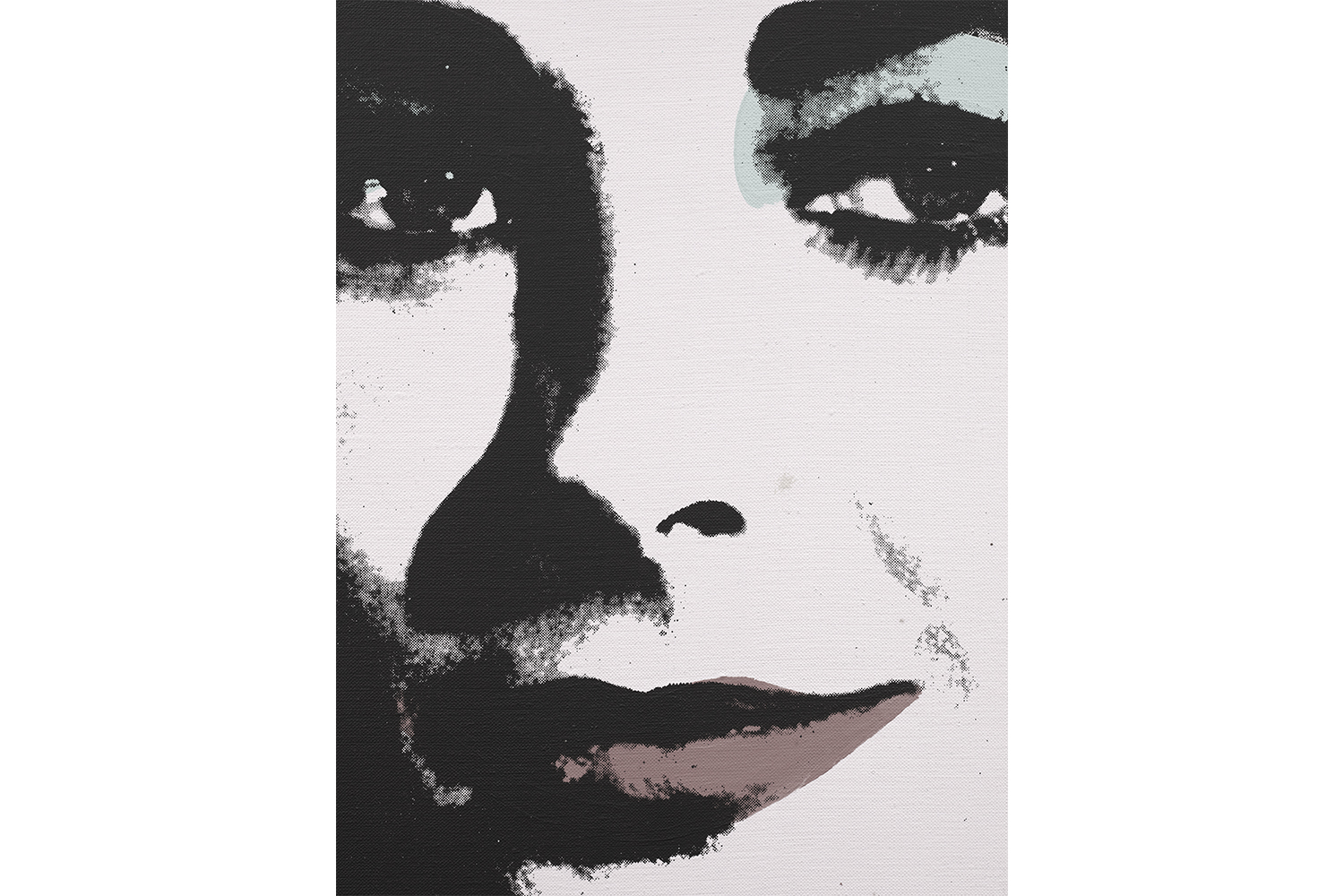

I do not know that Roe Ethridge’s work is ironic, because I don’t know that I am. This is not to say that I am Ethridge’s work, but if it is indeed some kind of comment on the culture, as I am told it is, I am a part of that culture and therefore have some say in the application of irony. Irony is calling yourself a Rock Chick when you are really a Square and you know it. Irony is not re-photographing Warhol, as Ethridge does in Warhol (Liz) (2011) or as Catherine Opie does in the series “700 Nimes Road.” Nor is re-photographing or photographing the mundane necessarily witty or droll, for those forms of humor carry with them a classist element, or at least a cattiness. I aspire to be a bitch and a Rock Chick, but I don’t think Ethridge does, and that’s OK. In any case, where is the cattiness in pictures of dead women made by dead men, carefree children, sublime settings, your own self? Only in a refusal to identify with such phenomena and to feel the emotions, both unbearable and pleasurable, that they engender. I maintain that neither Warhol nor Ethridge are apathetic, because I am not apathetic, and they are not glib, because I am not glib, and if we, or you, choose to be, then so be it.

When you get to wasps atop Chanel No. 5 bottles and pissing pigs though, maybe you have to find an art-historical reference to deal with the perceived or required lack of sincerity. Paul Outerbridge, like Ethridge, got his start in commercial photography, and he died of lung cancer and of printing in both color and teeth-white indiscriminately. I see that a comparison to David Lynch has been made a number of times in terms of some sort of violence lurking in a Norman Rockwell-esque interior, as with Father and Son in Kitchen (1941), in which two men chuckle at the expense of a note from the Woman of the House that reads “Gone to Bed, Prowlers Welcome. Mother.” There is a joke, and we believe we are in on it, as is often assumed of Ethridge’s work. Donuts and prowling and queer undertones and the occasional wink — Lynchian to be sure. It has to be said though that how we consider the surreal or sinister everyday often relies forcefully on the camera as a mediator, or as a denuding tool that sheds light on what “prowlers” might actually do when women are away. Prowlers might fuck each other and then kill each other, or they might do the same to women, or they might just get wasted together and go to the strip club and not kill anybody, or they might cross the storied red curtain into the Black Lodge and never be seen again, or they might help an old lady cross the street. A camera can tell us those things, but we cannot say that an arrangement of domestic objects or bodies is rendered spooky or otherworldly simply by having-been-photographed and subject to the formal characteristics thereof (cropping, doubling, lighting), for that implies that the surreality of Art is more potent than the surreality of experience, or that we require Art to access that surreality of experience.

Norman Rockwell also died of a smoking-related disease (emphysema). According to the Norman Rockwell Museum, “Rockwell made sure to have his pipe in hand whenever he was photographed for publicity.” At the same time, Rockwell also executed a mise en abyme painting in which a figure within a painting turns up his nose comically at a cigar left on the mantelpiece beneath him. It is titled No Smoking (1944). There is also an intriguing self-portrait of Rockwell smoking a pipe, but his face is obscured. Before I get too obvious here, I’ll just say that to be a smoker is to live with constant shame, and that shame is an arrangement of things and emotions. And I think that shame is something that is intuited rather than unearthed. It is something that does not always need the mediation of Art in order to be felt or shared. It is there with every pornographic image hidden under the bed, and it is there with every relationship that fails and every kiss or dick that is refused or refuses. It is there with every Hollywood star who dies and is memorialized unflatteringly and then re-memorialized again and again.

As we learn in an interview between Tim Griffin and Ethridge in BOMB Magazine, Ethridge’s iconic Thanksgiving 1984 (2009) is a reenactment of shame: “In 1984 my aunt, uncle, and cousins came to Atlanta for Thanksgiving. I was fifteen, and they brought my twenty-year-old cousin, whom I suddenly developed a crush on. That’s the picture that I need to recreate, I thought, that forbidden desire. It was embarrassing.” I want to know, since my cousins are quite homely, what that is like. And Ethridge tells us what that is like, not in a self-conscious display of artifice or an unexpected juxtaposition that somehow reveals something heretofore unseen to us, but in his car that he accidentally let slide into a canal while he was preoccupied taking photographs in his mother’s hometown of Belle Glade, Florida. And this is the story that he chooses to recount at the end of his book Sacrifice Your Body. If that’s not a metaphor, nothing is, as is the bank teller with a small sign that could be in a Norman Fucking Rockwell painting: “I Took A Pain Pill — Why Are You Still Here?”

But opioids are not really metaphors, and neither are unattractive people who, fishlike and like myself, still aspire to wear Chanel, and neither is Belle Glade’s nickname “Muck City” or the fact that the city appeared in a 1960 Edward R. Murrow documentary called Harvest of Shame that aired on Thanksgiving Day, and neither is a photograph. And neither is the feeling that one’s professional life and one’s youth are dissonant and wanting to see if there is any way that they could be continuous, just as one’s body is continuous with objects or lofty ideals that are immune to criticality or accusations of theatricality. And if indeed theatricality is the most terrifying specter, why not deconstruct the theatricality of what we expect photography to do? We need it to reveal to us, via a showman’s surreal manipulation of the world and of photographic emulsion (or paint, in the case of the photographic tendencies of Rockwell), that which we are chidingly told we do not see. Deconstruction and criticism are the functions of a magician, not a Rock Chick, though, of course, both vape.