It might be unusual to begin a review by quoting a philosopher who lived some 2,600 years ago, but I am going to do so anyway. “Into the same rivers we step and do not step, for we are and we are not the same.” I was reminded of this fragment of Heraclitus while visiting “I am paralyzed with hope,” an exhibition at the Centro Botín that brings together works by Roni Horn produced from the mid-1990s to the present day.

After contemplating the beautiful title of the exhibition (a quote from comedian Maria Bamford), the visitor comes to a frieze of portraits of the artist, grouped into pairs. “A.k.a.” (2008–9) is a simple yet effective reflection on identity and intimacy. Taken from her private archive and juxtaposing youth and maturity in each pair, the dissimilar and identical photographed Roni meet and hold the viewer’s gaze. This thesis of identity as a category that remains the same as long as it changes — paradoxical and true: “we are and we are not” — is taken up again in “Still Water” (1999), a series of images of the Thames at different stages of its course through London. Installed around the perimeter of the room, the sequence generates a chromatic variation of greens, blues, and grays that receives its response in the waters of the Bay of Santander that can be seen through the fourth (all glass) wall of the room. As we get closer we notice that, seen up close, the images take on a geological, almost topographical aspect, and that their undulating texture bears a small numerical mottling, which refers to the meticulous captions in which the artist has added anecdotes and observations about the life of the river.

In the center of the room — and, sadly, surrounded by an anticlimactic cordon (security is sometimes the enemy of beauty) — one gold sheet rests on top of another. Between the layers, the light is refracted, producing a reddish hue. Gold Mats, Paired — for Ross and Felix (1994–2003) is a revision, in homage to Félix González-Torres and Ross Laycock, of an earlier piece that was composed of a single gold sheet. We shall revisit the anecdote: after all, little stories are what make History. During the last stages of Laycock’s illness, the couple went out to visit exhibitions: “We were blown away by the heroic, gentle, and horizontal presence of this gift,” wrote the Cuban artist. “A new landscape, a possible horizon, a place of rest and absolute beauty. Waiting for the right viewer […] Ross and I were lifted. That gesture was all we needed to rest, to think about the possibility of change.”

The overwhelming delicacy of this piece gives way to a mural of portraits of a teenage girl. Appearing at either end of the room, the artist’s niece allows herself to be photographed ninety-six times in the throes of puberty. The portraits, caricature-like, endearing and lighthearted, take on a monumental aspect through their installation as large murals. The domestic lightness of “This is Me, This is You” (1997–2003) clashes with the series of portraits of Isabelle Huppert (“Portrait of an Image,” 2005–6), whose calculated expressions produce a tension between spontaneity and self-consciousness in the room.

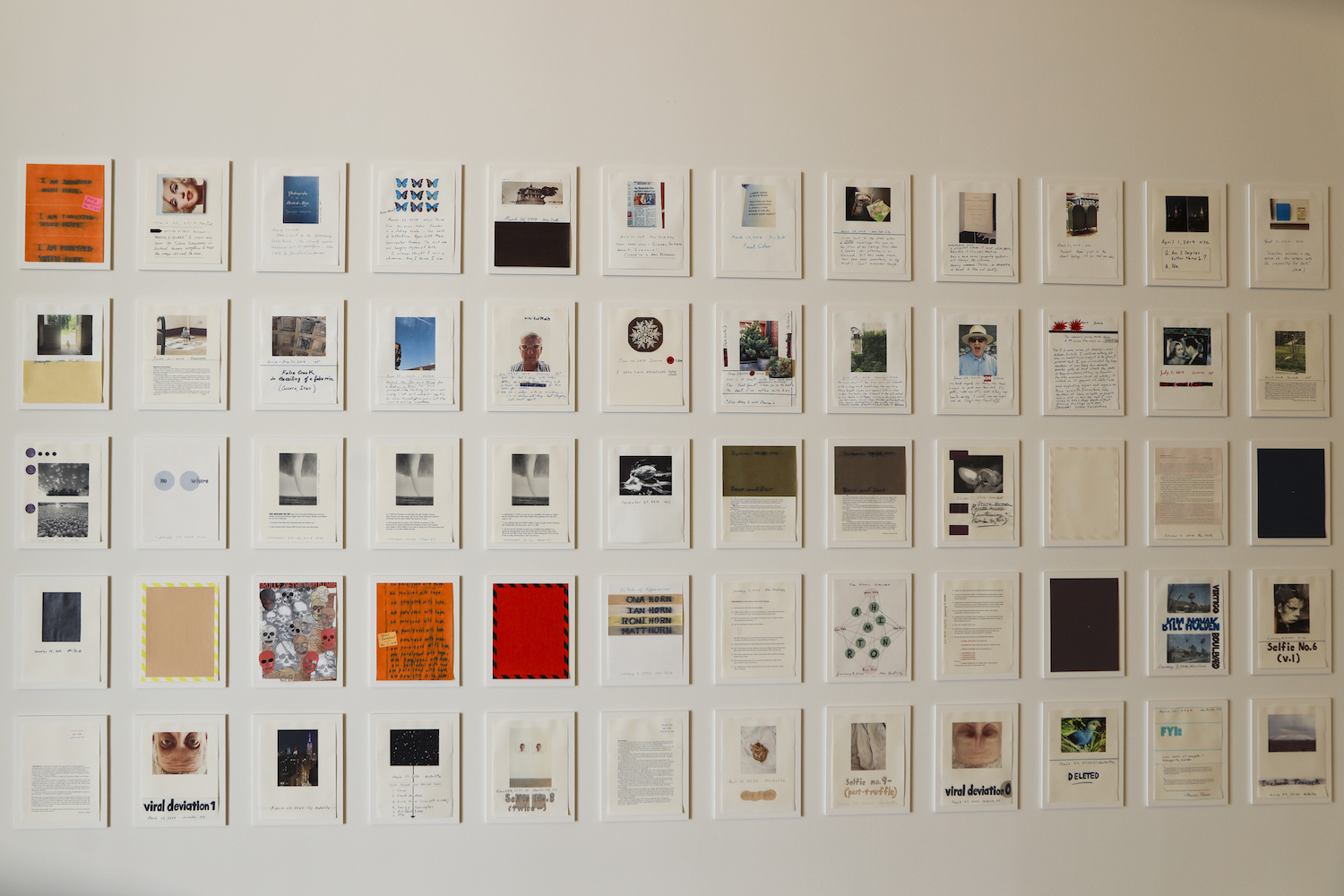

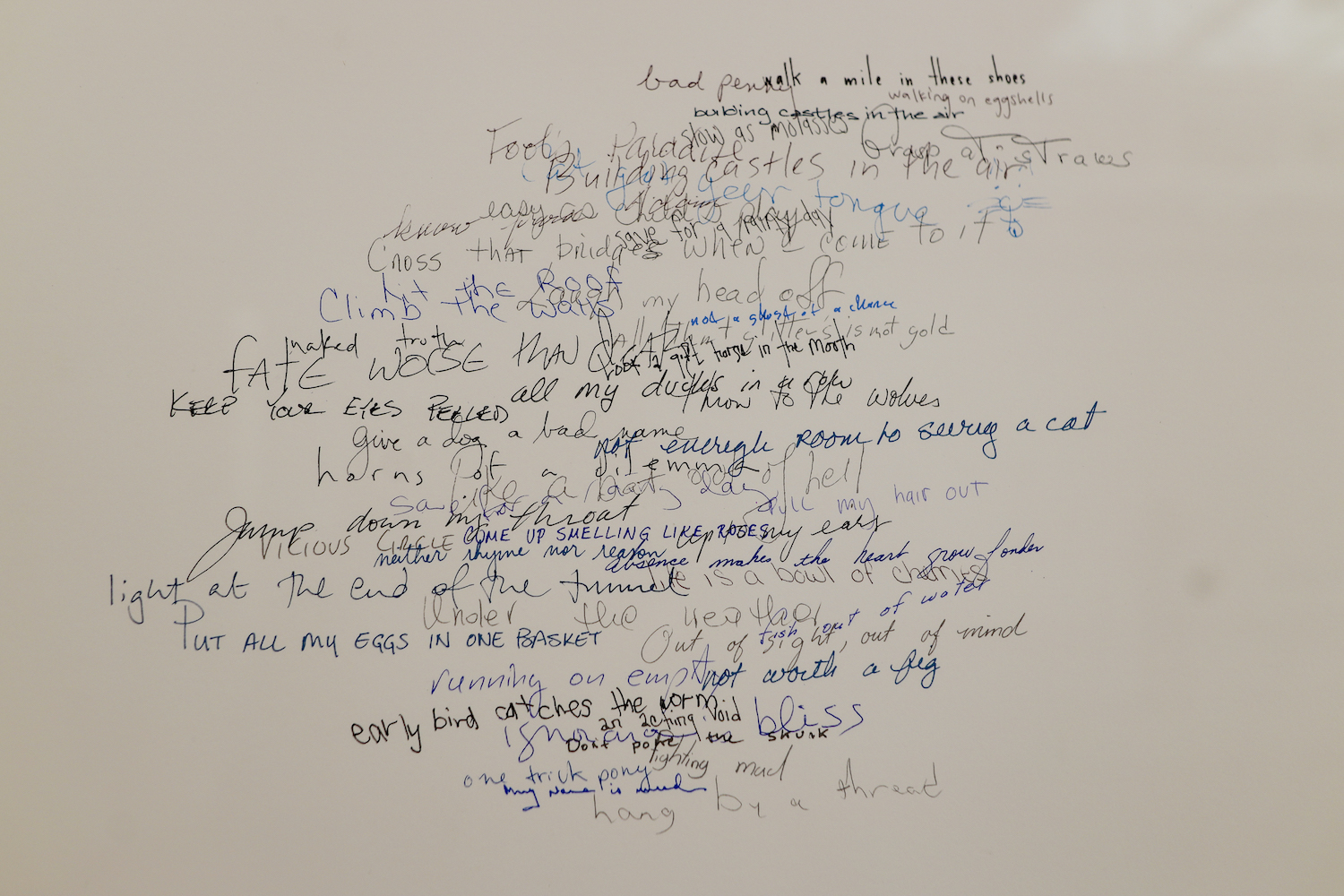

The exhibition continues with several wallpaper works. Cut out, reassembled, and riddled with puns (as in Th Rose Prblm, 2015, an exercise in permutations of the phrases “a rose is a rose” and “smelling like roses”), they are works that have the tedious aspect of craft. We notice something similar in the series “LOG” (2019–20), composed of drawings, collages, and jokes: despite its intelligence, it is presented in a long and exhausting saga of notebooks hung on a wall, considered as one of the Fine Arts.

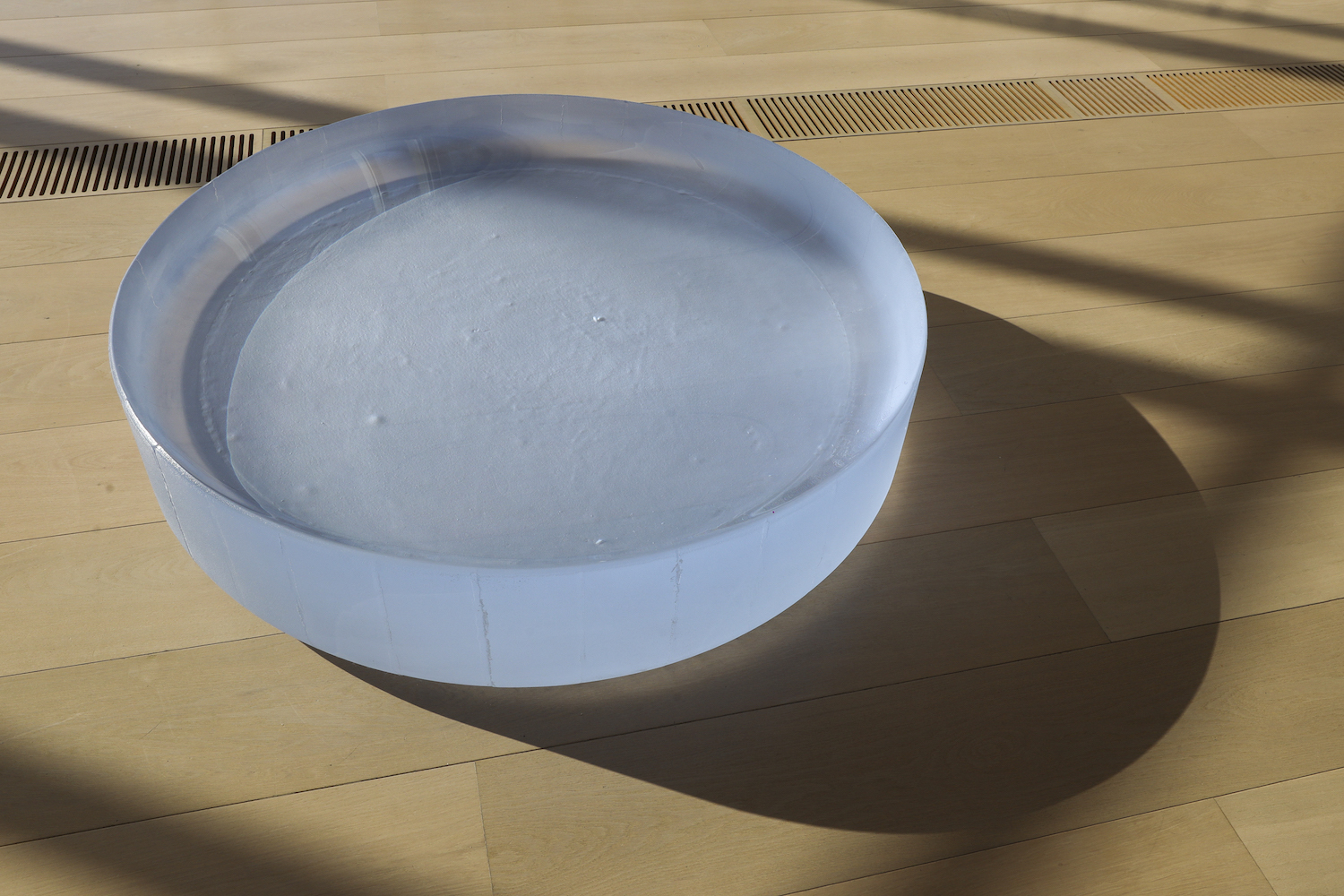

Horn’s work admirably alternates solemnity and lightness, exquisite and vulgar materials, seriousness and playfulness. All these oppositions seem to be summed up in the massive pair Untitled (“She was frightened of mice, snakes, frogs, sparrows, leeches, thunder, cold water, draughts, horses, goats, red-haired humans, and black cats…”) (2013–15), two large cylinders made from molten glass whose ostensible simplicity (and the play of title and subtitle gives us an early warning) does not stop the spectator from gawking, peering over the rough opaque walls to be dazzled by the translucent interior, observing how the concave surface apparently deforms its contents.