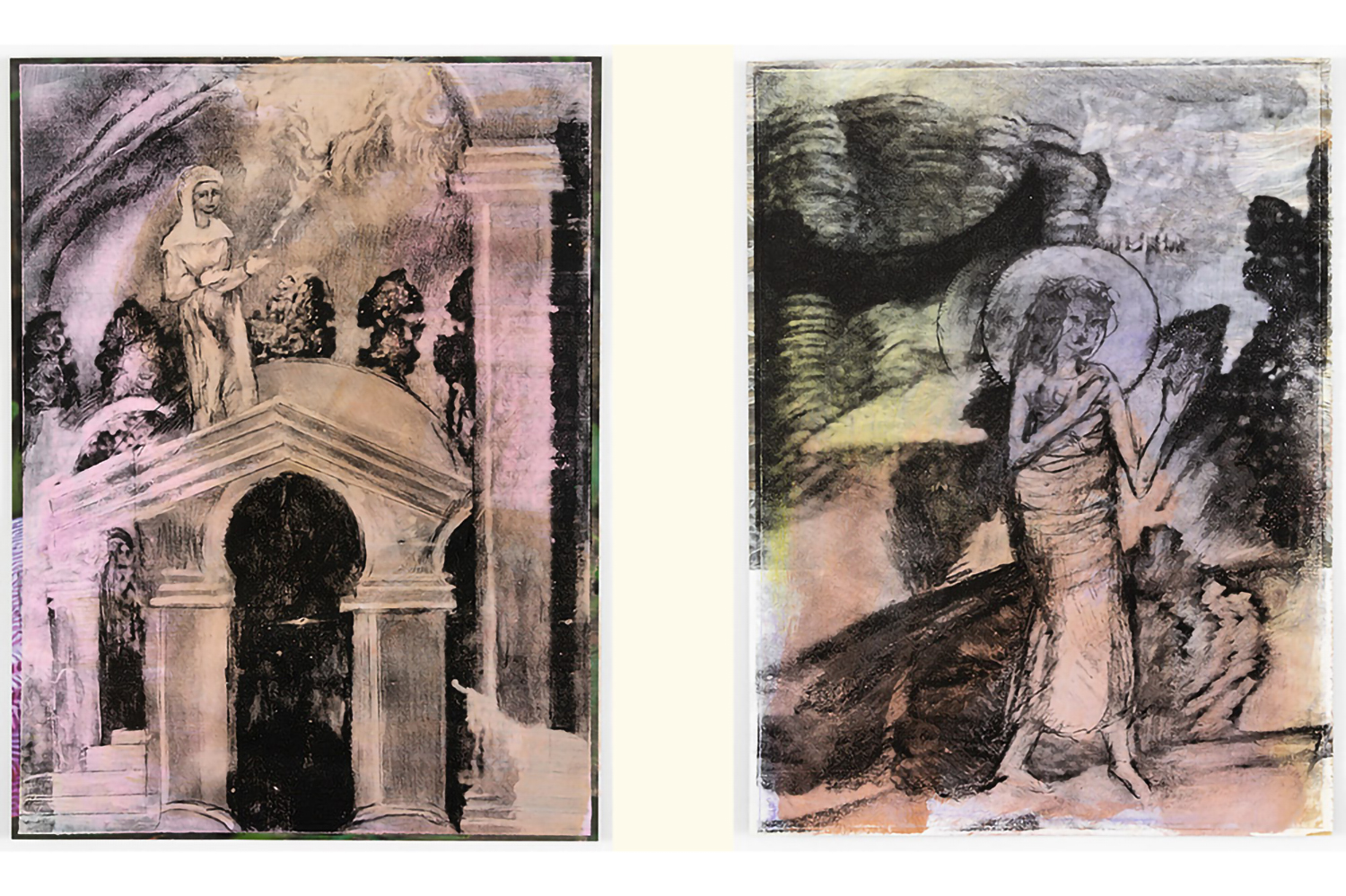

Wild lilies, sand, sourdough bread, tuna cans, gold, eye shadow, desert dirt: these are among the distinctive materials that Rochelle Goldberg sculpts into sensuous configurations. Spanning the organic and inorganic, these things become re-enchanted in “Psychomachia,” bearing a narrative of gestures across their fragmentary forms. A central series of prints, “The Life and Death of Mary” (2020), anchors the exhibition’s context around the biblical story of Mary of Egypt, a prostitute whose repentance and conversion prompted her self-exile in the desert. These haunting images portray the patron saint of penitence and evoke illuminated manuscripts and the warm hues of Redon’s symbolist dream worlds. They underscore Goldberg’s timely interpretation of religion — still an avoided subject in contemporary art — that moves beyond perfunctory moral judgments and instead extrapolates the affective and gendered dynamics of desire, belief, forgiveness, and witnessing.

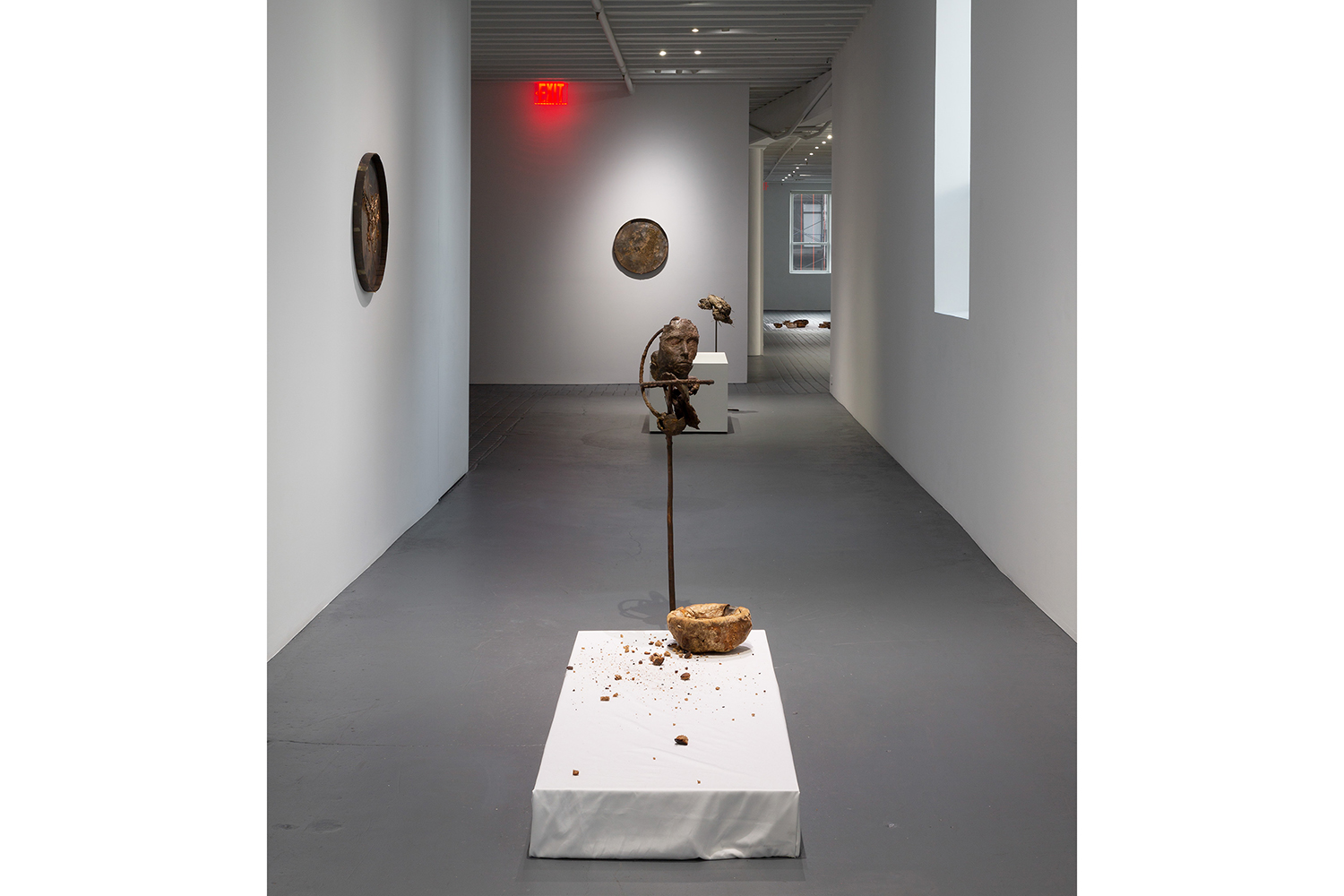

Goldberg’s floor sculptures reframe references to Mary as abstracted horizontal thresholds across the bounds of presence and absence. In Soiled [Resurrected] (2017–20), rectangular foam segments are coated with chia seeds and dusted with bronze powder and gold; the life-giving nature of seeds counters the sculpture’s aura of a sarcophagus to conjure a ritualized zone between the animate and non-living.

In Picnic (2020), Goldberg baked bread dough laced with metal coins onto glass bowls. These urn-like forms detail Mary’s material means of survival — from the prostitute’s monetary sale of her body to the mere three loaves of bread that she apparently subsisted on in the desert — and more broadly elicit burial objects and bodily remnants that compound the exhibition’s votive atmosphere.

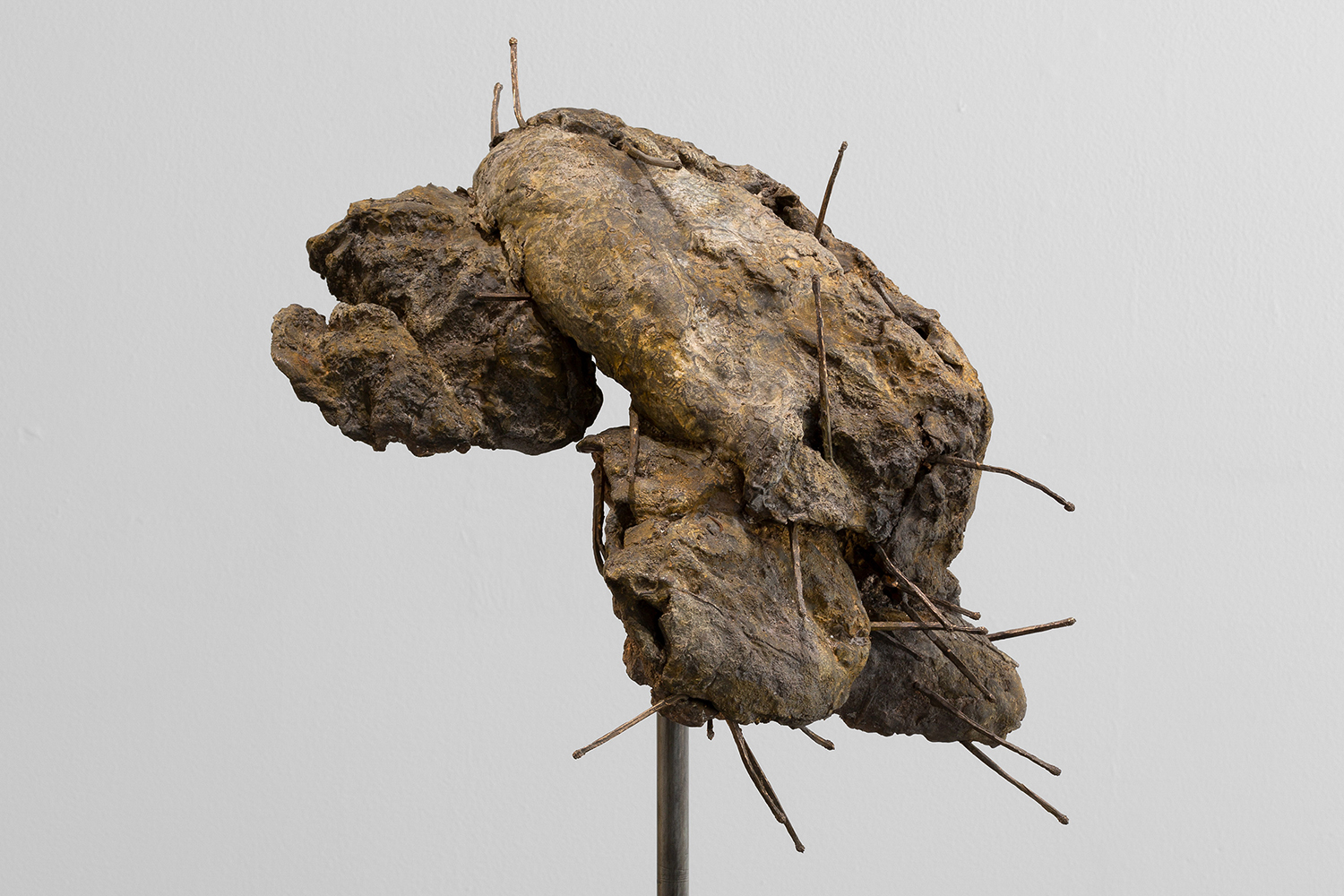

“Psyche” is the Greek word for “soul,” while “machia” means “battle,” and the exhibition’s titular “battle of the soul” is evident in Goldberg’s three Intralocutor sculptures (all 2020) — bronze busts tinted with colored eye shadow to recall death masks. Goldberg’s neologism “intralocutor” connotes a dialogue with oneself (from the Latin intra, “within” + loqui, “speak”), as opposed to with an interlocutor, an other. These sculptures depict what Goldberg describes as Mary’s “resurrection of her-self as her witness” upon death. Albeit mystical, I find the ethical questions raised by this reflexive act of self-witnessing and self-distancing resonant amid today’s intensified precarity: How can we witness, attune to, and transfigure the unmarked borders of life and death? To whom must we speak within? What subject positions and structures must we release in order to risk being forgiven?