In April of this year, the Hammer Museum expanded its real-estate footprint to include a former City National Bank at the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Glendon Avenue. To access the space, visitors must exit the main museum atrium and follow a series of stairs, elevators, and ramps, eventually entering what looks like an ’80s corporate lobby with shiny black marble floors and a security desk. The space is hardly recognizable as a museum gallery. Rather, it appears to be a bank in an advanced state of decay: the lights are off except for one overhead fluorescent unit, the chipped flooring reveals cracks in the concrete, the ceiling is stained with moisture, and there are pools of water on the floor.

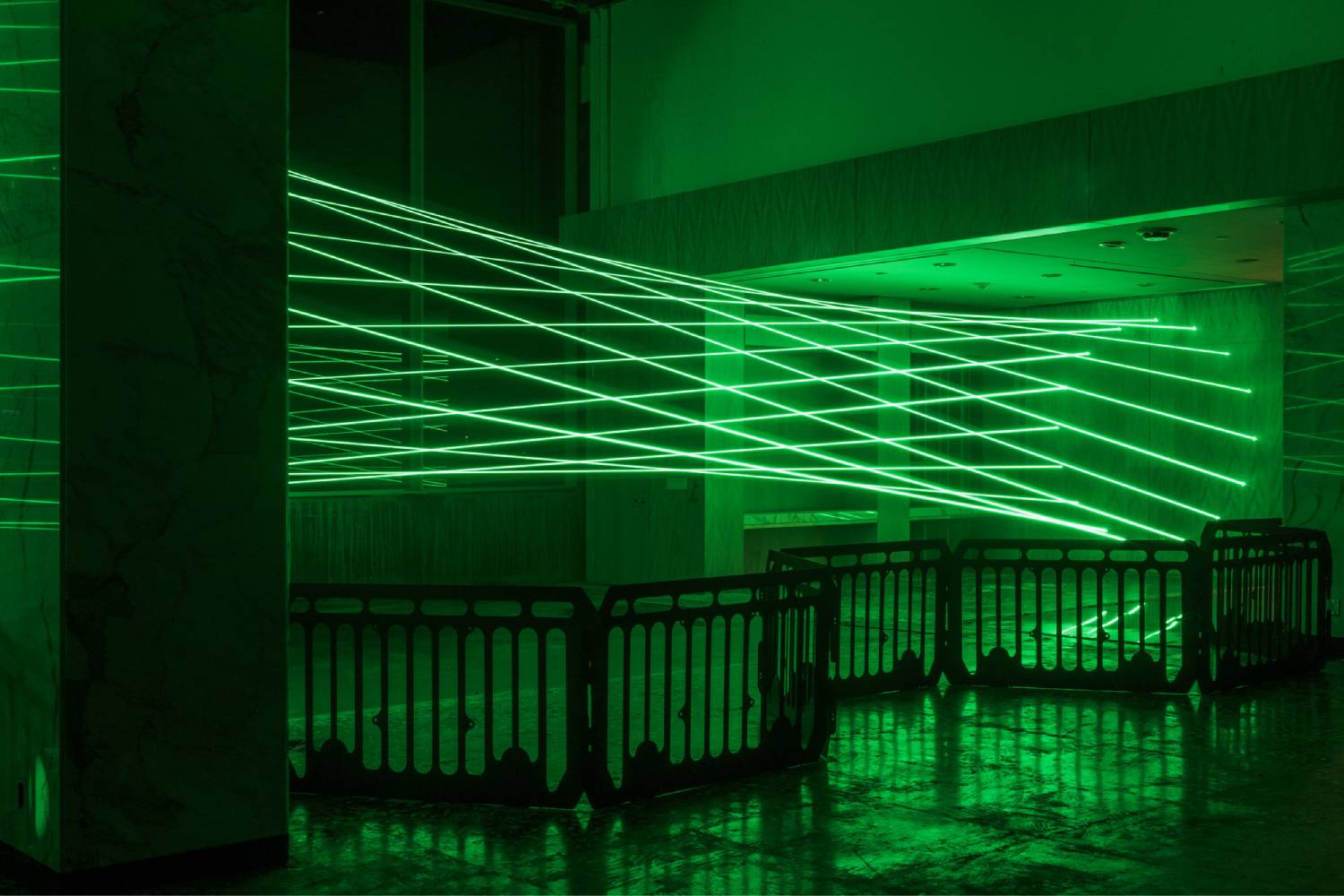

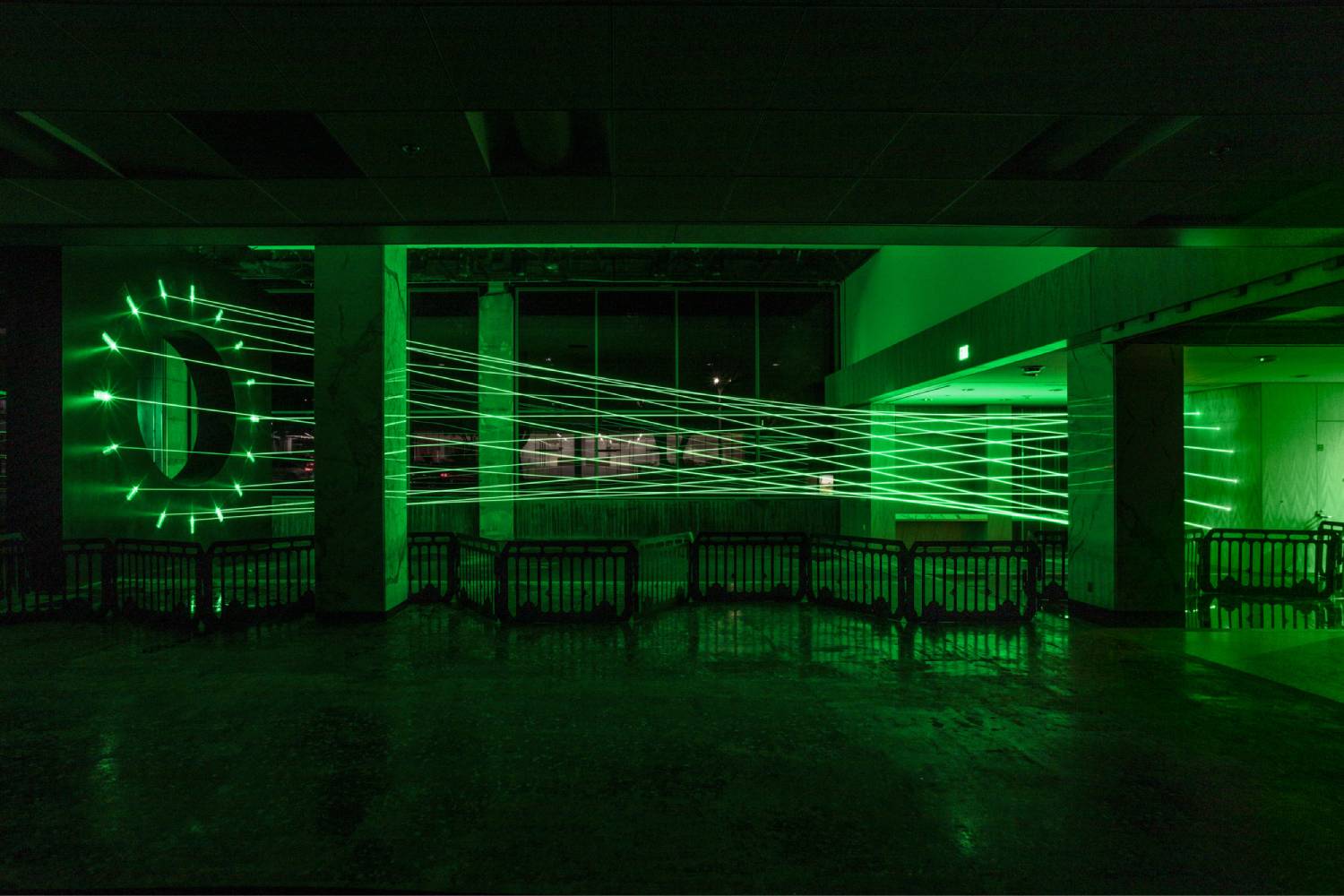

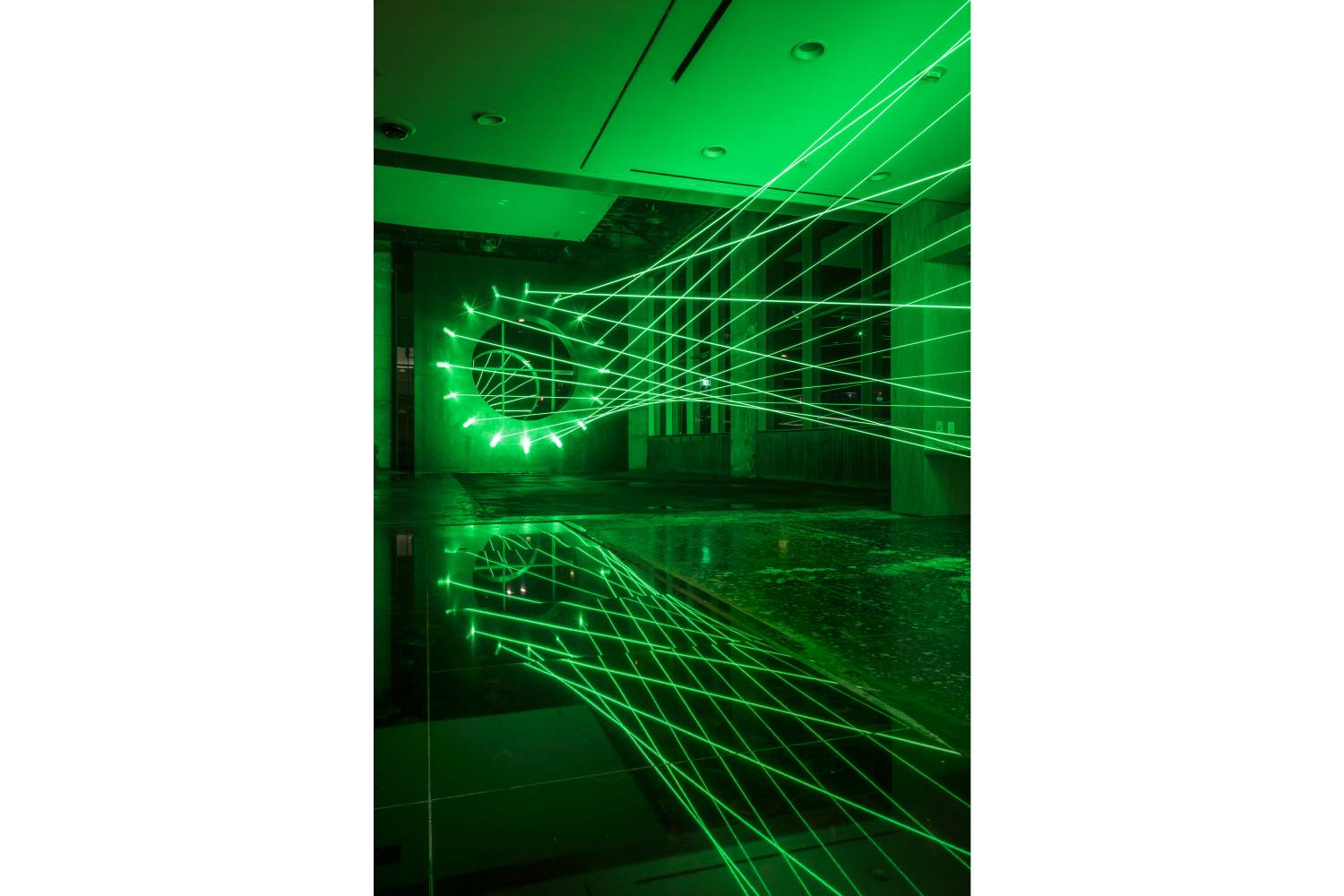

Amid this decay, or perhaps acting as its primary participant, is Rita McBride’s installation Particulates (2017), whose materials are listed as “water molecules, surfactant compounds, and high-intensity lasers.” The work, installed here in its third iteration after being displayed in New York and Liverpool, is a formation of sixteen lasers that create a kind of parabolic shape projected from one end of the space to the other. The beams of light emanate from a freestanding wall with a hole in the middle, and continuously interact with the water vapor being released into the atmosphere. The mist being sprayed into the space makes a hissing sound and causes pools of water to accumulate on the floor. The laser light quivers with the movement of dust particles and water vapor; one is made aware of the surprising concentration of stuff suspended in the air.

Evoking the setting of a cheesy spy or heist movie, the shape generated by the lasers, when viewed from one end of the room, resembles the barrel of a pistol, not unlike the iconic James Bond logo. The former bank’s vault looms on the other side of the room. The work has almost the quality of a booby trap, an apparently unassuming object that contains destructive power. One might imagine a character performing an over-the-top choreography to avoid stumbling into the trap and being exposed or harmed. The lasers are installed just beyond marble columns and are made inaccessible by an unassuming gate that surrounds the sculpture. Although its boundaries appear to be deceptively simple, in fact the work incorporates the air that visitors breathe, the light from the Los Angeles sun, and the dust particles that are constantly shifting inside the space.

Merging these aesthetics in a space seemingly under construction, one can’t help but consider the symbolic or critical implications of this setting — a new gallery in an old bank, the museum and the bank both revealing a condition of decline. What might this suggest about the state of the museum and its relationship to corporate capital? Is the museum, much like a bank, merely a storage facility for the rich? Are visitors witnesses to the decline of the public museum? Cash — physical cash — is becoming nearly obsolete; with nothing to contain, there is no longer a need for a vault. But corporate capital has become more insidious, immaterial, and difficult to understand. McBride activates these questions through this subtle experiential work of art that can only be understood through the body’s presence in the space. The money-green light, a constant hissing, and a slow, echoing drip provide an eerie visit to the museum.