Visiting Richard Prince’s retrospective at the New York Guggenheim Museum is like gorging on American culture. Everything is American, American, and American again. All the clichés of American mass and crass culture are in this outstanding exhibition: custom cars, lonely cowboys, bikers, girlfriends, jokes, cartoons, celebrities, money and all the miscellaneous Americana you can think of.

Covering about 30 years of work, this vast retrospective, organized by the Guggenheim’s chief curator Nancy Spector, reviews all of these iconographic categories through various phases and series of works, juxtaposing and finding new associations among them.

The two sculptures that open the show on the ground floor are monuments to high and low American culture: a hood from a late ’60s car, extracted and turned into a minimalist work referring to both American art history and muscle-car culture; and a column of tires like a spontaneous artsy tribute to the architecture of the museum.

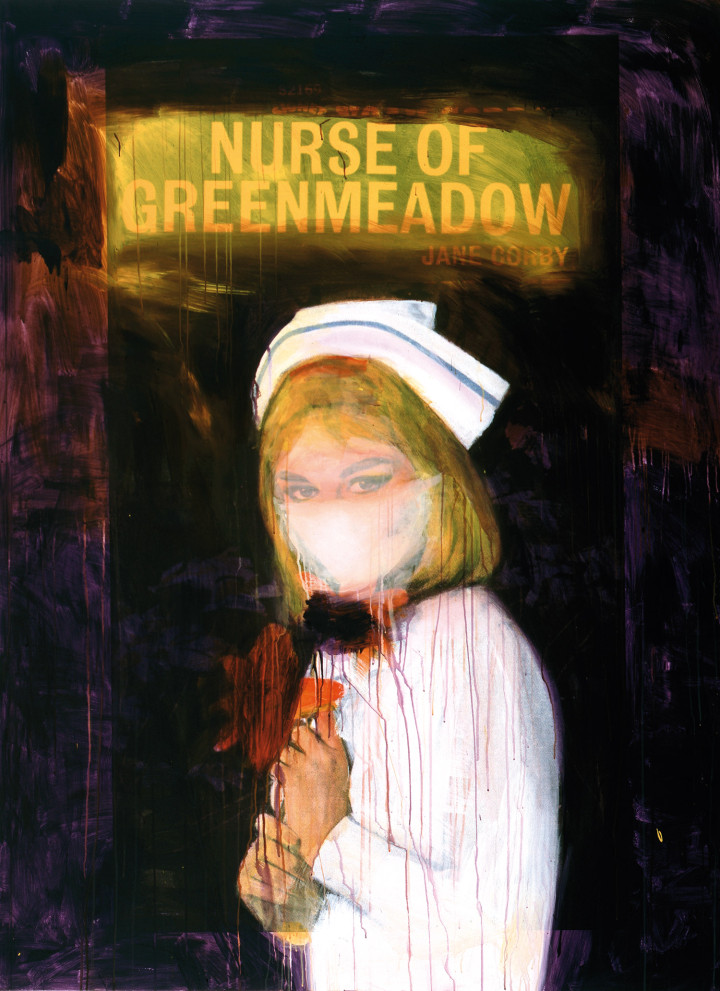

Chapters develop while walking up the rotunda: Cowboys, Gangs, Jokes Paintings, Check Paintings, Hoods, Girlfriends, Nurses, etc. The Cowboys, for instance, were already an archetype of the American hero, lonely and gutsy in the harsh desert, studied by Hollywood westerns. They were the subject of Andy Warhol’s ironic glance in the movie Lonesome Cowboys. But Prince, almost 12 years later, starting in 1980, pushed things forward with the photographic series “Cowboys” — photographs of photographs from the Marlboro Country ad campaign, featuring the Marlboro Man in different settings. The Marlboro cowboy here embodies a classic American icon, though removed multiple generations from its source.

Appropriation is today a standard practice for artists, but in 1977, when Prince re-photographed photos from a luxury furniture advertisement published in the New York Times Magazine, it was still a transgressive act, a new way of thinking that he shared with colleagues like Cindy Sherman and Sherrie Levine. Postmodernism was the ism of the day, and appropriation was its major concern, raising questions about originality and authorship.

“Untitled (Upstate)” is a recent series of photographs. He started it when he moved to Upstate New York, marking a shift of interest towards the ordinary surrounding reality and rural landscape.

But the most recent series consists of new paintings referencing Abstract Expressionism, in particular Willem de Kooning. They are a coherent continuation of the “Nurse Paintings,” although less powerful.

Prince both adheres to and critiques American mass culture. The exhibition shows his simultaneous repulsion and fascination, and successfully highlights the promiscuous relationship between the rawness of counterculture and the brilliantly polished surface of mass culture and consumerism.

One image in the show functions symbolically for the whole: it’s the famous photograph of naked, prepubescent child-actor Brooke Shields, appropriated by Prince in 1983 and titled, like the exhibition, Spiritual America. This picture, with a history of its own story (Shields later tried to stop circulation of the image, originally taken with her mother’s consent) is like a prism that refracts moralism and consumerism, puritanism and pop culture, transgression and conformity. This multi-sided reality was, and still is, at the core of his work.