Sometimes people are simply cool. You know what I mean: when you meet someone, only to be struck by a certain compelling energy, which is at once zeitgeist and timeless. What constitutes such a state is hard to pin down, but it might include a soft self-assurance, passion, talent, personal style, and, well, a certain je ne sais quoi. All this is to say: Pol Taburet is strikingly cool. He’s also hard to pin down, which isn’t surprising when you consider his upcoming schedule of exhibitions in 2023 alone. Taburet has shows at Balice Hertling and Lafayette Anticipations (both in Paris), a residency at the Pivô in Salvador, Bahia, and solo presentations at Longlati Foundation in Shanghai and Mendes Wood DM in São Paulo. Not bad for a twenty-six-year-old.

Born in 1997, Taburet grew up in Paris and received a bachelor’s degree in painting and ceramics from the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Paris-Cergy, before going on to take their MFA program. He earned his first solo exhibition at Balice Hertling’s former space on Rue Ramponeau before he even graduated in autumn 2020. This was soon followed by a one-person show at C L E A R I N G gallery’s Los Angeles space. Quickly thereafter Taburet’s work was acquired by the Pinault Collection. All this happened before his twenty-fifth birthday, which led to accolades that included Artnet News calling him “the next big thing.”1

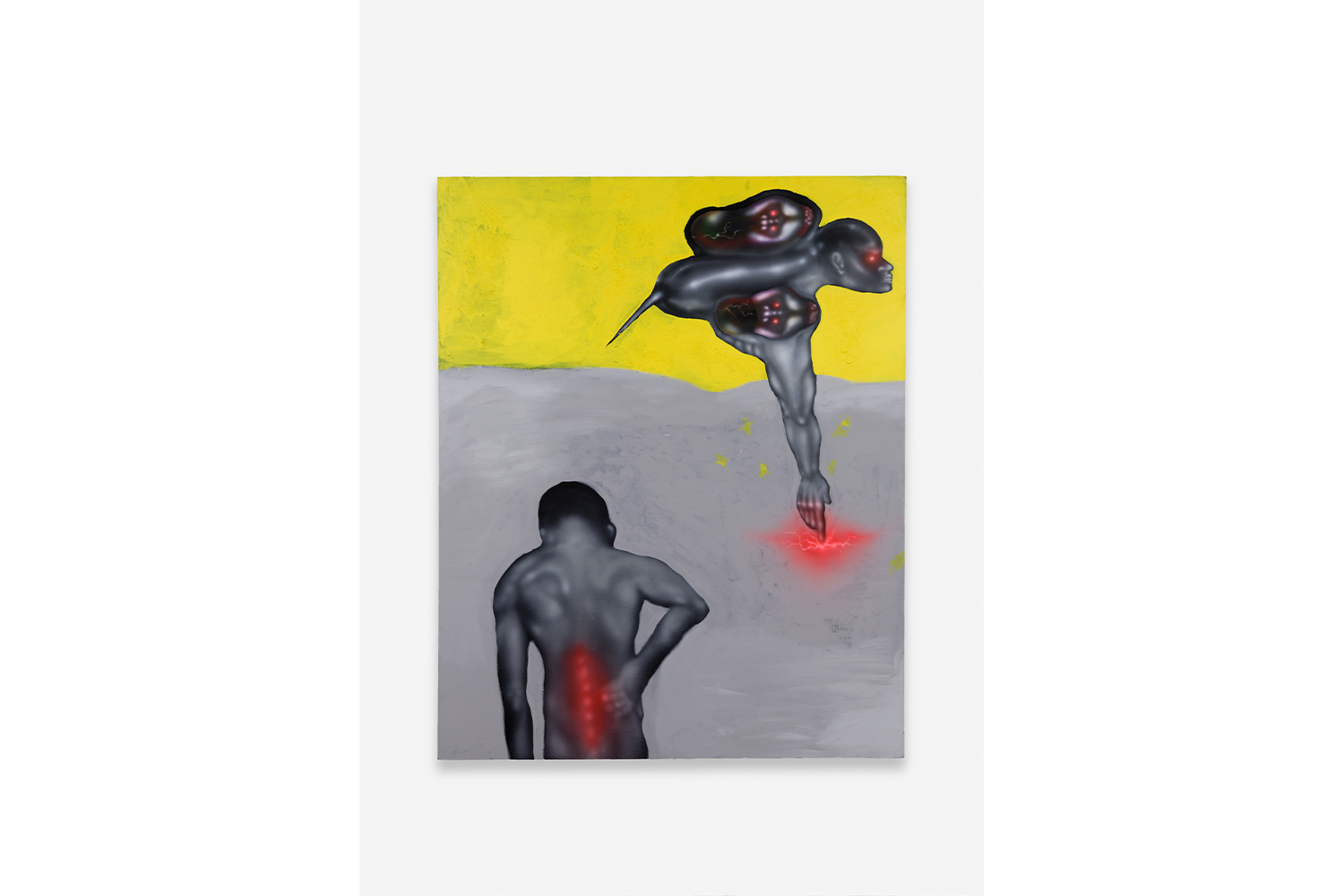

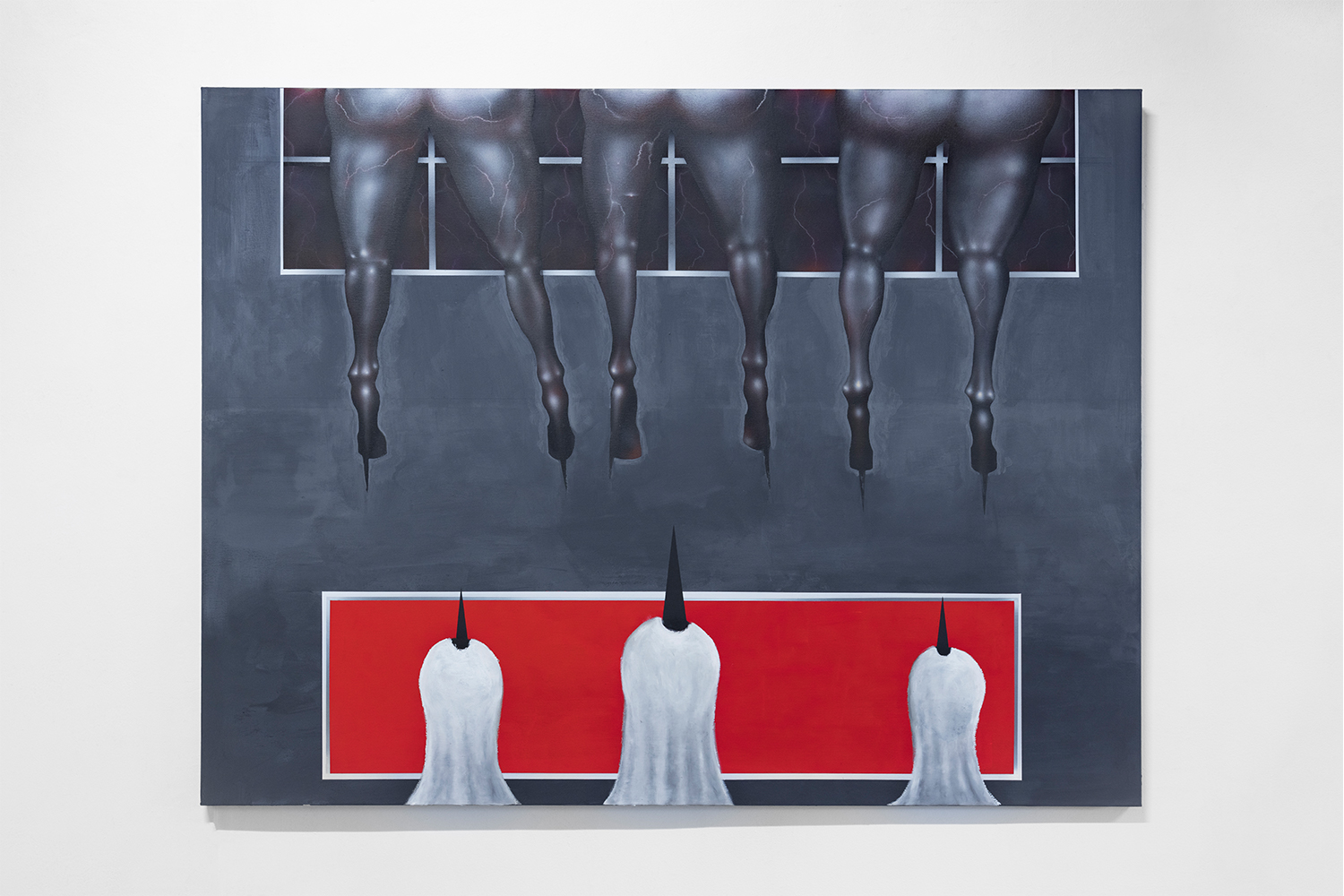

When I do finally meet Taburet over Zoom, the artist is in his Paris studio, smoking. Numerous large-scale canvases lean casually against the white walls: strange dark bodies that are neither human nor animal are in formation, emerging from planes of bright color. In one, Mud Field (2023), the canvas is divided into two parts: a moss-green wall and brown carpet divided by a skirting-board strip of gray. A face emerges from a red painting and another from a sideboard-cum-plinth, both bearing witness to a sarcophagus-like form lying concrete-stiff on the floor, baring its teeth. Influences like Frances Bacon can be keenly felt in Taburet’s nondescript interior spaces, delineated with a sense of structural intelligence and imbued with libidinal energy. Yet the contrast between the flat stillness of the surround and the hazy dynamism of the airbrushed faces — dark yet luminescent — also begets a strange Lynchian mood; something is amiss in this enigmatic universe. Other works, like Disguised Fly (2020), could be straight out of the brain of H. R. Giger: a horrifying insect with arms and a giant stinger — part human, part animal, part machine — has seemingly pierced a person with neon-pink venomous electricity, which now pulses up their spine.

Taburet works across a suite of paintings at the same time, manipulating the surfaces in a rhythmic way and moving between them, rather than focusing on individual canvases. “I don’t do any drawings before I paint. I’m projecting a lot and things are appearing automatically. It’s a very ‘jazzy’ way of working [rooted] in improvisation. You don’t know if the painting is going to be good or bad at the end, but you just have to make it work. In a way it’s like a puzzle.”2

He previously used oil paint as his main medium and would rotate the canvases as he went — adding, taking away, shaping and changing — but for the past two years he has used a new medium of alcohol-based paint combined with oil pastel and acrylic, which requires another way of working. Why the change? “A friend of mine, who is a descendant of Monet, brought me this weird liquid, like a resin with alcohol, and some blue pigments, and told me to try it. As soon as I used it on the canvas, the color was so intense. I’d never seen color like that, which also dried so quickly. I wanted to get fast on the canvas: to catch my eye and work on intense paintings, creating dramatic scenes.”

Oil paint is still a medium that the artist enjoys, but it appears at the end of the painting process: he works on faces, hands, feet, and body parts using an airbrush to create a misty, out-of-focus effect, then uses alcohol-based paint for what he describes as “the solid, inert, and minor things,” and follows this by rendering the clothing in oil paint. Taburet wanted to work without the burden of art history, particularly the weighted legacy of oil paint. “When I was painting with oil in school, whatever brushstrokes I would use, for me it was referring to a painter: if I used a lot of liquid or turpentine, it could be referring to a Peter Doig, or if I worked with brown brushstrokes, it would be like the beginning of a more classical painting. So it always has this direct effect [and link] to the big masters. This was new ground for me to try. It was same with the airbrush, which has more of an Afro or Latino history, so for me it was interesting to make it a history-of-art dialogue. I like to mix epochs.”

Taburet is quietly poised when mentioning the mass of work that he has to produce for the forthcoming shows — which includes his first venture into sculpture, creating figures in materials like bronze and resin — and astutely discusses the development of his style. After specializing in ceramics, Taburet’s foray into oil painting as his primary medium was born purely of necessity, as he didn’t have access to a kiln. “A lot of my work and choices are made like this. It’s about frustration in a way; the ideas I’m working on now I had a long time ago, but I have the capacity to do it now. For example, [take] the size of the paintings: I was working in my room for a long time, which was really small, but now the paintings have started to get a lot of air, as I can take steps back to watch them and feel them differently.”

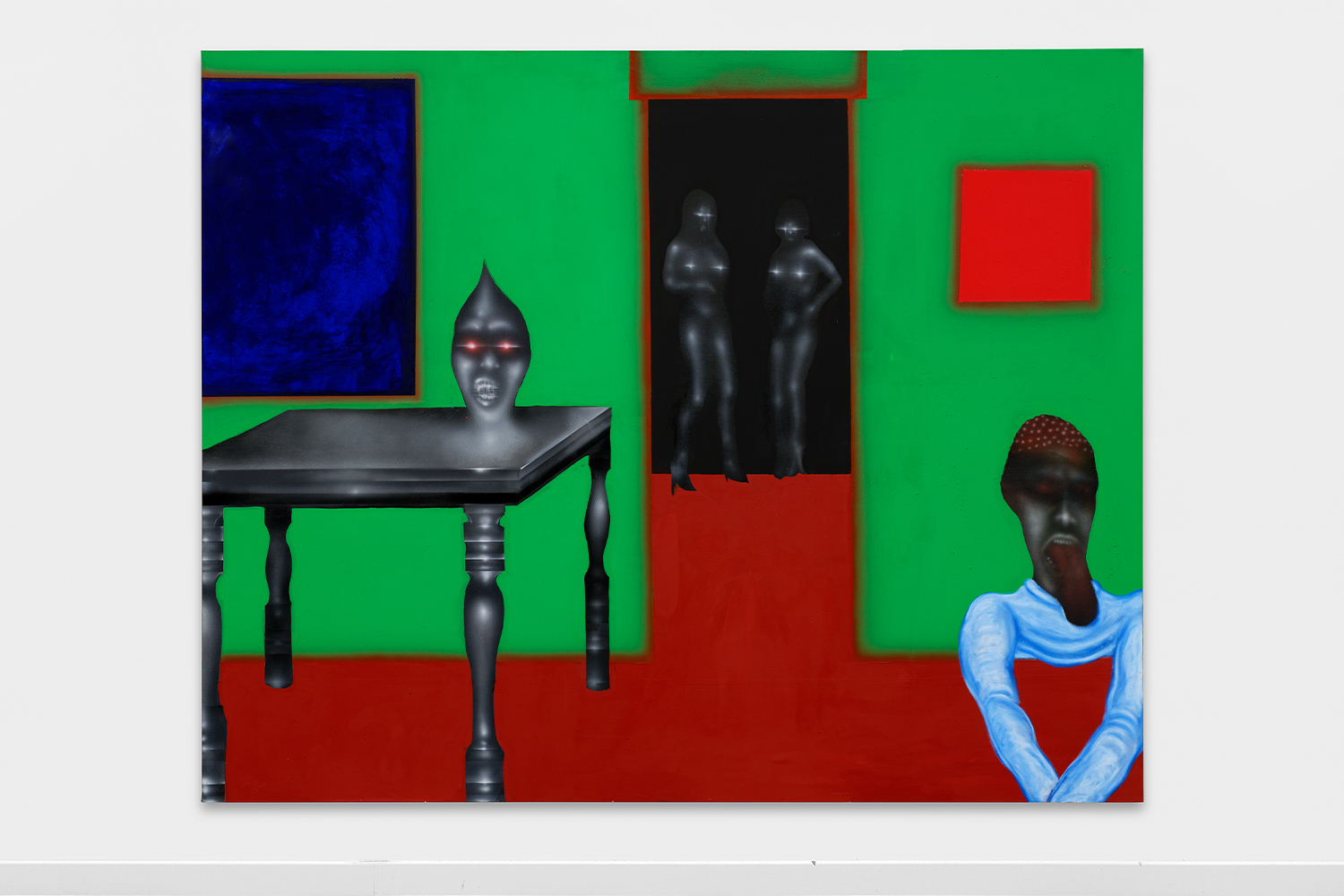

This room was in his parents’ apartment in Paris, where Taburet still lives, and he cites the relevance of this space to the themes and images within his paintings. “My mum has a weird old table which has an anatomic shape, and she puts fur on the couch, or a fake leopard pillow. She used to love animals like crocodiles, so the apartment was full of little objects, and through the objects you could see something that looks alive. I grew up within that environment, so at some point I think it was logical that [my work] would focus on this in a transformational way.” Such a table seems to feature in Buried On A Sunday (2021), which depicts a domestic room hung with monochrome paintings upon acid-green walls against a brick-red floor. A shadowy doorway reveals two enigmatic figures, white nipples and eyeballs glimmering against the darkness, while in the foreground, the table grows a pointed head — mouth open, eyes red like lasers. A giant tongue spills from the lips of another legless creature on the right-hand side. Are these monsters or creatures of the night? They appear to exist in a nebulous state, morphing from one thing into another, unfixed and reshaping themselves like mythological beings. In this sense, Taburet’s work is comparable to the likes of Wangechi Mutu, or younger artists like Frida Orupabo, both of whom envisage Black bodies as mutable entities comprised of multiplicities. By synthesizing corporeal fragments, new configurations of subjectivity are imagined, opening space for narratives that have been refused by colonial legacies.

Taburet stresses that, for him, such mutability has ancient roots: “Transformation in a mythological way has always been an inspiration to me. You can have an animal with a lion’s body and a snake’s head. That is a deep, never-ending inspiration. You can always mix things with things and create something. More and more, we live in a world where transformation is a big subject in every way: sexuality and the transmission of sex, or the transformation of the body with electronics, or the way we are transferring memory to a computer, where we extend our body to other totems or objects.”

The crux of the artist’s approach, he says, lies in this question: “At which point can you consider an object alive or not? An object has a life. At some point it is created, at some point it is destroyed, just like us. In voodoo you have a relation between plants and objects and the universe — what is not visible but still has an effect on us.”

Taburet’s grandmother had a religious Christian upbringing in Guadeloupe, and as a child he would attend Sunday Mass with her, through which he developed a love of religious paintings.3 There is a sense of different worlds colliding upon the canvas in his work: of religiosity meeting spirituality and ritual, nourished by Taburet into a melting pot of transformative potential. Read through this lens, the two figures in Buried On A Sunday are reminiscent of Masaccio’s Adam and Eve driven out of paradise; but here, their harrowed shame mutates into sparkling wonder, bodies shining with intent at exploring a new world. Similarly, A Sacred Pit (2021) — a vertical canvas delineating a doorway through which there is a bright blue sky and a terrifyingly bulbous mouth, all teeth and tongue, bone and skulls — could be purgatory, or worse, the cavity to hell, which nonetheless glistens with a bizarrely seductive power. For his exhibition at Lafayette Anticipations, which opens on June 20, Taburet doubles down on this mood of unworldliness that is underpinned by a sense of narrative storytelling or journeying. He says: “On the first floor it’s an intimate story, but also a general human story about our intimacy: in love, in life, in violence.” Taburet emphasizes the sense of dramaturgy that he wants the viewer to be guided by as they walk through the show. “The whole exhibition is like a cinema or film set with doors and domestic apartments, as if you’re intruding into three-dimensional paintings. There is no natural light on the first floor, so it’s very artificial, like a dream or nightmare or hallucination. On the second floor it’s more of an enlightening moment, full of natural light, and there’s a weird temple in the middle of the room with a beast under the table… There’s something that’s religious or spiritual in this room, something more powerful.”

The exhibition title, “OPERA III: ZOO ‘The Day of Heaven and Hell,’” winks at a theatrical journey through various dimensions, or between life and death — reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno, moving through worlds in a process of recognition and rejection, of sadness and happiness. Taburet acknowledges that “there is something religious in it… you always find this dimension in religion, of your acts on Earth having repercussions in the afterworld. In a painting I’m working on at the moment… you have moments where ghosts or weird angels appear at the same time as [living] humans. I have a fascination and a fear of that.”

Taburet’s journey is arguably more akin to Arnold van Gennep’s The Rites of Passage (1909), a ceremony or ritual of passage that occurs when an individual leaves one group to enter another, involving a significant change. Van Gennep describes the passage of social regeneration — of birth and death into rebirth — as being defined by three states: separation, liminality, and incorporation, and uses the metaphor of “a kind of house divided into rooms and corridors”4 to describe this journey. Seen in this light, Taburet’s interiors become the setting for van Gennep’s mode of transformative ceremony, bodies manifesting within the realm of liminality, in-betweenness, and the excitement of uncertainty.

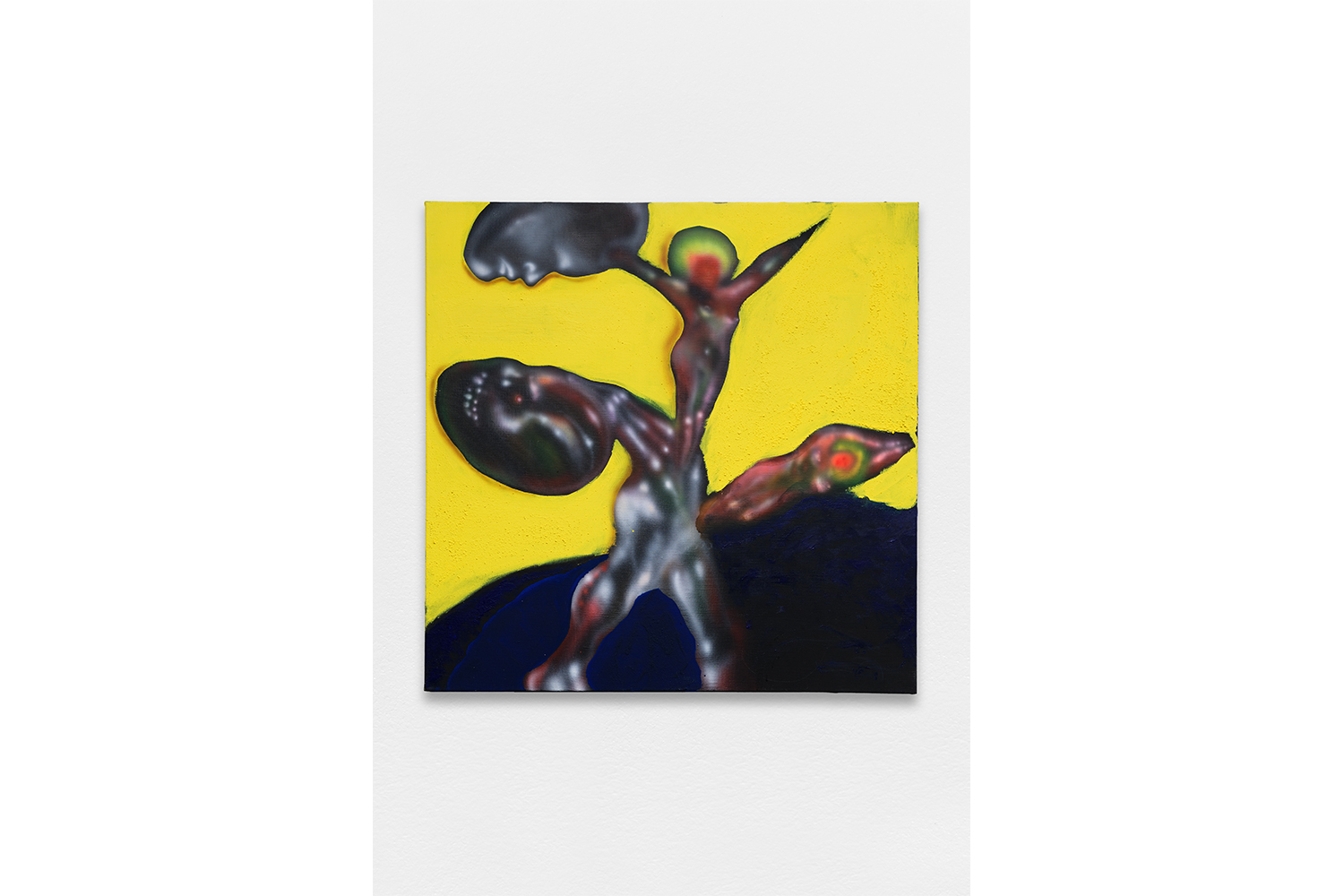

Taburet’s painting Fromager (2020) is one that has stayed with me, working its way into my brain. It depicts a plantlike form with bones and nodules comprised of skulls, faces, and roots, but, most remarkably, androgynous saint-like figures with florescent, hazy haloes, who are attempting to ascend to the heavens amid a mustard-yellow sky. It is somehow everything all at once, yet also amid a process of unbecoming: it is beautiful and disturbing, holy and human, male and female, animal and vegetal, all and nothing. And this is the most intriguing aspect of Taburet’s art: it envisages a modern mythology in which the body can be anything and everything, with a subjectivity that is wholly mutable: not only subject to change, but willing it, relishing it, devouring it.