“Curator” is a pretty new word. It has made its way into dictionaries over the past few decades, and we only started talking about “curatorial studies” in the 1990s. But hey, we’re all about new methods and attitudes around here. For our new column focusing on experimental curatorial and editorial approaches to gallery culture, we played around with words. We present “The Curist.”

I first came to O-Town House, Scott Cameron Weaver’s gallery and project space in the MacArthur Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, in 2019. I expected to slip in and out, but I stayed for at least two hours talking with Scott — I narrowly escaped my car being towed. This visitor experience is a common one at the gallery. It’s hard for anyone to get out of there without having a cigarette and a cocktail on the terrace. (I have since made sure to go at the end of my day of gallery hopping.)

The show that I saw during that first visit was John Boskovich’s “Psycho Salon.” Much of the work hadn’t been shown since the 1990s or at all. I hadn’t known of the artist before, but my interest was piqued by the re-creation of his living room inside the gallery. It was a strange and haunting installation of Boskovich’s own furniture

and artwork intermingled. It was clear that Weaver had committed himself to displaying the work of the late artist with care, rigor, and intention.

With the shows he’s organized since — with James Benning, Nora Schultz, Adam Stamp, Ciccio, Sarah Szczesny, Bruce Yonemoto, Mark Verabioff, and others — Weaver has managed to create, maintain, and cultivate an auteur approach to art dealing that seems rare in a hyper-professionalized art world. The shows are often driven by a kind of desire — a personal, intimate nor curiosity — on the part of their custodian. There is never fussiness, nor is there sloppiness either.

The gallery is in a townhouse, and there’s an O-shaped window in the downstairs gallery. The window’s presence is a constant, but each artist that exhibits must collaborate and contend with the unpredictable light it provides.

Scott and I talked on the terrace just like any other visit to the gallery. When I

left that day, he gave me a small pineapple, the universal symbol of hospitality.

Gracie Hadland: When did you move to Los Angeles? And when did you start the gallery?

Scott Cameron Weaver: I moved here from New York in the spring of 2018 after having been there for a little over two years. It was partly on a whim, but it was also to get out of New York. I was coming out of a dark time in the city. I had worked in museums as a curator and worked at galleries as a director. And I was disenchanted with both of those things. So, when I came here, I was allergic to that word “gallery.” Somehow, I just wasn’t wanting to align myself with the rubric of the gallery, per se. I placed all of that anxiety, I guess, onto that word. I did eventually get over that, obviously

GH: So did you just start doing shows in your apartment?

SCW: I was looking for a space where I could also live; I thought that was a nice model that I’d appreciated over the years from different places like Barbara Weiss and the exhibition space I helped open with Alexander Schroeder, Mehringdamm 72 (MD72). I also thought that the social space was an additive one in terms of an art narrative. Part of that was also the fact that I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. I had no idea what I wanted to do. I wanted to open a space, and I wanted to do shows, but I didn’t really have a plan. I didn’t want it to be like, “Okay, I’m moving here from New York, here’s my program; here are my artists.” I thought that was the wrong attitude. I wanted LA and the space to tell me what it needed or wanted to be, and through the social aspect of the space it came together. Which was half honest, I guess, because in a way it was kind of wishy-washy because I didn’t really know what I was doing.

It was kind of random what I ended up doing at first. Gerry Bibby was here on a MAK Mackey Apartments residency, so that was one of the first shows. And I had just produced that Cerith Wyn Evans neon piece, which is the one I actually opened with. It read: “I call your image to mind…” backwards, so the text could be read reflecting in the windows looking out onto Los Angeles. I thought that was a good way to conjure something into existence. Then James Benning approached me. I had worked with him many times before, and when he found out I was in LA and opened the space, he said, “Oh, I have the perfect show for O-Town House.” Around then I was reading a book and found out that Suzanne Jackson had Gallery 32 in this building fifteen years prior. So, one thing led to the next, and a program emerged out of that. I still don’t have an artist list per se, but there is a corral around a bunch of artists that I work with continuously or repeatedly in different ways.

GH: How did you find this space? Can you talk a little bit about the history of the building?

SCW: At the recommendation of a friend, I came to get my haircut here and I walked into this building. I was like, “What the fuck is this magical place?” I couldn’t get that upstairs-downstairs idea out of my head. I was already thinking about opening a space, but it was all very abstract. I hadn’t really looked at anything else at that point, and then once I was here, I was like, “This is so special.” It was built in 1927 as “The Granada Shoppes and Studios,” and it was the first live-work building on the West Coast. So, it was for artists or artisans to have their studios and live upstairs. George Hurrell had his photography studio down here for three or four decades. There’s a lot of weird, storied history in this building, as it turns out. It was landmarked in the 1980s.

GH: Where did the name O-Town House come from?

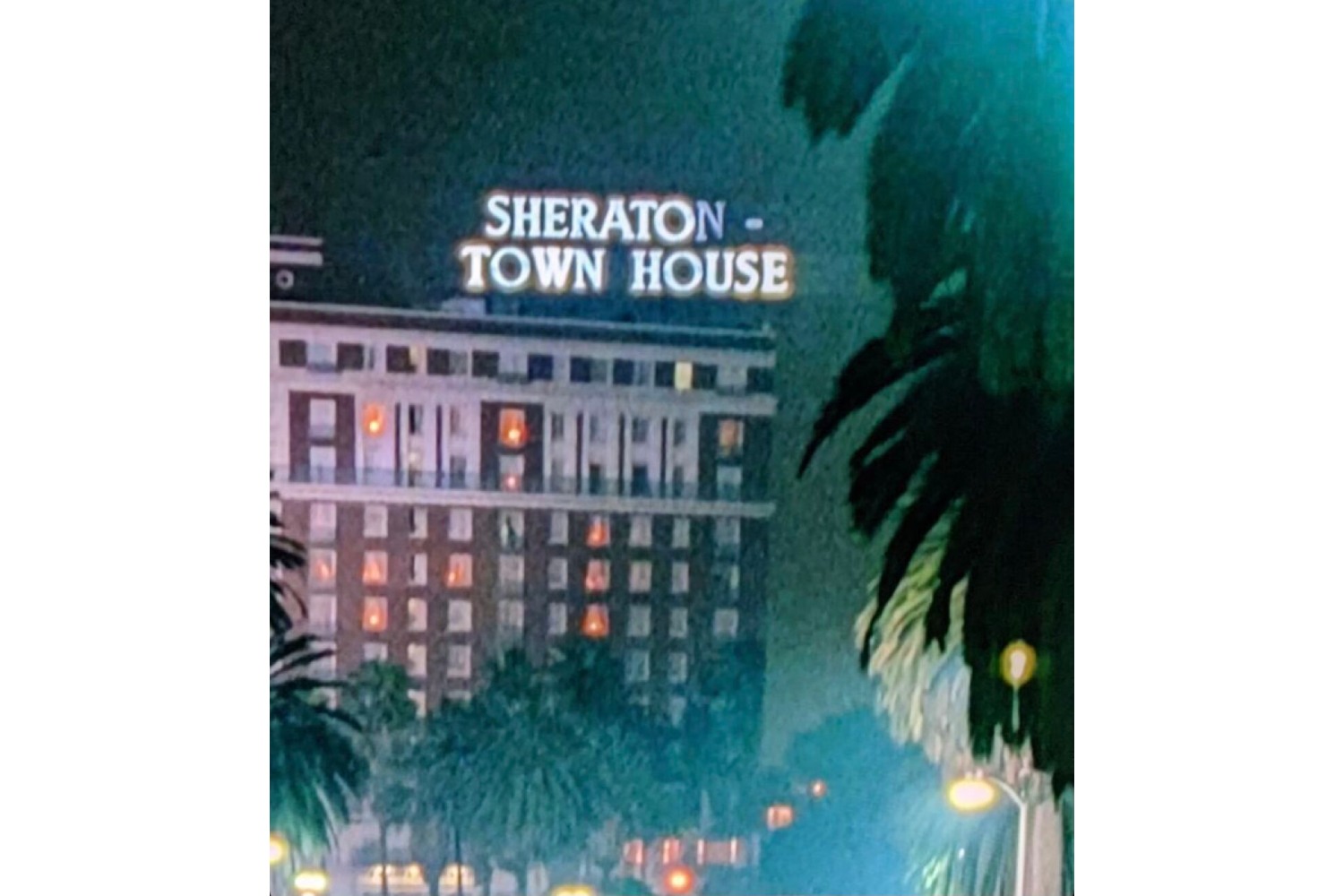

SCW: When I moved in here, I was like, “I have no money, and I have no plan. And I don’t even have a name for this space.” It was a pretty low-fi operation. I mean, it still is, let’s be honest. But in the spirit of letting LA tell me what the space should be, I took the name from the sign across the street that you can see from the terrace. It was what I call my “Ed Ruscha moment.”

It used to be the Sheraton Town House. It was built in 1929 as an apartment building but changed very quickly into a hotel which was run by the Hiltons for a long time. It was once very fancy. Elizabeth Taylor got married there. I don’t know at what point it turned into the Sheraton Town House, but it closed in 1993. It was going to be torn down, I think, in the early aughts, but the LA Conservancy stepped in and it became lower-income housing. I guess Sheraton just took down the other letters of “Sheraton.” This guy I know who lives in the building says they’re all in the basement now. It’s very weird — not sure why they would leave just the “O.”

GH: I remember when I first came to the gallery — I had just moved here and a whole group of LA people opened up to me through O-Town House. A lot of my LA community came from attending shows. Adam Stamp, Erica Redling, Larry Johnson, Hedi El Kholti, and so on… It’s a widespread community but also a kind of niche who all found each other and come in and out. Coming here dispelled the cliché that everyone in LA is dumb and vain. Everyone is also very serious in a way.

SCW: That’s part of what I hoped for: a social space can remind us that there are other systems of value within art beyond just market value, and that, of course, comes only by taking it all seriously, making good shows and being capable (or willing) to engage in interesting conversations with people. I love the unpredicted meetings-of-the-minds and how unexpectedly fruitful they can be! Oftentimes, it’s really stressful for me. “Oh, no! How are all these people going to fit together?”

GH: But then they kind of figure it out.

SCW: Right, and that’s super interesting. It makes me really happy to hear you say that it was formative to your early days when you were laying a map of LA. Because in a way that’s what I did too. It’s how I created a map and a community network; that was its function.

GH: Yes, and it kind of happened organically. You weren’t organizing it in this way where you had said, “We need to get the coolest people in here.” It was a self-selecting group that ended up here. I think a lot of galleries that open now want to try to create the same thing, but since the program is a kind of afterthought it doesn’t really work. I feel like since you have such a consistent program, like-minded people have ended up here. It’s what people want the most but can’t figure out how to create because it just kind of happens organically, and sometimes mysteriously.

SCW: A lot of it is finding a balance between the social, the actual content of the work, and the particular relationships with the artists. If that level of social communication happens through my work with the artists and then spills into how I talk about the art with everyone else, it bridges a nice gap between the production and the reception of not just art-making but also exhibition-making.

I started this space called Elaine in Basel with three other people — Tenzing Barshee, Hannah Weinberger, and Nikola Dietrich — with whom I worked at the Museum für Gegenwartskunst Basel. There was no gathering space in the museum, no lobby or area in which we could do more public and social programming. A nice space became available next door so, while at the museum we had collection hangs and four (or more) large changing exhibitions a year, Elaine became the place for smaller, more experimental exhibitions, artist talks, performances, screenings, concerts, discos, and whatever we felt like. We would always serve drinks, sometimes food, and it was really successful at creating a social space that brought so much life to the whole program at the museum too. I think that’s what I wanted to capture again at O-Town House: that you don’t always know what you want. Depending on who shows up can be the way you figure that out, especially in a new city.

GH: As an extension of that, I feel like you show a lot of artists whose work you personally enjoy and want to see, or are friends. There’s a kind of desire that drives the program.

SCW: Once I was asked on live television in Berlin if I only show artists that I’m sexually attracted to. I was so flustered by the question that I didn’t really respond properly. But in retrospect, after thinking about that — I mean, no, that’s not the game — but at the same time there is an attraction. There are many ways to be attracted to somebody or something.

I think that being compelled by something, there’s a little flutter of “Oh, what’s that?” and you can call it sexual attraction, but it’s more than that, obviously. But I think that’s a fair thing: like, how do I decide what to do? A lot of time it is intuition, or from the gut, I suppose.

GH: And people don’t just want the newest tackiest big painting — there is a hunger for an intellectual or conceptual program in LA. But it’s not the case that you have to sacrifice “accessibility.”

SCW: LA has a deep history of conceptual art, which you don’t see a lot of being made anymore, honestly. But the roots are still here. When I worked in museums, my job was to make art accessible. The tours were sometimes three times a week, and each time I was workshopping ways of talking about the art. I think galleries have gotten used to not walking through their own shows. Most of the time there’s a press release and there’s somebody behind the desk answering emails.

But I really want to greet everybody and usher them through the show. Nothing wrong with just seeing a show and reading the press release, but I want to engage people further and have a conversation. I love that! I think these conversations are where it all happens for me.

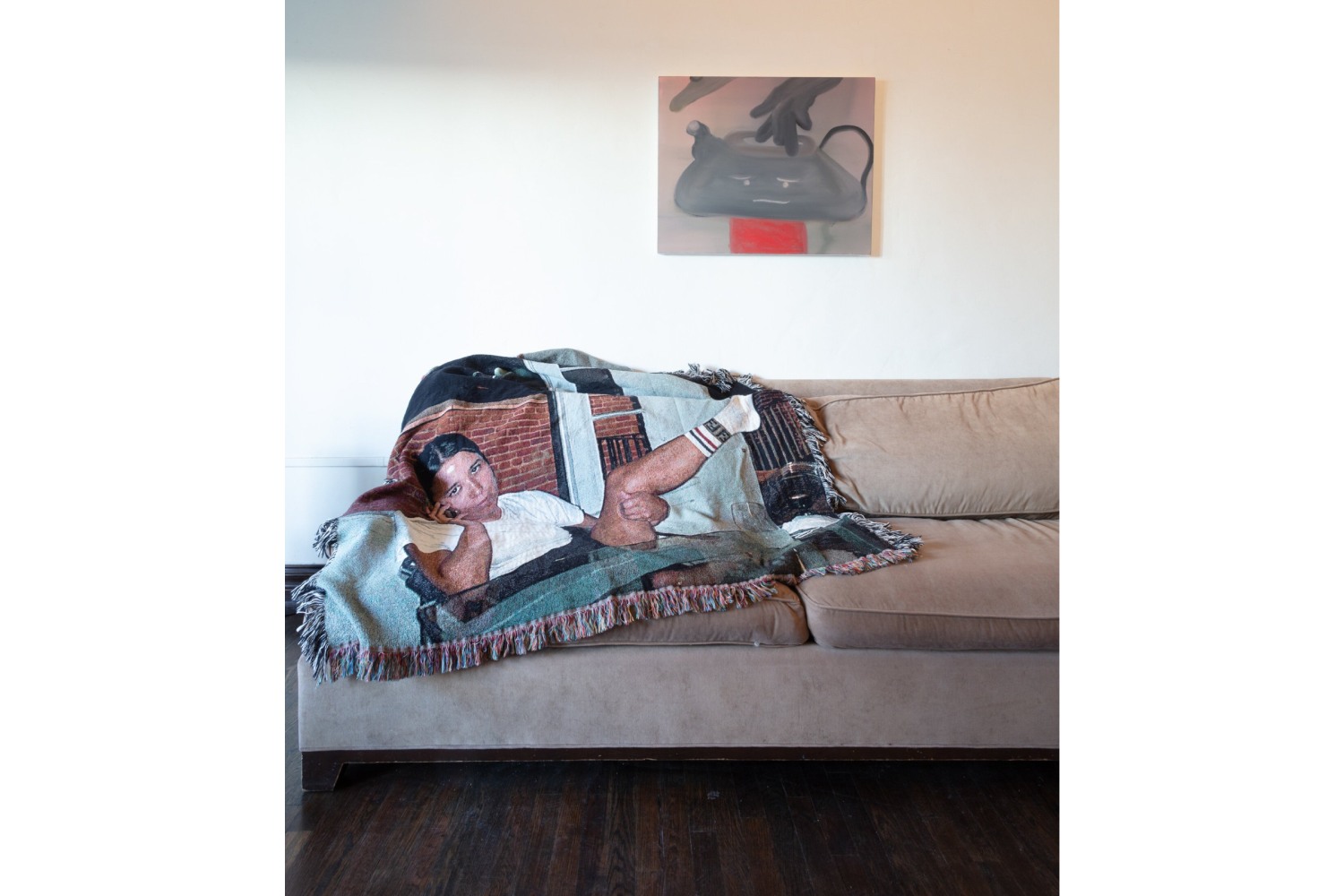

GH: I always enjoy that things tend to linger in the space, not in the way that galleries display works from past shows in the office, but that things you show become semi-permanent fixtures that you basically end up living with. Right now, for example, I’m sitting on a bench sculpture from Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff’s show and looking at the Felix Gonzalez-Torres portrait of Julie Ault around the ceiling.

SCW: Well, it’s kind of a fucked-up business model, really. It’s like: “I have a space people! Bring stuff over! I’ll take care of it!” But honestly, I love living with art. I think living in the space here is so valuable for me. That’s something that I didn’t quite realize was going to be so rewarding. Work goes up on the walls and two months later I have a very different relationship with that work. My life happens around it. Happens with it.

GH: Right, then you kind of get to know the work really well; knowing where to place it maybe? But it’s different than showing work in a fancy home as an example of where collectors might put it in their house. There’s something more intimate and active that happens, I think, for everyone who comes here.

SCW: I think the downside to having this space in this building, in terms of sales, is that it doesn’t always look quite as luxurious as it would in a big white cube. But I think it’s also important to not just see these things as luxury objects, but to regard their story and consider how they got here on the wall — how they were made and how we live with them. I very rarely sell something from above the couch.

I am encouraged by the accolades from people I really respect and admire. When mentors or legends say, “This is the best programming I’ve seen in a long time,” that really means a lot. I take that to heart, but I’m also very curious as to why it doesn’t often translate into sales. What are these collectors and institutions buying?

GH: That’s the age-old question, isn’t it?

SCW: I guess part of that is just being bad at sales and business and maintaining those kinds of relationships — is it laziness on my part? Or is it just laziness on everyone’s part?

GH: It’s like a different value system; you’re producing and championing a different kind of value, but it becomes difficult to figure out how to assert that value when we live in a world that values capital above all else.

SCW: A lot of times I feel like, “I’m gonna keep going and stick to this and eventually they’ll all come running.” But that’s also exhausting. I counted all the projects I’ve done over the past five years, which is something around thirty-eight or thirty-nine. And I was really proud of this because not a single one of those was something that I wouldn’t want to have mentioned. Not a single regret!

GH: I think it goes back to this question of integrity we discussed earlier; it just does not function as a commodity. People don’t know how to respond to or engage with it other than with admiration and appreciation or to take advantage of it.

SCW: Exactly. A good example of that is the John Boskovich show, because Boskovich is an artist who hadn’t been shown since the ’90s. He died in 2006. I started going through his storage with his cousin and we came into a wealth of stuff. I had to find my way to this work and figure out, “Who was this guy? What is his work about?” When we put on that show, I pointedly told everybody involved with the estate (and anyone who walked in the front door and asked) that it wasn’t for sale. I didn’t want a price scheme to be the only estimation of the work’s value. We first needed to restart a conversation around the work and establish its proper context within an art-historical canon. And it worked! We brought John Boskovich out of the storage facility and back into the conversation!

My insistence about not putting a price tag on the work frustrated a lot of people, and it was also — in retrospect — really dumb because I had no money. It wasn’t the plan, either, to then sell everything off at super-high prices. In the end, however, that is what ended up happening when the family decided to give everything to a gallery in New York that knew absolutely nothing about the work and just started selling it off to whomever. That was beyond frustrating. Still is. I’ll sometimes visit collectors and discover these museum-quality Boskovich works on their walls. “And we have another one at the lake house.”

GH: I think that’s really a credit to your integrity as a dealer — if you were broke, you could have just sold it and made a lot. But then you realize that if you don’t do it, someone else will.