“I feel as though I’m still not writing. I foresee and want a way of speaking that’s more fanciful, more precise, with more rapture, making spirals in the air.”

— Clarice Lispector, A Breath of Life1

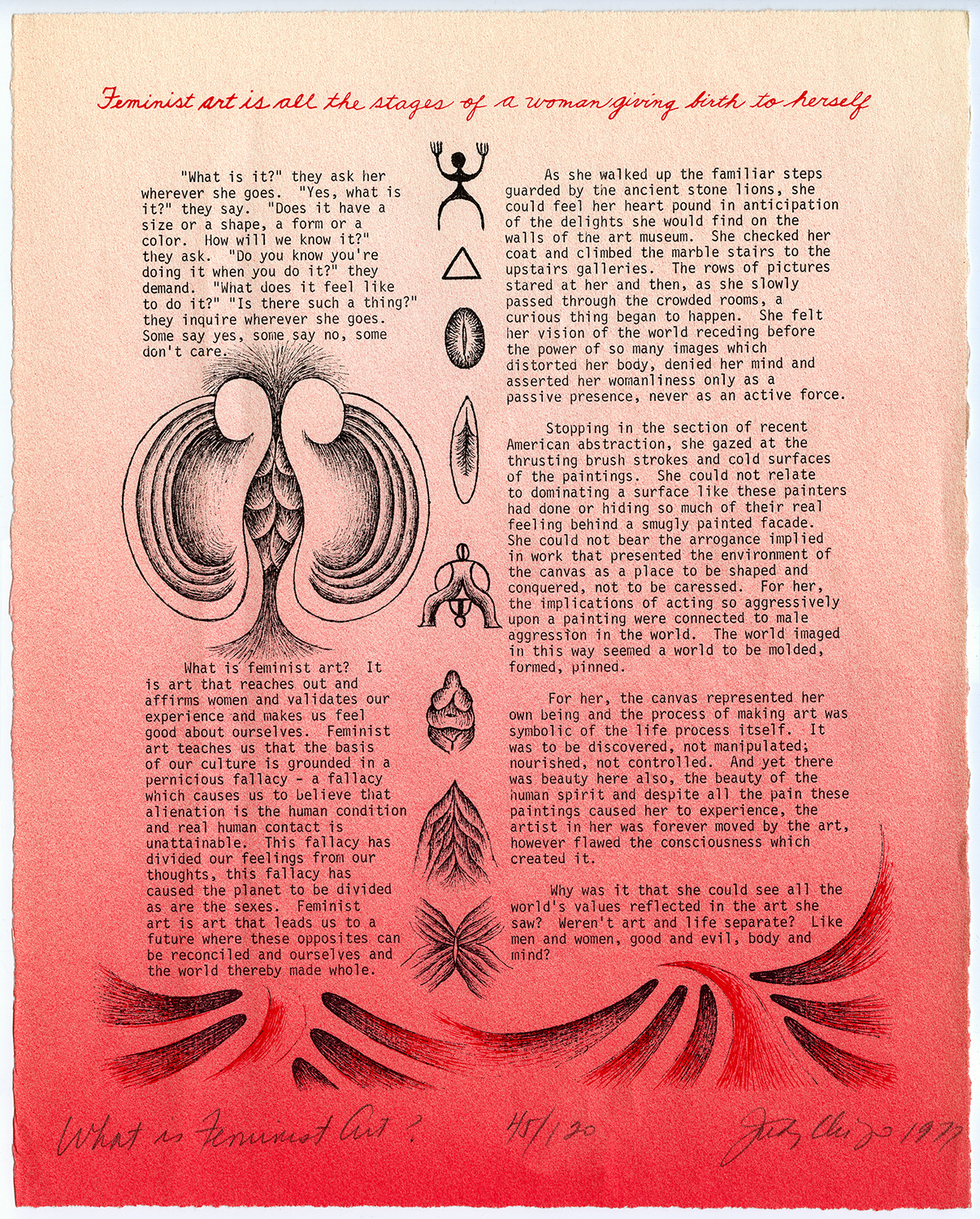

In her lithograph What is Feminist Art? (1977), Judy Chicago combines handwritten and typed text with drawn imagery under the header: “Feminist art is all the stages of a woman giving birth to herself.” Of all the myriad forms of representation on this print, my eye is drawn, as it has always been, to Chicago’s cursive title, edition number, signature, and date. The words are detailed and meticulously written, and yet they arch slightly upward — as often happens with my handwriting when I am excited and not paying adequate attention to achieving linearity. In other works combining text and image, such as Peeling Back from 1974, Chicago’s cursive words are startlingly linear, painstakingly so. Sometimes a lightly drawn set of lines guides her hand, and at other times the seamless horizontality seems entirely eyeballed.

My fetishization of markers of authorship might, in fact, be an antifeminist gesture, for it was exactly the cult of authorship that many Second Wave feminists worked against as a way of expanding the canon to those who have been denied access to myths of originality and genius. I nevertheless always wonder why Chicago’s often poetic writings have been subordinated to the imagery she pioneered, even though the two, I think, are imagined coextensively and often appear on the same visual plane. This is not merely a personal question on my part, for text often becomes the deciding factor in what is “good” feminism; it was Mary Kelly’s focus on text and the acquisition of language that caused her Post-Partum Document (1973–79) to become canonized as a more conceptual and less essentialist (and therefore “better”) iteration of feminist art. This hierarchy is especially ill-informed considering that, as Helen Molesworth has argued, Chicago foregrounds text in The Dinner Party (1974–79) by requiring that we read these marginalized women’s names.2 Insisting on legibility in a very literal sense becomes a revolutionary act. In fact, The Dinner Party was imagined alongside an illuminated manuscript that would reinterpret the Genesis story in a feminist fashion.3 Central to Chicago’s project was not only representing women, but altering the system of representation altogether to allow nonhegemonic identities to speak, to articulate themselves, to engender their own myths.

Chicago’s use of text in her paintings began with the Reincarnation Triptych (1973) and introduced a greater immediacy and legibility to the work: “I was focused on developing a clearer formal visual language and wasn’t there yet — hence the text to make my intentions clear to the audience.”4 Each of the three five-foot canvases is named after a woman who inspired Chicago, and is wrapped in forty handwritten words that offer a lyrical context to their lives and achievements. In the painting dedicated to Madame de Staël, Chicago’s text reads: “She was flamboyant, eccentric, and protected herself with a bright and showy façade.” Chicago indicated in a 1974 interview with Lucy R. Lippard that the painting “stands for me protecting myself with the reflections and transparencies and fancy techniques in my earlier work.”5 The formal language Chicago employed before developing her feminist imagery, therefore, did not signify in an adequately personal fashion; it did not allow for an affective connection to be formed between artist and viewer. In the same interview, Lippard notes in passing: “The handwriting here [in the canvas of the Reincarnation Triptych dedicated to George Sand] and in the other two paintings is an integrated formal element as well as the purveyor of added information.”6 What I would add is that the handwriting is also deeply personal and unabashedly decorative; its swirling letters are akin to the arabesques that populate the margins of diaries.

Chicago’s use of text in her paintings began with the Reincarnation Triptych (1973) and introduced a greater immediacy and legibility to the work: “I was focused on developing a clearer formal visual language and wasn’t there yet — hence the text to make my intentions clear to the audience.”4 Each of the three five-foot canvases is named after a woman who inspired Chicago, and is wrapped in forty handwritten words that offer a lyrical context to their lives and achievements. In the painting dedicated to Madame de Staël, Chicago’s text reads: “She was flamboyant, eccentric, and protected herself with a bright and showy façade.” Chicago indicated in a 1974 interview with Lucy R. Lippard that the painting “stands for me protecting myself with the reflections and transparencies and fancy techniques in my earlier work.”5 The formal language Chicago employed before developing her feminist imagery, therefore, did not signify in an adequately personal fashion; it did not allow for an affective connection to be formed between artist and viewer. In the same interview, Lippard notes in passing: “The handwriting here [in the canvas of the Reincarnation Triptych dedicated to George Sand] and in the other two paintings is an integrated formal element as well as the purveyor of added information.”6 What I would add is that the handwriting is also deeply personal and unabashedly decorative; its swirling letters are akin to the arabesques that populate the margins of diaries.

Text was, of course, a central motivating factor for conceptual artists of the 1960s and 1970s, such as John Baldessari, Allan Sekula, and Martha Rosler. Chicago, however, had none of their hyper-conceptual gloss or reluctance to reveal themselves. Even Sekula’s photo-essay centered on his family, Aerospace Folktales (1973), is deeply reticent about its status as autobiography. Conversely, Chicago’s text embraces everything that has been abjected from the (male) art object — sentimentality, intimacy, decoration, and autobiography. One is reminded of Julia Kristeva’s attempt to grapple with a semiotics of color: “There is also an ‘I’ speaking, and any number of ‘I’s’ speaking differently before the ‘same’ painting. […] We must develop, then, a second-stage naming in order to name an excess of names, a more-than-name become space and color — a painting.”7 Though Kristeva would not agree to being called a feminist, I would suggest that this naming, this more-than, is the feminine/feminist — that which cannot be normatively articulated or written without giving voice to the collective “I”.

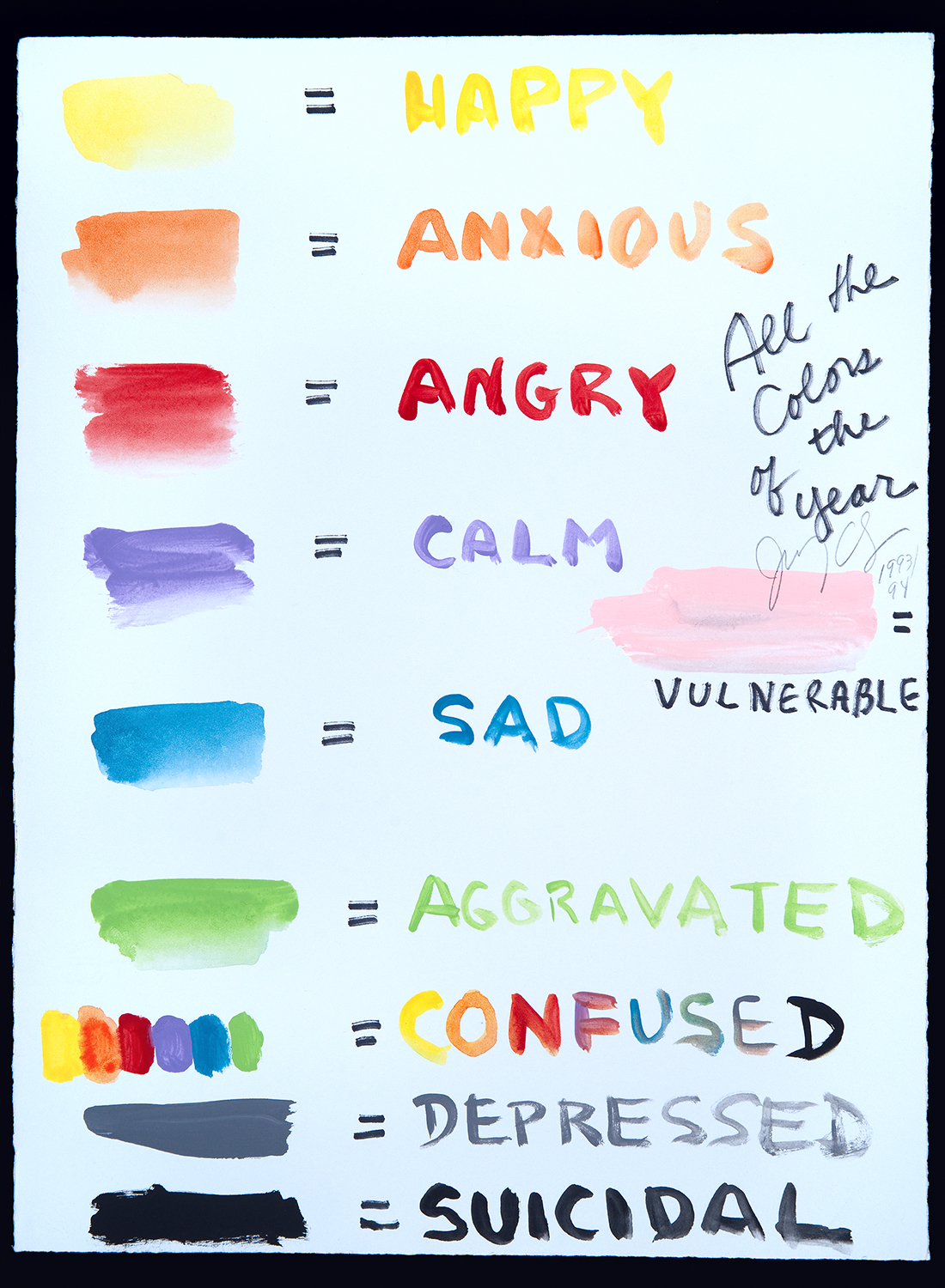

Chicago’s engagement with text reaches its height in Autobiography of a Year (1993–94), a collection of 140 drawings that chronicle a difficult year in her life. All the self-protection she described to Lippard is gone, and in its place is the bodily index of gesture: “I had spent three decades developing a myriad of techniques to mediate the gesture — spray painting, plastics, china paint, needlework, etc., and wanted to get back to it.”8 Chicago provides a color chart with corresponding emotions: yellow is happy, red is angry, and black is suicidal (we cannot help but wonder what happened on March 16, 1994, memorialized by an entirely black drawing, but of course, like Roland Barthes’s Winter Garden Photograph, we will never know). Chicago describes death and disappointment and despair with intimate detail, and what emerges is an extremely poignant visual record of depression that captures mundane and extraordinary traumas alike. It is often easy to forget the daily-ness of depression, its cyclical tedium, the way rage can transform into boredom and back again, stasis and turbulence coexisting. We might recall The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath: “I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.”9

Central to the story of text I have been sketching are three drawings from the same day (February 3, 1994) titled February already but she felt HAPPY though she’d rather be DRAWING; Instead she was using words to tell her STORY; and Her left brain was working but her right brain felt like IT WAS DEAD. In this triptych of sorts, writing becomes a reluctant savior when visual representation fails; words are both hated and revered as they provide a complicated aesthetic outlet. Does resorting to words imply, in a binary fashion, that one’s vision or visual imagination must be barren so that text can flourish? When one is already in a state of extreme sadness, such oppositions take on life-or-death importance. Other images in the series suggest that critics had insulted Chicago’s drawing skills, comparing her work to cartoons, which lends even more weight to this consideration of words. Such sexist attacks police the ground between image and text.

Unfortunately, the textuality of Autobiography of a Year provided Chicago no respite from criticism, exactly because it was not the restrained, arcane language of minimalism or conceptualism. When it was exhibited in a 2002 retrospective, it received a typically masculinist review: “Autobiography of a Year (1993–94) is a series of small, loose drawings and paintings of such domestic subjects as Woodman [Donald Woodman, Chicago’s husband and collaborator] and the artist’s cats, with notes on her feelings: ‘[H]appy sad angry’ and ‘I get anxious’ are typical of these jottings’ profundity. Another set of drawings illustrates such sayings as ‘Home sweet home’ and ‘An apple a day,’ as if to concede that Chicago’s quest for wisdom has led only to cliché.”10 This review is reminiscent of a 1979 criticism of The Dinner Party’s reliance on external narratives for its political and art-historical efficacy: “The installation needed all the documentary props and semantic legerdemain it could get.”11 These critics seem preoccupied with what a narrative should be, whose should be told and how. Chicago is lambasted whether she is seen to speak for all women or just for herself, adding to the persistent myth that marginalized groups must simultaneously occupy individualist and collectivist ideologies in order to signify to the majority.

Narrative excess, cliché, emotionality, domesticity — these derided descriptors are exactly Chicago’s point, in fact, for it is with her celebration of these feminized textual themes and devices that we might change signification altogether. As C. Namwali Serpell has argued, “While cliché connotes mindlessness, its cumulative effect is to record willfulness — the desire to share language’s materiality, to throw words at one another.”12 I wonder if Chicago balled up some failed drawings for Autobiography of a Year and tossed them in the trash. They would make a swishing noise if the toss was good, or perhaps a thud if they landed on the floor. After all, the term cliché comes from the sound nineteenth-century French printmakers would make to mimic the stereotype printing process, meaning that this semantic term has an art-historical root.13 The cliché, therefore, always sites us in the body — its movement and utterances — and all I would add to Serpell’s analysis is the fact that what she calls “the less grandiose ways we use language” are usually associated with women and queer people.14 Chicago, of course, knows this, for it is her desire to reconfigure history in both its grand, sweeping iterations and its painfully, joyfully personal iterations. It would be a cliché to say that the personal is political, but maybe in this context it is the most effective way to conclude.