Judy Chicago had been Judy Chicago for five years when she published her autobiography Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist. The artist previously known as Judy Gerowitz had made her first appearance in 1970 in the advertising pages of Artforum, wearing a bandana, close-cropped brown hair, and an insolently perched pair of round sunglasses. A month after this media breakthrough she was in Artforum again, this time triumphantly sporting her new name on a white sweatshirt in a boxing ring. Thus she gave birth to a character who was initially just a figment but whose power of self-assertion was already having an impact.

Her political commitment might have been explicitly radical, but Chicago chose to pursue it via her own milieu — the art world. Her participation in the group show “Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors” at the Jewish Museum in 1966 had earned her a reputation as a Minimalist, a label that meant she could promote her portrait of the young artist as feminist to a specific end: to challenge her peers and colleagues. Her way of doing this was to appropriate the codes of Pop art and repurpose them, while maintaining the Minimalist/Conceptualist anticapitalist critique of the Pop ethos. The badass portrait she invented was intended as a break with the cool image of a mass-media icon. At the same time, the art magazine as such was exploited as a medium in its most obvious commercial aspects — especially in the age of art’s dematerialization — and thus subverted and occupied.

In fact this new persona followed in the wake of the macha, the feminine macho persona Chicago had deliberately adopted during the 1960s as a way of getting the recognition of her peers, the so-called “studs” who formed a community around Los Angeles’s Ferus Gallery.

At the junction of the critique of the art object and new social paradigms, Judy Chicago was born.

Sexual Phenomenology and the Dematerialization of Art

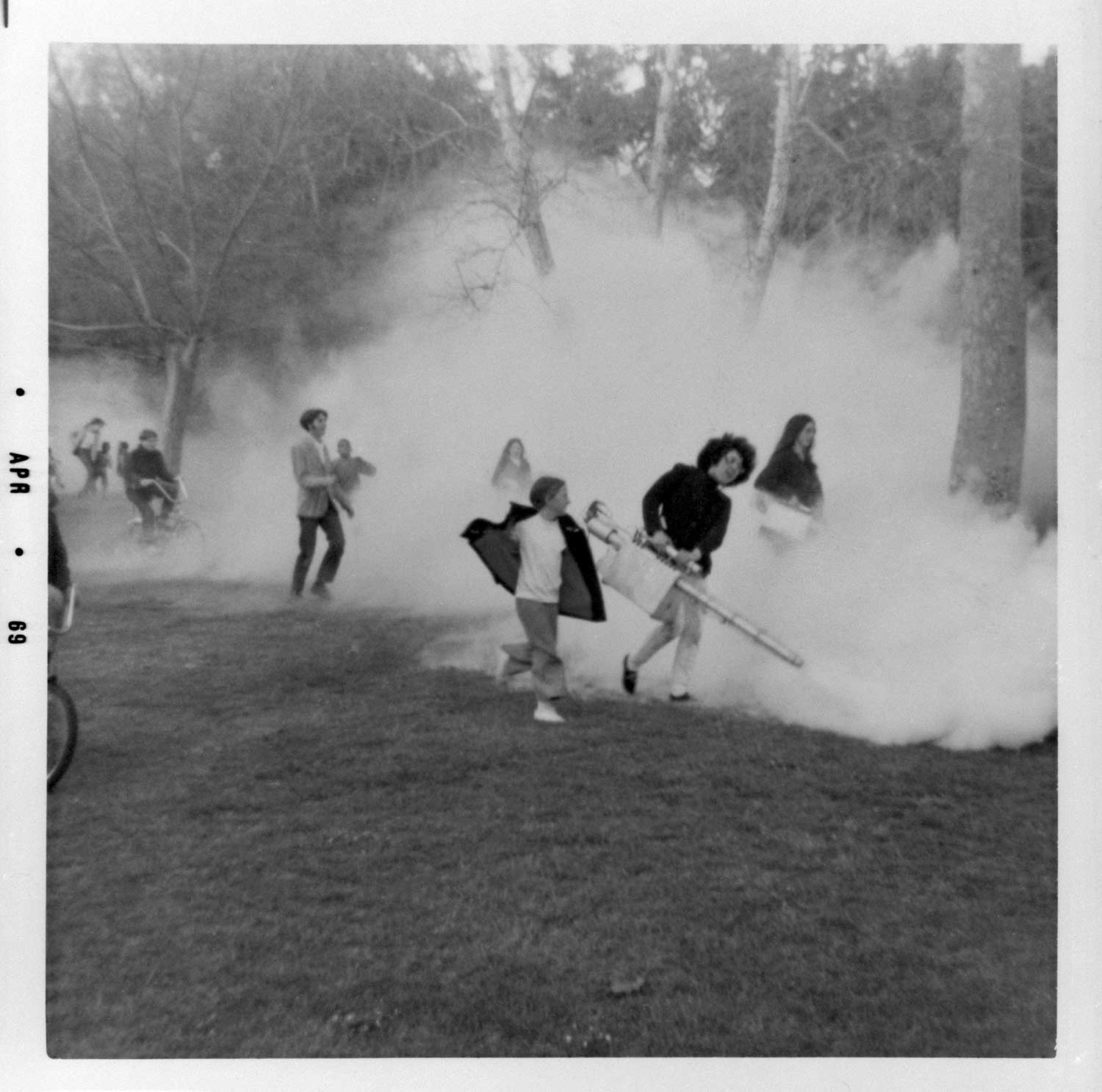

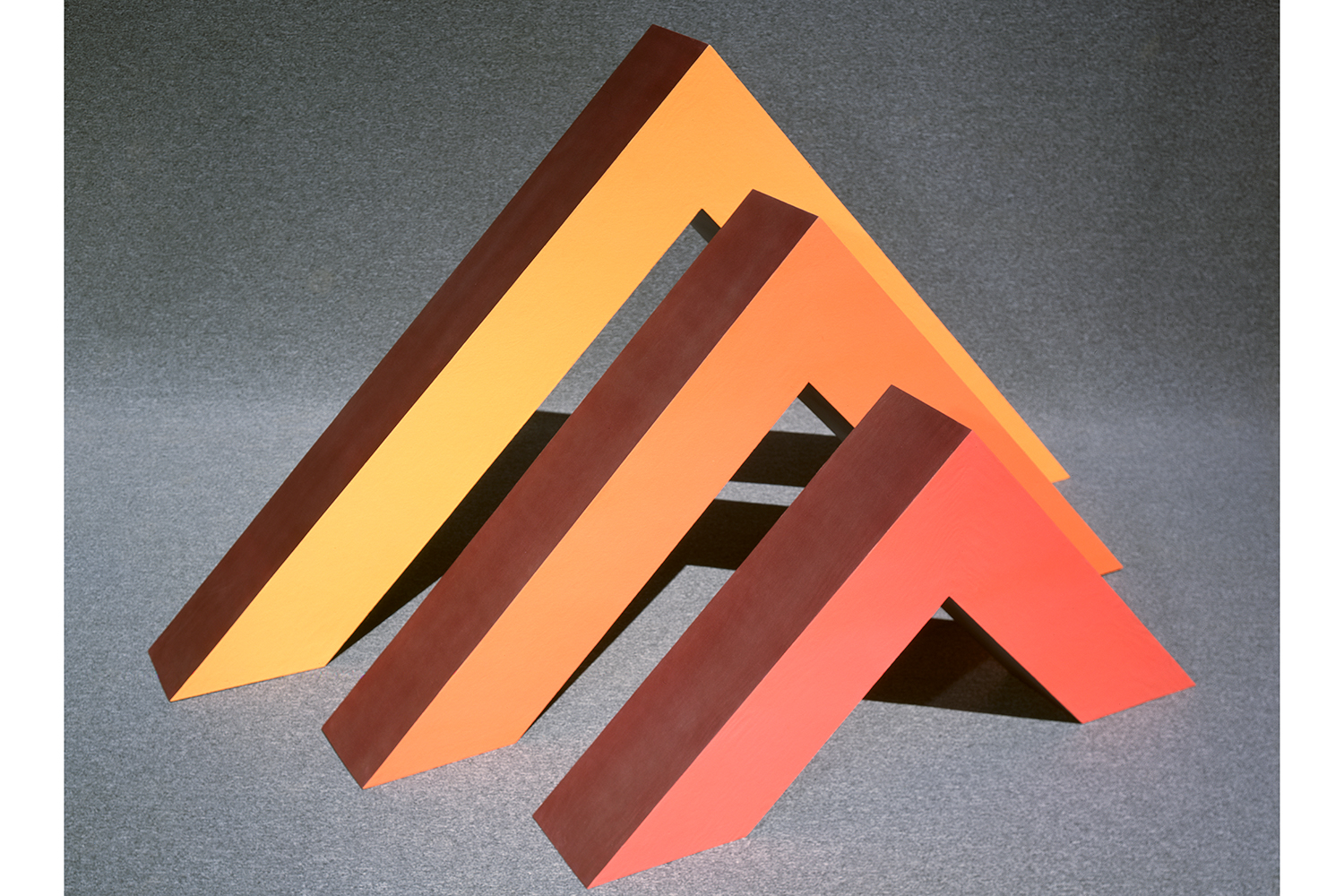

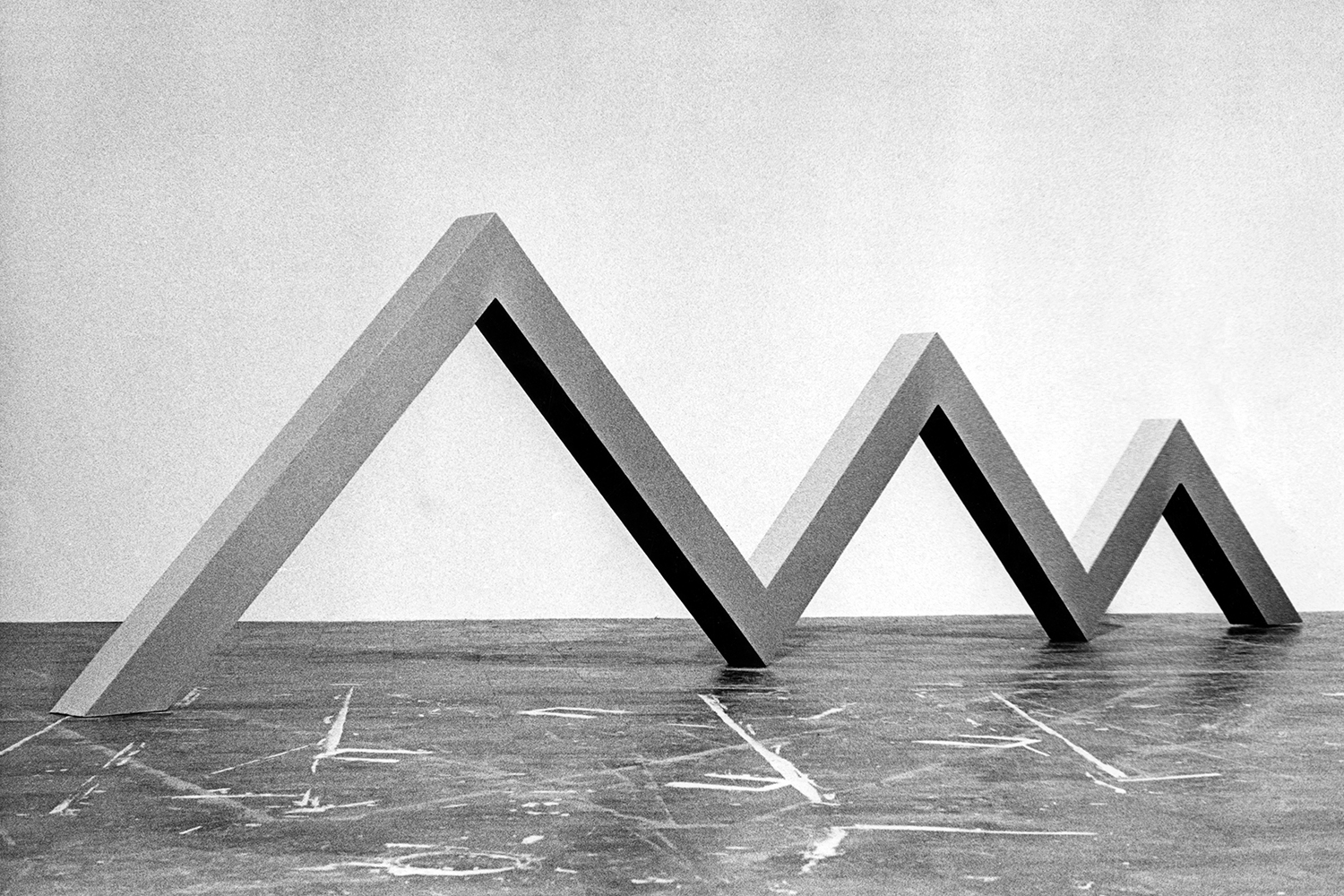

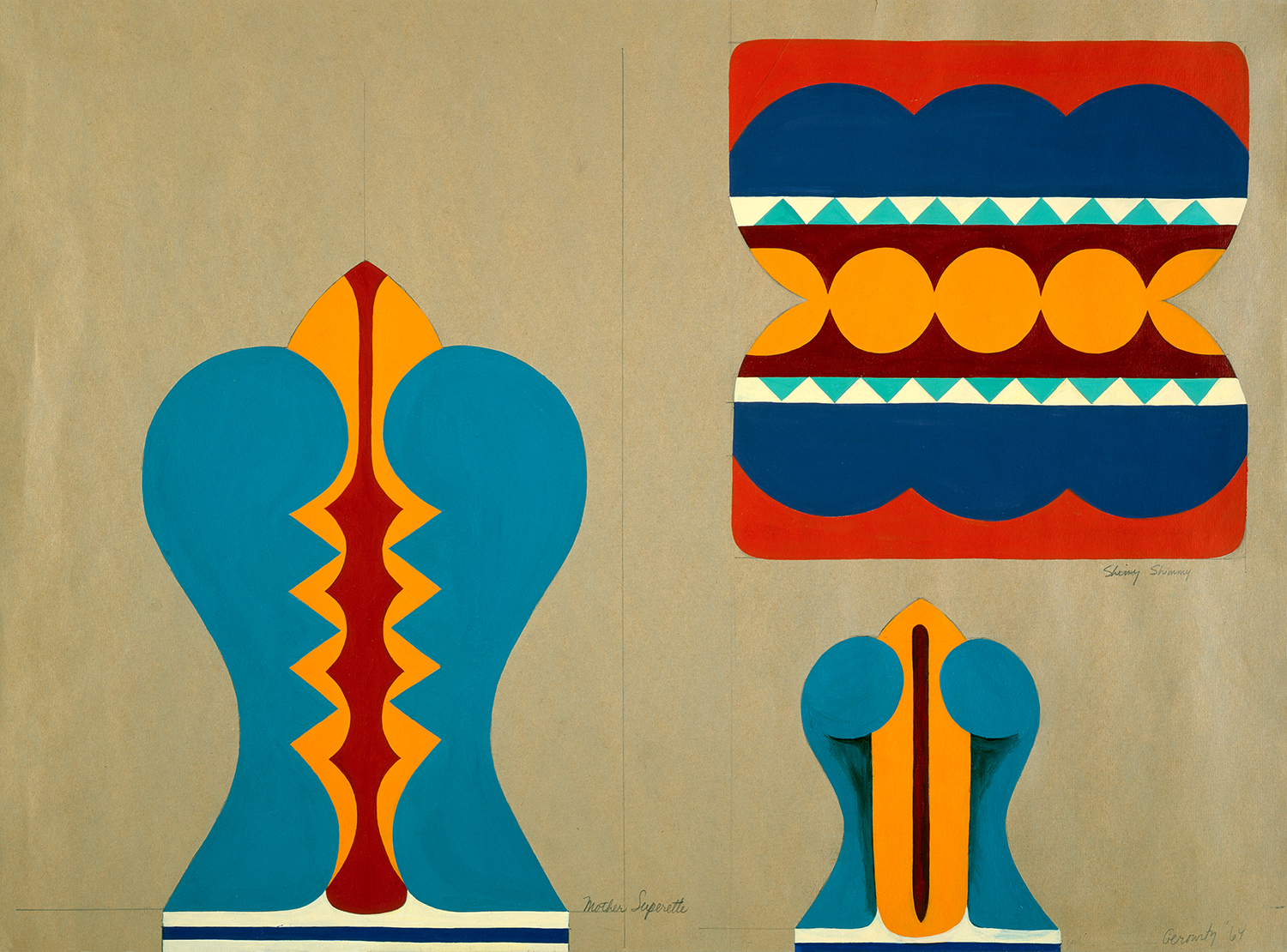

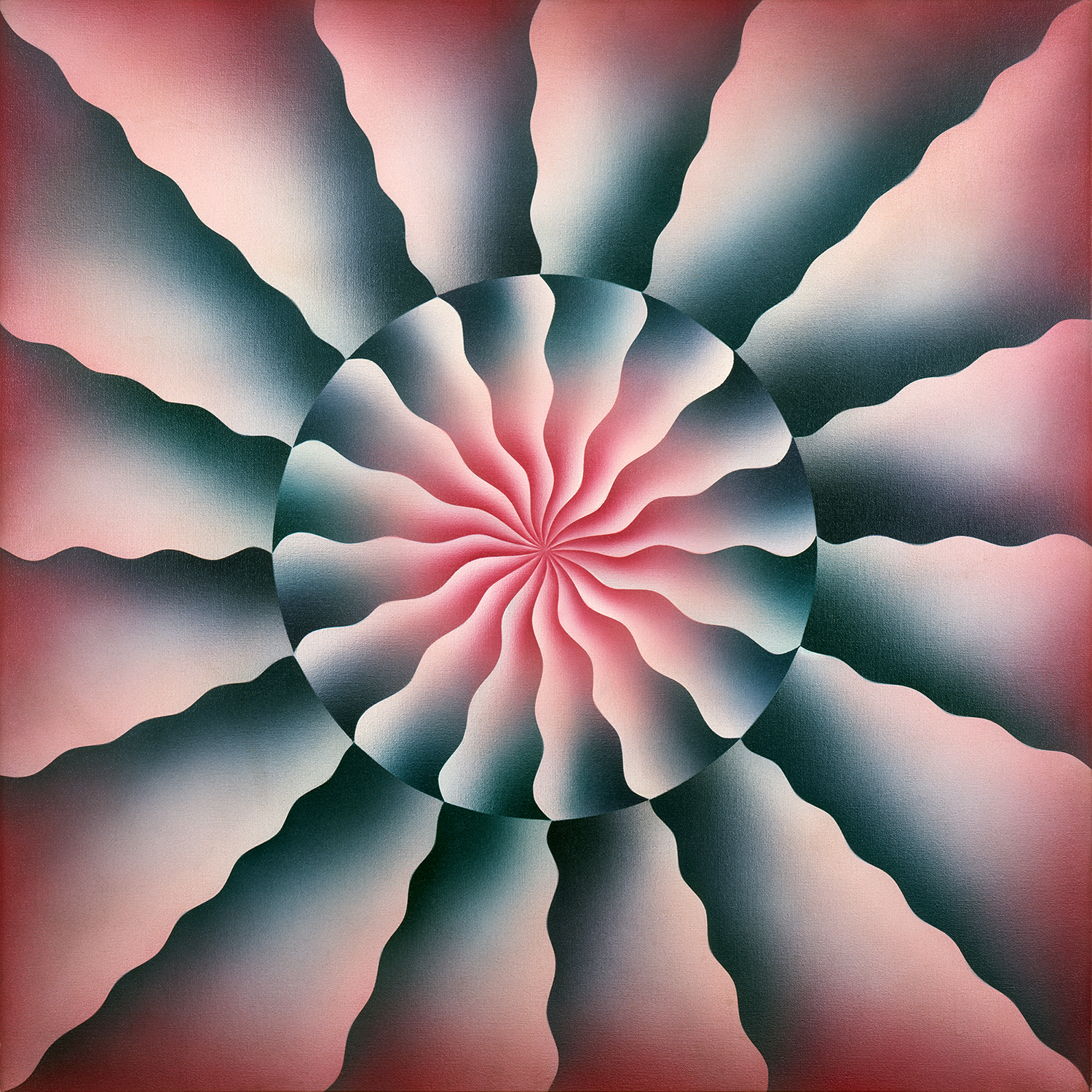

The tactical and narrative transition from Gerowitz to Chicago took place at the same time as her first solo exhibition, at California State University, Fullerton. In addition to the Artforum ads, the show included works from the “Atmospheres” series (1968–), pyrotechnic performances celebrating the multiorgasmic power of the goddess figure. Curves symbolizing political fertility were part of the “Domes” series (1965–) — small, glossy, pastel-colored objects of expanded polyurethane — and their painterly transposition, the “Pasadena Lifesavers” (1969). Eight years after her early attempts with Mother Superette (1963), this series of paintings inaugurated the chromatic experiments of the “central core imagery” she had initially spotted and analyzed in the work of Lee Bontecou, Emily Carr, Jay DeFeo, Barbara Hepworth, Louise Nevelson, Georgia O’Keeffe, Deborah Remington, and Miriam Schapiro.

This vaginal evocation was born of an urge to share. Central core imagery became the principal vector of a revolution that was not feminine (a nuance that received a mixed reception from British Constructivist feminists) but sexual: for and by women. Writing about the “Pasadena Lifesavers” with regard to this revolution, Chicago said, “They embodied all the work I had been doing in the past year, reflecting the range of my own sexuality and identity.”1 As she saw it, emancipation from a patriarchal tradition would take place through the achievement of a fullness of enjoyment — in the dual sense of hedonistic pleasure and usufruct — that correlates with the development of one’s artistic maturity.

She found the justification for writing her autobiography in the erotic diaries of Anaïs Nin. The initiatory quest of Through the Flower follows Nin stylistically, but takes on a more personal cast when the author describes her gut interest in another — visual rather than literary — erotic culture: “I was interested in dissolving sensation, like one experiences in orgasm.”2

This entirely new undertaking consisted of a critical sublimation of the strategy of pornography. Sexuality is bluntly proclaimed — this is “cunt art” — while remaining pictorially oblique. This subtlety was misapprehended by the inheritors of a Lacanianism unsympathetic to any notion of polymorphous pleasure. Moreover, the Marxist feminists Mary Kelly and Griselda Pollock failed to take into account Chicago’s role in the dematerialization of art on the West Coast. This excessively literalist riposte on the part of these feminists misses the point: the auratic image of an intense sensation that is dematerializing.

Chicago is fully aware of the importance of sex as a political object, and of the need to transcend purely artistic goals. The badass persona’s I becomes an active force for us.

Knowledge and Pleasure

As soon as it appeared in translation in 1954, Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex met with resounding success on America’s campuses. The French philosopher’s rallying cry resonated with the new transatlantic aspirations: being a woman is a given of one’s history, not an explanation. The aim here was not so much to ensure the liberation of woman as to trigger collective thinking about women as a historical category. However, the development of this new knowledge could not happen without consideration of another given: pleasure. Aimed at shaking off moral and religious control of social mores, the first demands of the women’s liberation movement focused on free access to contraception and abortion, which immediately paved the way for unprecedented experimentation relating to the body. In this context building up an archive made possible the historical deconstruction of the privileges governing pleasure and the unrestricted imagining of a brighter future. United under the Women’s Liberation banner, the “people without a past” of the French feminist anthem realized they had set the stage for a new era of revolution.

Marked by this paradigmatic shift, Chicago’s break with her previous work eluded art critics, who in spite of everything continued to see it as part of the L.A. Finish Fetish movement. Thoroughly aware of the yawning gap between her artistic ambitions and its public reception, she came up with a project for a community devoted to the emergence of a new visual culture: the first year of a new way of seeing could only be instigated collectively. Thus was Womanhouse (1971–72) created, followed by the Woman’s Building (1973–91). Womanhouse’s opening exhibition and subsequent performances entered the art canon, but insufficient attention has been paid to the important archival work put in by the history-makers involved. Members of the Womanhouse community — in many cases artists or students — dug deep, delving into old files, libraries, and secondhand bookshops in search of a buried past, bringing their findings together in a database that would become the source for anthologies to come and would later form the structure of an education program for a public audience. Thanks to Chicago’s visionary capacity, this new history of art was complemented by a skills cooperative, an indispensable factor in ensuring independent distribution. The fertile compost of radical teaching would activate the different stages of this cultural revolution.

Chicago’s commitment to historiography, the driving force behind the shaping of a herstory that was a particularly rich source of collaborative impetus, changed her approach to painting. Her series “The Great Lady” (1972–73), a new, hypnotic variation on cunt art, included a mass of handwritten notes. This stage completed, she left the Woman’s Building and its host of activities to devote herself to the creation of a monumental history of pleasure by and for women: The Dinner Party (1974–79), a work confronting the ongoing erasure of women’s contributions to culture.