In this exclusive interview for Flash Art, cult moviemaker John Waters spoke to artist Mike Kelley about a range of topics including the aesthetics of DIY practice, folk culture, and their memories of high school. The talk was recorded in September 2005, in anticipation of Day Is Done (Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions #2–32), Kelley’s multipart installation presented at Gagosian Gallery in New York later that year.

John Waters: I had a tooth pulled at seven this morning and I was thinking about your work on laughing gas. What’s the title?

Mike Kelley: Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction.

JW: That will never fit on a marquee in a mall, Mike! [laughs] I know that a lot of artists today want to make movies, but this isn’t a movie, this is a true epic! Warhol made Four Stars (1967), a movie that lasted twenty-four hours. Is this your Four Stars?

MK: It’s eventually going to consist of 365 parts, so it’s supposed to last almost a year.

JW: I’ve seen the videos that you sent me, but what is the entire piece going to be when it’s actually all together?

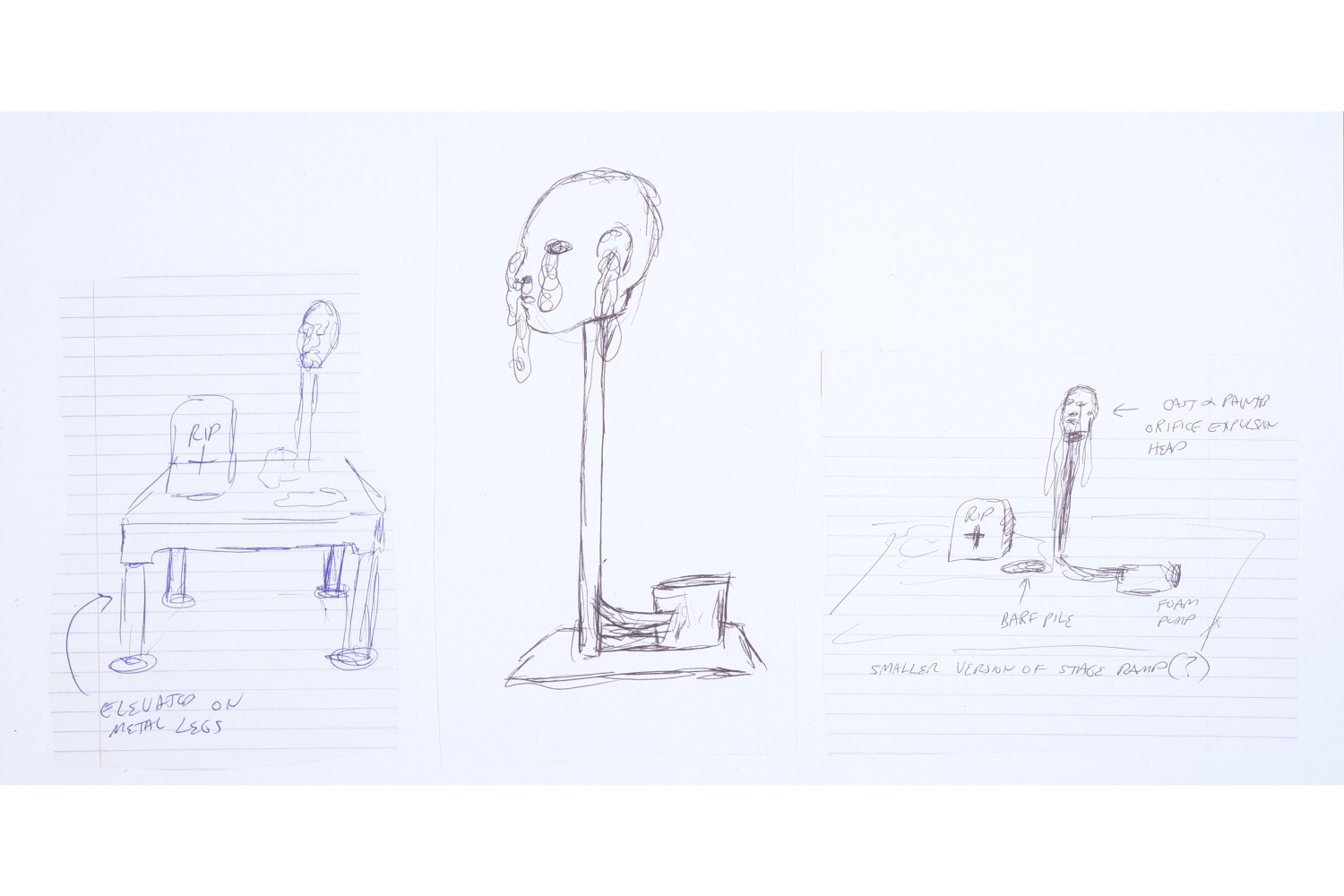

MK: I’m going to show it at the Gagosian Gallery in New York. I’m taking all the walls out, so it will be one big open space with about twenty different stations. Because some of the stations contain multiple tapes (there are over thirty tapes in all) the whole ensemble will need to be computer synched. Imagine you’re in a warehouse where stage sets are stored and videos are programmed to play in each of them; that’s what it will be like.

JW: Stations meaning the Stations of the Cross?

MK: Like that, but I was thinking more of the product pavilions at a state fair, where one can roam from booth to booth.

JW: You’ll have showtimes?

MK: No, but three video sequences will run simultaneously, spaced so that the viewer can catch most of the action without spending all day at the gallery.

JW: To see the entire thing, how long would it take?

MK: Three hours.

JW: No matter what any film director will tell you, whenever they see art videos, their heart secretly sinks. But this is not just a movie… this is an environment that includes three-dimensional artworks.

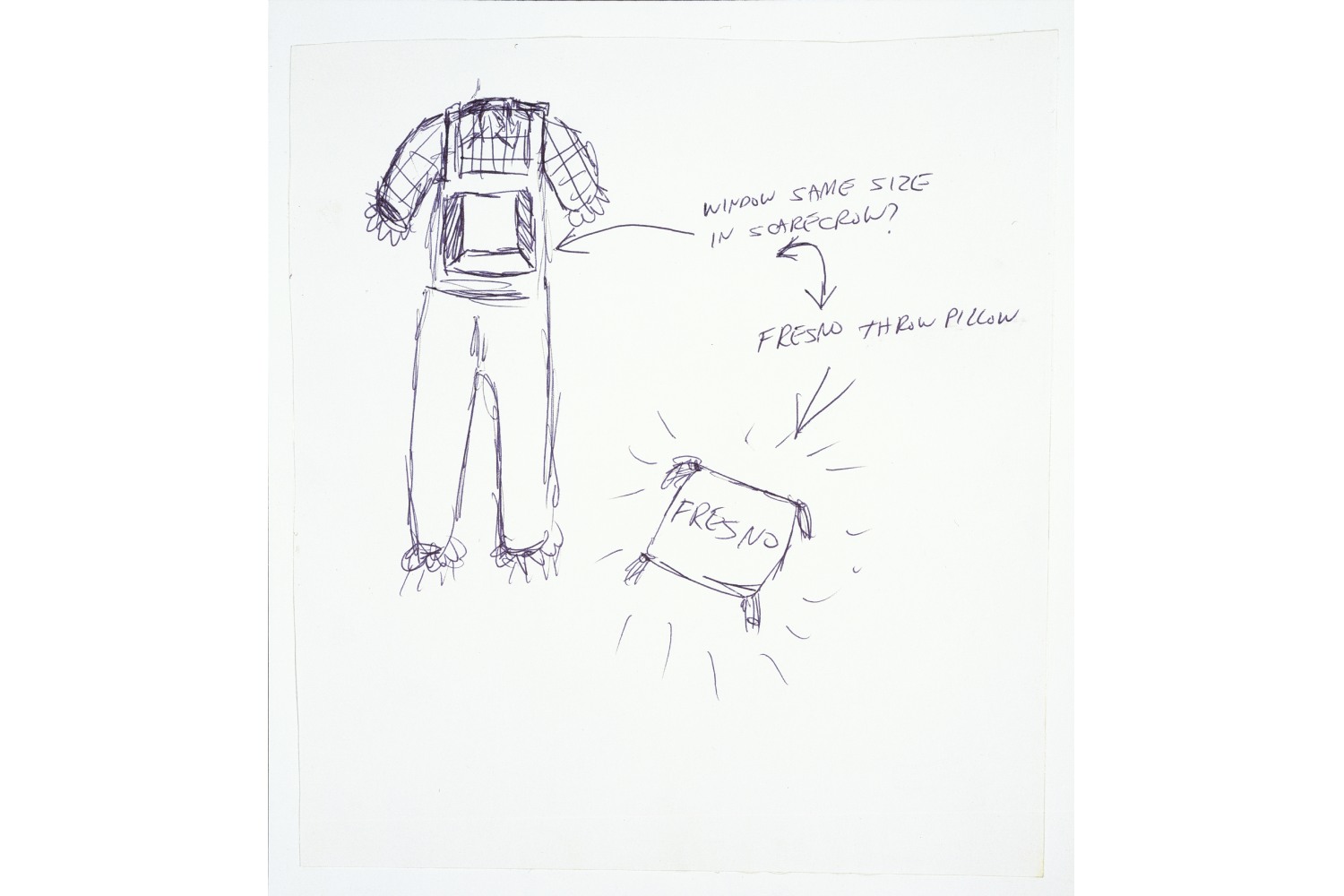

MK: I consider the sets themselves to be sculptures. And I’ve made other sculptures, related to various scenes, out of props. I’m tearing up some of the costumes and making soft sculptures out of them. For example, there is a scene that features three office coworkers, one of which is a vampire. I ripped all their clothes up and made a kind of stuffed multipart blob: one character out of three.

JW: So, new artworks are made from the movie props. When did you start on the project?

MK: Most of it was done in the last year, but the writing goes back about another year.

JW: Do you ever reveal the budget? It certainly has the production values of a big-budget independent film.

MK: Perhaps more like a TV movie.

JW: I love that you wanted to tape it like early TV.

MK: When I was working on Day Is Done I looked at a lot of variety shows from the ’50s and ’60s, like “The Lawrence Welk Show” and the “Red Skelton” and “Milton Berle” shows. I was interested in how they were shot and the kinds of variety entertainments that were on them. We shot Day Is Done like they used to shoot sitcoms — basically live with three cameras.

JW: How much is “we”?

MK: Well, I had an assistant director, a director of photography, two other camera people, a couple of sound people: a small video crew.

JW: All taped in Los Angeles?

MK: Yes.

JW: In one location?

MK: No, all of the shots on sets were taped in my own studio, but there were a few locations such as a gymnasium and CalArts, which I rented when it was empty in the summer. All of the corporate-looking scenes were shot at CalArts: the office interiors and hallways. And all of the woodland scenes were shot in a park near my home.

JW: You said that you were thinking of doing an art gallery version and a theatrical version. What is the theatrical version?

MK: It would be the same material but with more crosscutting between scenes.

JW: But not like Chelsea Girls (1966), with two scenes that play at once next to each other?

MK: In the gallery installation I do things like that; I’m not sure if I would do that in the single-channel version.

JW: You said you were trying to be “grandiose.” What did you mean by that?

MK: I meant that I think of the project as a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, a total artwork in the Wagnerian manner. But then, Hollywood films are that: mixtures of writing, dance, theater, music… I’m attempting to make a feature film spread out in space.

JW: All this seems to come from the work you did where you reconstructed all of the schools you have ever attended (Educational Complex, 1995). The parts you couldn’t remember were left blank. It’s a lot about recovered memory, correct?

MK: Exactly. Then, five years ago, I did the first video in the series: A Domestic Scene (2000).

JW: Do you believe in “memory recovery”?

MK: I have grave misgivings. And I know that there have been horrible miscarriages of justice using this theory as an excuse.

JW: Nobody ever recovers good memories. “Oh, I remember when my parents were really nice to me, and I’d forgotten!”

MK: The whole idea strikes me as simply an inversion of the family romance.

JW: Is this why you talk of “mimicking victim culture”?

MK: Yes, it’s the idea that all motivation is related to repressed trauma. I took that as my starting point. Reality is not interesting enough, so load it with repressed trauma. But then all of my “recovered memories” are of the blandest forms of folk entertainment: normal culture, which, perhaps, is itself trauma!

JW: What kind of student were you?

MK: …freakish.

JW: Did you do extracurricular activities? I did none. I am the only one where under my yearbook picture it says nothing after my name.

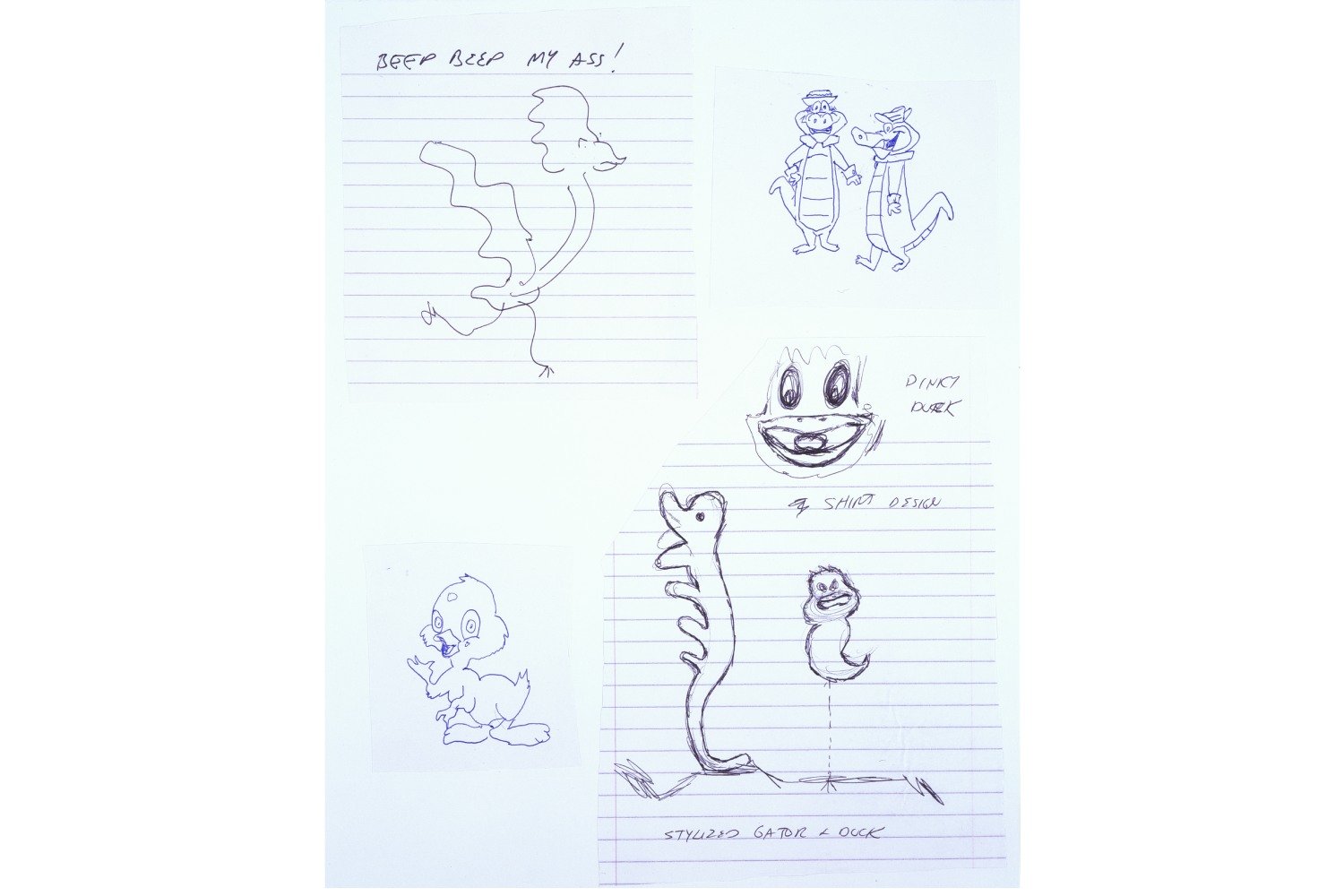

MK: I had nothing to do with any of that club or sports stuff. I didn’t even go to graduation! But this piece isn’t about high school. It’s about common cultural rituals. Yearbooks were just a convenient place to find pictures of these kinds of activities. I’m talking about really base carnivalesque activities like “dress-up day” at the bank or office… “Jeans Friday.”

JW: I don’t think they did that when I was in high school.

MK: When I was a kid, you’d go into the bank on Friday, and it would be “Gay Nineties Day.”

JW: I remember once I went inside the bank and they all were wearing full Halloween costumes. How do you hand your hard-earned money to someone dressed as a goblin at eleven in the morning?!

MK: [laughs] It’s so pathetic to see workers allowed such phony “freedoms.”

JW: There are so many different chapters in this work. What is the finale? Is it the “Hag Mary” scene? That is one of my favorite parts: the “fascism” of Mary; the “revenge” of Mary.

MK: That was my attempt to mimic the look of Dario Argento’s horror films. But no, that’s not the finale.

JW: And then there’s the barbershop scene. That really speaks to me. I was sentenced to the barbershop by my school. They would force me to go there. I had the horror of going to the barbershop. They always had the worst magazines, like Field & Stream.

MK: A barbershop is really a man’s place. Going there, as a boy, is a rite of passage. The men always demean you; it’s just horrific! Going to the barbershop, for me, was like going to confession. I think I went twice and then I said to myself, “I’ll never do this again!”

JW: There is even nostalgia for barbershops in New York now! [laughs] How long did it take you to shoot all of this? How many shooting days?

MK: Something like fifteen days. We would generally shoot two or three scenes in a day. It was very tightly scheduled.

JW: And who is the cast? Is it friends, students, art people?

MK: No, I put ads in the professional papers; they are real actors. The big problem was that the actors had to look like the people in the found photographs, which was very limiting.

JW: Has working on this project made you want to make a traditional feature movie?

MK: Not a traditional one, but I’d like to make a feature film. In fact, I’d like to transfer the single-channel version of Day Is Done to 35mm film and submit it to festivals like Sundance.

JW: Certainly, it’s worth a try. I have been on many juries and it isn’t like anything else I’ve ever seen! You know, I love how you used canned laughter.

MK: I used canned laughter, mixed with heavy “emotional” filmic music, in the “Singles’ Mixer” scene. It’s designed to be contradictory.

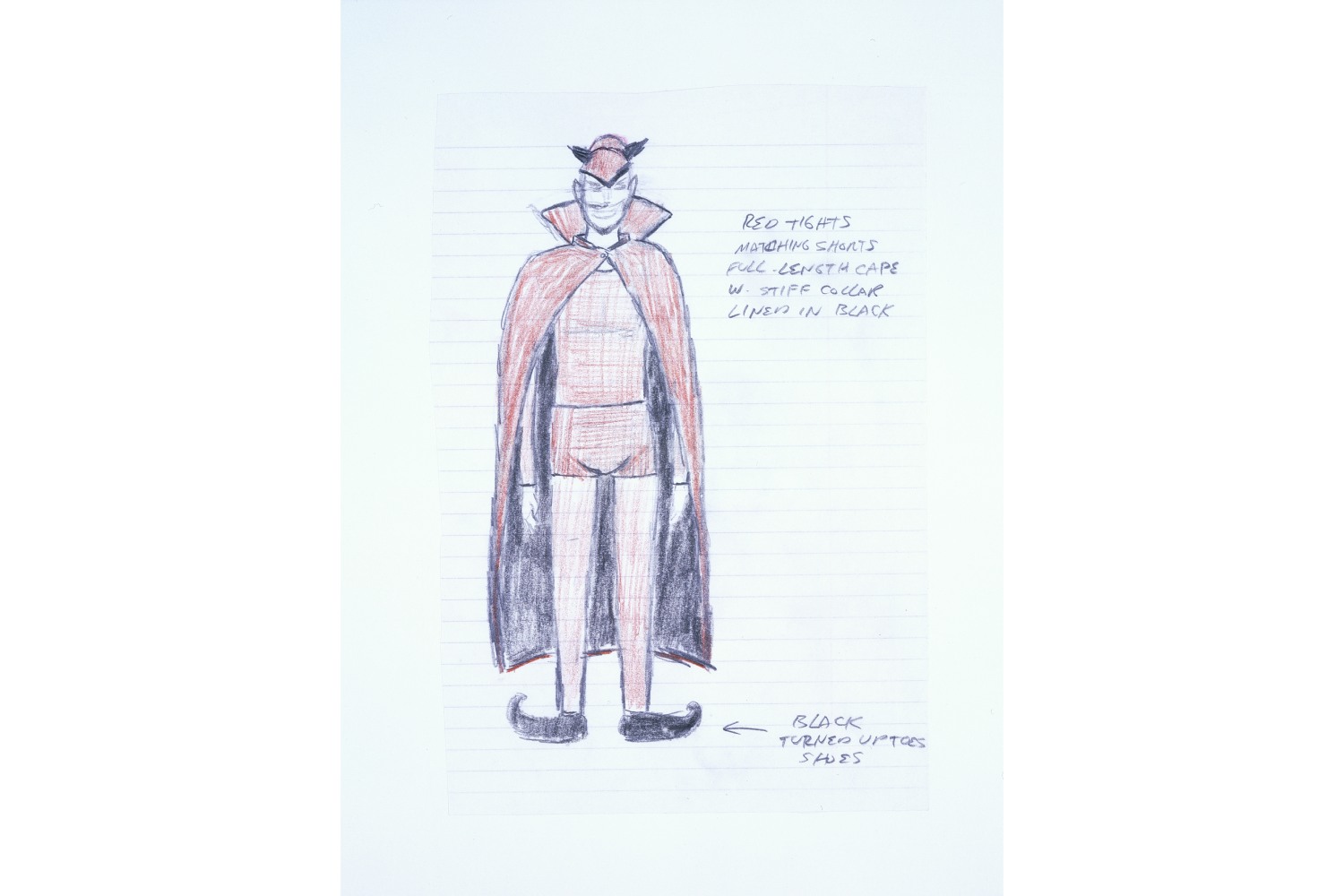

JW: You sent me a list of seven subjects that the tapes are based on, like religious performances, thugs, dance numbers, hicks and hillbillies, Halloween and gothic style, satanic imagery, and equestrian events. All of these subjects are found in every yearbook. I’m doing a piece right now about teachers who wrote mean things in my yearbook, like, “to someone who can but doesn’t.”

MK: That’s really good!

JW: I had a worse situation that was really torture: I had bleached hair in junior high, which no one else did. I got my school pictures back and, anonymously, someone had put in a little note that said “the camera doesn’t lie,” which meant, “Hi faggot.”

MK: That’s terrible! I refused to let my picture be taken in high school so I’m not in the yearbooks.

JW: Among the seven categories you list are religious performances. Did you have that in school?

MK: Yes, I went to a Catholic elementary school.

JW: Were you in pageants?

MK: I was in a May Crowning ceremony once. I think I was picked because I was the smallest boy in class. The “May Crowning/Hag Mary” videotape comes out of that experience.

JW: Oh, god! Did you use your pictures of it?

MK: No. I don’t have any pictures of it. But I did an image search on Google for May Crowning and thousands of pictures came up. May Crownings are still being performed… it’s so pagan!

JW: And thugs, everybody had thugs in school. I liked them. Thugs weren’t ever in any of these extracurricular activities. Were you a thug?

MK: No, I wasn’t a thug. But I knew them; I didn’t want to get beaten up.

JW: I was a thug hag! [laughs] And there’re musical numbers in the tapes.

MK: Yes, some of this project developed out of a version of the musical Li’l Abner rewritten in the style of H. P. Lovecraft that I had been working on. I consider Day Is Done to be a musical.

JW: Did you write the music?

MK: Yes, all of the lyrics; and the music in collaboration with a musician named Scott Benzel.

JW: Talented! You’ve got to come to Broadway!

MK: Broadway is my dream.

JW: Now, Halloween of course was a big deal. I hate Halloween, but I loved it as a kid.

MK: Oh, it’s always been my favorite holiday; it’s close to my birthday. Birth day/death day… right together. But I’m from Detroit where Halloween is a religion.

JW: Well, that’s where they celebrate Devil’s Night, the night before Halloween; it’s more than a religion.

MK: On Devil’s Night you’re supposed to go out and vandalize. After the Detroit riots in ’67, people would set the inner city on fire every Devil’s Night as a kind of anniversary.

JW: You were supposed to do that as a kid, right?

MK: Minor vandalism, yes. I think it’s really just a nostalgic looking back to rural pranks, like tipping the outhouse over. But it got out of hand.

JW: When you were in high school the satanic movement wasn’t that big, was it?

MK: That really developed in the 1970s. I was an adult already. I found it silly.

JW: But you, visually, have a lot of that in your work.

MK: I think it’s because it’s such a common cultural myth. Satanic and UFO conspiracy theories are two of the dominant cultural myths of the moment.

JW: The other thing that I enjoyed in your tape is the “equestrian event.”

MK: It’s a horse costume dance that’s supposed to lead up to a donkey basketball game.

JW: What’s that?

MK: It’s an inversion-of-roles event where students and teachers play basketball while riding donkeys, which is impossible to do. It’s purposely ridiculous: the donkeys just crap on the floor, and the players fall off of them. Sometimes the players are in drag. It was very common in schools when I was a kid. I even went to one in Los Angeles in the early 1980s.

JW: God… I’ve never heard of that one!

MK: There would always be a guy dressed as a clown with a scoop to pick up the crap. That was the big joke. It’s really the most pointless event ever: that’s my grand final spectacle. I’m going to shoot it at the end of the entire series.

JW: What about the Virgin Mary scene?

MK: I think that is the scene that will cause the most people to cringe. The “Picking a Mary” contest scene is a mixture of the TV show “What Not to Wear,” which is a fashion makeover show, and a scene that focuses on a girl’s poise class from Frederick Wiseman’s documentary High School (1968).

JW: I thought it was between a cute Miss America and the Virgin Mary: a beauty pageant and a religious pageant. Is there fashion criticism?

MK: All of the fashion critique is patterned after the advice given on “What Not to Wear,” which I think is a disgusting show because they take persons who have very individual street style and make them over to look like Manhattan boutique salespeople.

JW: Your contest is a religious version of that. There is even a supplicating Joseph. It seems to be the male humiliation version of the story.

MK: I found that long self-deprecating speech by Joseph in the Apocrypha. I didn’t write any of it! It is so incredibly masochistic.

JW: Basically Joseph is pussy whipped?

MK: Completely pussy whipped! It’s obvious that he and Mary are never going to have sex!

JW: Or she doesn’t remember, which is worse! [laughs] So, after this scene there’s the May Crowning ceremony.

MK: Yes, Mary is picked, and then she is crowned. That’s the public display of the new Mary.

JW: And you also have a Shadow Dance and a Gospel Dance.

MK: The Gospel Dance is one of three premarital entertainments presented for Mary’s amusement. The Shadow Dance is the erotic dance; it’s designed to be a kind of “marital aid” for Mary. The third entertainment is the Nativity Play. The little girl in it is Jim Shaw and Marnie Weber’s daughter, Colette. She danced to some children’s music, which I cut out and replaced with electronic music. It doesn’t fit at all. That kind of friction interests me. The work is very much about deciding when to adhere to these folk forms and when to deviate from them. I like to push them toward either more overtly ritualistic practices or modernist avant-garde conventions. I like to make them “artsy” in a very mean way.

JW: Did you go to any real school pageants while you were shooting?

MK: No. But I went to a children’s version of Li’l Abner sponsored by a church. I found it very inspiring.

JW: I was invited to a school for mentally challenged children that redid the musical Hairspray. I couldn’t go for legal reasons, but I always thought it could have been the best production of the play.

MK: Next door to me is a home for juvenile delinquents. They’re incredible thugs. I would love to do some kind of theatrical production with them; something they have no interest in. It doesn’t matter what it is. I’m just interested in capturing their disdain. I’d like to work with untrained people who represent different types of institutional environments.

JW: There’s usually an ad in the director’s guild trade paper that says, “imagine what it would be like if you didn’t have professional actors and different parts.” It might work in some ways, but in some ways it can be terrible. A lot of people in real life have amazing personalities, but when you turn a camera on them, they can’t even play themselves.

MK: I know, but on the other hand there are directors who are masters at using non-trained actors, like Pasolini or Fellini. Or Warhol, he certainly knew how to pick people.

JW: He knew he picked the right ones. Fellini would just put words in their mouths in massive post-production work. What about the post-production and the soundtrack of your work?

MK: Most of the dialogue, music, and sound were inserted after the editing. The shoots were nothing compared to the post-production process.

JW: It’s a huge project. You’ve made an epic.

MK: That could be a problem: this whole thing could just be one enormous vanity project.

JW: No, I think you have celebrated Hollywood through amateur pageants in real life. Well, Mike, I think you maybe have made the Mike Kelley Berlin Alexanderplatz!