Amid the nonlinear room scarved out of an aseptic and at times invisible set design, I couldn’t help but wonder what the reaction of an ordinary visitor, a nonexpert, would be to Martin Margiela’s exhibition at Lafayette Anticipations. Several times I went back and repeated the path from room to room; I was looking for traces of “fashion,” yet they weren’t there. Imagine an ordinary visitor, one who is ignorant of the history of Margiela the designer, who visits the exhibition unaware of any such legacy: Martin Margiela is simply an artist, on par with those legitimized by the system. We can even ignore the leap from fashion designer to “artist,” consecrated by Helmut Lang when he decided to exhibit one of Margiela’s very first art objects, a plaster cast of a jacket he designed in 1989, in an exhibition Lang curated at the Deste Foundation in Athens in 2009 (curiously enough, the year Margiela left fashion). The fact remains that what is on view at Lafayette Anticipations is an exhibition of contemporary art.

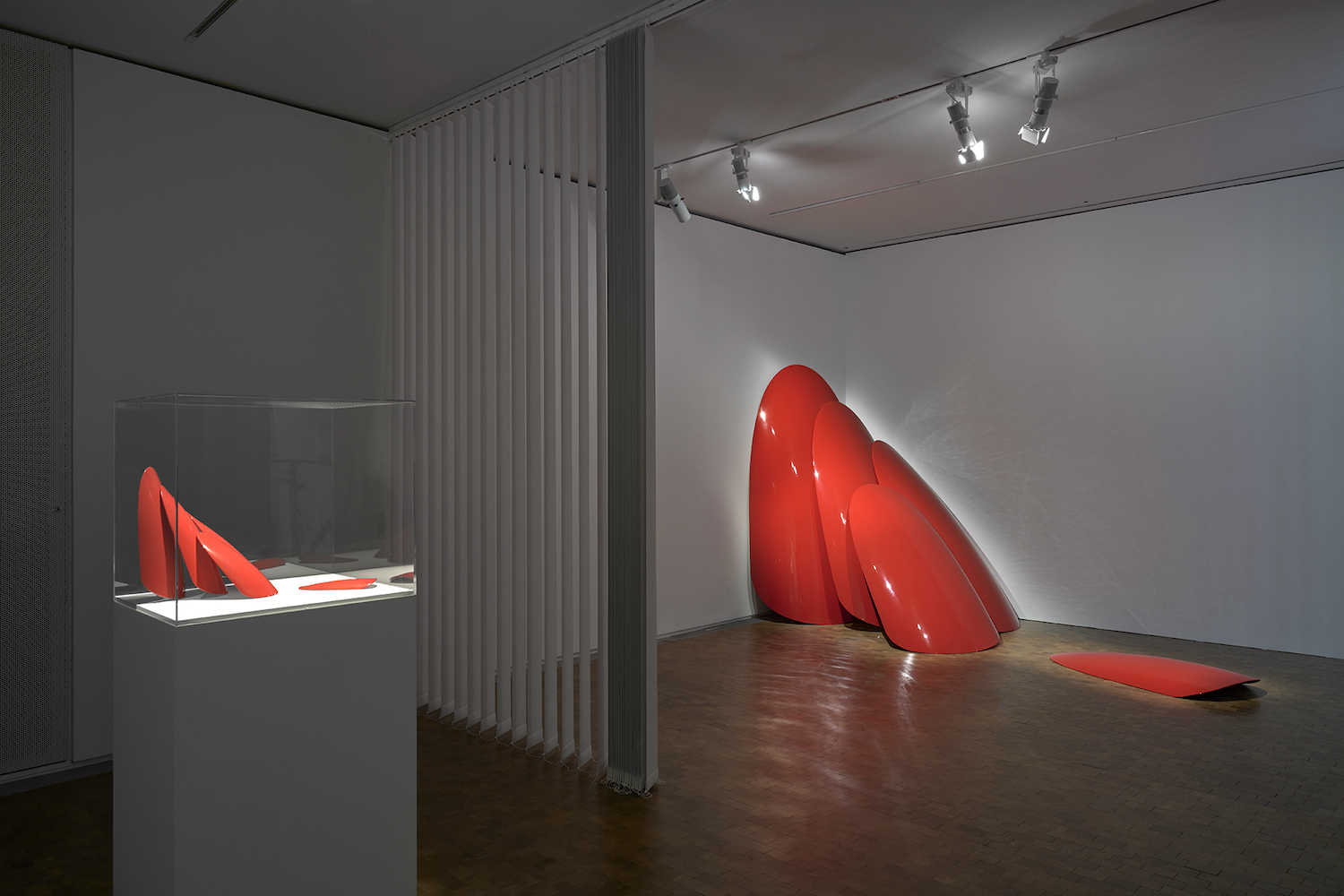

The body is always partially returned to in these productions. In the artist’s manner of evoking the body, the silhouette is a distant idea: specific curves, heads, skin, hair. They are obsessions or, rather, various vantages from which to observe and reflect on the object of art, whether it is the result of a process that has always been associated with fine art or the result of a hybrid path, derived from a singular vision of fashion and as a result notably free from contemporary clichés. At the same time that Margiela removed himself from the fashion world, his approach to art making embraced a unique sensibility of disappearance and removal. More than twenty works, including sculptures, collages, paintings, films, and installations, are spread over two floors of the building, which is accessed from the emergency exit. From the entrance one loses one’s bearings; a sense of bewilderment is persistent, heightened by light-filtering curtains with milk-white vertical bands arranged like partitions and movable walls. The quality of light makes the entire space seem vulnerable, and this spills over onto the works and onto the viewer. A feeling of absence, emptiness, dominates the exhibition: soft ochre monochromes are painted directly on the walls; the same tonality recurs in rounded shapes painted directly on the surface of plinths that usually foreground an object but that here do it differently, totally resetting the distance between support and work. This process is also repeated in some ways in the series “Torso” (2018–21), in which various bodily cross-sections are at one with their pedestal, both of which present the same chromatic tonality.

There is always an element of subtraction in Margiela’s works, whether it is the seeming void of Dust Cover (2021), for which we have no idea what is under the fake skin; or how he makes the invisible visible in the series “Film Dust” (2017–21), in which movie-screen-like surfaces, created using tiny glass beads fused to canvas, provide a ground for oil paintings of the dust that sticks to Super-8film.

The formal and fascinating rendering of Redhead and Vanitas (both 2019), heads made of silicone and natural dyed hair, makes me think of the late Italian painter Domenico Gnoli’s severe and soft details, particularly the locks of hair in works like Braid or Curly Red Hair, both from 1969, which feature perspectives that come so close to their subject matter that they reach a kind of manic limit for detail. Margiela’s heads, with faces covered by hair, are deliberately “wrong,” both surreal and all too real, as if to remind us that we are always out of focus with respect to art.