It doesn’t come as news that the Los Angeles art scene is growing fast. It’s evident in the sheer quantity of new galleries, events and museum exhibitions. But LA’s core strength is in its artists.

The art world generally aggregates in circles around galleries — everywhere it seems except Los Angeles. LA is different. Although galleries are the ultimate meeting point, for many reasons — mainly because LA’s expanded geography is difficult to navigate — art communities here often emerge around artist studios and art schools. Large industrial complexes are rented relatively cheaply and then divided internally into smaller spaces, each taken by an artist. Even if we are past the time when groups of artists might share missions and manifestos, it often happens that artists with similar attitudes come together in the same workspace. In a way, Los Angeles is to New York what Berlin is to London. Like Berlin, LA has a high concentration of artists; and like Berlin, LA might not have the strongest market, but it’s a place where art gets made.

One example of such an artist studio complex is the one shared by Stephen Rhodes, Sterling Ruby, Nathan Hylden and a handful of other budding LA artists. Rhodes is now showing at Overduin and Kite. Lisa Overduin — former director of Regen Projects for almost ten years — and Kristina Kite opened their own gallery recently. They don’t have a full stable of artists yet, but are building it gradually, seeking artists of any age and working within any media, although with an unstated but evident preference for conceptual work. The Stephen Rhodes exhibition is their third show. Inside, the gallery space is loaded with images and sounds. The central piece, Ruined Dualisms (2007), is a video installation featuring a hypothetical duel projected from 4 different vantages onto 2 screens (back and front). The same sequence — the preparation for the duel — is shot over and over again; but the fatal moment, the gunshot, never occurs, even as the sound component builds to an unfulfilled climax. You have the frame but not the picture, the setup but not the action; irony and frustration are the engines of the work. Every moviegoer is familiar with such suspense-building techniques, in films as divergent as Kill Bill and Inland Empire. But finding this cinematic move in an art gallery, deconstructed in a three-dimensional environment made of screens, paintings and crumbling ruin-like sculptures, is unusual and intriguing to say the least.

Way Out West

LA is far away. Its charm and free spirit come from this factor too. But out in the far West, galleries are often looking at Europe as a destination and resource. LA artists take part in major international exhibitions and biennials, and they are represented at fairs such as Frieze and Art Forum Berlin. It is in Europe, more so than New York, that LA galleries discover artists and conduct business.

Marc Foxx is one such LA gallery that pursues new European art. Their show of emerging Belgian artist Cris Brodahl consisted of black-and-white and sepia oil-on-linen paintings with wooden side panels that suggest a constructivist sensibility. Brodahl’s paintings have a dark mood and seem to come from a “new conceptual existentialism” that is especially evident in continental Europe. Her odd portraiture aesthetic is reminiscent of early 20th-century photography and religious iconography. If the figuration in these portraits is a moment of reality, the brushstrokes that erase portions of the anatomical features push them into abstract space. The wooden panels, hiding the paintings from each other and enclosing them within a delimited space, accentuate the impression of segregation and punishment. Terms such as devotion, ritual, esotericism and introspection come to mind.

At MOCA’s Focus series — dedicated to young LA artists — Matthew Monahan also pursues a Mitteleuropean-type vocabulary that references Thomas Schütte as well as Expressionism. Curated by MOCA’s Assistant Director Ari Wiseman, the exhibition consists of a large grouping of sculptures and works on paper presented as an installational whole. They are anatomical studies that recall the historical avant-garde in their multifaceted geometrical understanding of the volumes and masses of body parts.

Instead of presenting his sculptures in the classical museum vitrine format for which he is known, here Monahan more successfully shows them released from the glass case. They achieve expressive freedom as pure sculpture, disinheriting what still remained in his work of the relic and cabinet-of-curiosities cliché.

Sleight of Hand

At Cherry and Martin — a small but forceful young gallery freestanding in West LA among a row of shops that sells everything but art — Whitney Bedford shows her new series of paintings sourced from the iconography of magician Harry Houdini. Houdini here embodies as metaphor the will to escape from the rules and constrictions of the external world, and, moreover, the notion of challenge as an ideal to pursue.

As in her previous shipwreck paintings, the subject matter here is not just a means to painting, but is central to the comprehension of her work — this is also why the artist thinks of herself as a “conceptual painter.” Made with ink and oil on paper, the subject is merely suggested with quick brushstroke gestures. This technique emphasizes the flimsy physicality of the paintings, reinforcing the idea of escape and challenge. Referencing these issues, Bedford simultaneously imbues her work with a grand mythos and evasiveness.

Tricks and magic are in the air. Concurrent with Francis Alÿs’s inspiring solo show at the Hammer Museum, their project room features works by up-and-coming New York artist Jamie Isenstein. This show develops from a prank by P.T. Barnum who, in his American Museum in New York in the mid-1800s, fooled visitors with a sign that read “This way to the Egress.” Visitors that didn’t know that “egress” meant “exit” followed the sign thinking to enter another room featuring an exotic bird. Instead they found themselves outside the museum. Isenstein performs in the costume of an odd bird, staring at visitors from a gold-framed window opening in the wall, as if inside a painting. Constantly shifting from a fictional plane to a real one, her work confounds our belief in what we see. The exhibition recalls an amusement park with Surrealist objects, such as a door’s keyhole through which one can see one’s own eye reflected in a mirror, or an empty bird cage with a constantly swinging perch, suggesting a small phantom companion.

Isenstein’s show, curated by Ali Subotnick, coincides with her New York solo show at Andrew Kreps. The two exhibitions together make up a strange world of humorous and invisible presences, not too engaging and not too pretty either. Her work satisfies the order of the day: a bit of magic, performance, and low-budget but well-crafted sculptures and objects.

Return of the real

Ruben Ochoa’s work provides a reality check. For his first solo show at Susanne Vielmetter he realized two large installations and several photographs, built upon observations of the surrounding urban landscape. A young LA-based artist, Ochoa sees this show as the continuation of a work from 2006, when he placed at LAXART a large picture of a freeway wall that looked liked a piece of real estate transposed from the street to the gallery. A similar maneuver is explored in the new main work at the gallery. A set of pallets covered with concrete serve as bases for an unnatural landscape of concrete stumps with steel rebar armatures like skeletons. Through the lens of the LA landscape, Ochoa expresses a widening dichotomy between nature and artifact.

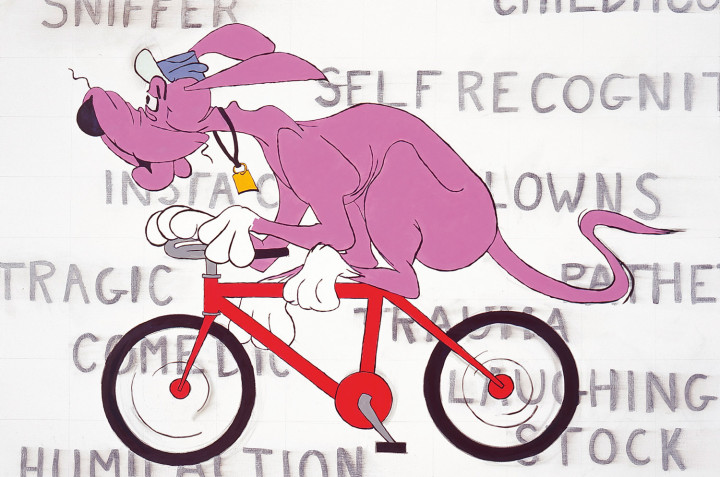

After three years, Sean Landers returned to LA for a second solo show of five new paintings at China Art Objects Galleries. They are a continuation of an LA-centric narrative started almost ten years ago at Regen Projects and then developed in several stages from an original group of clown paintings. In two of them, Nick Nolte is portrayed as a “huffer,” his clown-like face spotted with spray paint as a result of sniffing it. Landers says, “Sometimes people, when drunk or high, do things that are regrettable. That humiliation is interesting to me since so much of my writing has used that access point into the mind of the viewer.” The painterly crudeness evokes irony but also pathos. Three other paintings revolve around cartoon characters from the late ‘60s, when Landers was a child, combined with his signature texts in the background. In typical Landers fashion, the paintings function together as a multifaceted self-portrait of the artist.

Glitter in the gloom

At Peres Projects, darkness is exposed at the heart of glitter. Dash Snow’s show includes a number of new works, but the exhibition’s centerpiece — a performance that served as subject matter for the Super 8 film and photos on view — can’t be exhibited. About 30 guys, recruited from craigslist.org, were invited to the gallery at night to masturbate in a line, one after the other, while the artist and his assistants shot pictures. Snow felt his privacy was violated last year when New York Magazine published an article that probed into his personal sex and drug habits. So a large illuminated screen with the text “How much talent does it really take to come on the New York Post, anyway?” was the surface on which Snow’s performers came.

The actual art on display can’t replicate the un-sexy and pathetic sweaty dreariness of that night-time environment, nor does it satisfy the questions that come to mind watching the reactions of other viewers, some shy, some voyeuristic, some speechless. Like it or not, this is a show that we will be talking about for a while.