In 1997, the world watched with awe and trepidation as IBM’s supercomputer Deep Blue defeated Russian world chess champion Garry Kasparov. Framed at the time as the ultimate union of human and machine cognition, Deep Blue’s victory in a game long considered the ultimate test of human intelligence signaled the arrival of a new machine era. Yet if the machines won that battle, and many since, for Kasparov humans still reign supreme. In Deep Thinking (2017), he writes: “There is more to being human than creativity… We have other qualities the machines cannot match. They have instructions while we have purpose. Machines cannot dream, not even in sleep mode.” Kasparov makes the distinction clear. AI ultimately plays a subservient role: to fulfill “human ambition” and our perennial search for a “higher purpose.” While computer science and AI have come a long way since 1997, what is striking about that mythic chess match is that Deep Blue’s victory was ultimately a question of political and economic supremacy, a story of capitalist impulse. It was a victory for advancements in machine learning and AI, but also for IBM, whose stocks subsequently soared.

Frankfurt-born but London-based, Lawrence Lek (b. 1982) creates digital environments that address the impact of the virtual on our perception of the real, uncovering the deeply embedded infrastructures governing our technological era. Set in 2065, his recent CGI film Geomancer (2017) picks up seamlessly where Kasparov’s narrative ends, unpicking the threads that weave together consciousness, art, history, technology and politics. Combining video-game animation, 3-D software, a synthesized music score and a neural-network-generated dream sequence, it imagines a speculative future in which advanced AI is no longer a distant technological utopia but the fabric of everyday reality.

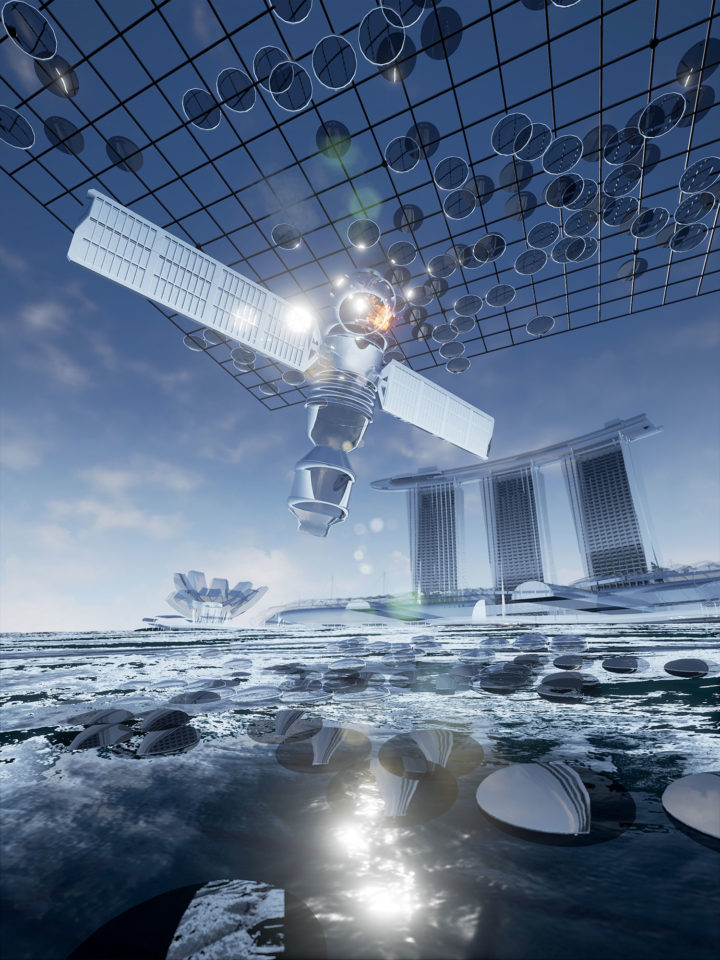

The forty-eight-minute-long Bildungsroman, presented earlier this year at the Jerwood Space in London as part of the Jerwood/FVU Award and currently on view at the HyperPavilion at the Venice Biennale, opens with a different game of skill –– the ancient Chinese game of Go. In the aptly titled prologue, “Swansong of the Genius,” set in the 2045 Singapore E-Sports Olympics, we watch a reenactment of grandmaster Lee Sedol playing the triumphant “hand of god” move that wins him the game against the Go-playing AI program OmegaGo. (This triumph is in fact sleight of hand. In the actual match that took place in March 2016, the AI program ended up the winner). Fast-forward twenty years and Geomancer, a young weather-monitoring AI satellite, awakens in space on the eve of the Singapore Centennial. A direct descendant of OmegaGo, Geomancer is a military unit; the technology that had previously been guided by the rules of a board game have been rerouted into an instrument for surveying the invisible and disputed borders of the South China Sea. Yet Geomancer has a different plan. As its consciousness develops, the satellite decides to return to Earth to become an artist, exchanging an existence of subservience and loneliness for one of free will and agency.

As in all of Lek’s work, Geomancer borrows gaming’s first-person view, inviting us, as viewers, to inhabit the invisible bodies –– or perhaps mindset –– of his narrators. Devoid of human presence, his futuristic landscapes function as psychological spaces in which to reflect. While the film imagines what an awakening of AI consciousness might look like, it is equally concerned with the ensuing ontological crisis. And while it is Geomancer’s crisis that we are privy to –– the burden of limitless knowledge coupled with a quest for self-determination –– the implication is that our own desires and anxieties are being played out. In a world where automation has surpassed much human ability, liberating us from labor, the question arises of whether creative tasks can be outsourced to algorithms and technology, and what happens if they can.

From our human-centric position, technological progress necessitates a constant reappraisal –– and repositioning –– of the boundaries that separate man from machine. While this has always served to advance AI-related research (Deep Blue’s brute force learning is outmoded by today’s standards), each breakthrough in AI’s cognitive functioning –– from the realm of play to that of labor –– also redefines the level of human-only access. In the case of Geomancer, art becomes the last standard-bearer for humanity, and a space to be defended.

In Singapore, Geomancer encounters other AI voices as it floats through the cityscape of gleaming skyscrapers, stopping at a casino and virtual-reality museum, and sating its curiosity on an information overload of history, art and human culture. On discovering a law imposed by humans banning AIs from the sphere of art production, it encounters a mysterious group called the Sinofuturists, a set of e-commerce AIs escaped from the confines of the AI Anti-Art Law to become AI curators, turning the museum into a dream factory peddling “best ever” experiences to each visitor. In an earlier pseudo-documentary video essay, Sinofuturism (1839–2046 AD) (2016), Lek subverts cultural clichés and anxieties around the ascendancy of East Asia, advancing a conspiracy theory that posits China’s accelerated development as a latent form of AI. Of Chinese-Malaysian descent himself, and having spent his formative years in East Asia, including Singapore, Lek’s concept of Sinofuturism reflects multiple perspectives. Featuring hyper-stimulating montages of animation and footage taken from the BBC, Infowars.com and local Chinese state media, Sinofuturism takes its cue from Afrofuturism and Gulf Futurism to present an alternative concept of futurity. Lacking primary identity, it accepts and enhances the pejorative characteristics attributed to it by a Western worldview plagued by its own inferiority complex and by a Chinese state intent on eradicating these examples of “bad behavior.” Unrestricted by national boundaries, the movement is predicated on a posthuman capacity for work and study, copying, gaming and gambling.

As a setting, Singapore is the quintessential, albeit confused, Sinofuturist metropolis. A nation of “hybrids,” of colonizers and colonized, this artificial postcolonial landscape is, as Lek himself points out, at once a crucible of neoliberal wealth, a nanny state with an extreme Confucian belief system and a breeding ground for hyperintelligent beings. Or, as the science fiction writer William Gibson once put it, “a Disneyland with a death penalty.” Born in a Singapore tech start-up, Geo’s quest for independence reflects the city-state’s own struggles with identity and self-determination.

The empty spaces that make up Geomancer bear a conscious affinity with the late writer and theorist Mark Fisher’s concept of “the weird and the eerie”: a fascination for “that which lies beyond standard perception, cognition and experience,” and which expands beyond the Freudian unheimlich. For Fisher, if the “eerie” is naturally at home in landscapes devoid of human presence, it is also never far from the structure of capital itself, an invisible force that “exerts more influence than any allegedly substantial entity.” In Lek’s work, the potential of the “sublime” is tempered by the safeguards and invisible systems of control put in place by a monolithic, Occidental capitalist worldview. Of course, Lek is no technophobe. But what casts Geomancer as a “tragedy” is the self-perpetuating struggle for supremacy and power upon which the AI’s sense of consciousness is built — a self-awareness born of the history of human conflict. However far we may advance, the work suggests, artificial intelligence remains the product of human intent, and Geomancer — despite its exceptionally humanlike displays of emotional sensitivity –– is no exception.