Imagining a direct dialogue with the sea while walking through the rooms of Fondation Carmignac, as the title suggests, is not a complex exercise.

In this exhibition, curated by LA-based curator Chris Sharp, themes such as solastalgia, eco-anxiety, and serendipity are constantly invoked through works by a transgenerational range of artists. One recurrent name appears in every room: the French filmmaker Jean Painlevé, who specialized in scientific films. One of the first works in the show is his gelatin silver print Buste de l’Hippocampe from 1931.

Scientific cinema was the instrument that enabled Painlevé to share his discoveries by making the invisible visible: as a alternative to traditional teaching, he saw cinema as a decisive vector for generating awareness, and ensured viewer interest by his attentiveness to aesthetics and rhythm, as well the flashes of wit that often accompanied his message. It was this injection of subjectivity into the scientific that gave a poetic dimension to his work.

Sharp analyzes our post-Enlightenment anthropocentric relationship to the animal kingdom through the research of various artists, using two in particular as the starting point of the conversation: Jochen Lempert and Michael E. Smith.

Lempert’s image of a father holding a baby surrounded by an aquarium — Untitled, (Aquarium, Toronto) (2017) — deftly sets the tone of the exhibition. Sharp writes in the catalogue that one of the moments when he began thinking about the intricacies of the animal-human relationship was when he read Nabokov’s Bend Sinister (1947), when he learned that the protagonist was repulsed by people who were amused by trained animals. He began to think about this sadistic attitude toward the zoological world in the works of Lampert and Smith. He writes, “For if, at first glance, it seemed that these developments helped frame and provide context to what these artists were doing, it was because these artists were already ahead of the curve in trying to rethink and reevaluate a post-Cartesian relationship to the animal kingdom or so-called nature.”

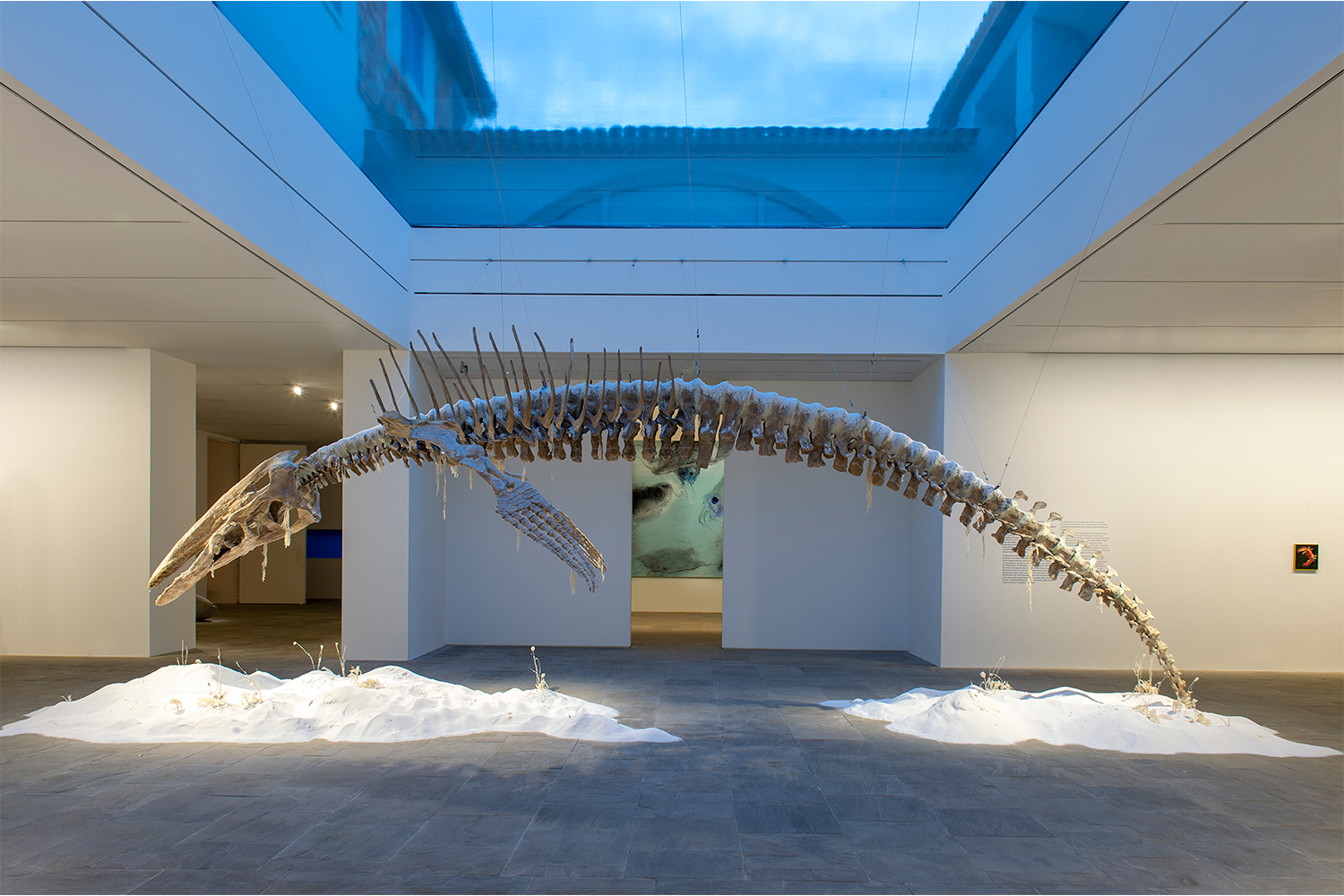

Another key work in the exhibition is Bianca Bondi’s resin skeleton of a whale, crystalized with salt (The Fall and Rise, 2021). The cunning artifice of this mineral-infused specimen perfectly embodies the man-animal anthropocentric clash. From this whale skeleton to Cosima von Bonin’s killer whale puppet trapped in a child’s desk, the show takes a didactic approach that could easily engage but also warn a younger generation. Indeed, and to its credit, it is an exhibition that will speak to a general public, perhaps primarily so. The foundation, with its semi-submerged architecture, is an ideal habitat for all these “creatures”: suspended colored resin jellyfish by Micha Laury, Lin May Saeed’s aquatic reliefs, Michael E. Smith’s seashells, Gabriel Orozco’s stylized subaquatic shapes, Jeff Koons’s lobster on a chair. The exhibition’s actual proximity to the sea only enhances the sense of the institution’s transformation into an aquarium-like showcase for art.

The news that mankind’s carte blanche exploitation of nature has led to anthropogenic changes to the environment, with likely catastrophic results, is now something of a commonplace. This outcome is at least in part due to Western man’s separation between nature and culture, as validated by contemporary exhibitions and museum presentations — an irony that Vincent Normand addresses in his contribution to the exhibition catalogue, alongside essays by Sharp and Filipa Ramos.

Such are the philosophical concepts that lurk in the depths of this whimsical exhibition, which should serve to remind viewers that more than eighty percent of the underwater world remains unexplored.kO