Kim Gordon: Let’s talk about Inside Job. Maybe we should explain what it is.

Jutta Koether: I wanted to come to New York to introduce what I was doing, which was painting, or rather conceptual art based and founded on painting, and all the baggage of what painting meant, particularly in Germany because that was where I came from.

KG: Like Jörg Immendorf…

JK: Perhaps, but also coming out of a yet-one-younger generation, and coming into this as a female artist. The early ’90s posed a new challenge to painting altogether. It was the arrival of a new conceptual art that I was interested in. I decided to work from within, to use the conventions, and the newly forming conventions, of what New York was producing in terms of being a young artist willing to “work the floor,” to operate site-specific. Performative. This meant meeting a lot of people and doing studio visits, something I was not used to. In Germany very few people had that kind of social behavior; we meet at the bar and that’s where one talked about art, took a position! In New York I adapted to conventions but altered the rules toward my needs and abilities. I was interested in interviews and conversations. I made paintings and let people participate in various ways; you could walk on my paintings but you could also have a sit with me, talk either about the painting or painting in general or Germany… They were all one-to-one encounters. It was through that that I learned about certain legacies and practices, such as Lee Lozano for example.

KG: I think I remember coming there.

JK: I think you were there. Every day then I would write a report of what had happened. I wouldn’t type it but write notes and make notebooks, and the next day all the visitors could see what I had written… My commentary on these people and the experience itself. People who came after two weeks read all the commentaries that I had done on the other people as well as the progress on my paintings, my feelings about the whole thing — a kind of emotional rollercoaster. Inside Job was, among other things, about getting access to people in the art world; I like this word play.

KG: Did you show that painting?

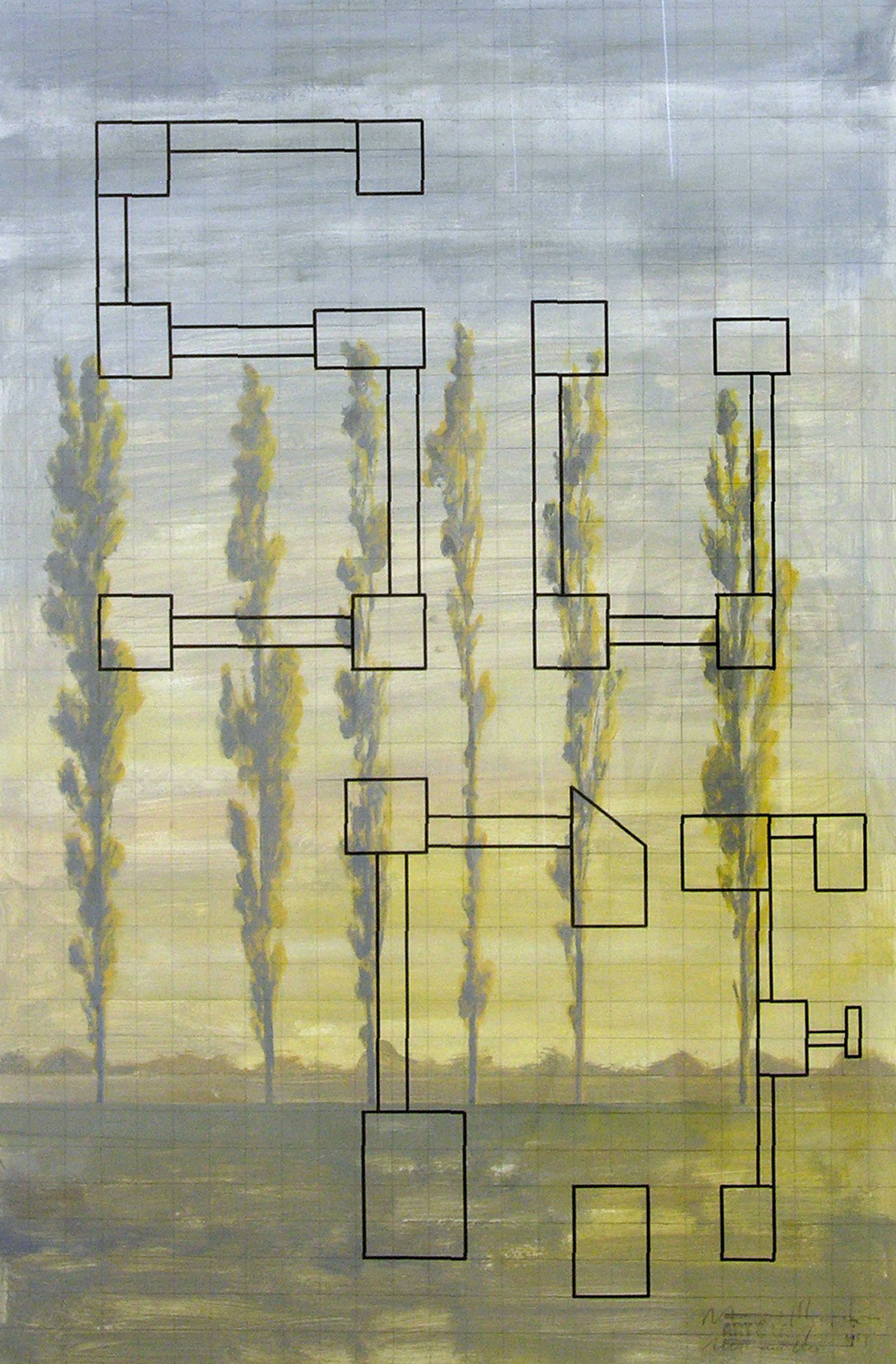

JK: It was shown at Friedrich Petzel’s and Nina Borgmann’s loft; she was his partner in his first gallery and at the time they were interested in possibly showing my work. They showed it there, but then it was rolled up until it was shown again in 2006 for “Fantasia Colonia,” at the Kölnischer Kunstverein in Cologne.

KG: And when they showed it, did they display it differently? Did you have some explanations?

JK: They showed it bare. Just off the boat, or the studio, so to speak. Formally it resembled an Antonius Höckelmann painting. Very layered, too colorful, kind of raw. But then there were the drawing books and the commentary book with the reports about the visitors too. They functioned as evidence of the experience, as a diary, but also as a kind of manual to understand figures, motives, composition in the painting. A kind of manual to “read” the painting. The painting was kind of chaotic. The composition had these weird sexualized body parts, the figures were trying to communicate but they couldn’t. It was very dense and diaristic, and it was almost impossible to like it. So the actual manual books as well as the catalogue called The Inside Job containing all the writings and some documents need to be considered external elements of the painting itself. Altogether The Inside Job was a way of penetrating a social fabric (the Downtown New York art world around 1991) while suggesting and starting my own brand of weaving at the same time. The literal platform for this was the semi-public making of a painting in the studio accompanied by suggestions, desires and projections by others through the conversations that took place with it, on it, near it.

KG: You didn’t go to art school. How did you meet Martin Kippenberger and Michael Krebber? Did you meet them in a bar?!

JK: I met Kippenberger through other artists and through work. His visit to Cologne was a big event and I interviewed him because I was interested in his way to be an artist. I happened to be in Cologne — Krebber is from Cologne too — and when Kippenberger moved in 1980 or ’81, I started meeting him, although I had briefly met him when he was still in Berlin, again through other artists. Cologne was this sort of place where people met; I also met a lot of Americans, way before I met them here.

KG: What was your relationship to these people?

JK: I was around and part of a certain development. I wrote about people — that could be a measurement perhaps. I was part of a culturally active environment. My home base though was not a gallery or the bar but Spex magazine.

KG: What about feminism? There’s this great picture of you and Cosima von Bonin with the machine guns… I know it’s a cliché but still it comes off in an intriguing way.

JK: That “infamous” picture of a sort of guerrilla troupe was almost like a mock of a feminist take, especially because it was initiated by a guy, Hans Jörg Mayer. We played along and I think each of the participants took it in that way. For me it was almost like a goodbye picture because I was leaving. It was hard to figure out any kind of role for me in Germany in performance art. It is funny that it still circulates here and there. It resurfaced truly in the show “Make Your Own Life” curated by Bennett Simpson at the Philadelphia ICA in 2006.

KG: You told me once that Yoko Ono was important.

JK: Yes, but that was when I was really young. As student I got interested in the trajectory of “women’s art, feminist art” and the renegade even within that… I looked at Ulrike Rosenbach, Rosemarie Trockel. Those were the accessible ones. I read a lot. The problem zone I liked to dig into though was painting. There were not that many models rethinking painting by women around. But at some point I did discover Maria Lassnig.

KG: But then there was Kippenberger and Albert Oehlen or later Merlin Carpenter…

JK: Sure, and truly challenging practices with painting. One of my first projects was titled “Smell of Female” after the record and song by The Cramps. I also like to incorporate living social facts from a point of view that is shaped by the female experience. I like to do things with painting that men cannot do. And yet finding the knowledge of the other doesn’t mean to limit yourself, or self-marginalization. I like tactics. Not to stabilize expectations but to confound them. Even those of your friends. Even your own.

KG: This is probably why I’m drawn to the scene of Simone Forti, Joan Jonas and Yvonne Rainer — people whose works are not object-directed. It’s a little more elusive in that sense.

JK: Yeah, but if you address in an analytical way the mechanism of how things are established, Forti, Jonas and Rainer really question those mechanisms; it’s not about fulfilling the anti-role. To me that was really like another proposition, and a huge achievement. Now for me there is always that other site: painting. How to construct propositions like the ones above through painting.

KG: It’s funny. When we do music performances I always found it so great to perform in this art context. It’s not that I’m not nervous but I just find it incredibly enjoyable cause it seems people are looking in another way. In the art context it doesn’t matter if people don’t think this is great — it’s a moment where the judgment is suspended.

JK: You just create a moment, what I call “invisible brushstroke,” and that’s why I like performing, beside the fact that it’s not an object after all. It’s a very intense moment, for me similar to when I look at an artwork that is really fascinating.

KG: Do you see it as an expanded form of painting?

JK: Sort of. It is expanded, but it is the perception that is getting expanded, not an object, not a thing. Performance is an act to establish possible afterimages that then will reflect back on the paintings. And sometimes I rather set it up like a zone, where you can have other experiences. It’s like The Dream House by La Monte Young, but only for a moment.

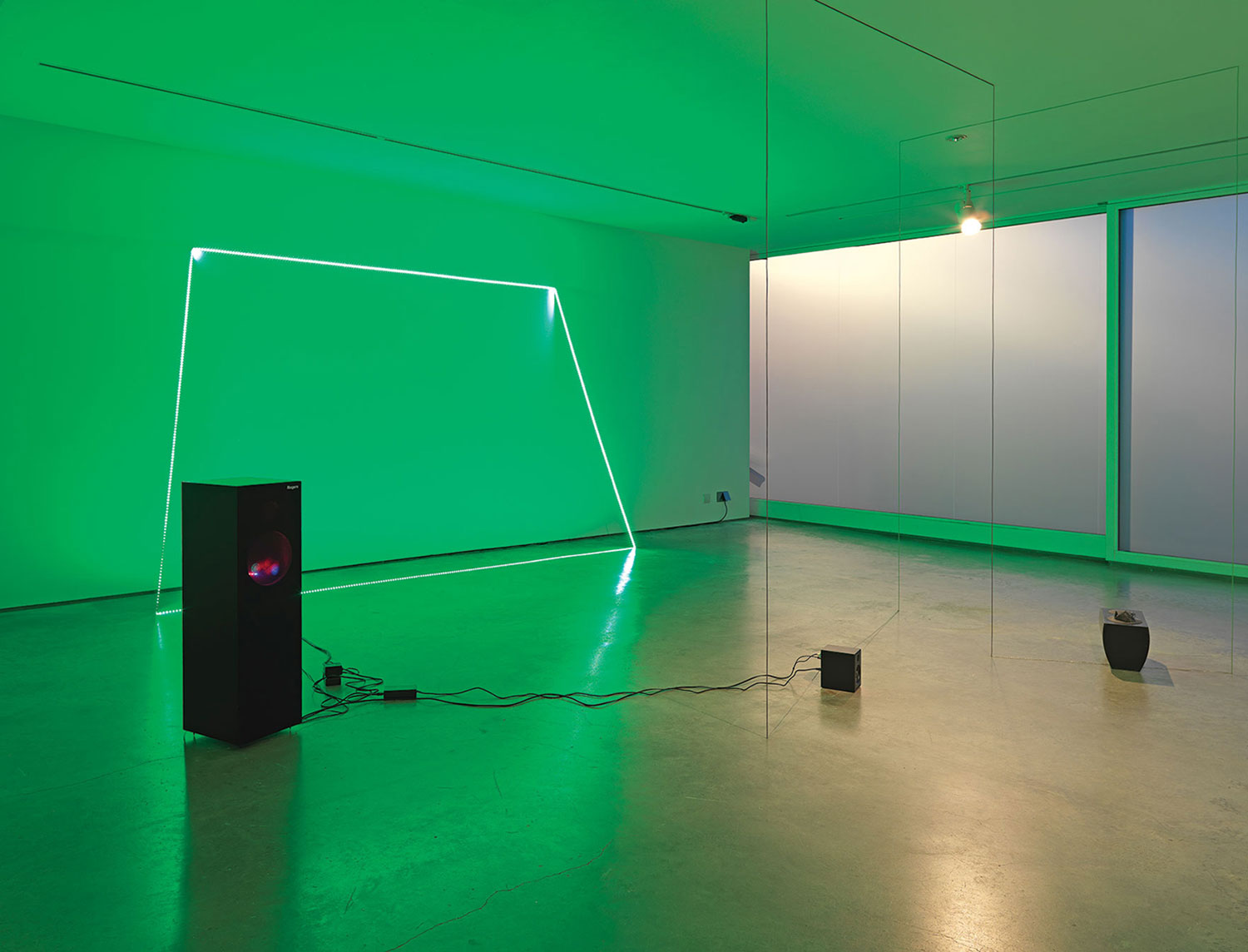

KG: I really felt that when we played in Paris at Sutton Lane in 2008. That über small space that was so pure with no desk or furniture…

JK: Not to forget that the painting we played in front of was that stark remake of Cezanne’s Bathers that is in Philadelphia, where there are these women who are wandering around without knowing what they are really doing and yet they form this perfect composition. I thought that was a really great interaction, working as painting as well as a backdrop.

KG: And we didn’t know what we were really doing!! I really liked the “Dead Already” show at Reena Spaulings Fine Art in 2007. I could write pages. We should because it was not really documented and it would be great to try to reconstruct it. And I loved the crown, the carpet, that blush nude body carpet to re-envision feminism, having Isadora Duncan’s teacher coming down and teaching a class and these art crowds; there was a lot of energy put into it. That happened in a gallery situation and that’s why it was so successful.

JK: It was very much related to the downtown New York community, a small noise music scene, young artists, current and former students. I’m interested in investigating the various roles and functions the artist has these days in a very particular environment. To keep questioning this as well as questioning the objects in these settings. Collaborations, collective practices and performances are all part of an ongoing investigation that uses painting as core, enigma, trigger, trash pile. I put them in situations that are questioning their existence, their tasks, functions, history. And in the long run those kind of exchanges really are the foundations for new form and thinking onwards.

KG: Besides me you have collaborated with John Miller, Steven Parrino and others.

JK: Yes, and this makes me think I should take care of that. My interest in the future is to try a different set of rules of engagement. So instead of having an idea about three or four paintings, I’m trying to establish concrete ideas that can be embodied in a person but like a commission, an imagined commission; making a painting from that relation, and with every work a text would come, so that it would work like a classical painting with a lot of preparation. I’m trying to figure out a different way of speaking to somebody.

KG: It seems the opposite of what interior decoration does, which is what art is doing pretty often. You said that you did the painting that was last year in the Independent specifically for Sutton Lane. What was about that painting?

JK: First of all the format was the art fair and there was a demand to make a new work that had to fit into a specific place and space. But the core, what is actually on the painting, was deeply connected to Gil Presti and Manuela Campoli, who run the gallery. I wanted to have a motif related to them, based on a real experience. Reena Spaulings had done a show with Sutton Lane in Brussels titled “The Belgian Marbles,” strongly referencing Marcel Broodthaers and his connoisseurs like Krebber. Broodthaers is a focal point also for an earlier show that Gil curated at his gallery in Paris called “Signatures.” To share the enthusiasm and thoughts surrounding those events, we all took this trip together to the Brussels’ Musée Royaux des Beaux-Arts and looked at the Broodthaers collection. There was this piece with the red pot and the mussels and I decided this is the iconic link between all of us (me being so invested in red painting.) At the same time, when we were discussing the possible work to bring to the Independent, there was this question around “what people want.” I decided to insert things also using the essence of that desire, of what they wanted, or perhaps to make a painting that articulated this thought; not to fulfill desire but to make a piece that asks the question: “What is it that you call desire?” So there’s the pot, the collage, the liquid glass and these brackets, which are moving themselves. The whole piece came from these premises, and the whole thing is not “complete” in that sense. It is an open landscape with a lighting rod going through a pot, and things spilling out of the pot that become too real, too literal. I titled it Bitches Brew (which is of course the title of the classic Miles Davis album, basically establishing a new genre of jazz). But it’s not that we need all these things to understand the painting.