Over the course of nearly seven decades, Jasper Johns has produced some of the most iconic art in America and influenced countless artists and movements — notably Pop Art. From his early paintings of flags and targets of the 1950s and ’60s, to his later Usuyuki series from the 1970s and ’80s that makes use of colorful cross-hatching, his has been an art that insinuates itself coolly within both art history and the popular imagination. Now, across two museums — the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York — Johns’s contemporary cachet is being tested through the display of sixty-five years’ worth of work.

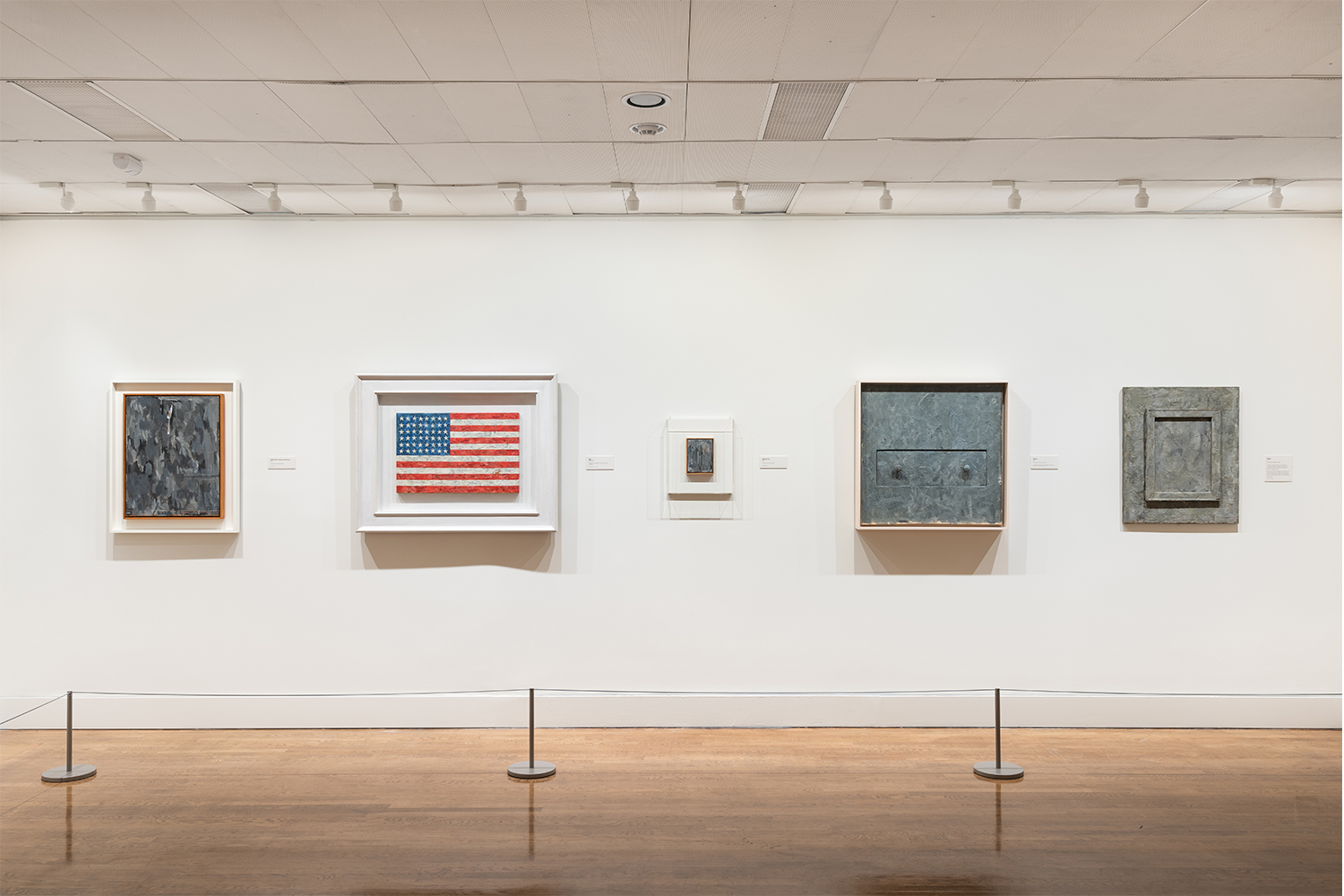

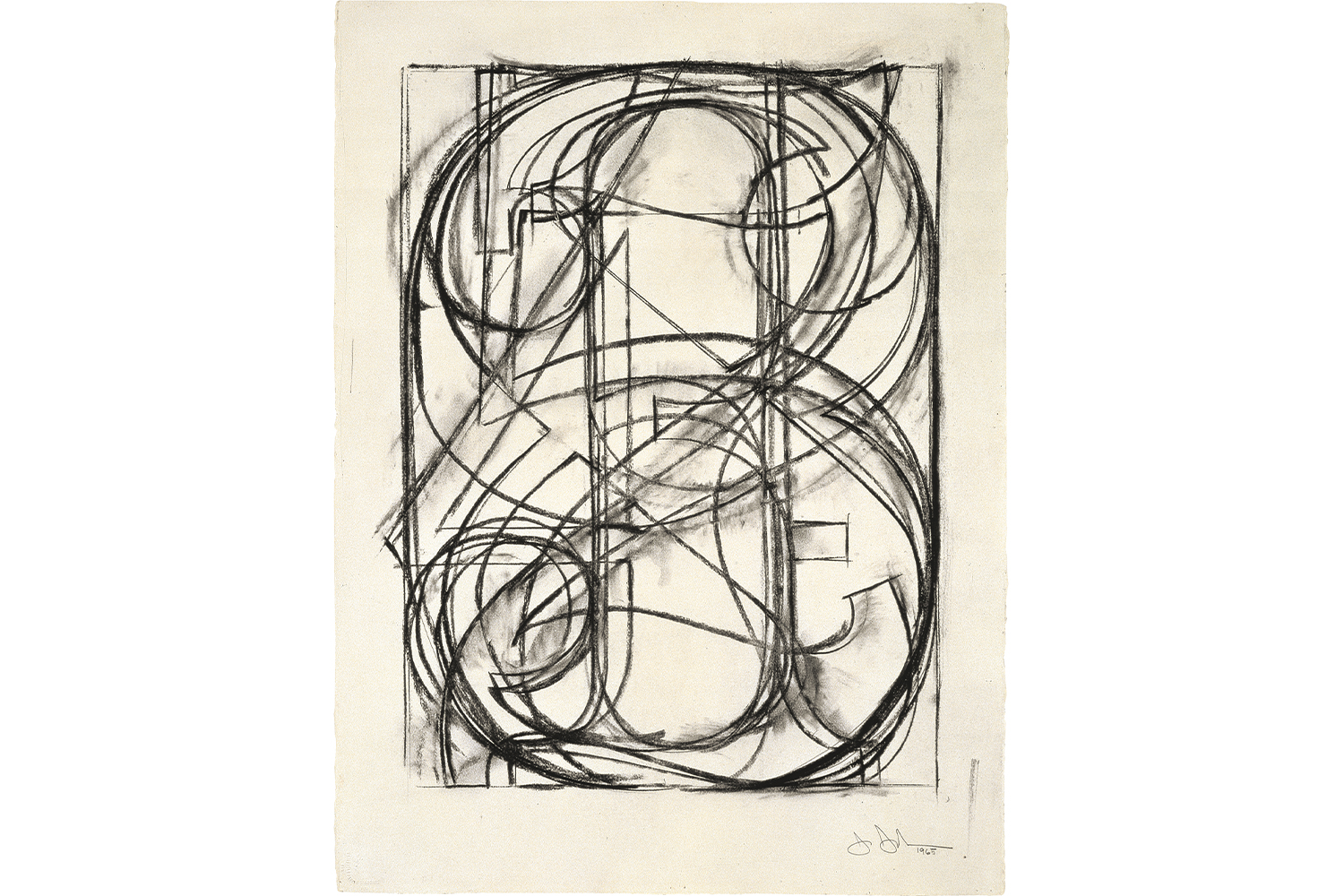

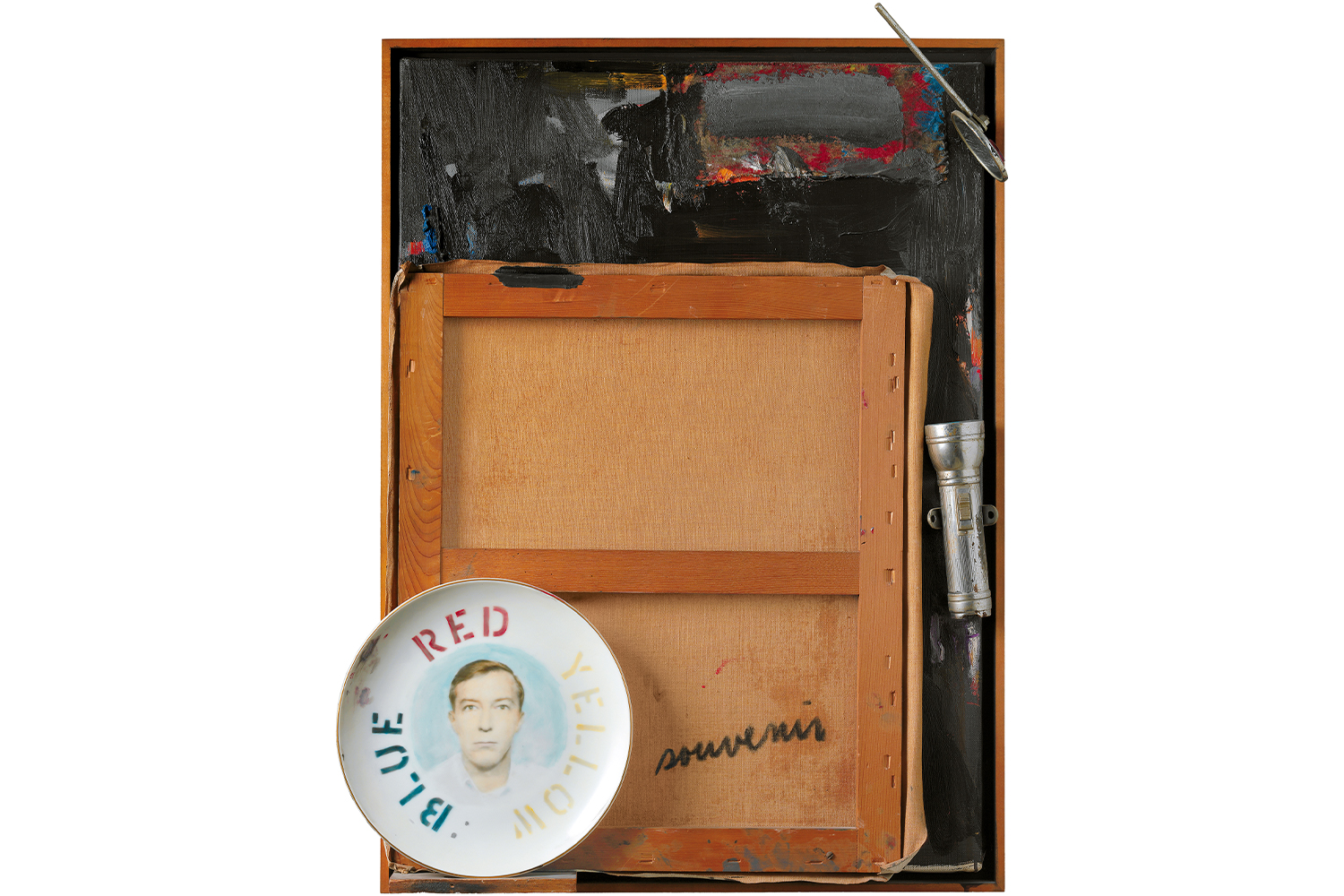

Cumulatively, the shows are composed of more than 550 paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures, as well as numerous photographs and personal objects—like Johns’s copy of Marcel Duchamp’s The Green Box (at the Whitney). Together, the exhibitions offer viewers an unprecedented opportunity to discover the depths of one artist’s oeuvre —not an easy task given the number of works in these shows — if they make it to both museums. The works have been placed in ten different thematic sections by the curators, Scott Rothkopf (in New York) and Carlos Basualdo (in Philadelphia), with sub-themes at each museum. “Flags and Maps,” for example, falls under the “First Motifs” section toward the beginning of the Whitney’s exhibition, and contains some of Johns’s most well-known, iconic works: Three Flags (1958), an encaustic on canvas work of three American flags, each on top of the other; Flagon Orange Field (1957), an encaustic on canvas painting of an American flag set against an orange backdrop; both flank Map (1961), a large (roughly two by three meter) oil painting of a map of the United States with the names of the states, like “Georgia,” where Johns was born in 1930, stenciled in the relevant location on the map. Done in hues of orange, blue, and red, the composition looks like an abstract painting from a distance, gaining more precision the closer you get, only to have the map’s accuracy frustrated by the vigorous, inexact application of paint. Johns here, and in many other works, mirrors a visual approach to everyday objects like maps and workaday symbols like numbers: they cross our visual field, but we don’t focus on them long enough to make out their details — when’s the last time you noticed the font of a numeral? In Philadelphia’s “First Motifs” section, subtitled “Numbers,” the focus is on another recurring subject in Johns’s work. This section of the show in Philadelphia is more intimate than its related room at the Whitney, with smaller works on paper, including Figure2 from 1963, a graphite wash and charcoal work. Here, the numeral 2, outlined in dark charcoal, blends into the grayish graphite wash, fading in and out of view with a change in perspective.

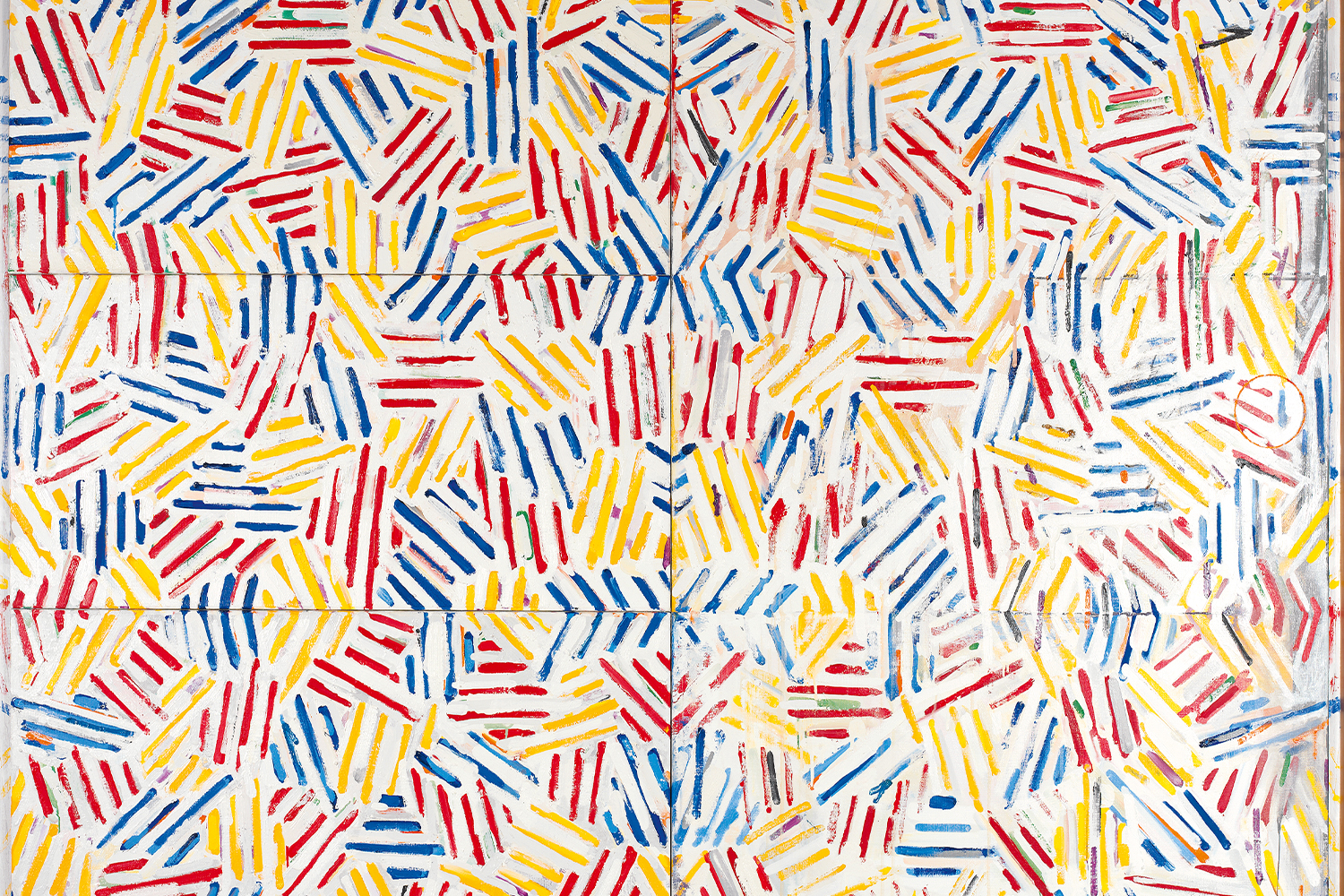

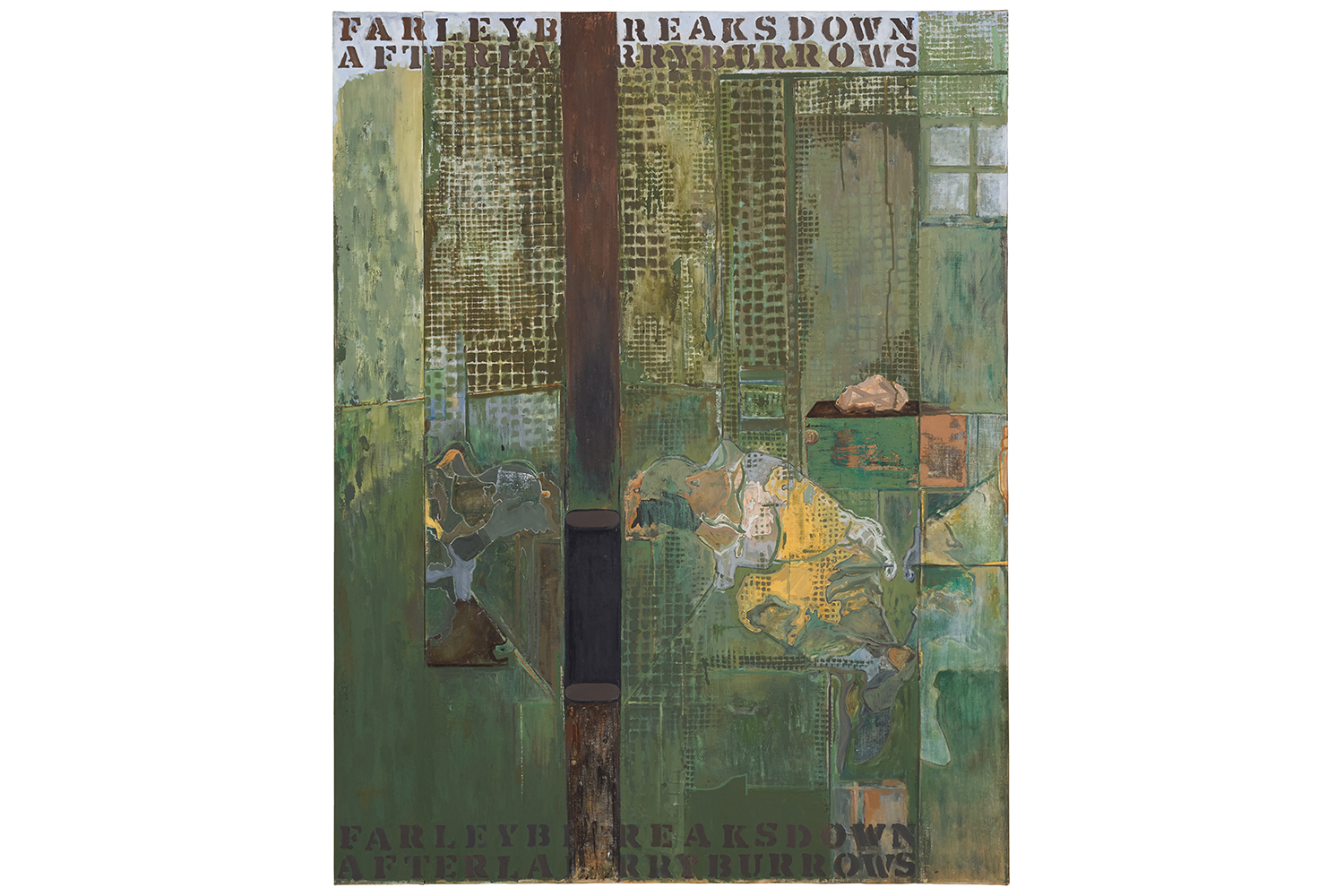

Across both locations, the themes Rothkopf and Basualdo have focused on interplay with one another, showing Johns’s diverse yet circumscribed pattern use: maps, flags, targets, numbers, and a smattering of Mona Lisa images and brooms about does it. The commonness of these symbols and objects lends itself to a reading of impersonality, of heady distance. I’m not sure this is the right way to read Johns’s early work, however: while it is true that the motifs that recur in Johns’s work are prevalent in our everyday lives and don’t typically have any “personal” or special qualities to them — a map is a map — the manner of making clearly shows the artist’s hand. In Three Flags, for example, the encaustic material encases each brush stroke, fixing it for time like a private archive. It’s not until work from the 1970s and ’80s, however, that we really see what many viewers might consider a personal side to the work. His Spring (1986) and Winter (1986) in each museum’s “Doubles and Reflections” section (within the “Mind/Mirror” area) parallel each other, offering a (presumably) male figure set against a background filled with an exploding star/leaf design, canvas frame shapes, and forms from some of Johns’s other works, like the pattern from his Usuyuki series, as well as other well-known images. The duck-rabbit occurs in Winter, while Rubin’s vase appears in Spring, each playing off the doubling theme of the section as well as Johns’s use of duality (spring/fall, summer/winter) in the titles of the series.

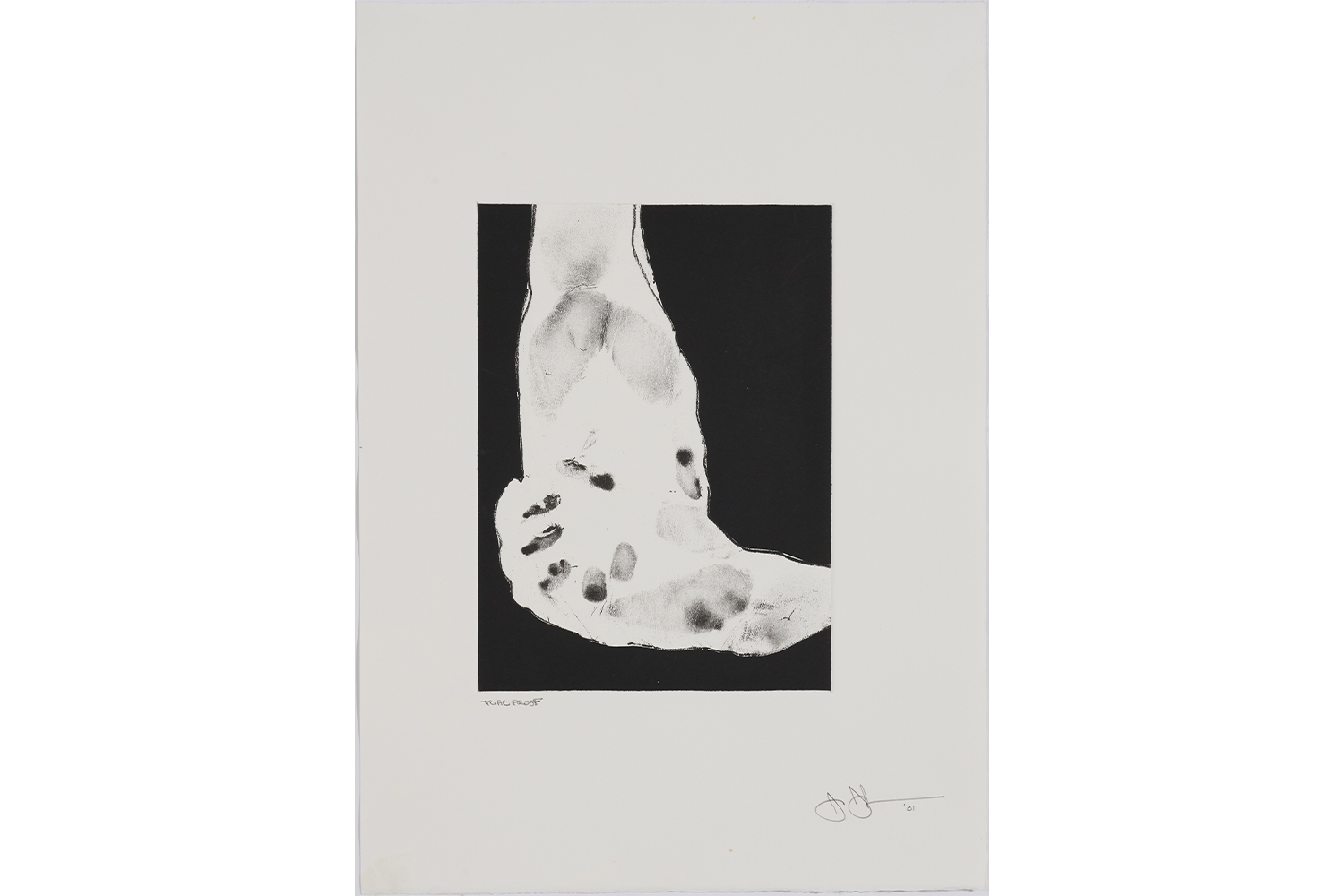

Some of these same symbols can be found in Johns’s work until the mid-2000s, at which point, then in his eighties, he turns to portraying skeletons. Death is a likely theme for anyone in their eighties, and with death comes rebirth, of a sort anyway. If there is a scion of American postwar art who has passed the test of contemporaneity for each epoch they have been a part of, it is Johns, who now, at ninety-one, lives anew with each artistic reiteration.