The CAPC – Musée d’art Contemporain is contained in a cavernous converted nineteenth-century warehouse in Bordeaux. It is a fitting venue in which to show the work of Jasmine Gregory, an American artist living in Zurich, whose art has a transformative, repurposed intention in both its materials and the way it beckons the viewer’s gaze. “Si je ne peux pas l’avoir, toi non plus” (“If I can’t have it, neither can you”) is her solo exhibition in collaboration with the roving Centre Culturel Suisse. The exhibition is divided into four rooms, and Marion Vasseur Raluy (who co-curated with Claire Hoffmann) explains that Gregory “had a vision as a whole, but you can feel that each room has been thought by itself — each room is a whole installation.” Everything was custom produced for the show except the preexisting paintings. Gregory came to the CAPC with materials but had no preconceived ideas; her subsequent experiments in situ have turned the mundane into a confrontation with what makes a work worthy of consideration.

The first encounter is with three commercial vitrines, the kind of display case readily found in phone repair shops (these were in fact sourced from Bordeaux’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs et du Design). One is peppered with loose coat hangers; two are thrown on their sides; all three are eerily lit from below in red neon. The vitrines function as a barrier to the three abstract paintings on the wall behind them, coalescing as a meditation on value, filters, and repositories.

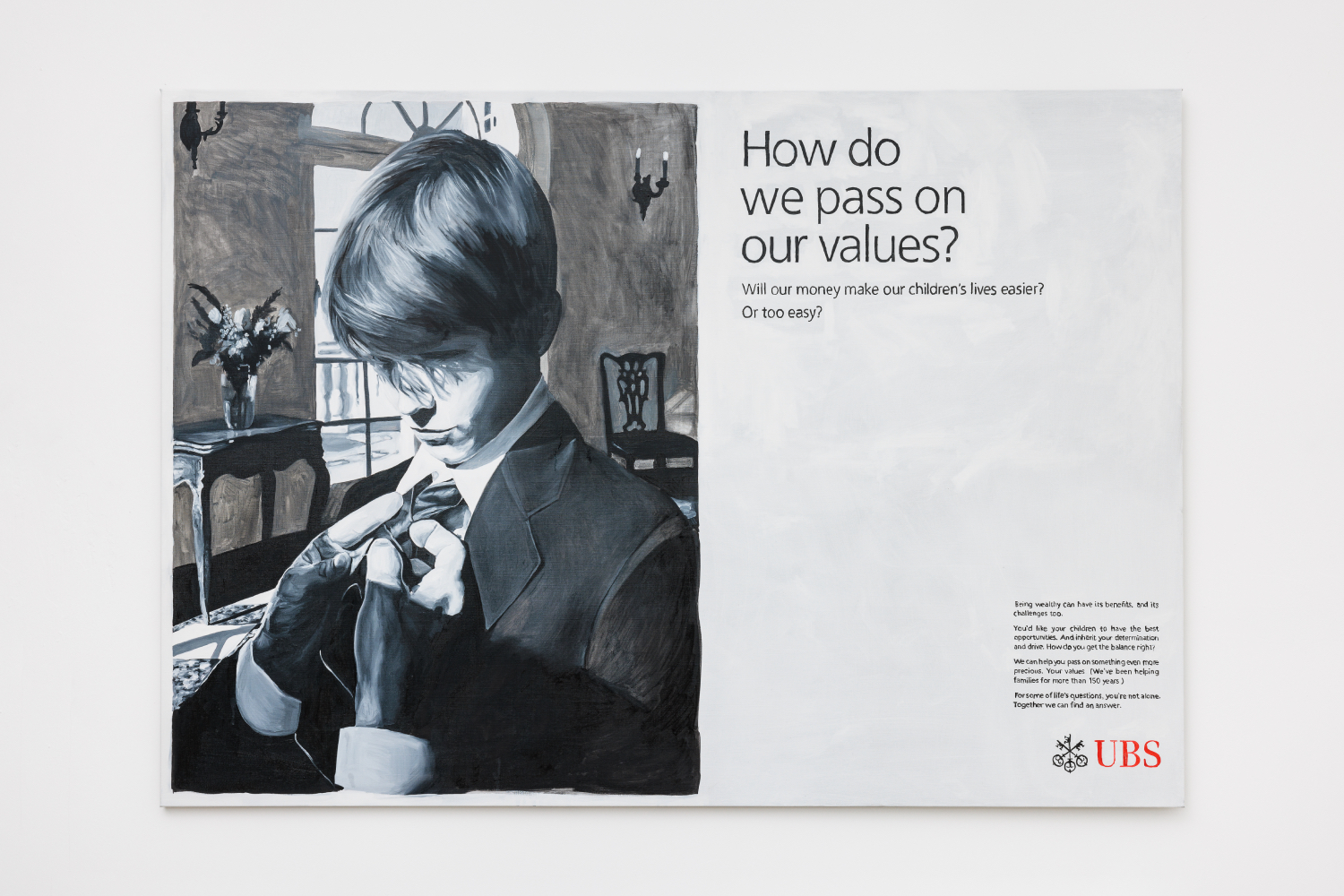

The next room features three figurative oil paintings from the artist’s “Estate Sale” series (2023). These replicate ads from a Swiss bank — the kind of glossy, meaningless notices seen in airports. The ad copy seems fabricated, but the absurdity lies in the fact that these paintings replicate existing ads (“Being wealthy can have its benefits, and its challenges too”; “Will our money make our children’s lives easier? Or too easy?”). These ads are hand-painted — Gregory’s gestures are visible in how the paint lays on the canvas — rather than commercially sleek. Her artistic rendering of the grotesquerie around financial obsession dovetails into a critique of the market system into which art too is beholden. The advertisements appear ridiculous in a museum context, yet also reckon with the increasing commerciality of the art world at large. The paintings wink at the Pictures Generation, questioning the authenticity of art edging on consumerism. They challenge the viewer to think about how such socioeconomic conditioning influences the way we interpret images.

The painting triptych pivots into groupings of micro-installations illuminated under a rotating spotlight; each pile of debris is given a brief starring role. Although sometimes Gregory buys additional accessories (like synthetic hair and plastic shoes), she often integrates detritus from her studio directly into pieces, where packing materials and items she ate become part of the work.

In the last room “you have this feeling that she sliced the walls. You open them and see what’s behind the painting,” says Vasseur Raluy of the blue-lit space where three white panels are propped up, revealing sealed trash beneath (notably a Champagne bottle holding two dried roses that the artist found on the street in Zurich). Gregory here nods at Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980), creating a parallel between the body’s secretions and what spills out and transcends the image framework. A final painting, Investment Piece (2), (2022), a depiction of an ad for Patek Phillippe watches that foregrounds an awkward father/son duo, is hung in the corner. The sinister figures stand for privilege and generational wealth, creating a disagreeable understanding that, quite contrary to the exhibition’s title, what is allowed for some is not for others.

While there are implicit references to Frantz Fanon (a psychiatrist and militant anti-colonialist) and Calvin L. Warren (an Afro-pessimist philosopher), Gregory overtly skirts identity politics in her show — the wall text evokes nothing about race. “She wants to be careful with herself and doesn’t want to be tokenized,” Vasseur Raluy explains of this refusal. Elsewhere, Gregory has stated: “My goal is to make work that is only obliged to itself.”1 “She has so many references in her work — it’s very rich,” Vasseur Raluy says, “but she’s also very intuitive… It’s a really beautiful pairing.”