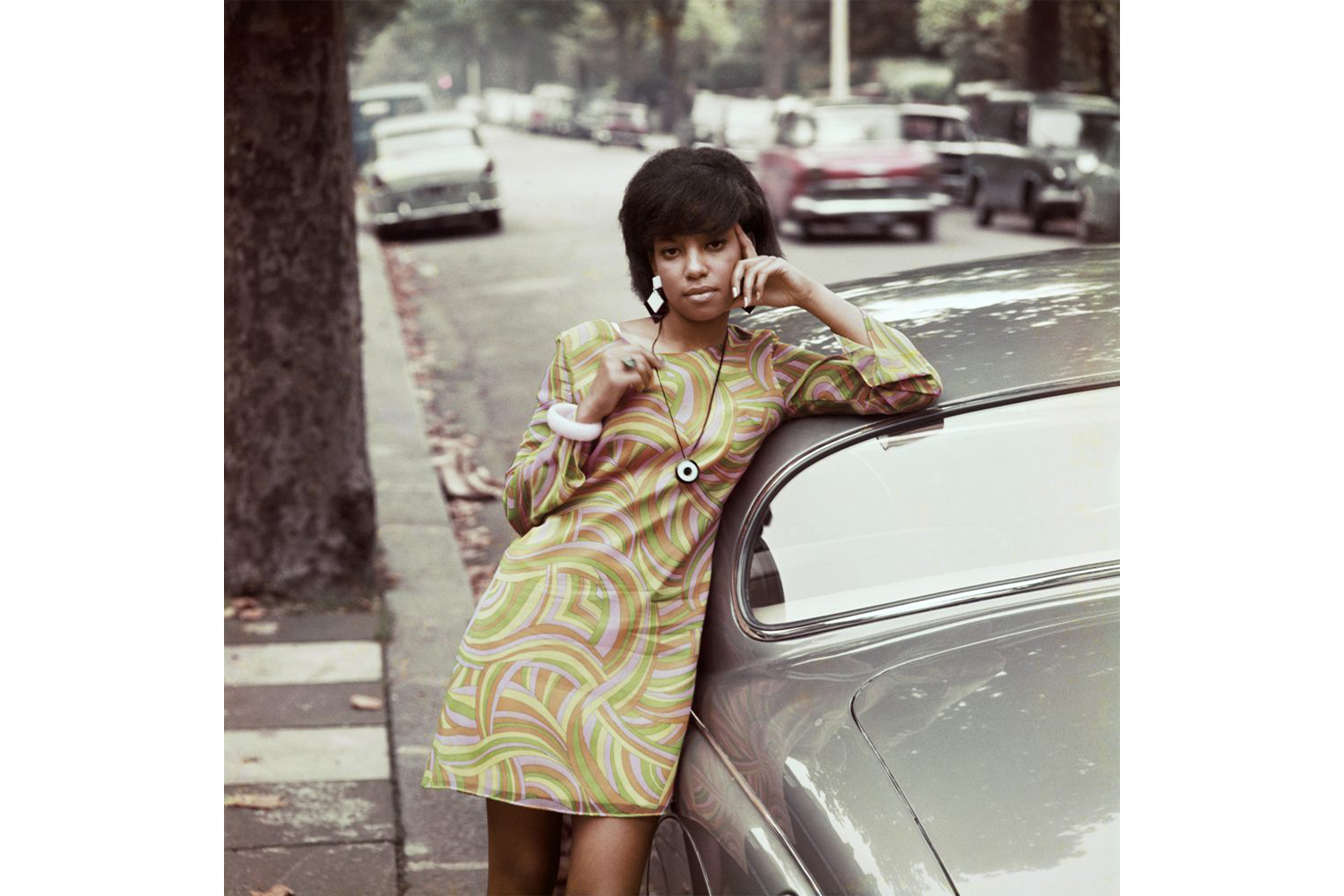

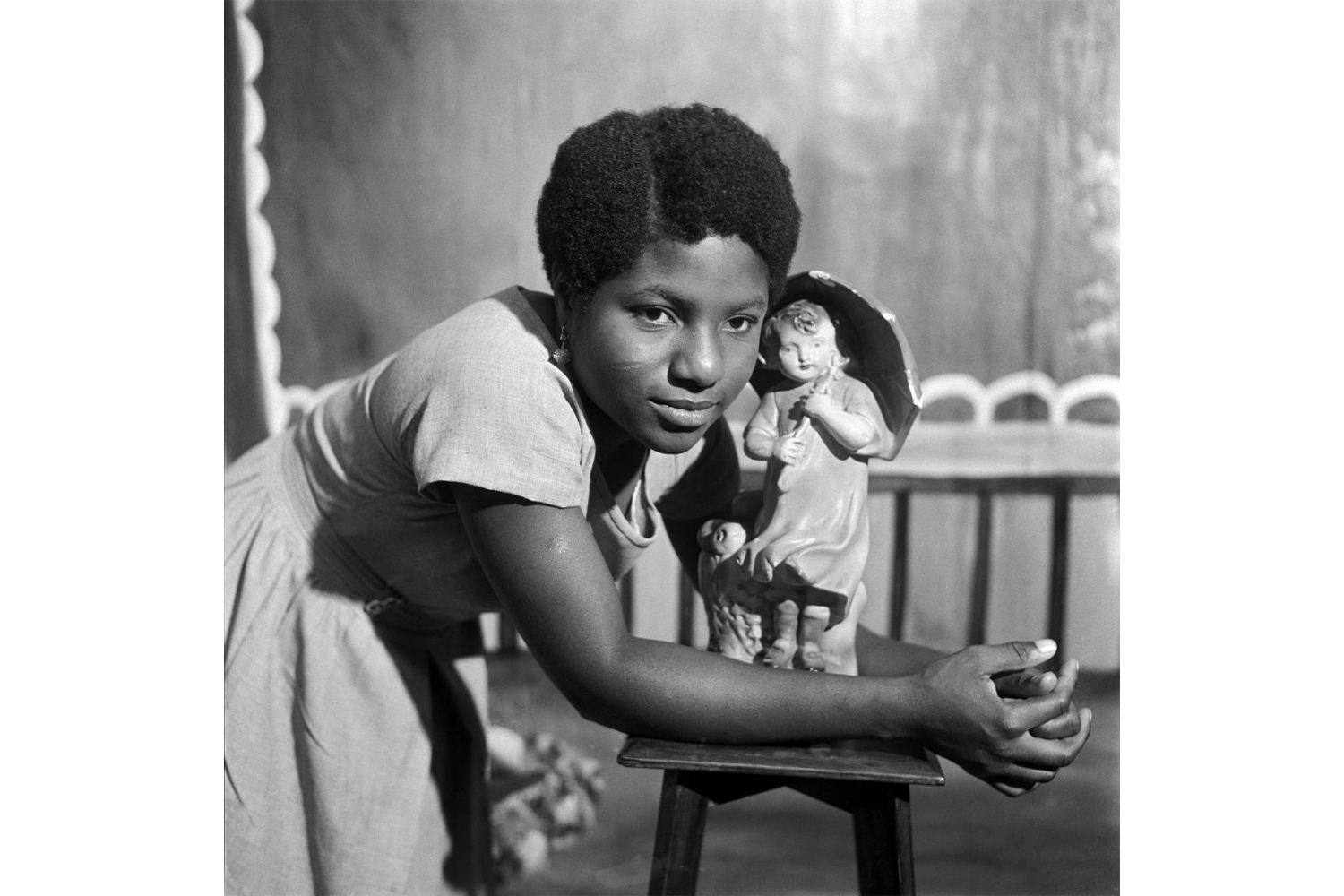

Selina Opong, Policewoman #10 (c. 1954), in the crisp uniform of a new generation of professional Ghanaian women, stands to attention at the entrance to “James Barnor: Accra/London – A Retrospective.” With her right arm raised in salute and her gaze reaching beyond the setup of formal African studio photography, Barnor’s image appears to anticipate oncoming revolutions of modernity — decolonization, sexual politics, and the diasporic experience. Just over a decade later, Drum Cover Girl Marie Hallowi (1966), lounging in a convertible car and rendered in saturated color, locks eyes seductively with the viewer from below. Marking the divide between respectability and sexual freedom, the optimism and vitality of both these women permeates the exhibition as a whole.

The versatility of Barnor’s photographic practice — from studio to street, and from swinging ’60s fashion to the arresting portraits of Kwame Nkrumah at the moment of Ghanaian independence in 1957 — is resplendent here. Recovered from the artist’s archive of over 32,000 images, the quality and scale of these prints is astonishing given his historical omission by the Western art world. A starkly lit shot of Muhammad Ali, shown from behind in preparation for his 1966 title defense against Brian London, seethes a potent tension that portends his third-round knockout. For assistant curator Awa Konaté, such iconic reportage typified Barnor’s status as an artist long before his acceptance into the institution.

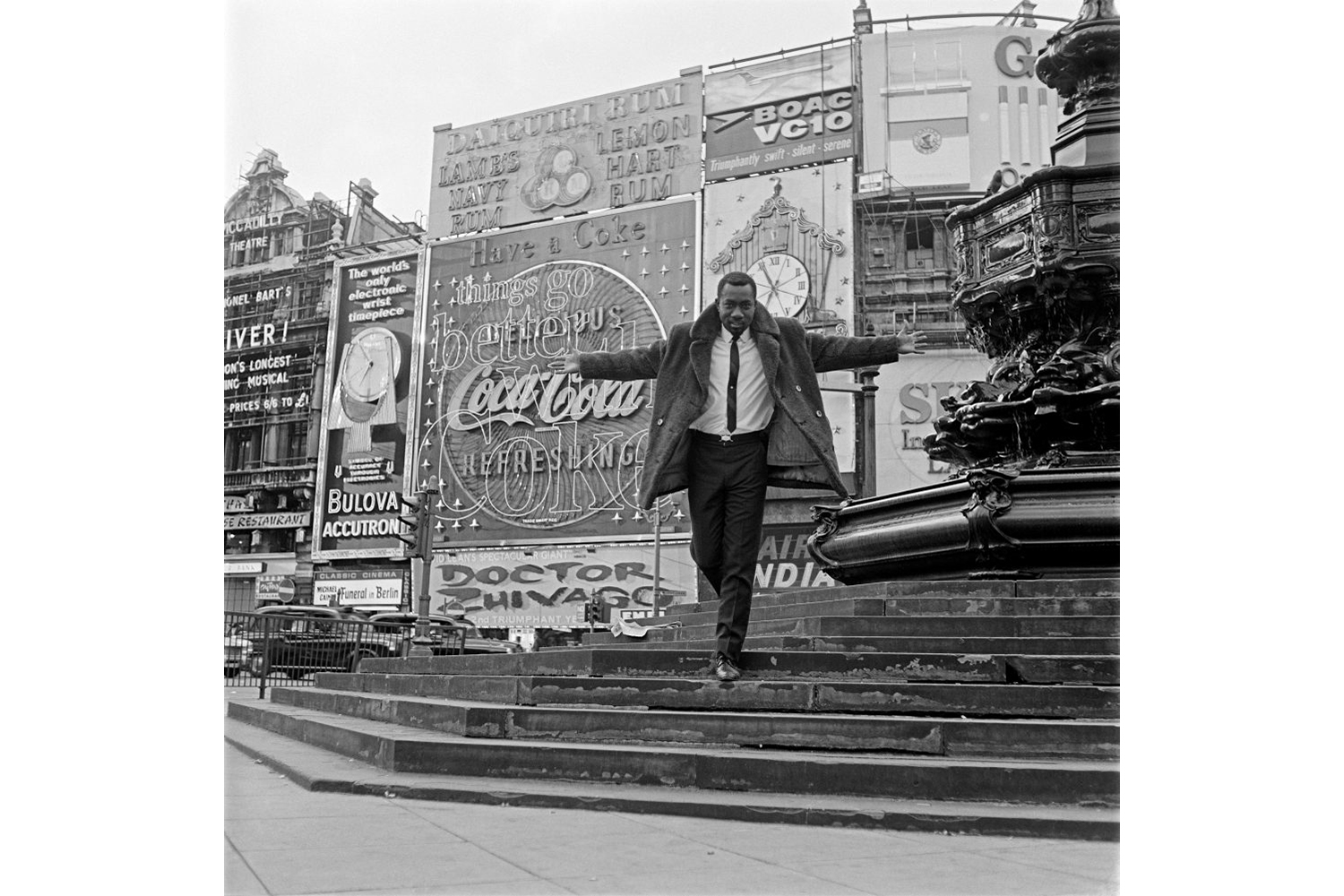

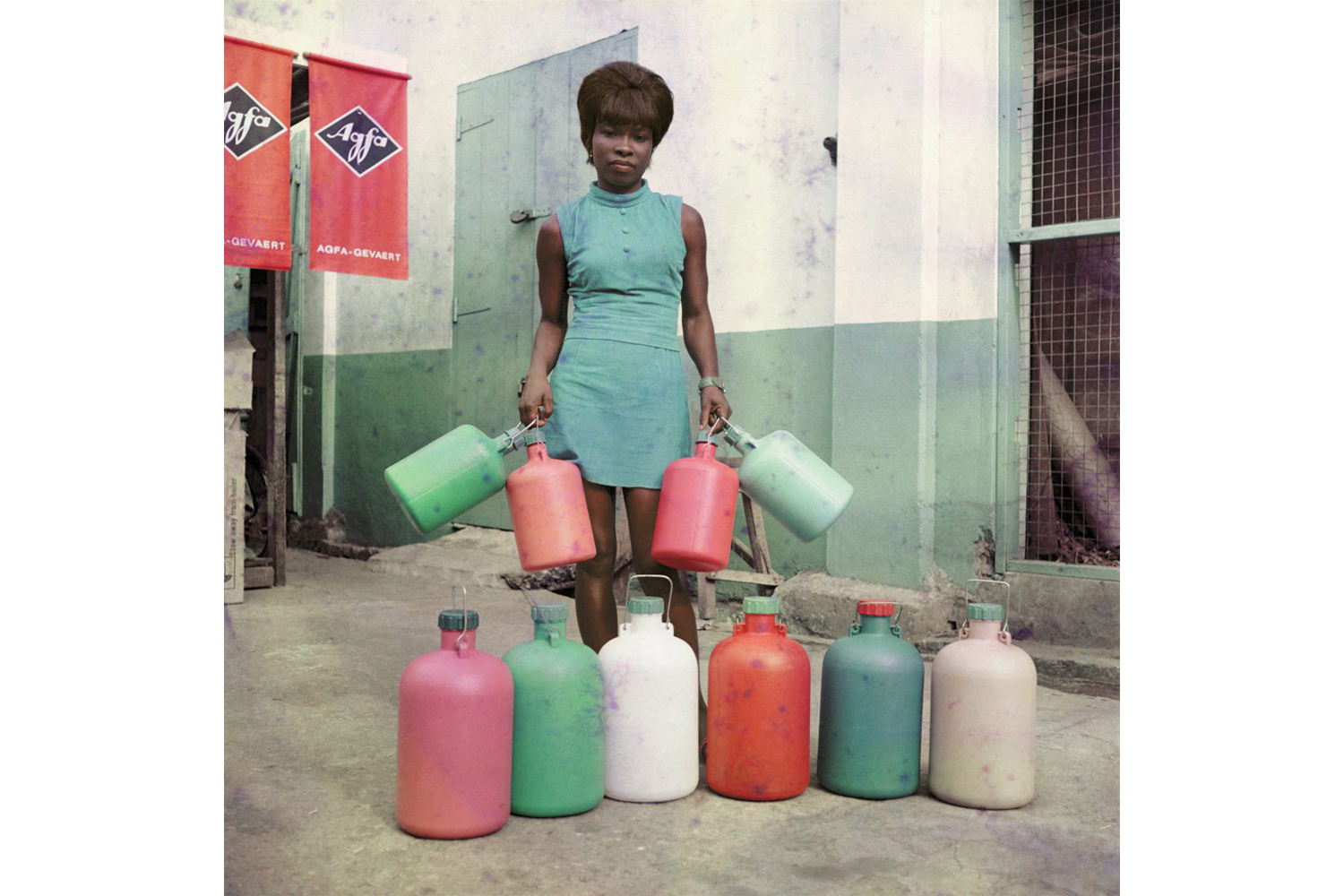

And like all portraits, these works are also negotiations between the individuals captured and Barnor’s own stage management: “I thought that if someone came in, I’d make them look younger. So, if I open a studio, what should I call it? Ever Young.” Mike Eghan joyously gliding down the steps at Piccadilly Circus is just one instance of Black diasporic experience that ranges between the mundane and the rapturous at a time of racist proclamations in Britain — “No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish” — and Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech of 1968. Renée Mussai, Senior Curator and Head of Curatorial, Archive and Research at Autograph ABP, London, sees analogies between Barnor’s cosmopolitan self-fashioning and his contemporary Frantz Fanon’s “ode to self-invention.”1 At times the works here follow Barnor’s travels; other instances (such as his return to Ghana in 1970 to establish the country’s first color-processing laboratory) suggest that travel followed work. The reciprocity of relationships between artist, sitter, location, and practice resonates with Fanon’s articulation of a diasporic subject that is “endlessly creating myself.”2

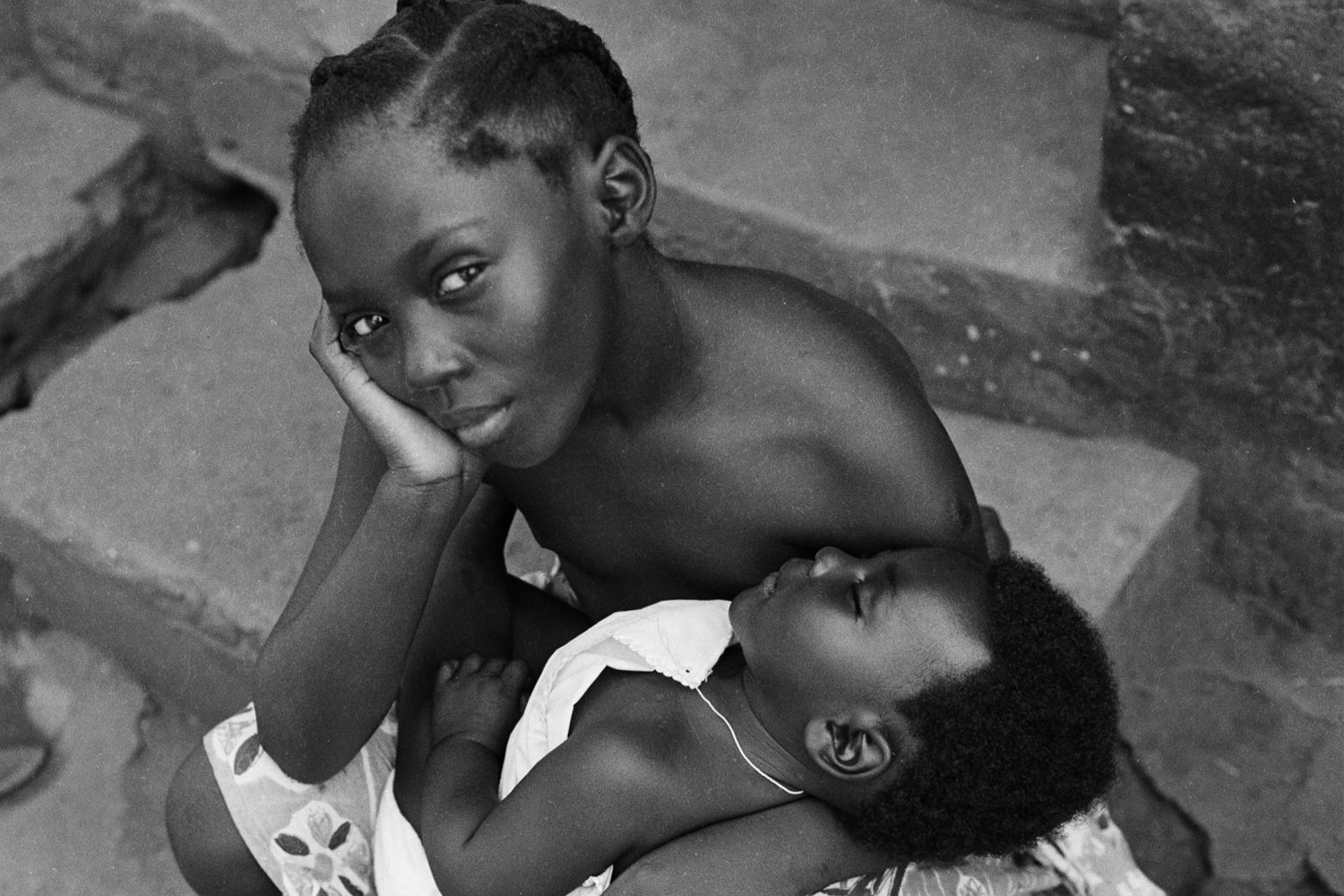

Family members, friends, strangers on the streets of Accra, London, and Kent are here elevated to a status that resists temporality. Yet these photographs also reverse the colonial model of center and periphery, whereby the metropolis is posited as a centrifuge of innovation and culture. In Barnor’s hands, action and, significantly, education and innovation occur on the margins, in both a global and suburban sense. At the Serpentine, institutional exploitation of his archive for political posturing is absent, perhaps in the way that only a retrospective could achieve. That it has taken so long, however, speaks volumes.