In Harlem Renaissance writer Richard Nugent’s 1926 story “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” the narrator remarks that it’s “funny how characters in books said the things one wanted to say.” Isaac Julien’s career-spanning survey at Tate Britain collects together his own cast of characters, many also plucked from the Harlem Renaissance, for himself to speak through. Pseudo-fictionalized, finding themselves caught between time zones, his films probe history to rub up against the present. In their speech and in their presence, his figures articulate a modernity of thought, a Black, queer consciousness that uses memory to enact a futurity that is rarely uttered in the museum.

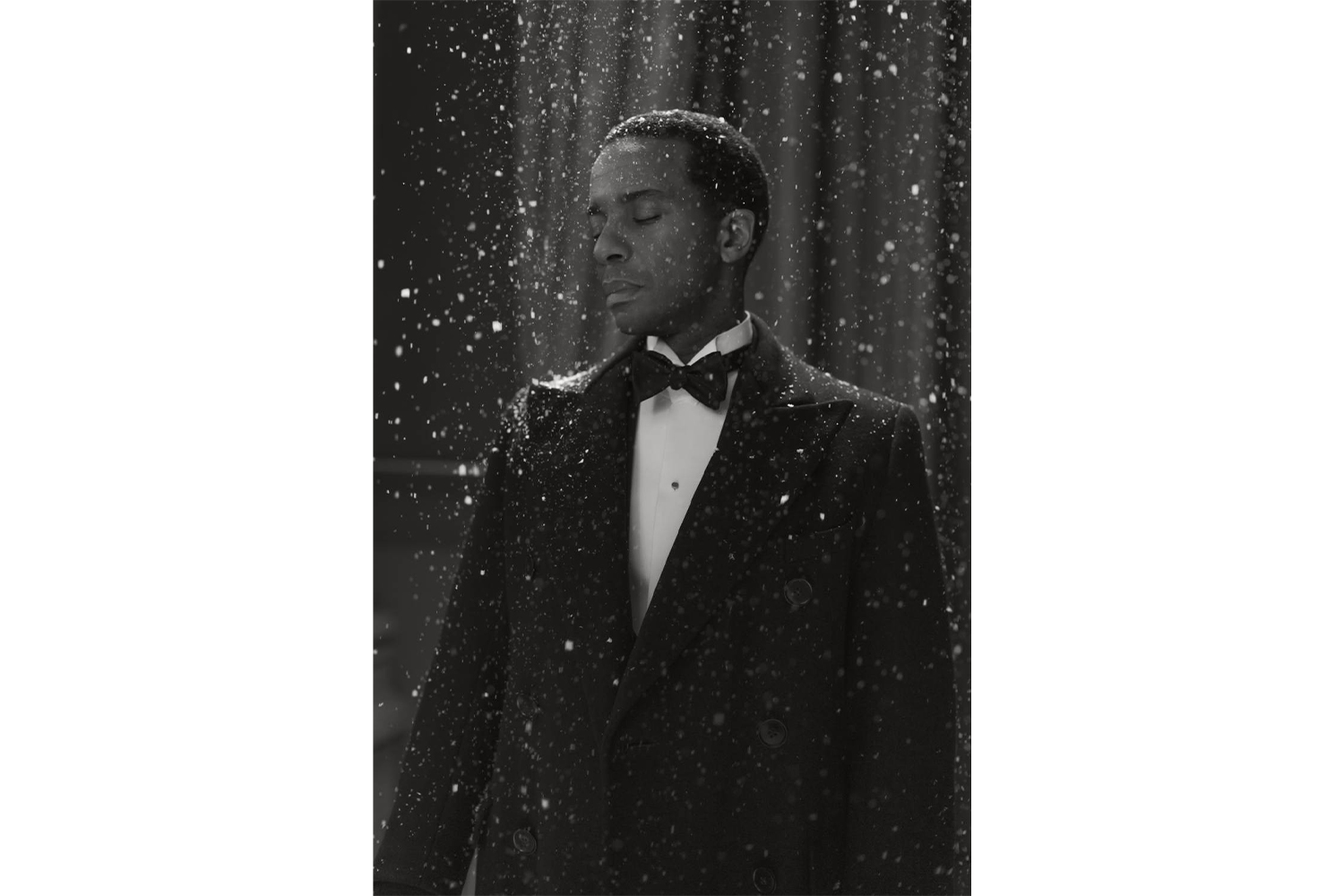

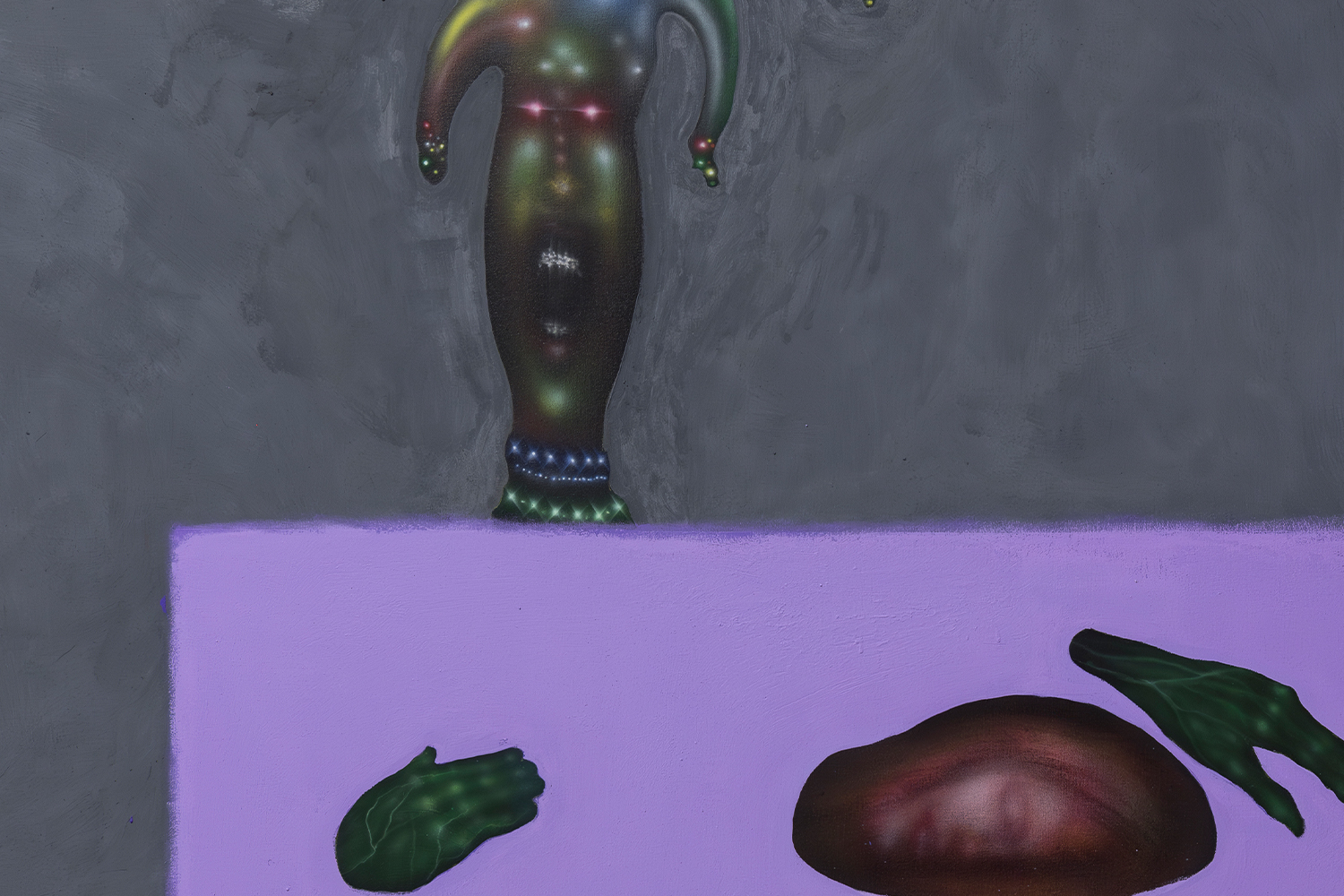

Throughout “What Freedom is to Me” (the title is taken from Nina Simone), which assembles eleven films from Julien’s four decades of work, the museum recurs as both a lush setting and a problem to be worked through. His characters repeatedly wrestle with the looting and plunder, the rewriting and erasure, of non-Western and non-male histories under the rubric of the institution. In his Turner Prize work from 2000, Vagabondia, a Black female conservator moves in a dream through the Sir John Soane’s Museum after dark like a thread through the eye of a needle. On two screens, her image is reflected, mirrored: the dichotomy of Julien needing to contend with the museum, and yet fantasizing about its distortion. He disfigures the museum further in his newest work, and spectacular entrance to the show, Once Again… (Statues Never Die) (2022), in which Harlem Renaissance philosopher Alain Locke interrogates Albert C. Barnes, collector of African artifacts and founder of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, where much of the film takes place. The five-channel film is mirrored in surrounding mylar walls, problematizing the viewer’s gaze, and this installation is punctuated with sculptures by Richmond Barthé and Matthew Angelo Harrison, each embedded in a thick, transparent casing that gives the feeling of submerged permanence, a drowning. In the film, Locke asks, “And what of the museums of which Europe is so proud?” — a question to which the shattering answer comes later: “All the museums in the world could never outweigh a lone spark of human empathy.” Locke (and Julien) dream of restitution, and of something beyond, conveyed by the work’s lasting image of Locke in crisp tuxedo amid falling snow. The eye takes a few seconds to realize that the snowfall is in reverse: an uprising that might, as per Locke’s hopes, return the diaspora to itself, and provide an “artistic freedom

as pure and unsullied as falling snow.” The Tate show intervenes curatorially to undo some of this traditional museum show hierarchy.

The films are presented non-chronologically, in an exhibition design by David Adjaye where each film fans off in its own room from a central lobby. One disappointment was the squeezing of four of his early 1980s films, produced as part of the Sankofa Film and Video Collective, into the echoey corridor outside the entrance to the show, so that the textural experimentation and biting critique of Britain in Territories (1985) are difficult to hear and feel. But inside, visitors can choose which film to view with the knowledge of how much time has elapsed so far, and thus are actors with agency in this richly textured cinemascape, moving horizontally through the exhibition in a way that echoes the panoramic experience of viewing Julien’s films. Within his sculptural, expanded cinema, films like the ten-channel Lessons of the Hour (2019), included here, are impossible to view with a single field of vision. In their length, complexity, and flourishing, his films expound on Christina Sharpe’s notions of “force and velocity and accumulation”; they build a new collectivity that, in its humming and movement, approaches the radical communion of Black life. “What Freedom is to Me” at times feels like a eulogy: for the permanence of the museum; for the spontaneity of the city; for queer life lost to AIDS in Looking for Langston (1989); for funding structures like the Federal Writers Project that enabled Richard Nugent and Langston Hughes to write; funding for Black film workshops like Sankofa from Channel 4; and the Greater London Council before it was axed by Margaret Thatcher. Julien’s fast and loose playing with time opens up this mourning to be a doorway onward, toward the joy and beauty and dancing of resistance, and freedom.