Heji Shin is going to accept everything and just be very positive. She is bored of provocation. The photographs that helped build her career and establish her image were often provocative: for “#lonelygirl,” her 2016 exhibition at Galerie Bernhard in Zurich, a monkey named Jeany replaced the artist in a series of self-portraits. One image of Jeany sucking on the end of a dildo, both eyes closed in reverent contemplation, landed her on the cover of Artforum. The show’s accompanying text explained that it was a survey of selfie tropes used by girls on Instagram back then: “to be rich, to be a whore, to be beautiful, to penetrate and visualize one’s anus. […] How do I represent ME?” There were lots of ass shots. It was a portrait of the artist as a monkey’s ass.

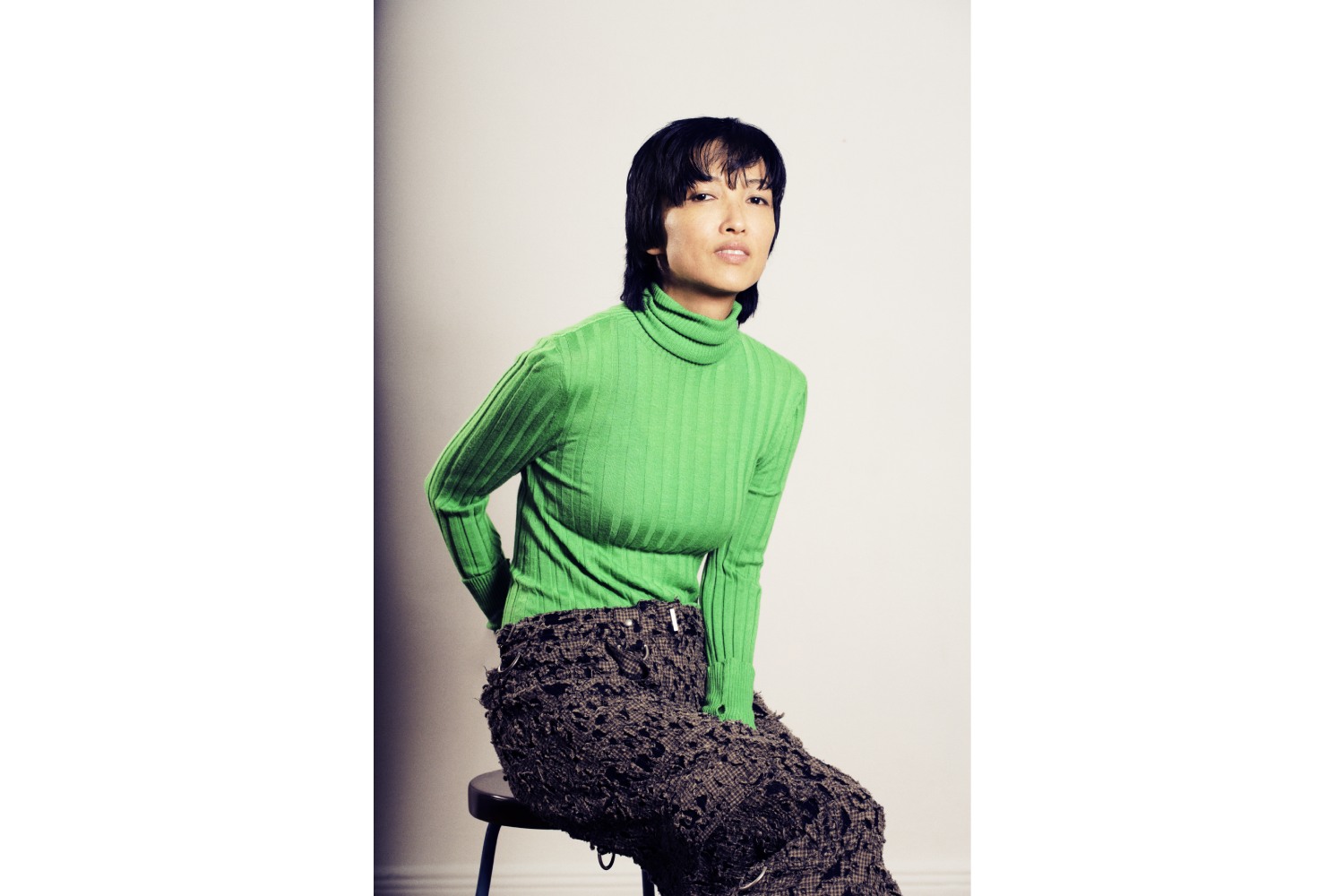

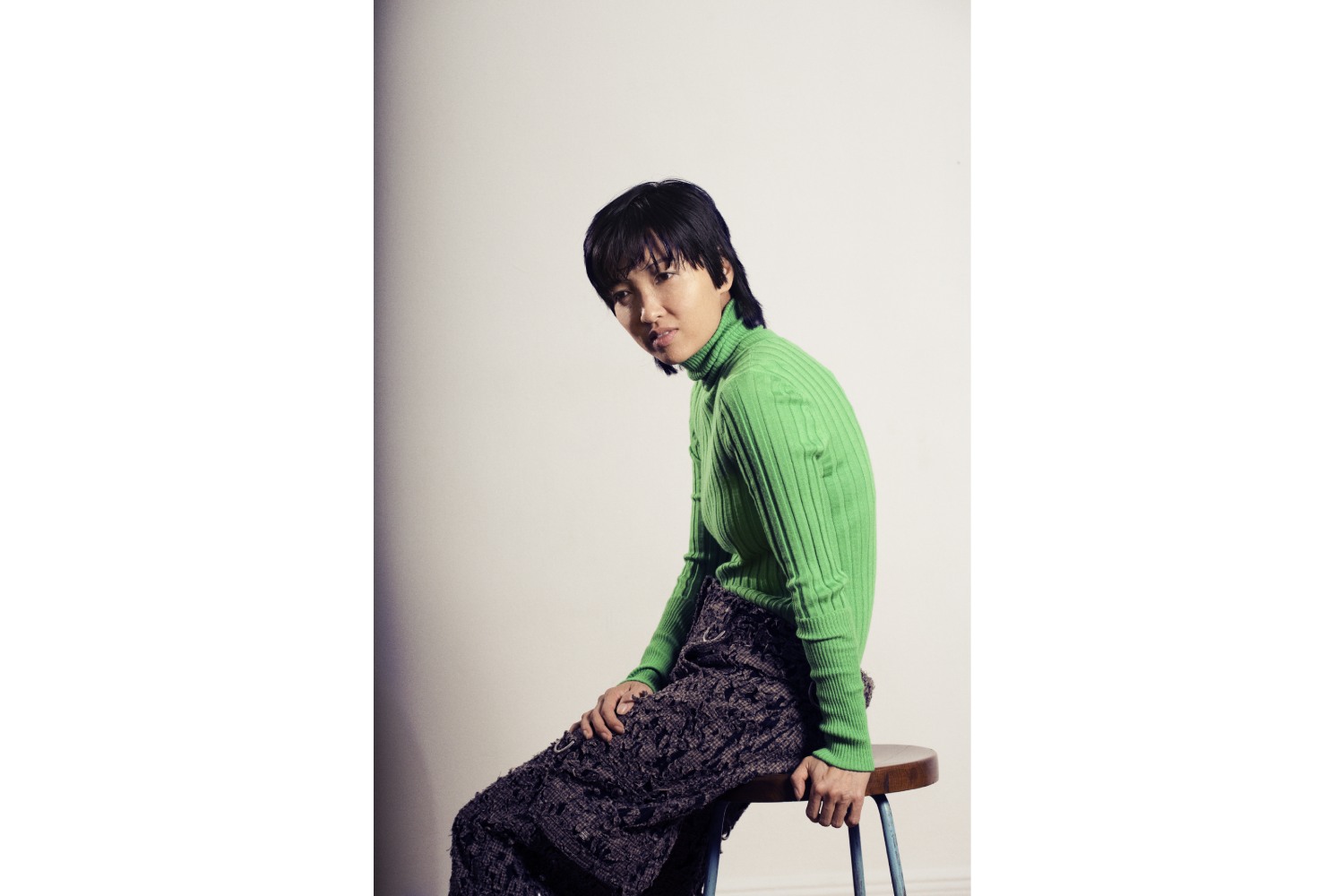

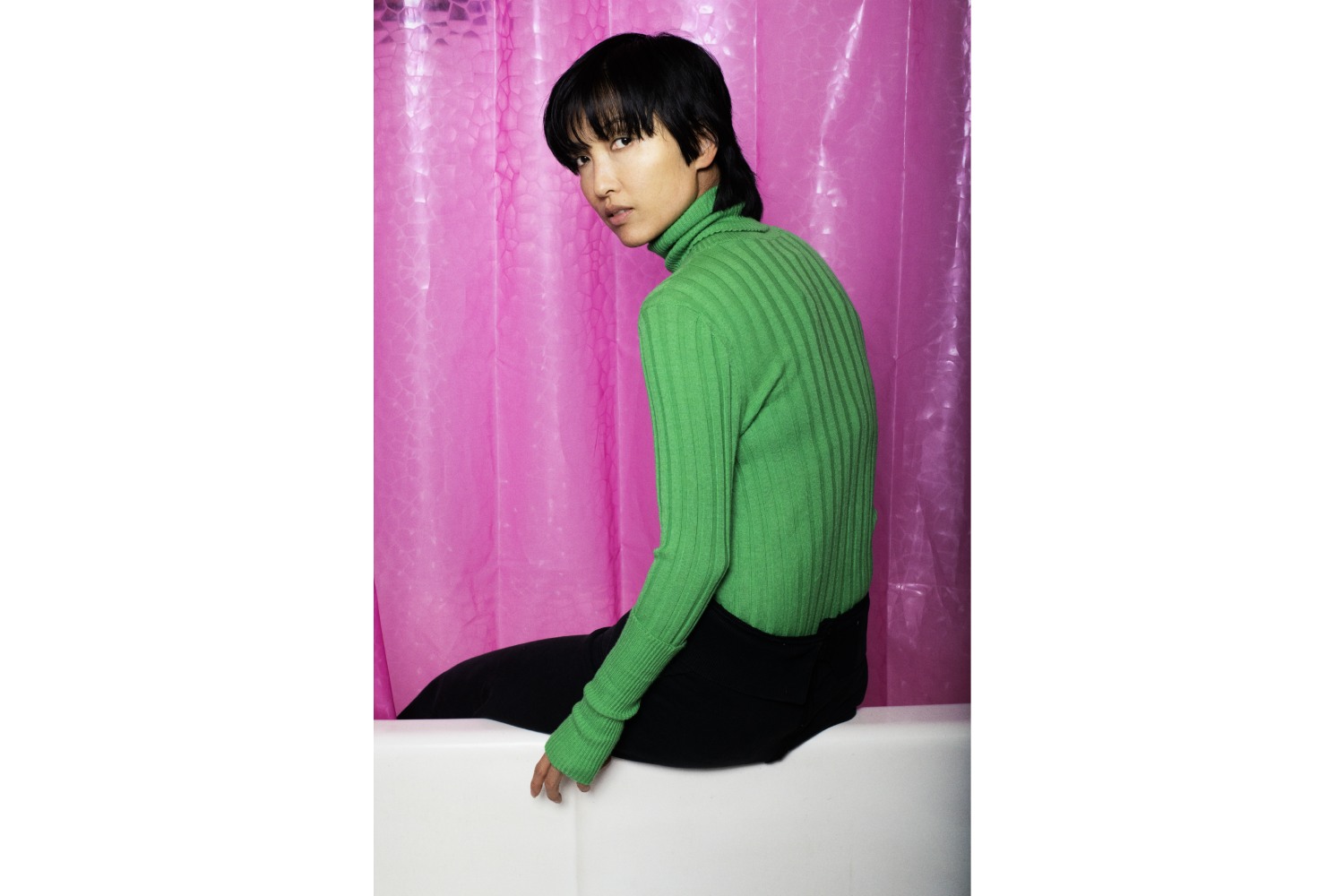

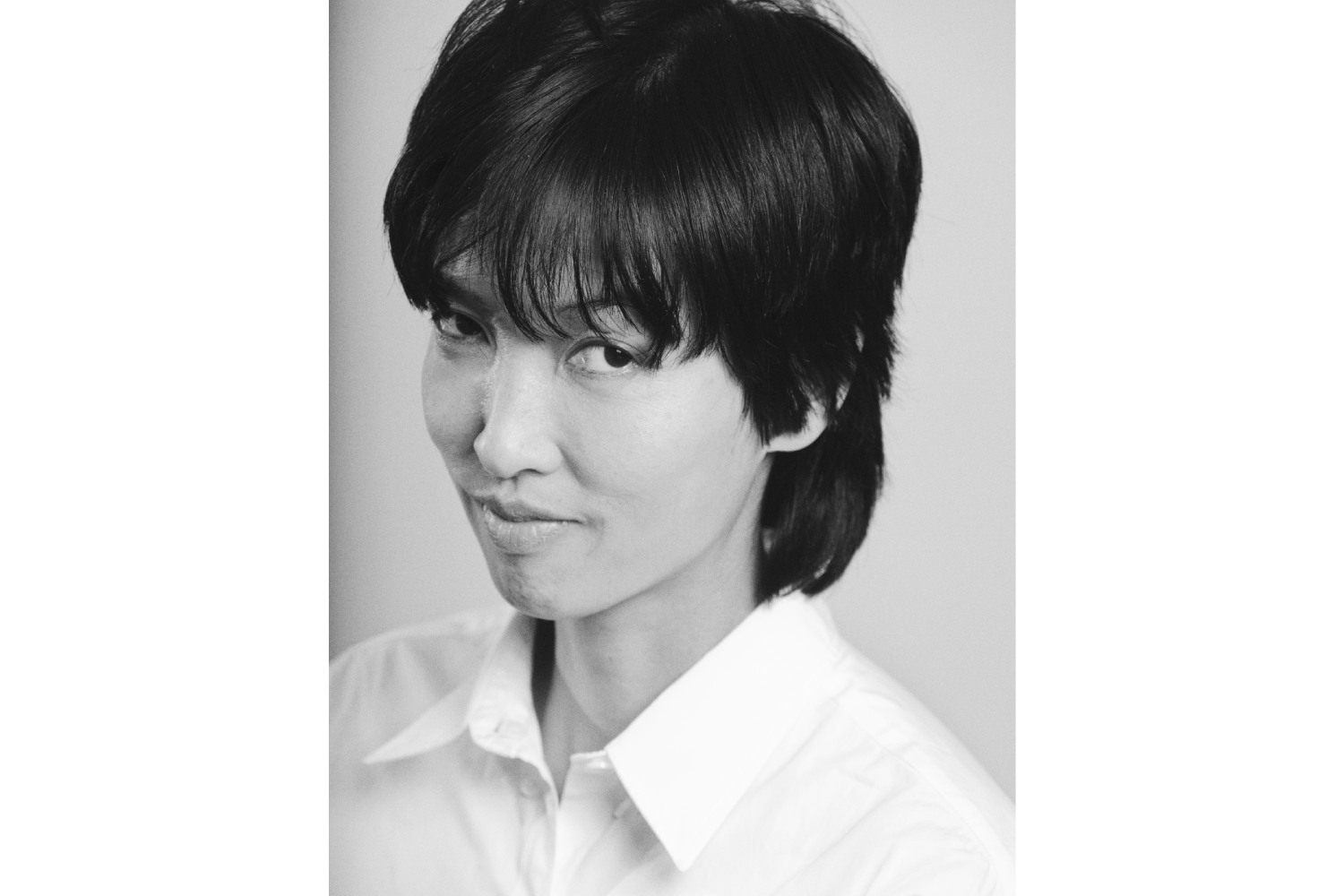

Her “Baby” pictures, also from 2016, captured them right as they emerged, gloopy, grumpy, blue-purple, bloody, and squashed from their mothers’ vaginas. Her spring 2017 campaign for New York fashion house Eckhaus Latta documented young couples having penetrative sex. Her “Men Photographing Men” exhibition at Reena Spaulings Fine Art in 2018 starred male porn stars dressed as NYPD cops fucking one another. Her portraits of Kanye West, shown at Kunsthalle Zurich in 2018, were criticized online because of Kanye’s friendship with Trump. Heji was born in Seoul in 1976, grew up in Hamburg, found a job taking portraits for an economics magazine in Berlin in the 2000s, and had her first breakthrough when she photographed Make Love (2011), a sex education book for German teenagers. She began to show her photographs in galleries, moved to New York City, began to shoot fashion as well, and has had exhibitions at Real Fine Arts, Reena Spaulings, Galerie Buchholz, and 52 Walker (David Zwirner’s Tribeca gallery). Her work has been included in the Athens and Whitney biennials, and she has shot for Givenchy, Tom Ford, Y-3, Purple, Vogue, and POP. Earlier this year, she was asked to take my picture for Arena HOMME +; she declined.

When she was selected for the 2019 Whitney Biennial, her “Babies” were hung in the main galleries, and her “Kanyes” (which she’d asked to have included) were hidden away in the basement, between the toilets and the cloakroom; the basement, she mentioned when I first interviewed her back then, is thought of traditionally as a space of psychological repression. She told me that an artist should have some meanness and aggression and shouldn’t worry about satisfying others: “You should actually do what people think is wrong. That’s what I’ve always thought. That’s what I like. I’ve never thought of trying to do what other people think that art is.” But now Heji has abandoned provocation.

“Because,” she says, “provocation has also become a very everyday experience when you just look around.” In 2023, provocation is all around and feels completely played out. Instead, she is trying out positivity and “total acceptance” of herself. This change didn’t come from an epiphany on the Upstate New York farm where she now lives, or from a hike in the mountains with her nature-loving husband Mathieu, or looking deep into a pig’s familiar eyes and seeing her own soul staring back at her, or reflecting on her own actions and the role an artist must play in these times. “But this term actually came from this Jeff Koons MasterClass [a video lesson on creativity] a lot of people watched, where he was talking about how a way to make art is accepting everything about yourself, who you are and what you like, and how that leads you to something that could be interesting,” she says.

Koons and Shin have much else in common: both have collaborated with fashion houses, both have made hardcore pornographic art and enjoyed provocation, and both make unusual portraits of themselves, of celebrities (Michael Jackson, Kanye, Kim Kardashian), of monkeys or great apes (Michael’s pet chimpanzee Bubbles), and of pigs (Koons has made some fantastic sculptures of pigs).

“Maybe I’ve been talking about positivity,” Shin continues, “because everybody is so obsessed with being negative and with weakness” — with this belief that we are helpless and that structures of power and material conditions have determined all of history and severely limit our capabilities in the present — “which is of course totally crazy. It’s a really deterministic and fatalistic view.”

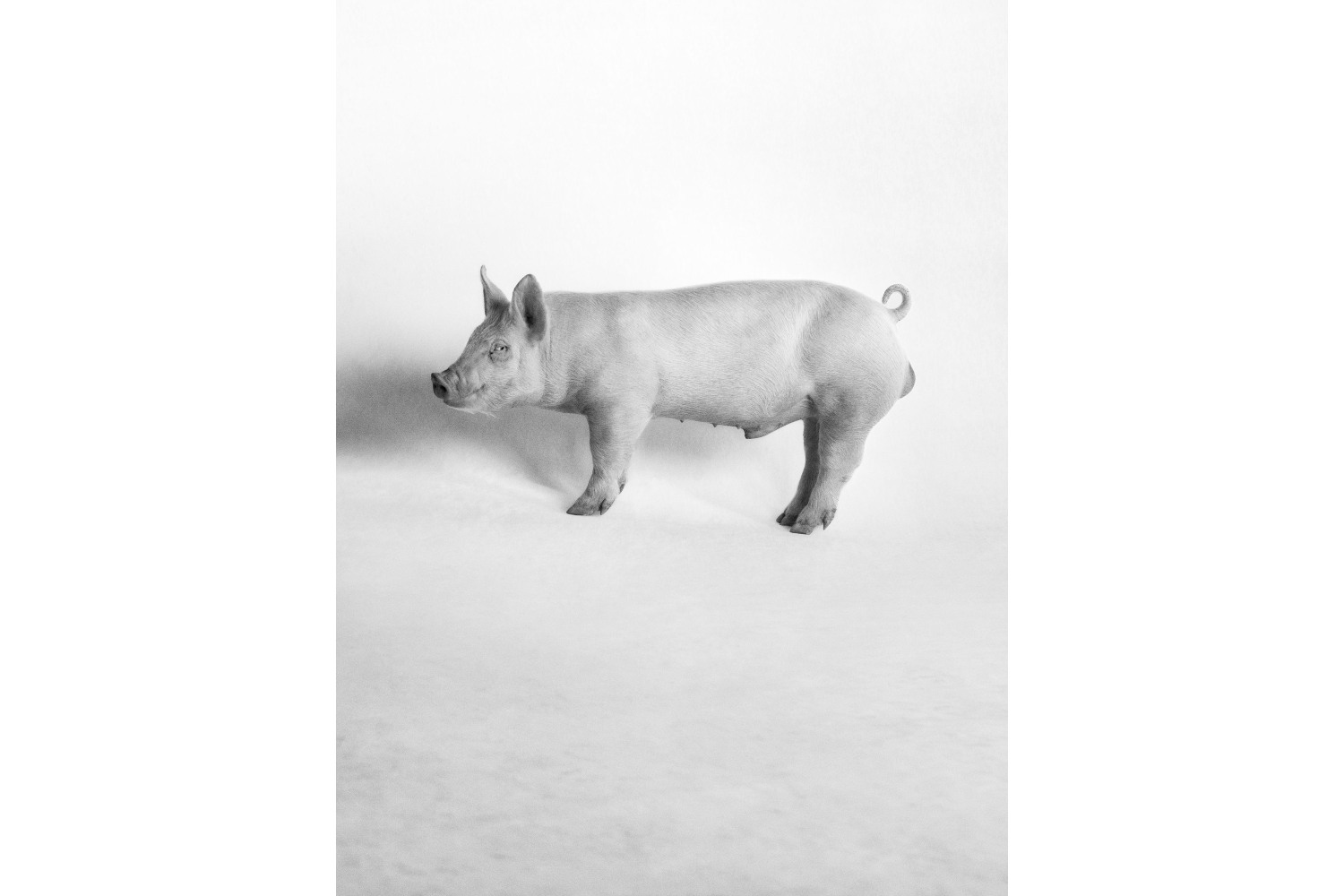

For her most recent show, “Big Nudes” at 52 Walker, she exhibited large fashion editorial-style images of piglets posing in a studio alongside prints of MRI scans of her own brain, another sort of self-portrait. In the center of the space, a three-dimensional multicolored image of Heji’s brain, in the form of a Pepper’s Ghost optical illusion, spins slowly around. She is interested in brains and how they can be manipulated: her choice of related readings for the 52 Walker library includes Edward Bernays’s Propaganda (1928), David Talbot’s The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government (2015), and Tom O’Neill and Dan Piepenbring’s Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties (2019).

“The things that I’ve done, they’re all propaganda,” Heji says. “All propaganda. An artist has to be aware that they always make that. It’s just your subconscious. Propaganda for what exactly? You don’t even know yourself sometimes, but you’re always a prisoner of your own unaware urges and desires.”

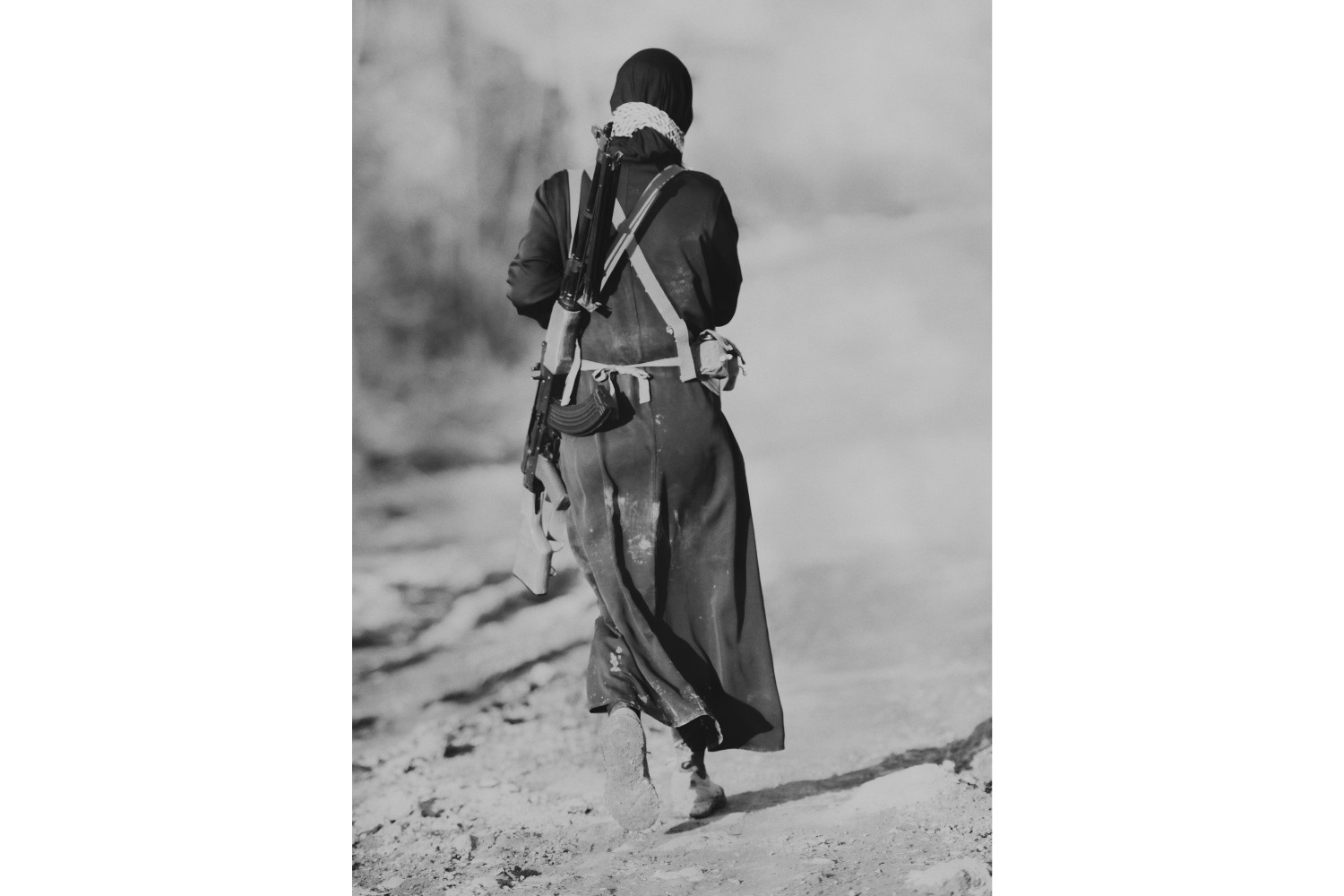

Her exhibitions often juxtapose different series without saying why. In Zurich, her “Kanyes” were shown alongside X-ray self portraits of Shin holding different dogs. At Le Consortium, Dijon, in 2021, she exhibited dramatic fake war photography of a LARP (live action role-play) of the Iraq War by pretend soldiers in Ukraine alongside more pictures of Jeany, originally shot for a Supreme campaign, taking apart and attempting to eat a disposable camera branded with the company’s logo. The monkey is a bad photographer, a malfunctioning image-maker devouring the means of recording reality. Everyone in the show is pretending to be something they’re not.

With her images of war reenactors in Ukraine, porn stars playing US policemen, and Kanye in happier times, Shin’s artworks can also seem to prophesize doom. She says it’s surprising how events have turned out, but that these rhymes may come from her attempts to channel the present: “When you do art, you’re very in touch with, not your rational side, but more that you feel an urge to do something. It’s the same with the pigs [shown alongside her brain]. Why? I cannot explain. Maybe it’s because I bought a farm.”

As soon as the pigs arrived in her studio, they were gamboling around, squealing, shitting everywhere uncontrollably. They could not be directed in any way, so Shin just fired repeatedly and took thousands of photos, then had to go back through everything later to find the decisive moments. For me, then, the medical images of the brain suggest Apollonian order, and the pigs, Dionysian chaos. According to Nietzsche, the highest art is a combination of these Apollonian and Dionysian drives. According to Camille Paglia’s Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson (1990), another of Shin’s selections for the library, everything great in Western civilization comes from the struggle between them; Shin has also shot Paglia’s portrait. Her photography, read through the prism of Sexual Personae, is Apollonian (masculine) in its clarity and rationality, with each series starting from a simple idea, but also Dionysian (feminine), which Paglia prefers to call “Chthonic,” in its wild, chaotic nature, unconstrained sexuality and fertility, and seductive aesthetics.

For her exhibition “Angel Energy” at Gaga & Reena Spaulings LA in 2019, Shin’s three series of images of women began as ideas reflecting the city’s themes of celebrity, pornography, superficiality, and hyperreality: first, photomontages depict CGI porn-star avatar “Jedy Vales,” who had recently been created by YouPorn, breastfeeding flesh-and-blood babies; the crowdsourced whore is reimagined as Virgin Mary. Second, polarized, spectral, degraded ghost-pop portrait-impressions of the Kardashian and Jenner women are made by peeling open Polaroid prints to reveal the chemical emulsion, photographing them again and manipulating their already-unreal colors in post; Kim, 2019, in green and yellow, looks like Warhol’s Mona Lisa drawn in piss-oxidized copper. Third, a fashion shoot featuring Kardashian lookalikes for The Face is treated with vintage Polaroid filters to give the look of the original subjects’ — the real celebrities’ — Instagram posts. (British sociologist Dick Hebdige, writing in 1988 about The Face in Hiding in the Light: On Images and Things, said the publication was “hyper-conformist: more commercial than the commercial, more banal than the banal,” and that it “flattened everything to the glossy world of the image, and presented its style as content.”) Lastly, to close the circle, the bizarro lookalike “Kim” is shown breastfeeding a baby doll.

These are pictures of a world where you can’t trust what you see. Reality is crumbling away, cheaply and tawdrily, and that crumbling can, at moments, appear very beautiful. They are fake images that represent our age very truthfully. Four years after they were made, as I’m writing this profile, Meta has just announced “Billie,” a multimillion-dollar AI-powered virtual being played by Kendall Jenner that looks and sounds exactly like her but isn’t really her; “Angel Energy” now seems like another cursed prophecy of an unsettling, ridiculous present.

In his introduction to Helmut Newton’s book Big Nudes (1982, from which Shin borrowed her most recent exhibition title), Karl Lagerfeld writes that there is nothing nostalgic about Newton’s photography. He would surely have admired the same quality in Shin’s. She’s never remaking the past and starts with ideas rather than huge mood boards of images to reference and copy. “Now that painting has gone up so many blind alleys,” Lagerfeld continues, “I feel that photography is the art that best expresses our age. I am afraid that painting is a finished form, like opera. Photography must be protected from becoming too ‘official.’ It must remain a living art.” Painting certainly is, in its more traditional forms, beginning to feel limited, dead, and extremely official. Photography, by contrast, continues to expand, and no artist exemplifies this better than Heji, with her X-rays, brain scans, Pepper’s Ghosts, collages of CGI porn stars, lookalike influencers seen through vintage, rephotographed Polaroid chemical reactions, crisis actors, and monkeys eating cameras. She experiments with technologies and collaborates with animals in ways that might be considered avant-garde (Moholy-Nagy and his photograms, Beuys and his coyote) — though she rejects this claim — and finds order, style, and consistency in the chaos that they bring.

Each of her images contains echoes of the others: a brain looks like Kendall’s peeled-off Polaroid face looks like an X-ray Heji with a pug looks like a virginal virtual porn star with an angel looks like a heavily retouched Givenchy campaign looks like a pig looks like two NYPD officers sodomizing one another looks like a baby emerging into the world. Bringing so many disparate methods together and combining them, her practice demonstrates how photography has changed from a tool of recording to one of construction, like painting or drawing. It used to be a way of documenting the world outside, but now, with scanning, copy-pasting, complex edits, and retouching becoming commonplace, it is just as often used to make new images.

Today, we are forever making images of ourselves and wish to see our identities and our lives reflected back at us throughout culture. Art and literature, social media, selfies, blogging, streaming, psychoanalysis, DNA ancestry services, and identity politics all strike at the central preoccupation of this narcissistic century: “Who am I? What makes me? Where does my authentic self reside? How do I represent ME?” Shin’s many portraits and self-portraits, her many ways of representing a twenty-first-century person, offer answers to these questions even while sometimes mocking them. Perhaps, as her last show suggests, the self is in here: in this glowing, rotating brain in a geometric casing.

She very often tries to take us inside of her subjects: tearing open Polaroids to see what’s under the surface of influencers that have made themselves into world-famous images; waiting to photograph babies pushed out; big cocks sliding in; X-raying two dogs fucking, showing us their skeletons as they’re inside of each other; imagining the brain as a “big nude” that reveals your naked self. While much recent contemporary art locates identity firmly in the realms of race, gender, and sexuality, and represents those on the surface, Shin’s brain-scans-as-propaganda suggest that we have to go deeper inside the person: that it’s here in the brain that the person you are, your preferences and beliefs — which you’re in total Koonsian acceptance of — reside. Your imagination, creativity, expression, freedom, strength, individual agency, and subconscious streams of desire and association are all to be found in the mind.

Heji stops mid-flow on the subject of propaganda and mind control: “Now I remember where the pigs came from! Of course, because the pigs relate to Charles Manson, because that’s what they painted on the wall: Death to Pigs.”